"I haven’t been transferred, I have been thrown out..."

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 40

No. 6,

June 2020

By Pranav Capila

And so it is exit, stage right, for Tana Tapi: the stalwart, the conservation legend, celebrated Divisional Forest Officer (DFO) of Pakke Tiger Reserve in Arunachal Pradesh. He is to leave the forests he rescued from the brink and nurtured over the course of a decade-and-a-half. He will be gone by the end of the month.

When Tapi came to Pakke in 2004 it was a tiger reserve only in name. In particular, poaching was rampant in most of its area. “I was driven quite mad in the beginning”, he told me in February 2016, the first time I visited Pakke. "There was a lot of poaching and virtually no infrastructure.”

Pakke’s frontline staff waged an all-out war against poachers in Tapi’s initial years as DFO. “We had to induce a fear psychosis in them,” he said; “they were too bold, too dominant.” At the same time, he began to expand the Forest Department's infrastructure in the reserve, building a jeepable road so his men could access more territory, establishing over 30 anti-poaching camps where there had been just one.

A conservation legend, Tana Tapi was a celebrated Divisional Forest Officer (DFO) of Pakke Tiger Reserve. He is to leave the forests he rescued from the brink and nurtured over the course of a decade-and-a-half. Photo courtesy: Nandini Velho.

His most important initiative though was to get local communities on board with him. “It was difficult at first because the Nyishi community – I am also a Nyishi – are traditional hunters. But the support of fringe dwellers was always going to be essential. So we tried to ensure that they benefited from whatever tourism there is, and from employment opportunities within the reserve. A conservation consciousness has gradually developed, especially among the youngsters,” he says.

That Tapi was able to keep the wheels of wildlife protection rolling in Pakke was something of a miracle. As of January this year he had just 10 permanent staff – three Range Forest Officers, two Deputy Rangers and five Forest Guards. His Special Tiger Protection Force (STPF) personnel were all contract workers. (STPF posts have not been regularised in Arunachal despite the National Tiger Conservation Authority having sanctioned them in 2009.) Wages for contract staff were routinely delayed by the state government. A requisition to purchase sorely-needed firearms for frontline staff had been languishing for seven years despite funds being available and despite representations to the Chief Secretary and Chief Minister.

"Wildlife has no value in our state," he lamented when I met him in January. "It is considered an 'unproductive cow'. Milk dene waala nahi hai. So nobody cares for it."

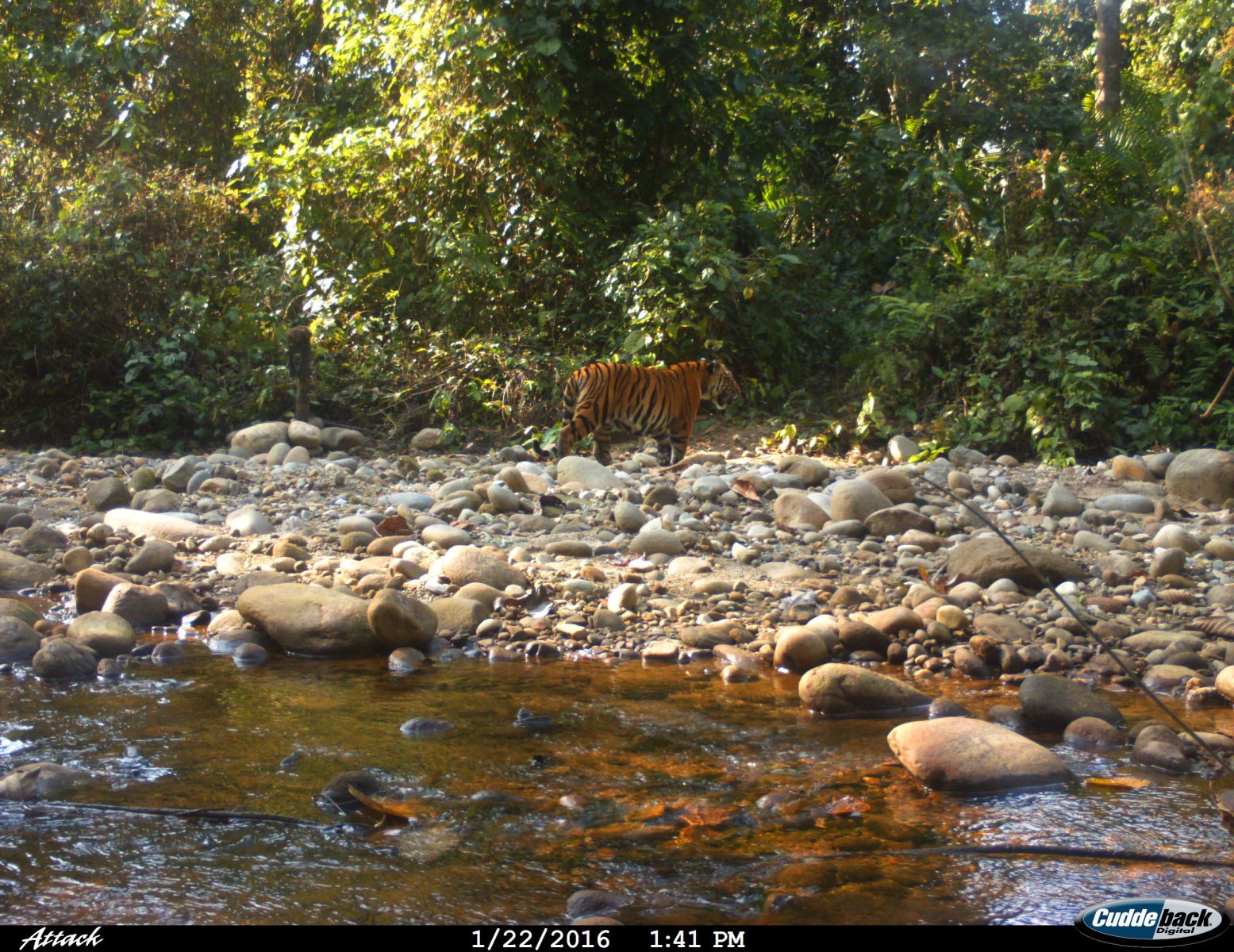

A camera trap image shows a tiger in the evergreen forests of Pakke Tiger Reserve.

Tapi had been a strenuous objector to the proposed 48.8 km. road that was to scythe through Pakke Tiger Reserve as part of the Arunachal Pradesh government's East-West Industrial Corridor project. Following sustained public outcry, Chief Minister Pema Khandu tweeted on June 6, 2020, that "environmental concerns had been taken into account", though a written clarification that Pakke has been spared is awaited.

Tapi, however, had clearly come to be seen at the highest levels as a roadblock. And so, exit, stage right.

But where do you transfer someone who has a postgraduate diploma in wildlife management, has been a hardcore wildlife conservationist for 18 years, has received 14 conservation awards from national and international organisations, and a state medal for meritorious service?

The Forest Department in its wisdom has decided that at the end of this month, Tana Tapi will hang up his field boots and leave his beloved wildlife posting for a metaphorical wilderness. His new posting is to a Territorial Division – Hawai division in Anjaw, the easternmost district in India.

.jpg)

Tana Tapi navigating a jeep through the lands he loved most. Photo courtesy: Pranav Capila.

Pakke’s loss will be Anjaw’s gain. But Tapi’s legacy will endure in the little slice of paradise that he loved, deeply and fearlessly. In the hunters that he inspired to become wildlife protectors, in the numerous people – frontline staff, researchers, youngsters from the local community – that he mentored, it will endure.

"They may remove me from Pakke but they cannot construct a road through the tiger reserve,” he asserts. “Many people, particularly young people in the community, are against it. The government should know that people do care about these things."

Thank You, Tana Tapi

Thank You, Tana Tapi

By Nandini Velho

“You can take Tana Tapi out of Pakke, but not Pakke out of Tana Tapi”, that’s the best that Team Pakke could string together when they heard the news.

For me personally, it’s very difficult to describe Tana Tapi. I’ve been searching for notes about him that I may have stored and forgotten somewhere on my computer. My search queries are: life.doc, pakke.doc, TT.doc. Perhaps he is the protagonist of my unwritten book. Someday…

There is much to be said about being mentored, supported and led by one of the most hands-on field officers in the country. He was the reason for and core of our getting together, staying together and working together. In the process, he took a little known tiger reserve in Arunachal Pradesh and sparked popular imagination and hope across the country. Have we had differences along the way? Plenty. Yet somehow that was our strength.

The most inspiring thing about him is his courage to stand up to power. He is a man of few words yet this is an unflinching aspect of his personality that is now his legacy. His yes is a ‘

hoga’ but more importantly, his no is a firm ‘

nahi hoga.’

A few years ago in the somewhat degraded Dezzling elephant corridor that connects Pakke Tiger Reserve and Eaglenest Wildlife Sanctuary, there was a plan to house the Indo-Tibetan Border Police Force. This would disrupt forest connectivity, but there was pressure to see it through from all quarters, including political. The buck simply and stoically stopped at Tana Tapi’s ‘

nahi hoga.’ On the matter of the Pappu Hydel Project even his fiercest opponents were caught hiding their smiles. His opening statement at the last meeting was to remind the audience that he said no to this project when the community hall was brand new. He said that his response was the same through all the meetings that had happened since, and would remain the same till the hall falls down.

Having him by my side has given me a distilled clarity and strength in practising conservation. A field that is otherwise thought to be a losing battle. I called him most recently about whether or not I should write an article on the irresponsible manner in which forest and wildlife clearances are being accorded in India. His one-line query to the source of my confusion was whether I was deliberately planning to write something that was not factual or true? If I was writing the truth, I had no reason to worry. And so, I had my answer and my article ready.

I’ve been trying to make sense about what moving on means, personally and professionally. So far all that I know is that moving on does not mean letting go. It means forming new teams and strengthening old bonds. Tana Tapi lit a flame that sparked a fire in many of us. Unfortunately, the same fire scalds us, now that he is leaving.

We will bid him adieu with grace, but as we prepare to tackle future threats to Pakke, one question will remain on everybody’s lips: What would Tana Tapi do?

Pranav Capila is an editor and writer who tells stories about wildlife, wild spaces, and unsung heroes on the frontlines of conservation. Nandini Velho is an independent researcher and conservation scientist. She won a Sanctuary Wildlife Service Award in 2015.

.jpg)