Bear Necessities

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 38

No. 2,

February 2018

By Aniruddha Dhamorikar

It is hard to tell if it is the same river you cross after every hill you descend. The jungle is new at every turn, and I might as well have crossed one-too-many. We were in the hills of Seoni, close to the Pench Tiger Reserve, the land Kipling adopted in The Jungle Book (1894-95), the land of many hills and rivers, and stories. One late afternoon, I halted at a large rock jutting out from a dry river, looking at tilting ribbons of light cast rippling shadows on the dusty bedrock. It was too early in the year for the rivers to turn into puddles.

At another time, along one such river, one late afternoon, the ‘Jungle People’ were gathering by the Peace Rock. The rains had failed, rivers shrunk, and trees and vines shrivelled and withered. “If I were alone,” mumbled Baloo, “I would change my hunting-grounds now, before the others began to think.” As a kid, Kipling’s narration of how fear came always made my hair stand on end. “And yet – hunting among strangers ends in fighting; and they might hurt the Man-cub. We must wait and see how the Mohwa blooms,” Baloo added.

Historically, the sloth bear has been ambiguously potrayed throughout literature and even today is poorly understood. Courtesy: Pavan Annigeri

A Living Relic

Earlier than Kipling, James Forsyth in The Highlands of Central India (1872) writes that sloth bears “appear to lose their natural apprehensions of danger in some degree during the Mohwa season.”

Dunbar Brander in Wild Animals in Central India (1927) speaks of them as being “the most intelligent animal in the jungle, the primates excepted,” adding that “The time of plenty is when the fleshy calyx of the Mohwa tree is continually dropping, and it is an extraordinary sight to see the bears competing with each other so as to be first on the spot.”

Thus far, in my journeys through the Kanha-Pench landscape, sloth bears have always eluded me. A decade ago, in another landscape, on another bend on the hill, I had come face-to-face with an indolent bear loitering down a shallow dell. Needless to say, I was off in the opposite direction. To each his own fear, Baloo would have said. Forsyth describes sloth bears as “generally very harmless until attacked” adding darkly that “sometimes, however, a bear will attack savagely without provocation – generally, when they are come upon suddenly, and their road of escape is cut off”. Brander opined that, “a she-bear with cubs is a most dangerous animal to disturb” and “it is a jungle axiom that one never can say what a bear will do”.

Be that as it may, humans and sloth bears have coexisted more-or-less effortlessly for centuries.

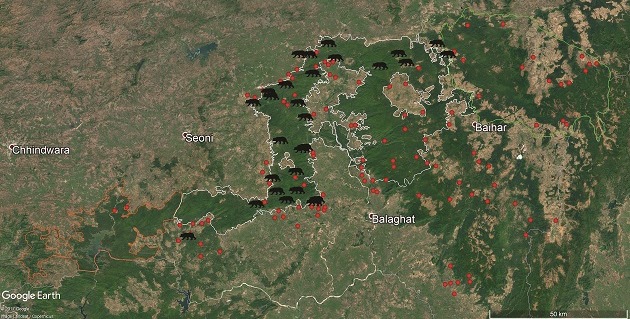

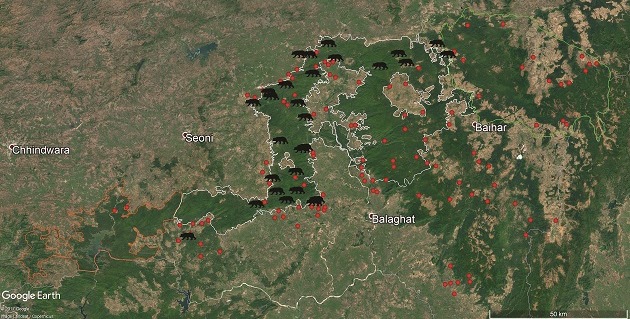

The Kanha-Pench landscape

This vast stretch of forested area that lies between the two iconic tiger reserves has had several sloth bear attacks, second only to those by wild pig – and first in terms of causing fatalities. We wanted to know why.

Early writings suggest the conflict is centuries old, but we have few details apart from the association between sloth bears and mahua flowers. By all accounts bears do not attack humans as prey, but they do cause grievous injuries. In the Kanha-Pench landscape such conflicts have deep conservation and social dimensions.

A mother sloth bear and her adolescent cubs momentarily pause before scurrying across the teak-dominated forests of Madhya Pradesh's Pench Tiger Reserve. Courtesy: Aniruddha Dhamorikar

Ground-realities

In March 2016, when the mahua Madhuca indica is in full blossom, we set out in search of one among 120 villages that dots this landscape. At the end of a long winding road through the Maikal hills, we were greeted by elders and children of Chikhlabaddi, a small settlement of about 10 households surrounded by a deciduous forest where at least five persons had crossed paths with sloth bears. One of the boys led us to meet his father, a victim of the encounter.

Bearing scars that he did not hesitate to hide, he animatedly narrated the events that transpired. Returning from his usual mahua collection outing, one day he suddenly chanced upon a bear at close-quarters. As his basket of flowers tumbled to the ground, the bear attacked with tooth and claw, wounding his legs and hands as he shielded his face and stomach from the bear’s wrath. The bear vanished by the time rescuers arrived. This wasn’t his first encounter with a sloth bear. It was a coincidence to be in the same place as the animal, he told us. In another part of the landscape, we met a girl who was attacked by a bear one late monsoon evening when she went to relieve herself at the edge of the forest. She heard some movement, but before she could react the bear charged at her from the undergrowth. She was also wounded on her hands and legs, and the bear retreated before help arrived. In another incident, three women were attacked in different parts of the landscape on the same day while collecting tendu leaves Diospyros melanoxylon – used primarily to make bidi – in the month of May. In all instances bears and humans were equally startled. In another case, a man on a cycle stumbled upon a bear feeding on ber Ziziphus mauritiana on the road. The bear charged, but vented its anger on the bicycle leaving the man unhurt.

As we interviewed several other persons, we noticed a curious pattern.

There was no doubt that most incidents occurred in forests or along forest edges, as they generally do in case of wild animal confrontations. In case of sloth bears, temporal variation played a major role: they differed with the time of the day as they did with the month of the year. Most incidences took place between 6 in the morning and 12 in the noon, largely between 8 and 10 a.m., and most were recorded during summer, followed by monsoon and winter. Incidences were greater in summer followed by the monsoon and then winter.

The weather was turning from the pall of a passing winter to the pale of the sun-bleached summer. More than half of the villages were empty by May, and we sought them at crossroads in the jungles where most people engaged in the tendu patta collection. I distinctly remember meeting an elderly gentleman, a bear-attack victim, deep inside the jungle engaged in building a bridge over a river that would connect his village to the nearest town. With a razor in one hand, he peered into his handheld mirror, shaving as he recounted his encounter. A small river curved gently in the forest behind him, and a dark blemish atop a stooping tree caught my attention. In its entirety, it was a honeycomb looming in the upper canopy of a tall arjun Terminalia arjuna, its trunk bearing faded scars of claw-marks. Pointing it out to our friend, he seemed little amused, calling the scars old, while his tale of how he received his during tendu collection in the same forest overpowered the resounding calls of the Brown-headed Barbet and the Common Hawk Cuckoo – sounds that likely resembled the ones the day the bear struck him.

A sloth bear cub attempts to scale a tree. Sloth bear cubs stay with their mothers for up to 24 - 36 months. Courtesy: Rohit Bhoraskar

The root cause of interactions

By the time Schaller wrote the remarkable The Deer and the Tiger (1967), sloth bears were already uncommon in Kanha. Forty years earlier, Brander had blamed this population decline on sport hunting. In the 70-odd kilometres we walked, recording signs left behind by loitering bears, my colleagues sighted it only once. Most of our respondents, too, said that it is rare to come across a bear, and for most, it was their first time to see one. Was it more than mere chance that added over 25 cases – and as many as 40 – a year?

Looking at human-sloth bear interaction from a social dimension made our understanding of conflict more coherent. Agriculture was largely for subsistence here, and was supplemented by collection of non-timber forest produce (NTFP) such as mahua flowers, tendu leaves, wild mushrooms, maulain leaves Bauhinia vahlii, chhind leaves Phoenix acaulis, and charfruits Buchanania lanzan, each harvested at a particular time of the year. With the addition of firewood for cooking and grazing of livestock, virtually every family was required to venture into forests. The months of peak sloth bear encounters coincided with the activity in forests. Mahua is in full blossom during March. In May, over 12 lakh people venture deep into forests to harvest tendu leaves across Madhya Pradesh. During July and August, men harvest wild mushrooms, a vital nutritional supplement for many communities. Most of these attacks have taken place during daylight, between 8 and 10 a.m., when people were most likely to venture out in large numbers. The attacks during winter occurred when people were engaged in collecting firewood and when they went farther in the forests to graze livestock. Attacks while the victims were engaged in open defecation and while travelling usually took place throughout the year, especially at dusk or dawn when bears are typically returning to their roosts or are in search of food.

Sloth bears are animals of habit. They frequent the same area periodically to feed and then retreat to the same roosting site. As they go about their daily business, they leave behind evidence of their presence. They scratch the barks of trees to mark territory, or to reach honeycombs. They open termite mounds and dig the ground for tubers, and their scats are distinctive of carnivores. Following in their footsteps, we tried to find whether there was also an ecological dimension to their interaction with humans. Specifically, we considered the availability of tree species with edible fruits or flowers and termite mounds – the major components of a bear’s diet – for their survival, and about anthropogenic pressures that degraded their habitat.

.jpg)

With increasingfragmentation and degradation of sloth bear habitat, there has been a spike in human-bear encounters that more often result in tense conflicts. Courtesy: Rahul Kuchankar

The Kanha-Pench landscape is richly endowed with natural diversity. Over twenty-five per cent of trees we recorded bear fruits and flowers relished by bears. Only a fraction of these are harvested, but other forest resources, such as firewood and fodder for livestock, are intensely relied on. From foot-trails to tar-roads, these jungles are a meshwork of human footprints. In addition to the necessary reliance on forest products, a rapid spurt in developmental activities is accelerating landscape fragmentation. Here, the density of edible trees is lower than the non-edible species, possibly compelling the bear to travel farther to feed. In addition, we found a subtle but noteworthy change in the next generation of trees; the saplings showed a shift in their composition from a mixed potpourri to single-species dominance, with the saplings of edible species showing significantly lower numbers than saplings of trees such as teak, a trend that perhaps foretells an altering ecosystem accelerated by anthropogenic factors.

Reconciling two facets

Through the ages, the sloth bear has been portrayed differently. In central India, Forsyth portrayed it through the eyes of a hunter, Kipling as an endearing animal with a deep knowledge of the jungle, and Brander as an ancient animal evolved to survive in the hot and dry central Indian hills. In addition to their ecology, recent studies have also focused on their interactions with people. This variation in its portrayal is a result of the differing contexts of perceptions – from hunter to conservationist, demographics – from low density to high density human population, and ecology – from the vast stretches of forests to smaller fragments. All add profoundly to our understanding of this unique species.

In retrospect, one can say that literature on wildlife has always followed the compassion of the observer, whether hunter or naturalist, providing us a small glimpse of the wildlife of a bygone era. Brander divided this into three epochs. He identified tales of game hunting in ancient history as the first, the second showcased writings of hunters like Forsyth. And as Jim Corbett exchanged his rifle for a camera in the north, Brander emphasised on the ecology of central India. This third epoch subtly marked the beginning of ecological literature in India.

What intrigued me is Brander’s opinion on changing ecological conditions, and his observations made ninety years ago are as relevant today as they were then– “the animals were not only hunted but found under conditions which no longer exist, and one would now look in vain for tiger or bear in country which in those days provided the regular hot weather beats of the most famous shikaris”.

We are well past Brander’s third epoch today. The landscapes have changed, as have the interactions between humans and wild animals. If I were to extend Brander’s school of thought, I would call the post-independence era the fourth epoch, when, armed with pen and paper, India carved Protected Areas and rehabilitated wildlife – of which the sloth bear, once captured and tamed as ‘dancing bears’, were successfully rescued and rehabilitated, and is one of the success stories of conservation.

Human-wildlife conflict, however, is a conservation concern that defies the boundaries of Protected Areas: in Madhya Pradesh, conflict with sloth bears has caused the highest number of human deaths compared to other large mammals – a majority taking place outside of protected areas. At the same time, bear poaching is alarmingly high – and grossly under-reported because most cases take place in the unmonitored recesses of our jungles.

In other words, for a species like the sloth bear, we must think beyond Protected Areas to usher in a fifth epoch: one of reconciliation between humans and wildlife. Central India is the largest contiguous stronghold for this species’ survival, but it is rapidly being fragmented. Cutting bears off from their feeding and denning areas will affect their populations and intensify conflicts as habitats shrink and interactions with people rise. This will mark the tipping point of the people’s tolerance, without which coexistence is unfathomable. If this isn’t alarming enough, within three decades, the IUCN warns, India – home to the largest population of sloth bears – will have a 30 per cent fall in sloth bear populations as a result of habitat fragmentation, and unscrupulous hunting and poaching for its bile, while the human population shoots over 30 per cent in the same period.

Standing atop that boulder, I pictured Baloo sitting with Mowgli, and his words of caution that I took for a children’s tale became clear: “hunting among strangers…” symbolises competition over a shared resource, which often, “…ends in fighting” – symbolising the conflict. “We must wait and see how the mohwa blooms” points to whether or not we will allow the inhabitants of the forests, the wildlife, to coexist alongside us.

What I portray here is a picture of a sloth bear that is not different than Baloo – a wild Baloo – the last to be free to come and go as he pleases; who relishes nuts and roots and honey; whose necessities are indeed bare; who does not wish to cross paths with humans. Who – and I say this picturing a dark cloud looming over his brooding face – wishes humans would be a little more considerate with his jungle. Equipped with the right intentions and actions — both social and ecological – an era of coexistence is comprehensible.

Most sudden confrontations can be avoided. Engaging communities in bringing about small behavioural changes, in addition to integrating social interventions through government and private channels, can reduce human-sloth bear interactions.

The new epoch has already begun in landscapes across India, it is time central India led with its beloved Baloo, the bear of central India who taught Mowgli – and indeed every child and adult alike – the laws of the jungle.

MAP NOT TO SCALE

MAP NOT TO SCALE

The Sloth Bear in India

- Sloth Bear Melursus ursinus is the most wide-ranging of the four species of bears endemic to the Indian subcontinent. It is the only bear having myrmecophagous (ant-eating) adaptations.

- It is protected under Schedule I of the Wildlife (Protection) Act of 1972 and is listed in Appendix I of CITES. Declared Vulnerable by the IUCN, its population is on a decreasing trend. Studies have put their population range between 10,000 to 20,000 individuals. However, no robust figures exist, making it difficult to monitor their population dynamics.

- The National Bear Conservation and Welfare Action Plan for India was launched in 2012, highlighting the vulnerability of sloth bears in India to habitat fragmentation, poaching, and the increasing incidences of human-bear interactions leading to resentment and retaliatory killings.

- The Kanha-Pench landscape lies in the most forested districts of Madhya Pradesh, with Balaghat, Mandla, and Seoni, ranking first, fourth, and fifth, respectively, in terms of forest cover, making it one of the most promising contiguous conservation landscapes for sloth bears.

- In the Kanha-Pench landscape, most of the human-bear interactions took place when people ventured into forests to collect non-timber forest produce (42 per cent), firewood (15 per cent), and while grazing livestock (13 per cent).

Aniruddha is interested in exploring the relationship between culture and nature, how they interact and affect one another, and what history has to teach us in moving towards an ecologically conscious society. The study of the dynamics of human-sloth bear conflict in the Kanha-Pench corridor was supported by The Corbett Foundation, DeFries-Bajpai Foundation, and the Madhya Pradesh Forest Department.

Author: Aniruddha Dhamorikar

.jpg)

MAP NOT TO SCALE

MAP NOT TO SCALE