Cashew Feni and Forest Tales

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 37

No. 2,

February 2017

By Anushka Rege

Cashew feni, an alcoholic drink brewed from the cashew bonda (as its fruit is locally called) is popular in Konkani culture. Like the biological and cultural diversity of the Konkan, this drink too blends well with a variety of other drinks, yet never loses its own distinct flavour. My grandmother claims it helps her knee pain. The raw ingredient of feni comes from cashew plantations– a dominant feature of the landscape. Given my Konkani roots, and that I was a wildlife biologist in training, I became interested in understanding how cashew plantations can serve as wildlife habitat. For my study, I chose the Tillari bioregion nestled deep in the Western Ghats of Maharashtra, where cashew is an important cash crop and feni, an intoxicant for locals.

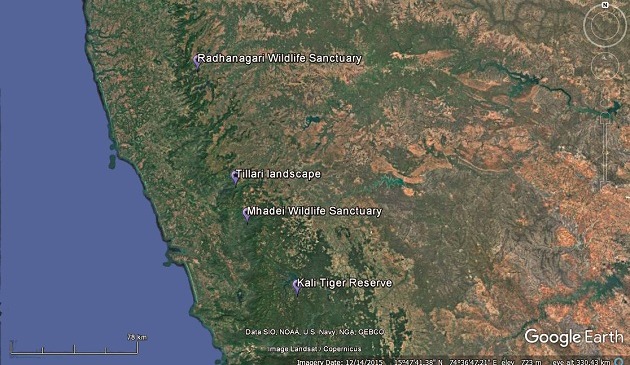

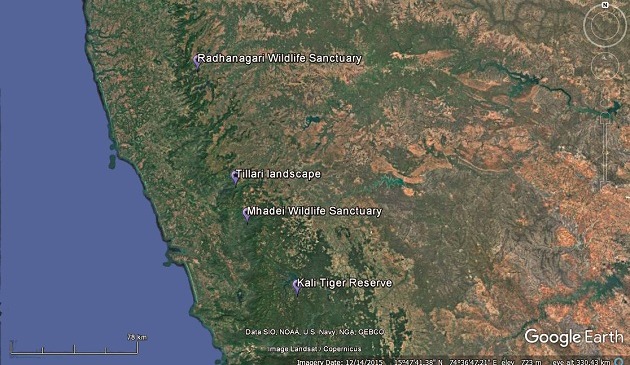

Tillari is situated in Maharashtra’s Sindhudurg and Kolhapur districts and forms part of the corridor between the state’s Radhanagari Wildlife Sanctuary, Karnataka’s Kali Tiger Reserve and the Mhadei Wildlife Sanctuary in Goa.

The bamboo-rich forests that fringe the cashew plantations are home to tigers, leopards, dholes, gaur, sambar, chevrotains, muntjacs, wild pigs, civets, mongooses, Indian crested porcupines, black-naped hare, small-clawed otters, pangolins and even Asian elephants! For my Masters dissertation, I studied how mammalian habitat-use changed across different land use types. In a densely-populated country like India, wild animals have no choice but to use human-modified spaces, which are embedded among native habitats. But what makes such spaces conducive to mammal movement or use? While scientists have studied how wild species use forest-plantation landscapes, such as coffee, tea, rubber, and oil palm, knowledge about cashew is still limited. India is the world’s third-largest exporter of cashew. Not intensively managed, the plantations are left relatively undisturbed, except during the fruiting season in summer. Konkan has a diversity of land use types. Forests are classified into either Reserved Forests (RF), which are government controlled; or under private or community ownership called malki jungle with the former being better protected. Malki jungle areas are largely secondary forests, that have suffered repeated felling cycles for extraction of wood or for swidden agriculture (now considerably reduced). Cashew forms a livelihood source for many families and is grown on private monoculture plantations, though they are rarely fenced. Smaller patches are planted with areca nut, coconut, banana and sometimes with rice or millet. In recent years, rubber plantations (for which I failed to get camera-trapping permission) have become the vogue.

Camera-trapping in the Countryside

I used camera-traps in a systematic grid design to understand habitat-use by terrestrial mammals in both forests and cashew plantations. The three months spent in the field were nothing short of a disciplined military routine. Early each morning, my field assistant Narayan kaka and I would set off to check camera-traps located far apart for photographs of different species and individuals. We would retrieve 12 camera-traps and place them in an equal number of new locations for the next 24 hours. Starting out from my field base in Hewale village, we covered Medhe, Mulas, Palye, Sonaval, Ghotgewadi and Konal. This involved walking through hills and mountains to examine trails and riverbeds to choose the best locations to place camera-traps. Like detectives at work, we would scan potential sites for scats, pellets, scrape marks and sometimes argue about the positioning of the cameras. Narayan kaka was an expert on animal poop; he could usually determine not just the species from the poop, but even how recent it was based on consistency and odour. Soon I learned kaka’s sniffing skills and the walking helped me hone my own senses better. Slowly I came to realise how attuned my ears could be to sounds and how oriented my feet to directions… provided I concentrated my focus on the silence of the jungle.

Porcupines made a regular appearance on camera traps installed by the author, who encountered their signs frequently during her field work. Photo Courtesy: Anushka Rege

On early morning walks, the calls of Racket-tailed Drongos and the whistle of the Malabar Whistling Thrushes would be supplemented by the urgent calls of Malabar Barbets, with calmer ones from Coppersmith Barbets more prevalent in the afternoons. In open spaces near fallow rice fields, we often saw black-naped hare. One night, we chanced upon a porcupine and a brown palm civet calmly crossing our path. I never could capture a brown palm civet on my camera-traps, possibly on account of their largely arboreal habits. On the Tillari river bank, we often came across spraint, both fresh and old, although we never attempted to capture the otters on our camera-traps.

The camera traps gifted the author several mongoose images near cashew plantations and human settlements. This one, of a grey mongoose, was kaka’s favourite. He nominated it as the ‘poster perfect shot’. Photo Courtesy: Anushka Rege

Locals testified that gaur were common, but until the last three days of field work I saw none. The last sighting was memorable. A gigantic lone bull stood in our way for a good five minutes before reluctantly allowing us passage. But perhaps our most unforgettable sighting was one of a pair of adult dholes that had just killed a sambar doe in a river. Peering from behind some bushes, we watched seven pups join the two adults as the pack fed for over 30 minutes.

The winds of seasonal change were palpable. The mild winter months went by in a flash, and soon it was the onset of summer. Though we sometimes cursed the humid weather, we also enjoyed watching yellow leaves fall onto the forest floor, with red leaves of the kusum tree Schleichera oleosa bursting forth from the branches. Shades of greens turned to yellow, red, and then bright green again. The melodies of songbirds accompanied us on forest trails, when we often stopped to gorge on kokam (Garcinia) fruits, kairi (raw mangoes) and karvanda (Carissa carandas).

Conversations with Kaka

The sagely and mystic Narayan kaka is a touch over 50-years-old. An experienced forest walker, he also learned fast how to operate cameras and to use the GPS. He loved setting up camera-traps and there was never a dull moment with him, even when the weather was rough and the climbs arduous. When we stopped to rest, we would eat some bhakri (a local bread) that his wife would lovingly prepare for us. Sitting by the riverside, he would tell me fanciful folktales of the scheming wives of a man who lived atop the cliffs and of tigers that leaped to their doom off the same cliffs. The thread of cashew feni was woven in our discussions ever so subtly. Every time we passed through cashew plantations in the summer, we would see piles of ripe fruits, soon to be sold for producing feni. When we spotted rotten red fruits in the piles of yellow, Narayan kaka would mutter under his breath about how the prized fruit had been wasted. Walking through the flowering bamboo forests was a delight, but we had our share of troubles too. Two of our cameras were stolen, possibly by hunters in the region who feared being identified. When trails disappeared, we would crawl through dense vegetation over steep hills and valleys. Our camera-traps sometimes revealed no images at all, but we kept our spirits up in each other’s company… to the accompaniment of unending folk tales.

Narayan Desai (kaka), the author’s field assistant, took an immediate liking to the setting up of camera traps and the rigours of field work. Photo: Anushka Rege.

Back at the field base in Hewale around noon each day, we would head straight to the desk to view the previous day’s photos. Other field researchers or even locals, if they were around, would gather keenly around my laptop as image after image flashed past.

Our first photograph of the study was a small Indian civet in a cashew plantation. Soon, photos of porcupine, Indian grey mongoose, sambar, gaur, wild pig, and black-naped hare began rolling in. Rarely, a shy chevrotain, common palm civet or Indian muntjac would appear in our photos. Leopards too… one just a few hundred metres from our field base. We even got a melanistic leopard (black panther) in a cashew plantation and our field office was filled with gleeful squeals!

The first camera-trap image of a leopard in a cashew plantation obtained by the author. Locals often see leopards around their farms, and consider them to be sacred animals. Photo Courtesy: Anushka Rege

The People of the Plantations

Without the support of locals, my project wouldn’t have succeeded.Setting up camera-traps on community and private lands was a large part of my fieldwork. Initially, they thought I was there to displace them, nab hunters and report them to the Forest Department. It took us a full month to convince them of my bonafides, after which I received heart-warming support and hospitality.

The locals have a long tradition of hunting. Although the aspiring conservationist in me wanted to ask them to stop, I thought better of it. Miles from basic amenities, wild meat constitutes a no-cost source of protein and wild animals often raid their crops or kill their livestock. In such circumstances, ‘coexistence’ is a thin line, and walking it is easier said than done.

One hot afternoon, Narayan kaka turned to me and said, “Please let your juniors know about this place and me, I will work like this again happily, I like this work. People kill a wild animal, they eat it once and save a days’ worth of money, but if they preserve it, then many tourists and researchers will visit and we shall earn more. If more people come, it will mean more employment for the village folk.” His words were music to my ears! If more villagers felt this way, we might be onto something. But optimism often fades in my profession, particularly when stories of wildlife killings kept coming our way. When the animals killed included my study species, it was difficult to remain unemotional. But we engaged with grit and determination and continued explaining how living wild animals would be better not only for the forest upon which they were dependent, but also for many of them because a biodiverse forest could bring visitors and revenue.

Our camera-traps captured nine mammalian species in cashew plantations, proving without doubt that these areas could offer wild species such as sambar, wild pig, and porcupine some refuge. But statistical quantification of habitat use by other species remained elusive. I concluded that sambar and porcupine tended to use both forest and cashew, whereas wild pig preferred areas closer to human habitation. Locals informed us that all three species debark cashew trees and consume the fruit.

A cashew plantation against a backdrop of wild bamboo. Photo Courtesy: Akshata Karnik

Tillari Forever

Tillari faces two major issues – land use conversion and hunting. Cashew and rubber have eaten away at forested areas in the past decade. Lands under private ownership have been burned and used to grow crops, while trees have been felled for timber. In days of yore, when swidden agriculture was practiced, biodiverse forest lands would be left alone to recover and could therefore support wild creatures. But with the advent of cash crops, the biodiversity value of such lands plummeted. Cashew plantations are used by some terrestrial mammals since they are unfenced. Not so the rubber plantations that are all-too-often solar-fenced. Hopefully studies will help us understand how such plantations can be better managed to enable biodiversity to survive.

Rubber plantations have replaced entire facades of mountains, transforming previously lush forests into monoculture nightmares. Courtesy: Google Earth

Tillari forms part of an important inter-state forest corridor between Maharashtra, Karnataka and Goa. Photo Courtesy: Akshata Karnik

Hunting is, of course, a huge problem and persists to date. Educating locals and offering them livelihoods that are predicated on biodiversity regeneration could help lower hunting levels. Sustainable nature tourism with local communities as the primary beneficiaries would undoubtedly reduce people’s dependence on wild meat and reduce human-animal conflict.

The wildlife corridor we would like to see protected has value beyond mere passage for species. This is also part of the Tillari water basin upon which downstream farms and plantations are totally dependent. A huge section of people, from the hill villages of Hewale, all the way down to the coastal towns and villages of Goa, depend on this water.

This, if nothing else, should be reason enough for us to win support for the protection of the living forests of Tillari.