Doting Dads And Marauding Males

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 38

No. 11,

November 2018

By Seshadri K.S.

That cold September night in 2011, we had driven all day to reach a point where an old rickety wooden bridge lay across the headwaters of the Manimuthar river. The rains from the southwest monsoon had nearly ceased. I got off the field vehicle and walked into the Ochlandra bamboo clump along the river bank. The trail was narrow and a slip posed the risk of serious injury. Moreover, elephants used the trail frequently and the chances of running into them were high. In the darkness, I was attracted to a feeble call from a bamboo clump. Shining the light in that direction, I found a small frog perched on a bamboo stalk and calling. I gestured to my colleagues Dr. Ganesh T. and Prashanth M. B. to take a look. All of a sudden, the frog stopped calling and began to squeeze into a narrow cavity on the bamboo stalk. I quickly recorded it, only to realise later that this was the first time such behaviour was being witnessed or filmed. This incident triggered several thoughts in our minds. Why should a frog struggle to get into the bamboo? Did it spot a predator and seek shelter inside?

Photo: Dr. Seshadri K.S.

In the Jungle, Deep and Dark

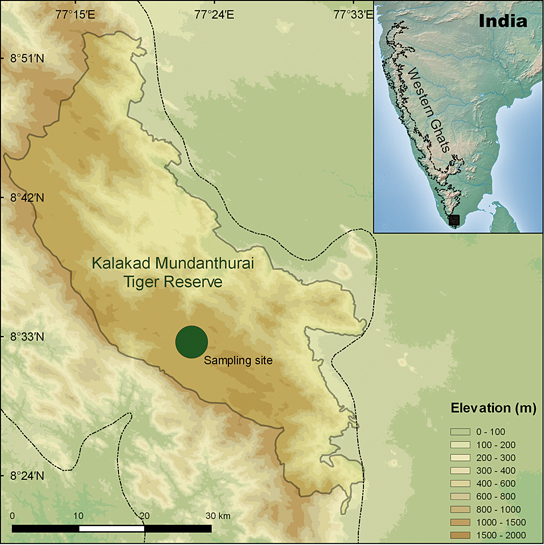

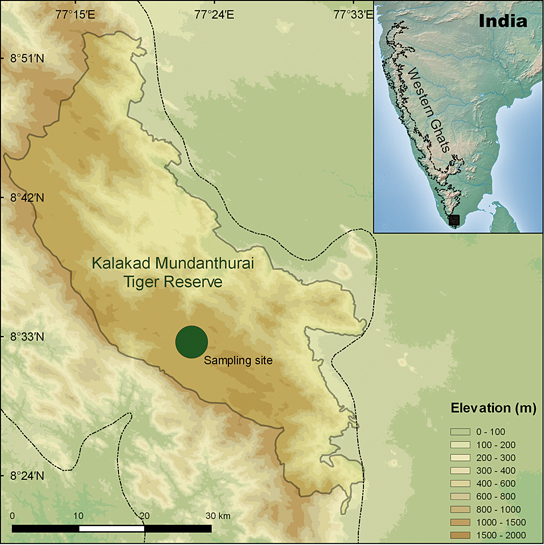

Over the next seven years, my urge to find answers took me to the remote forests of the Kalakad-Mundanthurai Tiger Reserve (KMTR) in Tamil Nadu. The lush forests of KMTR are resplendent with life, ranging from orchids such as Eria pauciflora and the uncommon Kalakad gliding frog Rhacophorus calcadensis in the canopy to the diminutive plant paradise, Balanophora and the tiny Beddomes night frog Nyctibatrachus beddomii on the ground. The landscape is serene with large tracts of undisturbed forests fragmented by tea plantations. Large mammals such as elephants, sambar, tigers, leopards and, wild dogs continue to be seen through this landscape, including in the tea plantations. The region receives nearly 3,000 mm. of rainfall in two distinct phases, the southwest and northeast monsoons. At night, the forest comes alive with a myriad life forms including creatures such as the flying squirrel, Malabar spiny dormouse, brown palm civet, leopard cat, small-clawed otter, Brown Fish Owl and the Oriental Scops Owl. On a lucky night, all might be encountered, including the 25-odd species of frogs known from the region!

A Quest for the Elusive

The frog in question is Raorchestes chalazodes, commonly known as the white-spotted bush frog. It is a small, arboreal amphibian measuring up to 26 mm. belonging to the tree frog family Rhacophoridae. The Western Ghats is home to over 50 species of frogs belonging to the genus Raorchestes. The white-spotted bush frog was lost to science for over a century as no reliable sightings were reported since its description way back in 1874. It was subsequently ‘re-discovered in 2011 from a remote corner of KMTR. This green coloured frog has a bright yellow (adorable) star-burst pattern in the eye. Virtually nothing was known about it when I first set my eyes on it; with new species of frogs being described every year, it was hardly a surprise.

The next morning, I returned to the bamboo clump and carefully split the stalk to find the frog sitting inside the hollow with a cluster of white-coloured eggs. This was a surprise. In school, we are all taught that frogs lay eggs, from which hatch tadpoles, which then transform into frogs as we know them. But there was something else going on here - there were eggs, but no water! After taking pictures, I carefully joined the stalk with some tape and left to read more about this interesting find.

Photo: Dr. Seshadri K.S.

Stumbling Blocks and Stepping Stones

I had stumbled upon behaviour known as direct development - where frogs have evolved a strategy to reduce their dependence on water by laying eggs that hatch into tiny froglets in terrestrial habitats, away from water. Frogs evolved from fish-like animals nearly 360 million years ago and it would be impossible to cut off the connection with water. Therefore, frogs lay eggs where humidity is high with enough moisture for the eggs to develop. I went back to the bamboo patch over consecutive monsoons to find many more such cavities on bamboo stalks and frogs with eggs. Each time, it was the male frog. In most species, female frogs do not call and because the frogs were calling from both inside and outside of the stalks, clearly they were all males. The frogs were entering the stalks of a reed bamboo called Ochlandra travancorica, found only in the Western Ghats. About 2.6 cm. in length and 1.5 cm. in width, the frogs occupied bamboo that was roughly 2.8 cm. in diameter, a tight squeeze! All these observations gave rise to another question - why was it the male that we inevitably found with the eggs?

A few years later, I pulled out my field note book and began discussing these observations with my PhD advisor, Dr. David Bickford, at the National University of Singapore. I came to realise that just like we humans take care of our children, many animals care for their young ones and thereby enhance their chances of survival. The frogs were exhibiting parental care behaviour. Infact, their reproductive behaviours are diverse and researchers have classified them into ‘reproductive modes depending upon where the eggs are laid (in water, or on leaves), what kind of eggs (direct vs. non-direct developing) and whether or not parental care was involved. Comparing my notes with published behaviours - we realised that we had discovered something new. Individuals of R. chalazodes lay eggs that hatch into froglets inside hollow bamboo internodes, devoid of any water… and males appear to care for the eggs. Similar behaviour was reported in a charismatic frog of the Western Ghats with a star-burst pattern in the eye, aptly named Raorchestes ochlandrae after the Ochlandra setigera bamboo stalks, from within which the frog was found. We, therefore, reported it as a new behaviour for all the frogs known so far.

Photo: Dr. Seshadri K.S.

Evolutionary Significance of Parental Care

Parental care behaviour is costly as the caring individual is often unable to go in search of food and must spend additional energy defending off-spring. Why then do male frogs sit with the eggs? Such behaviour must have evolved for a reason and by definition parental care should enhance offspring survival. I found males inside the bamboo reeds but observing them without cutting open the bamboo was a challenge. A bit of searching in a hardware store resulted in a solution - pipe inspection cameras or endoscopes where a small camera is attached to a wire and a display screen. Every night, my colleagues and I would carefully inspect hollow bamboo cavities to see what was going on inside and document the behaviour of the male, making nearly 1,200 observations in the process. We measured aspects such as number of eggs, activity of the male frog and behaviour.

Science can sometimes seem callous, but it is most certainly not. What we discover at the cost of a handful of specimens, often quite literally helps us to save thousands of members of our study-species. We noticed, for instance that male frogs (often next to or on eggs) would sometimes attack the endoscope, calling aggressively. To understand why, I carefully nudged the males out to see what happens. I did this while retaining the male in another bamboo stalk as a ‘control. Soon, the eggs without any care started to die. We observed ants eating eggs and some infected by fungus. On one night I saw a frog in the manipulated stalk from which I had removed an amphibian. When I nudged the male out, I discovered four eggs missing. It took me little time to understand what had taken place. The missing eggs were in the stomach of the intruder male as evidenced by its distended abdomen! As it turned out, parental care by males is also key to protecting eggs from cannibalistic males of the same species.

This was a new discovery among frogs in India.

Studying frogs in their natural habitat turned out to be both incredibly challenging and rewarding. Although my research was back-breaking, I was richly rewarded with unique insights. Why do frogs cannibalise eggs? Perhaps because frogs eggs are a good source of nutrition. Or because males that ate others eggs were starving males guarding their own eggs. Or perhaps they were just looking for bamboo stalks to call home and so woo a female. But can frogs recognise their own eggs? Again, I was left with more questions than answers. Over the years, more parental care behaviours have been observed among frogs in India. For example, the male frogs of Nyctibatrachus kumbara stand on two legs and cover the eggs with mud. This is probably to protect them from predation. Its all conjecture. We just do not know yet.

Photo: Dr. Seshadri K.S.

A Unique System in Threat

All the while, there was another, larger, question rattling around in my mind. Who was responsible for the holes on the bamboo which the frogs used to enter? Dr. Ganesh had suggested a likely suspect based on the bite marks on the bamboo - the dusky-striped squirrel Funambulus sublineatus. On many mornings, we saw them nibbling on the bamboo stalks, eventually making a hole. The frogs were somehow keeping track of these holes and using them to breed. The squirrel, the frog and the bamboo are only found in the Western Ghats. All three face extinction and are listed as threatened in the IUCN Red List. The bamboo is cut for paper and pulp industries and for local consumption. If the bamboo is extracted during the breeding season of the frogs, their population will be drastically impacted. If for some reason, the squirrel populations decline, the cavities will no longer exist and neither would the frogs, which exclusively breed in bamboo. In fact, a few years ago, researchers even discovered a new species of frog, Raorchestes manohari inside bamboo that was being transported on a truck to a paper factory! There is clearly an urgent need to understand to what extent bamboo is threatened from harvesting, especially because ‘bamboo products are being promoted as eco-friendly as it grows profusely.

In November 2017, bamboo was removed from protection under the Indian Forest Act (1927) on the ground that, technically, it is a grass. This opens up the possibility of unregulated bamboo harvesting. This could be disastrous for these frogs whose entire existence depends on the bamboo. We must understand the dynamics of this unique interaction to ensure that the bamboo habitats, squirrels and frogs survive. The future of all three species is inter-twined and protecting wild bamboo is the very least we can do for the doting dads sitting on vigils inside the bamboo, guarding their eggs night after night!

Photo: Dr. Seshadri K.S.