Forest Fires, Elephants and People

First published on

April 30, 2021

The fate of forest conservation in Wayanad, Kerala

by Anoop N.R. and T. Ganesh

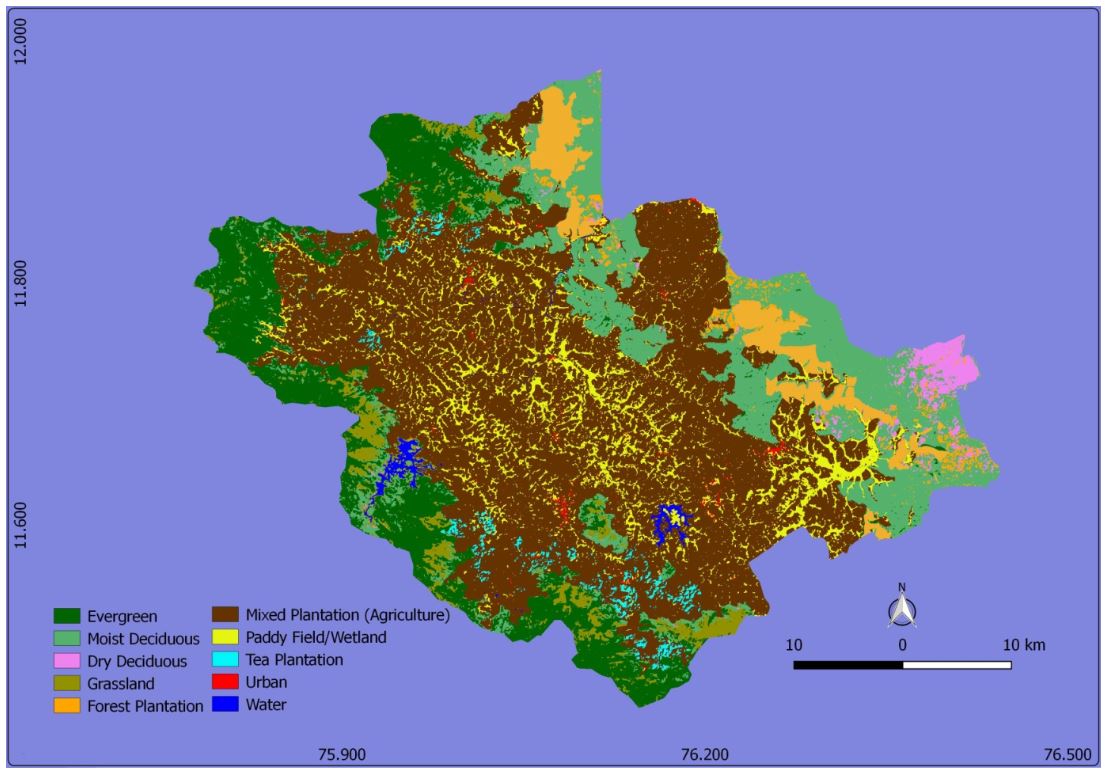

Wayanad is a gentle, east-sloping plateau that merges with the drier Mysore plateau in the east. Peppered with rich low-lying swamps and meandering streams, the north Kerala district remains a heavily forested district despite experiencing large-scale land-cover change during colonial rule. The migration of people from Travancore in southern Kerala after World War II inevitably led to forests and wetlands being wiped out to address the food crisis. As a result, Wayanad forests were fragmented into two narrow tracts along their western and eastern borders (see map below). The western forest belt is mostly evergreen and highly fragmented, while the eastern forest belt is deciduous and connected to the Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve (NBR), a globally important conservation area.

Wayanad plateau offers a unique geography of small, emergent hills interspersed with slushy swamps.

During summers, when the carrying capacity of adjoining dry forests in Karnataka and Tamil Nadu reduces, Wayanad with its vayals (swamps) and perennial water sources becomes the key mico-habitat for elephants and other large herbivores. However, these forests are highly vulnerable to rampant human-caused fires that wreak havoc across the habitat and intensify human-wildlife conflict in the region. Despite the adverse consequences for both wildlife and people, few studies have delved into the impact of fires on the NBR ecosystem.

In February 2019, my field assistant Chandran and I were in the Wayanad Wildlife Sanctuary, sampling elephant dung as part of my Ph.D. work on the ecology of Asian elephants. In the afternoon, we received a message from a friend, warning us to refrain from sampling in Vadakkanad village, where people had allegedly started a fire in the forest. In the following two days, fires were started in six different sites near the village, destroying about 60 hectares of forest.

We approached a forest department official (who wishes to remain anonymous) to understand why this was happening. He told us, “The fire was intentionally started because of the animosity of villagers towards the forest department, which was unable to capture a bull elephant locally known as the Vadakkanad Komban and had been noted to persistently raid crops in the area. Burning the forest was a form of protest against the Forest Department and the elephant."

Forests and Fires: the Aftermath

Tree cover, abundant leaf litter and humus in the soil work together to allow the percolation of water during rainfall and moist weather. This is vital to sustain streams and vayals during the summers. Fires can adversely affect percolation, trigger soil erosion and dry up water bodies. The unavailability of water can severely affect forest dynamics, leading larger numbers of animals to encounter one another at scattered water resources.

At the height of dry season, this large bull spend hours in the swamps due to the availability of shade, water, slush, forage and unique micro-climate.

A herd of elephants forage in the high altitude grasslands of Brahmagiris.

Invasive species like Lantana camara and Senna spectabilis tend to spread widely across fire-ravaged and degraded areas, hindering the growth of native vegetation and accumulating biomass that can further fuel future fires, creating a positive feedback loop. Such species are non-palatable for herbivores and can have serious implications on the ‘fitness’ of megaherbivores like elephants, which consume vegetation in huge quantities. In the absence of their natural diet, elephants may leave the forests in search of food, leading to conflict situations with people. There is growing evidence in Wayanad that Lantana camara can be wiped out from the forests, if fires are prevented from sweeping across the landscape frequently, allowing regeneration of native vegetation. This has been observed in the Pazhupathur section of Wayanad Wildlife Sanctuary, Chethalayam Range and Ondayanagadi Reserve Forests in the North Wayanad Forest Division, where consistent monitoring of fires has done wonders for the health of the forest.

The vegetation of any healthy forest emerges in several layers, with different plants growing to varying heights and sizes. But if you walk through the deciduous forests of NBR, you are likely to find only tall trees, on account of the high mortality of seedlings and saplings after fires. The undergrowth in these forests are mainly dominated by Lantana camara. Uncontrolled fires can cause the total devastation of some species due to their ecological and evolutionary peculiarities. The fire also kills trees that are weak or not well-adapted to fire. Bamboo is common in the Wayanad forests and is important for maintaining the microclimate and providing food for elephants. Gregarious flowering of bamboo Bamboosa sp. occurs every 40-50 years and the plant dies after producing seeds. Fires during the flowering and fruiting season can destroy the seed bank, devastating the entire population of the plant. This was observed during the mass flowering of bamboo in Begur forest range from 2008 to 2010, leading to poor regeneration of bamboo, among other species.

Fires and Conflict: the Link

Human-elephant conflict (HEC) majorly affects local support for biodiversity conservation. Our study on HEC in Wayanad revealed that conflict has escalated over time, and tolerance of people has reduced.

Many of Wayanad's wetlands are increasingly being wiped out for growing paddy in the last century.

Frequent fires and widespread urbanisation have left a scarcity of food in forests, leading elephants to venture out onto paddy fields.

A farmer from Vadakkanad said: “There was no ‘elephant problem’ when I bought this land in the late 1960s. It was very fertile, allowing us to cultivate varied cash and food crops. During this time, elephants were afraid of us -- they would run away when they saw us. Guns were common and there was no restriction on using them to hunt wildlife or drive elephants away. Now, elephants and other wildlife frequently enter our lands, and we don’t know what to do. I think this is happening because of rising wildlife populations, loss of fear of people, unavailability of food and water inside the forest owing to expanding teak plantations and invasive species. Corruption and apathy too impact conflict resolution. The Forest Department rushes to the scene when a tiger or elephant has died or if there is a fire but does not come to our rescue."

These forests are already heavily fragmented and degraded due to various anthropogenic pressures, and unmonitored fires can only further deteriorate their condition. Conflict in the region can be expected to escalate further, if forage becomes increasingly unavailable to wildlife, a situation only worsened by the spread of invasive species and water shortages.

An Urgent Eco-restoration Plan

Wayanad’s rich, biodiverse forests are important for the survival of not only its wildlife, but also its people. We must come up with efficient strategies to manage the remaining vegetation and restore degraded parts of the forest, and rewild monoculture plantations. An urgent eco-restoration programme needs to be devised for the landscape, involving local communities, who must be made aware of the issues. It is obvious that urgent solutions that focus on wildlife conservation awareness among locals as well as sustainable successful solutions that protect crops and livestock from wild animals is key to ensuring that locals are not antagonistic to wildlife conservation.

Currently pursuing his Ph.D. on the ecology of Asian elephants at Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and the Environment (ATREE), Anoop N.R. is actively involved in biodiversity conservation in the Wayanad plateau in Kerala and hopes his doctoral research will contribute to the protection of elephants and the well-being of rural communities.

A senior fellow at ATREE, T. Ganesh works to understand how wild species and their ecosystems adapt to natural and anthropogenic changes over time.