Indian Ornithology: A 40-Year Legacy

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 41

No. 10,

October 2021

By Asad Rahmani

The first scientific book on Indian birds was written by T.C. Jerdon, a British botanist, zoologist and physician, in 1862-64 in two volumes, covering over 1,000 species. This pioneer naturalist was also instrumental in the birth of The Fauna of British India, including Ceylon and Burma series. For the next 100 years, many books and research papers were written, mainly describing new species and their distribution, culminating in Ali and Ripley’s 10-volume Handbook of the Birds of India and Pakistan, the first volume appearing in 1968 and the last in 1974. In this article, I am not going to describe the history of ornithology in India – for that I suggest Sanctuary subscribers turn to the excellent writings by Bikram Grewal. Bikram’s talk on this subject is as riveting as his articles. I will deal only with the recent four decades, to commemorate the ‘birth’ of Sanctuary Asia magazine in 1981, edited by my friend, Bittu Sahgal.

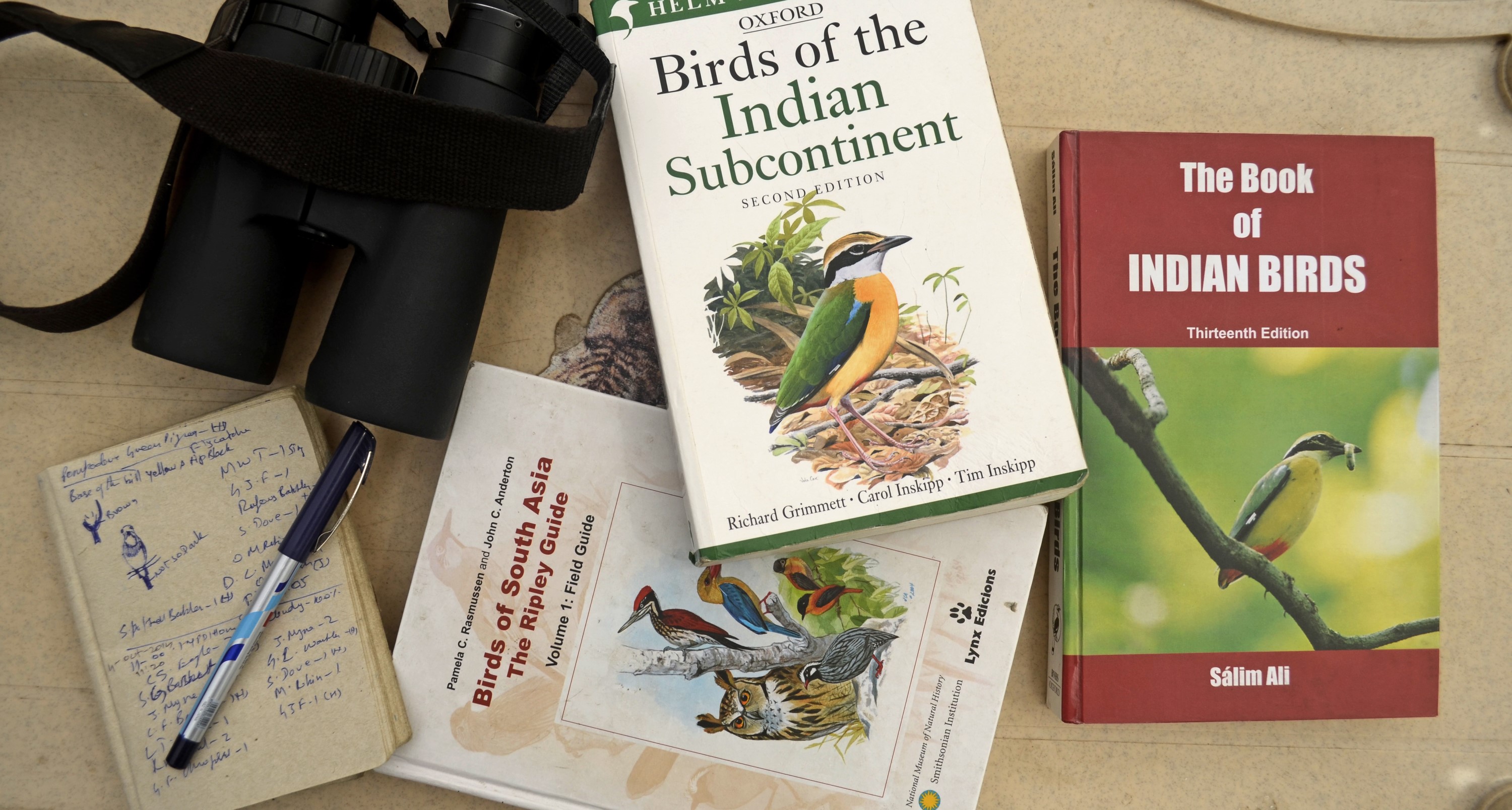

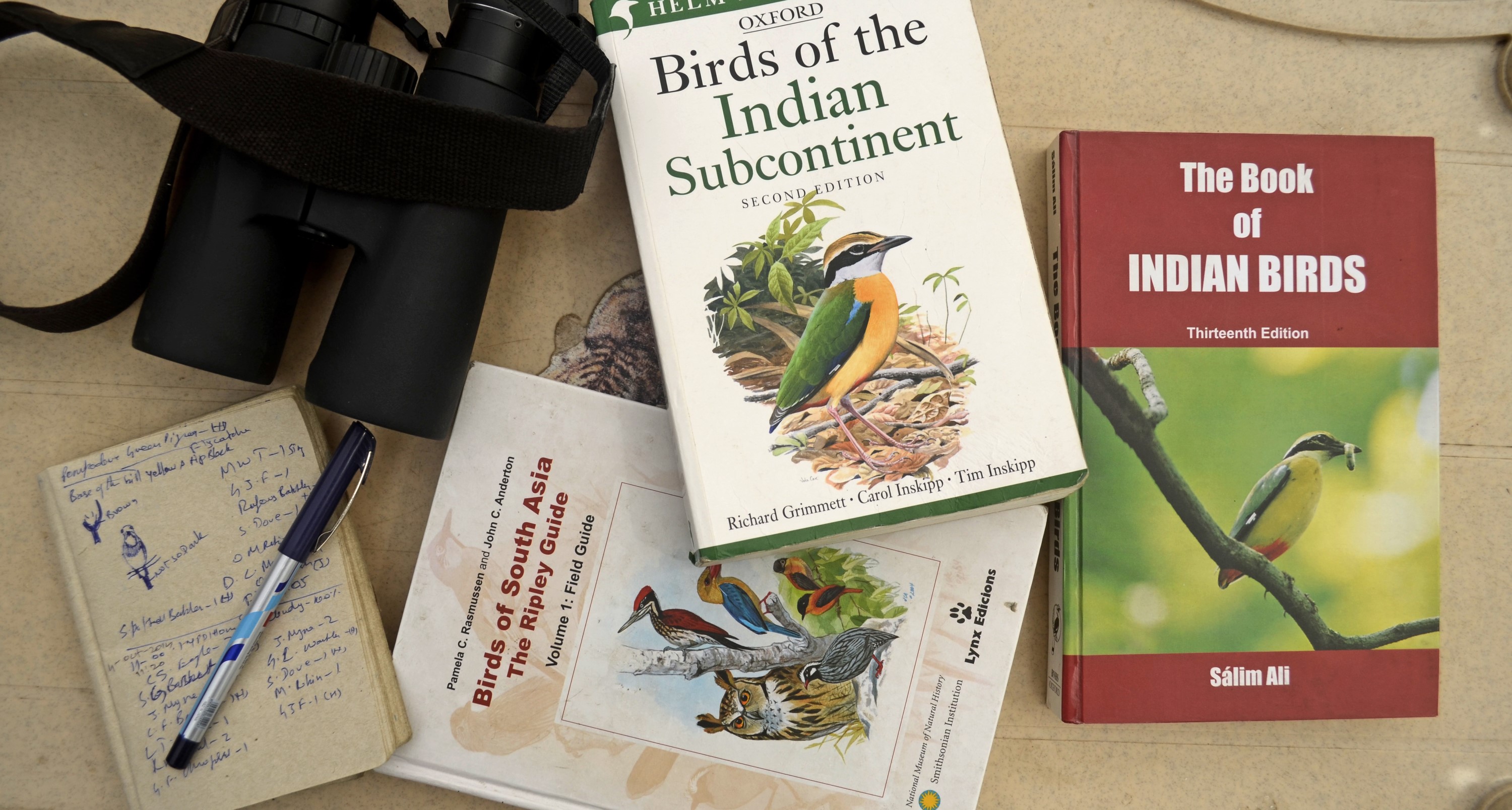

Birdwatchers’ Bibles

The year 1983 marks a crucial time for the Indian conservation movement. It was the year the Bombay Natural History Society (BNHS) celebrated its 100th birthday. Along with other centenary-celebration events, Indira Gandhi released BNHS’ A Pictorial Guide to the Birds of the Indian Subcontinent – written by two doyens, Dr. Sálim Ali and Dr. S. Dillon Ripley – at a glittering ceremony in Mumbai’s famous National Centre for Performing Arts (NCPA). This was the first Indian bird book that had illustrations, by John Henry Dick, of all the known species of the Indian subcontinent. Despite its few weaknesses, the book was a sell-out and became a standard companion of birdwatchers. Over 16,000 copies have been sold. I am a proud owner of a signed copy by both the authors.

Another book that helped birdwatchers in the 1980s and 1990s was Collins’ Field Guide to the Birds of South-East Asia, which included many species common to India. The real change and challenge came in 1998 when Richard Grimmett, Carol Inskipp and Tim Inskipp brought out their Pocket Guide to the Birds of the Indian Subcontinent, published by Christopher Helm Ltd., U.K. Its popularity in India was instant and resulted in its re-publication by the Oxford University Press in 1999.

Birdwatchers and ornithologists long-used to James Lee Peter’s classification (used with some modification by Ali and Ripley in the Handbook) suddenly found an entirely new bird species sequence largely based on Distribution and Taxonomy of Birds of the World by C.G. Sibley and B.L. Monroe Jr., published in 1990. The taxonomic sequence was based on genetics and other objective methods of assessment. Several English bird names were also changed. For example, some woodpeckers became flamebacks, the White Ibis became the Black-headed Ibis and so on. Indian ornithologists who grew up using the Handbook and Pictorial Guide could not understand (or digest!) why Grimmskipps’ (the popular combined name) book started with quails, pheasants and then ducks, and after that woodpeckers, barbets, hornbills, and bee-eaters. But the plates were excellent, a combined effort of 12 illustrators, including our own Carl D’Silva. But the taxonomic sequence was ‘wrong’ according to many old-timers like me and we struggled in the field to find and match names with illustrations. The real ignominy would be when a veteran would tell a young ornithologist that he or she had not seen a Striated Grassbird, not realising that it was in fact the Striated Marsh Warbler with a new moniker.

A staunch wildlife conservation supporter, Indira Gandhi launched the Bombay Natural History Society’s A Pictorial Guide to the Birds of the Indian Subcontinent in 1983, in honour of the institution’s 100th birthday. Photo Courtesy: Jairam Ramesh

A New Millennium

In 2000, a little-known Krys Kazmierczak brought out Birds of India, Sri Lanka, Pakistan, Nepal, Bhutan, Bangladesh and the Maldives, with illustrations by Ber van Perlo. It was first published by Christopher Helm, and later by Om Books International, New Delhi, in 2009. It followed the Handbook classification and, for a while, became very popular. Some people preferred its bird illustrations over those of previously published books, others found the plates cluttered. But the maps were undoubtedly good.

For another six years, we all struggled with Grimmskipps’ book and we were relieved when Pamela Rasmussen and John C. Anderton brought out their two-volume Birds of South Asia: The Ripley Guide. They followed the Handbook bird sequence (first listed by Dillon Ripley in 1961 in the form of A Synopsis of the Birds of Indian and Pakistan), but split many species and upgraded some subspecies to species. For example, the Slender-billed Vulture, long considered as a subspecies of the Long-billed Vulture was upgraded to a species level, based on almost 80 morphological and behavioural characteristic differences between the two species. Similar was the case of the Indian Spotted Eagle, once a subspecies or a race of the Lesser Spotted Eagle. Dr. Rasmussen also hyphenated the compound words, which was not the case with the Handbook. Thus, the Redwattled Lapwing became the Red-wattled Lapwing and the Longtailed Broadbill became the Long-tailed Broadbill.

In the early 2000s, there was steady evolution in the then-nascent science of ornithology as newer publications highlighted clear differentiations between avian subspecies and species. For instance, the Indian Spotted Eagle, earlier considered a subspecies of the Lesser Spotted Eagle, was now classified as a separate species. Photo: Public Domain/Chinmay Isk.

Post the 1990s, global travel become more frequent, and it was felt that birders needed greater standardisation of common names. Many birds were, after all, found in multiple countries, but were known by different English names. Understandably, this created confusion with itinerant, amateur birdwatchers. Openbill Storks, for instance, are found in Asia and Africa but are entirely different species, yet in both continents, they were known as Openbills. It eventually became a necessity to refer to them based on their distribution, as Asian Openbill Anastomus oscitans and African Openbill Anastomus lamelligerus. Similarly, numerous changes took place with the common names of birds.

India’s liberalisation policy of the 1990s and the beginning of a new millennium saw a boom in wealth, particularly within the IT sector, and access to photography equipment grew rapidly. Overnight bird photographers sprang up. One who could not even identify common birds could produce stunning images. This resulted in a glut of image-heavy bird books, of which the most remarkable was A Pictorial Field Guide to Birds of India by Bikram Grewal, Sumit Sen, Sarwandeep Singh, Nikhil Devasar and Garima Bhatia in 2016. It included as many as 1,300 species, all depicted by outstanding photographs.

Several notable books in ornithology have contributed to the rising interest in birdwatching across the world. Photo: P. Jeganathan/Public domain.

Other Notable Contributions

It would be difficult to mention all the bird books and thousands of research papers and articles on birds published during the last four decades, but some books stand out. My personal favourite is Dr. Satish Pande’s seminal Latin Names of Indian Birds Explained, published jointly by the BNHS and OUP in 2009. A scholarly work by a medical doctor, this book underscored the immense contribution of amateur birdwatchers to Indian ornithology.

Aasheesh Pittie, a BNHS life member and an amateur ornithologist, developed a bibliography of Asian ornithology that totals an impressive 34,700 references. As a young man in the early 1980s, he started filing a rudimentary index of articles on foolscap papers, under keywords based on bird and place names. The idea was to quickly locate any published material using keywords, to access information beyond what the extant books contained. Within a decade, he computerised his data and his bibliography is now the most comprehensive database on Asian birds.

As global travel opened up post the 90s, birds such as the Openbill Stork, which are found in both Asia and Africa, had to be renamed with appropriate prefixes – Asian Openbill (above) and African Openbill – to avoid confusion among amateur birdwatchers. Photo: Atul Dhamankar.

A search of this bibliography reveals that from 1981 onwards, a total of 22,965 references were added, including 18,643 journal articles, 1,268 books, 219 edited books, 1,771 book sections, 152 thesis, 562 unpublished works, 81 webpages, and 269 miscellaneous. This clearly demonstrates the growth of Indian ornithology during the last four decades.

For quite a while, the Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society, or JBNHS, and the Newsletter for Birdwatchers (started in 1959) were the journals of choice for those wishing to publish their bird observations. In the mid-2000s, Aasheesh Pittie and his team started Indian Birds, a journal that has now become a favourite for birdwatchers. The Journal of Threatened Taxa (JoTT) also publishes many papers on birds, but Indian Birds is exclusive to Asian birds. Sanctuary Asia too played a key role in encouraging youth to observe, study and photograph birds.

The Striated Grassbird, so named for the prominent black streaks on its back, is an ‘Old World warbler’ with an extremely wide distribution across Southeast Asia. It prefers the edges of fields, dense thickets and scrubland habitat. Photo: Public Domain/J.M. Garg.

As ornithology slowly, surely spreads its wings across India over the years, it was also felt that the data collected by amateurs needed to be collated and made available on an easily accessible platform. That gave rise to eBird, which listed the status of India’s birds primarily using data uploaded by thousands of birdwatchers. eBird-India is an ongoing programme, linked to a searchable global database that collates data on birds to understand their distribution, changing status and conservation requirements. Of the 1,320 odd species reported from India, 867 were assessed and an excellent report was released in February 2020 at Gandhinagar, Gujarat during the Thirteenth Meeting of the Conference of the Parties to the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS COP13).

Clearly, we have come a long way from the time when a lonely T.C. Jerdon published his first book on Indian birds in 1862. Today, India has hundreds of thousands of birdwatchers, in addition to thousands of conservationists and NGOs, all working to make our country a better, safer place for our feathered denizens.

Asad Rahmani was the Director of BNHS (1997-2015), he has authored several books, scientific papers and articles. His main interest is in grassland and wetland birds. He was also the Executive Editor of Journal of BNHS, and other BNHS publications.