Karanpura Must Live

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 37

No. 8,

August 2017

By Bulu Imam

As I recall it was no less dramatic when I walked across the Bachhra opencast coal mine between the quaint Anglo-Indian town of McCluskiegunj and Hendegir on the Damodar river in the shadow of the North Karanpura ranges with the elephant Tara and British travel writer, Mark Shand, at the end of the rainy season of 1987. Little did I know then that the North Karanpura Opencast Coalfields Project was going to be responsible for similar mines like this across my beloved valley of the Damodar river, where I had roamed since my boyhood days and later chased notorious rogue elephants.

One day as I was sitting in my office at my desk, my maternal uncle, Bishop George Saupin S. J., who was then Bishop of Hazaribagh and Daltongunj, tapped on my shoulder and said, “Laddie, have you heard about the North Karanpura opencast coal mines project?” I had just started the INTACH Chapter in Hazaribagh that year (1987). I soon learnt how relatives of a Jesuit priest in Hazaribagh had obtained information regarding coal in the Damodar river valley and through intermediaries, had engineered a deal between an Australian mining company and the government of India.

The discovery of coal in the Damodar valley, which divides the plateau of Jharkhand from east to west with Ranchi in the south and Hazaribagh in the north goes back to early British days in the 18th century. The region is a Gondwanan rift valley formation, layered by trough faulting along the Narmada-Sone fault. It is also a region of India’s richest sal forests and wildlife with tigers, elephants, leopards, gaur, and large herds of sambar and chital. At one time, even lions and cheetahs (Sanctuary Asia, Vol. XXXV No. 2, April 2014) had roamed here in what was South Bihar state before it was made the new tribal state of Jharkhand in 2000. Much earlier, 200 km. to the north, the lion capital of Ashoka had been erected near the capital of Patliputra. The area would reveal, after my subsequent searches, over one dozen painted rock shelters of the Meso-Chalcolithic period painted by prehistoric Protoaustric/Dravidian aborigines, who evolved into indigenous tribes living in the area today and who paint their mud-walled, tile-roofed houses with exactly the same animals and other designs as the sandstone painted rock-shelters. These people today are represented by the scheduled tribes Oraon, Munda, Santal, Birhor, Ganju, Turi, and scheduled artisan castes such as potters (kumhar), carpenters (rana), basket-makers (turi), oil extractors (teli) and agriculturists and weavers (jolha). In this tribal heartland amidst the then lush forests, the first coal mines were opened in 1851 in Giridih in the east followed by the Ranigunj and Jharia coal mines in 1885.

The Ashoka coal mine caused displacement of the Tana Bhagat sect of the Oraon tribe, some of whom are employed in the mines, while some are eking out a living by reclaiming land in the forests. Courtesy: Sanskriti Centre, Hazaribagh.

The Ashoka coal mine caused displacement of the Tana Bhagat sect of the Oraon tribe, some of whom are employed in the mines, while some are eking out a living by reclaiming land in the forests. Courtesy: Sanskriti Centre, Hazaribagh.

Mining Lies

Estimated to contain 40 billion tonnes of coal the Damodar valley (now called North Karanpura after a small village, which gave its name to the mega-mining project) was targeted for massive coal exploitation from the beginning of the 20th century. By 1985, the high technology turnkey mechanised coal mining project envisioning scores of mines was started between the Indian and Australian governments, signed with Whyte Industries of Sydney. The initial vision was to open 25 large opencast coal mines, displacing over 200 villages. The first mine called Piperwar was located at the western end of the valley near the Satpahar ranges, today famed for their Mesolithic rock paintings. Other mines such as Magadh, Amrapalli, Keridari, Punkri Barwadih, and Rautpara were to be executed by the Central Coalfields Ltd. (CCL), a subsidiary of Coal India. They claimed the mining would be benign, and that there would be no damage to the landscape, forests and villages, which would be rebuilt on a larger and better scale. CCL promised also that the mined areas would be in-filled after mining and then reafforested. I was then naïve enough to actually believe them! There was a sacred grove at what is today the eastern end of the Piperwar OCP, now a 25 sq. km. mine of over 90 m. depth. I enquired whether this sacred sal grove with its 300-year-old trees would be spared and was assured it would. Today, the area surrounding this mine is more than 75 sq. km. of barren excavated man-made valleys where virtually no living thing is found, let alone a sacred grove! The Piperwar mine was also a bone of contention for another reason other than the six villages that it destroyed. It was a forested wildlife corridor linking the Mahudi ranges of North Karanpura with the Palamau Tiger Reserve in the west. This corridor lay along the well-watered Damodar valley between McCluskiegunj and Balumath. These were the elephant and tiger corridors linking the Hazaribagh and Palamau jungles.

The notorious Greenfield mining claim was that after the existing landscape and forests were machine-dug to a depth of 100-120 m., the entire area would be filled in again and replanted with trees! Along with this massive lie is the contamination of water sources, with no proper means to contain the chemical pollution coming out of the mines and flowing uncontrolled into the rivers. Technically, there are supposed to be sedimentation ponds known as ‘tailing ponds’ to check water pollution, but the scale of the operation is far too large to control, particularly in the monsoon. The topsoil of the mined area is also very precious and technically supposed to be protected and preserved for the filling in but in fact these precious natural reserves just erode in gullies into the various streams, ending up finally in the Damodar river. The river becomes a channel for the chemical refuse of the mines, carrying tonnes of zinc, cadmium, arsenic, and other toxic chemicals, all the way to the Bay of Bengal.

The Damodar river has become a channel for chemical refuse of the mines, carrying tonnes of zinc, cadmium, arsenic and other dangerous chemicals ultimately down into the Bay of Bengal. Courtesy: Sanskriti Centre, Hazaribagh.

In the Piperwar mine, they fitted a kind of conveyor with tubs carrying the coal up to the washery at Mangaldaha a few kilometres away. We found a megalithic site in this place, one of many to be found in due course, and the natural and man-made arrangement was walled in to ‘protect’ its cultural heritage. This is lip-service, while the villages of the descendants of these people were being razed in the middle of the mining areas.

It was at about this time that I brought to light the six beautiful painted rock shelters of the Satpahar range about which so much has been written. They are the living forms of animals at rest and flight painted by the hand of Mesolithic man some dating as far back as ten thousand years according to rock art experts! Strange bedfellows indeed the mines and the rock art – but on second thought not so strange if we consider the Pilbara rock art being destroyed by mining in the Dampier archipelago in Western Australia! In 2005, Sacred Sites International (Berkeley) listed the North Karanpura rock art along with Pilbara as an endangered World Heritage Site. I worked on this recognition with Malcolm Turnbull, who is now the Prime Minister of Australia.

The coal washery of Mangaldaha near the river Damodar is only one of 18 such coal washeries, which pollute this river. When I had seen the Damodar in the 1960s as a young man, it was as clear as a Kashmir trout stream with a sandy, pebbled bed. Today, it is like a gorged black python of filth, which flows out of Jharkhand down into Bengal. Its fortune hangs heavy in my heart.

Fighting for the Damodar Valley

After my uncle George’s warning about the Karanpura project, I immediately organised a cycle rally of Young INTACH volunteers to cycle from McCluskiegunj at the foot of the Ranchi plateaus across the valley 60 km. to the Hazaribagh plateau. It is always the youth that rally to a call to protect their heritage, what will be theirs in the future! So, over a hundred of us set out from McCluskiegunj on the western end of the valley on a February morning in 1988. McCluskiegunj itself was in the eye of the storm since it had been chosen by the mining authorities for a railway siding to handle washed coal from the Mangaldaha washery! This 24-km. rail line through forests and adivasi lands and villages drew vociferous protests from the Tana Bhagat (an Oraon sect) who live in the thangi, which is a centre of the Satpahar rock art. This tribe worships in the rock-art caves!

The cycle rally/padyatra over three days and 60 km. led to a direct confrontation between myself, as INTACH Convener, and the Managers of the various CCL coal mines we passed through and where we lodged our protests. The matter gained the attention of the press and a great deal of notoriety. Atleast our voice was being heard!

Nalini D. Jayal, a former secretary of the Ministry of Environment, was then the Director of INTACH’s Natural Heritage Cell. In Tehri, Uttarakhand, the protests of Chipko against the Tehri dam led by Sunderlal Bahuguna was similar to ours. He visited Hazaribagh and the Valley twice and offered his support and was a great source of inspiration. Along with Nalini Jayal, Prodipto Roy of Council for Social Development (CSD) and INTACH organised the first seminar (of the many that would follow) titled ‘Environmental and Social Impact of Indian Coal Sector – North Karanpura Project’ at the India International Centre, New Delhi. Sunderlal Bahuguna formally launched Chipko in my home ‘Sanskriti’ in Hazaribagh in October 1989. In the same year, my mother Yvonne died and the void in my life was to be filled by two decades of steady campaigning. The flagship North Karanpura Campaign.org started in those years has now grown to include a staggering number of NGOs and non-profit organisations along the Damodar river fighting to protect it today! The then Australian Prime Minister had heard about our campaign and Mr. Keating conveyed his desire for a meeting with me through his ambassador in Delhi. I also met with First Secretary Dr. Mark Thomson whose help would be invaluable in setting up our now world famous Tribal Women Artists Cooperative, which was the figurehead of our campaign in 1993.

The tempo had already started building up in the campaign. Though I was inexperienced to understand such a large issue in all its complexities, I enjoyed the challenge. I was always a keen horseman and I knew “a horse must be given its head”. I was riding a thing that I hoped would lead to a successful conclusion without falling off! Amidst a rush of reports, interviews, seminars, television documentary films, and interactions with influential people such as Maneka Gandhi, our then Environment minister (who stopped the Tandwa TPS in the 1990s) taking interest, the unimaginable happened.

The Past Rescues the Future

In 1991, my old Jesuit friend Tony Herbert of the Australian mission in Hazaribagh was setting up his now famous night schools in the Barkagaon valley. He informed me about an Australian friend visiting the village Isco (i.e. actually ays in Sanskrit means a metal copper/iron and in Mundaric kho means a mine or cave) near an abandoned old iron/copper ore mine in the extreme eastern end of the valley in what was marked as the Rautpara Opencast Coal Project) who had spoken about a cave with strange painted signs in red haematite (or liquid iron ore). I had in my many interactions with the Australian engineers at Piperwar discussed the close resemblance of our brown village “pie” dogs, which I was then researching and comparing with the Australian dingo. This dog would become famous as the ‘Santal hound’ after a documentary film made by National Geographic (In Search of the First Dog) featured it. The film won the Explorer Club’s Award in 2005 in New York. I was talking of the possible connection between our tribals and Australian aborigines! My friends told me that similar research had proved the aborigines’ indigenous status on their lands and been of great advantage for establishing their land rights! The time was right as the drafting of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples had just begun in 1982 (though it would only be completed two decades later). I suddenly realised I was riding a tiger!

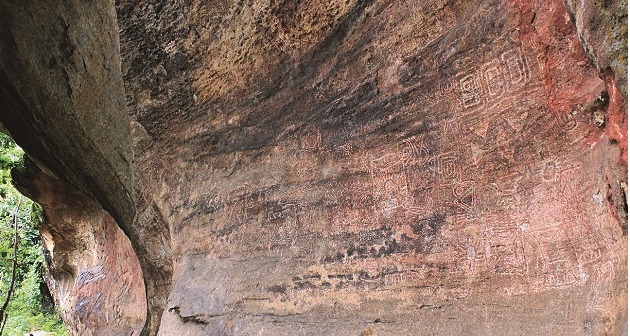

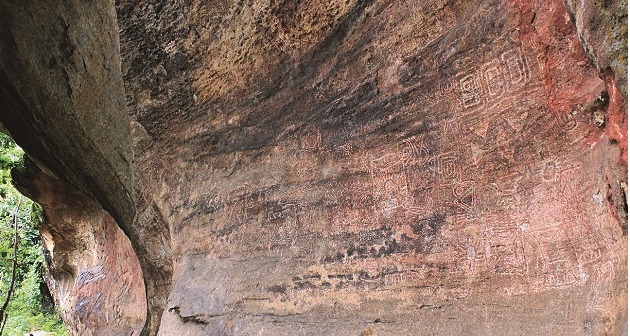

Dated between 4000 BP to 9000 BP, the rock art at Isco established the origin of man in India during the palaeolithic period in the valley. Courtesy: Sanskriti Centre, Hazaribagh.

Tony Herbert’s information completely transformed our focus. I first visited Isco in the spring of 1991 with my wife Philomena Tirkey, an Oraon tribal. I remember writing at that time, “My wife bent down to pick up some thing and handed me a civilisation.” The first man whom we met on that wild and rugged range of the Sati Hills in Isco was Khaita Munda, who for several years would be my guard at the Isco rock-art site. His ashes are, as I write, buried beneath a thorny bair tree in my garden. Khaita was a tall, heavily built, wild-looking man. He did not speak much, taking us up a long scarp of stony surface, which was the rising of the Isco stream with its little pools of water and the descent into the cave of forgotten dreams named locally Marwateri. From this eerily haunted place where we picked up the first tools of Early Man in the sand pool in the cave, we walked up and out of the underground cave through a series of openings, into the sunlit shelter of a great sandstone overhang painted with rock art that left all of us speechless. This was the final destination – we had found the adivasi’s indigenous title to their lands and which would open up a world we knew little of far from the confines of little Hazaribagh. Immediately after this, I formed a firm friendship with Julian Burger, the Director General of the United Nations Human Rights Centre in Geneva.

Later, professional archaeologists and rock-art experts and academics would come to certify that this finding was of the foremost palaeo-archaeological and rock-art site of Eastern India! After 30 years of research and filming and writing, we still have not completed the discovery of Isco. It has given Jharkhand the complete stone tool calendar of Early Man from the palaeolithic to the present (fortunately now preserved in my Sanskriti Museum in Hazaribagh). After cutting my son Justin’s 18th birthday cake in the Marwateri grotto, the visitors began to come. It was immediately visited by S. B. Ota, Director of the Archaeological Survey of India in 1993, followed by the great Austrian rock-art expert Erwin Neumayer of Vienna. Then an extensive list of national and international experts followed suit. Isco established the origin of man in India during the palaeolithic period in the Valley. The rock art was dated to the Meso (9000 BP) Chalcolithic (4000 BP).

A team from the Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts led by Dr. B. L. Mala and Bulu Imam (above) visit a rock-art site in the North Karanpura valley. The Tana Bhagats of Thethangi take part in a worship ritual at the Thethangi rock-art site in Satpahar range.Photo Courtesy: Sanskriti Centre, Hazaribagh.

I had my coordinates fixed. The rest was a matter of strategy. Like the Biblical David’s, my weapon was tiny, but it would prove to be good enough to take on the coal mining giants we faced. Most important was the moral argument of our activism about human rights, but I had another thing – or things – on my mind. Such as wildlife corridors, mandatory Environmental and Archaeological clearance, and of all things, climate change. The latter part of my campaign was tied to the mining of coal for industrial use. That we had our rights clearly established with proof of the indigenous status of the adivasis helped not a little by the finding of numerous Megalithic sites set up by the ancestors of the tribes and most likely of Ha and Munda origin. Their title to the land was in rock paintings, stone tools, megaliths… and it was a title recognised in the Declaration of Rights of Indigenous Peoples of the UN to which India was a signatory!

I had about this time also come to understand the true nature of coal as the prime cause of global warming and the threat of climate change through my friend Edward Goldsmith’s environmental journal The Ecologist. It was a strange turn of events, which came about with the help of friends such as Rachel Carson and Satish Kumar of Resurgence, John Papworth of Fourth World Review and Edward Goldsmith’s late son-in-law Mark Shand. The latter travelled with his elephant Tara to realise the true importance of the Valley as a corridor for wildlife including elephants and tigers. If the big opencast coal mines came in, it would mean the disruption of wildlife corridors of big mammals already on the Endangered Species List. I had, apart from the World Wildlife Fund, also the support of the IUCN (International Union for the Conservation of Nature).

Edward Goldsmith, to those who knew him, was not only a treasure trove of information but a friend to be trusted to his last breath. And I had his support. He immediately understood my request for a ground survey of elephant migratory corridors passing through the North Karanpura valley from Betla in Palamau in the west through Hazaribagh’s jungles to Bengal in the east, between Bokaro and Dalma Elephant Sanctuary. Divisional Forest Officer West Division Hazaribagh was my old friend Ehtisham Kazmi, IFS (He would later be the Director of the Betla Project Tiger National Park mentioned in Palamau). Ehtisham stood by my claim that the proposed Karanpura project opencast mines would destroy the elephant (and tiger) corridor with Palamau. He stood by his guns despite official harassment and I am proud to note that last year he received the Sanctuary Lifetime Achievement Award). The study would be done by my son Justin, which would later set the format for the recognition of similar elephant corridors by the Wildlife Trust of India (around 90 to date!). These years were the mid-1990s and the funding of Rs. 5,000 (then a grand sum) was through the kind offices of Edward Goldsmith sent by the U.K. Ecological Foundation whose Patron was Queen Elizabeth.

A Change for the Even Better

1996. Enters my Hazaribagh home, a tall Englishman of Quaker heritage, an expert whitewater canoeing and open sea kayaking expert, whose principal interest was the tiger corridors between North Karanpura and Bundelkhand in Madhya Pradesh, with special regard to a large World Bank loan to Coal India. He had an agenda and he was writing for major Canadian environmental journals like Borealis. His expertise and logic lay with his acute understanding (and unraveling of World Bank loans and Coal India’s habits, i.e. using resettlement and rehabilitation funds for mining extensions, in this case into the heart of Madhya Pradesh in Singrauli). You can imagine my canvas: Rock art and palae-oarchaeology, indigenous rights, wildlife corridors, tribal art… It was a heady mix!

Justin and I, in the company of well-known geologist and sociologist Kuntala Lahiri-Dutt, placed on December 15, 1995, the first elephant wildlife corridors study in India before the First World Mining Environment Congress at La Meridien, New Delhi, chaired by Shri. Kamal Nath, then Union Minister for Environment who was already an admirer of our fledgling work. In the presence of national and international delegates he immediately ordered a comprehensive multi-disciplinary study of the Elephant Migratory Corridors of the North Karanpura valley! CISMHE (Centre for Interdisciplinary Studies of Mountain and Hill Environments), Delhi University was commissioned to do the study. This major report, which took a couple years to complete was shredded by a subsequent government but not before someone had smuggled out a xerox copy. It brought out the truth and though it never became the law, it paved the way for over 90 elephant corridor studies by the Wildlife Trust of India!

The key to the North Karanpura campaign entered the lock of political decision-making in a very strange way. Philomena and I were leaving with our artists and family for Sydney for a one-month tribal art painting project commissioned by the Australian Museum. President Bill Clinton was going to visit Ranthambhore Tiger Sanctuary. Tiger-man Valmik Thapar of TIGER-LINK (of which I was a member) would hand him a letter when he was guiding him round Ranthambhore on March 19th. Thus emerged the famous letter to President Clinton drafted by others including Phil Carter and Bittu Sahgal with regard to the World Bank Funding to Coal India, which was abetting destruction of wild tiger and elephant corridors in North Karanpura! It was signed by among others Bittu Sahgal, Jamshyd Godrej (President WWF-I), Debi Goenka (Bombay Environmental Action Group), Daphne Wysham (Institute for Policy Studies, Washington DC), Andrea Durbin (Friends of the Earth, USA), Dana Clark (Center for International Environmental Law, USA), Bill Hare (Greenpeace, Netherlands), Peter Jackson (Chairman, Cat Specialist Group, World Conservation Union –IUCN), Peter Richardson, Environmental Investigation Agency, U.K.), Edward Goldsmith, The Ecologist), Richard Harkinson (Minewatch Collective, U.K.), and James Arvanitakis, AID-WATCH -Australia). All hell was about to break loose. And it did.

James Wolfensohn was then the President of the World Bank. He was a friend of Teddy Goldsmith but he did not write to me solely because of that. His sympathy lay in a fact which later arose when Daphne Wysham steered the North Karanpura Campaign into the U.S. Senate through her Institute for Policy Studies in Washington DC. The World Bank Loan to Coal India was cancelled and thousands of employees received what I was told is called “the golden handshake” which means premature retirement!

On our return from Australia in the summer of 2000, Philomena and our eldest daughter Juliet presented a Statement before the Special Rappoteur on behalf of TWAC and our indigenous people on the North Karanpura mining displacement at the 19th and 20th Sessions of the UNWGIP (United Nations Working Group on Indigenous Peoples) in July 2001 and 2002 at Geneva. This was followed by my son Justin’s intervention at the same forum in the next session, when he was representing DOCIP (Documentation Centre for Indigenous Peoples, Geneva). Note was taken of our claim for the application of the (draft) Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, which would only be finalised later.

Later I would make an appeal for the North Karanpura ranges and valley of the Damodar to be declared a Biosphere Reserve by UNESCO, but by then rampant mining had begun. Mandatory Archaeological and Environment clearance was accepted but in fact not ever implemented. The Tribal Women Artists Cooperative (TWAC) carried the banner of our campaign to 17 important art exhibitions in Australia. In 2000, I had televised interviews regarding mining at major talk shows in Sydney and I am grateful to John Kirkman of the Australian Museum for his help in making the Tribal Art a campaign module. Later we would hold over 37 art exhibitions in major galleries in Europe and England (Rebecca Hossack Gallery - London, SOAS-Brunei Gallery - London) and state museums (Pigorini Museum, Rome, five State Museums in Australia, Canada, Swedenand the U.K.), which would make Karanpura a household name in many small villages such as in Austria where I started with help from FIAN the Danube to Damodar Campaign, which is still alive! So, in this way the struggle goes on even as we now learn that the present government is putting a stop to coal mining and turning to renewables for energy. The Greenpeace report ‘Coal Mines Trashing Tigerland’ which was based on my campaign in North Karanpura, however met the axe from the government. Whichever way I look at it the time spent and the ties made across the world through this unique ‘art for environment’ campaign have proved successful and a model for future campaigns.

With the present government putting a stop to coal mining and turning to renewables for energy, the author and his wife Phiilomina (right) hope that the western North Karanpura valley will look as it once did before mining interests pillaged it. Photo Courtesy: Sanskriti Centre, Hazaribagh.

Rock Art

The rock paintings found at the Karanpura valley represent some of the oldest palaeo-archaeological sites in the region. This means that the cave dwellers who made the paintings belonged to autochthonous societies living here before agriculture caused a shift to the first primitive villages. Researchers from around the world have visited the valley to study its ethnographic and rock art heritage. The Indira Gandhi National Centre for Arts (IGNCA) documented it with a high-resolution video/photography for the List of World Rock Art in 2007 put together by Japan. One of the unique features of the living traditions of the rock art is that even now the Tana Bhagat sect of the Oraon tribe worship at these sites. The sect has been impacted and displaced by the coal mines of Piperwar and Ashoka and the railway lines of the washeries and coal sidings. They have still not been given the lands taken away by the British and promised to be returned by the Indian government. Some of them are employed in the mines but they have lost their agricultural land and are eking out a living by reclaiming land in the forests.

Wildlife Corridors and Painted Houses

The Damodar river receives over 40 tributary streams in its wide forested valley interspersed with a dozen hill ranges such as the Sati, Aswa, Mahudi, Satpahar, Bundu and Hazaribagh. In the midst of these are the densely forested sal corridors, which have provided conduits of food and water to elephants and tigers to traverse a hundred kilometres from east to west without being obstructed by human habitation. In 1985, a nefarious opencast coal mining project called the North Karanpura Coalfields Project provided mechanised turnkey technology to create several dozen open cast coal mines, destroying several dozen villages and wiping out agriculture in a region known as the ‘rice bowl’. Displacement of tribals has also led to the destruction of their artisan culture, agriculture and rock art in the hills and palaeo-archaeology sites, which affirm the presence of their ancient ancestors and give them indigenous status under the United Nations Declaration of Rights of Indigenous Peoples. Their houses are often painted with images of forests and wildlife, perhaps a continuation of the prehistoric rock art in the hills.

_C.jpg)

The indigenous tribes living in the forest corridors of North Karanpura paint their mud-walled, tile-roofed houses (above) with the same animals and designs on the sandstone rock-shelters as did the prehistoric Protoaustric/Dravidian aborigines. Tragically many must earn a livelihood today by making and selling coking coal. Photo Courtesy: Sanskriti Centre, Hazaribagh.

An unpolluted strech of the upper Damodar river between McCluskiegunj and Balumath. This well-watered valley was a wildife corridor linking the Hazaribagh and Palamau jungles before the construction of the Piperwar mine.

Author: Bulu Imam

The Ashoka coal mine caused displacement of the Tana Bhagat sect of the Oraon tribe, some of whom are employed in the mines, while some are eking out a living by reclaiming land in the forests. Courtesy: Sanskriti Centre, Hazaribagh.

The Ashoka coal mine caused displacement of the Tana Bhagat sect of the Oraon tribe, some of whom are employed in the mines, while some are eking out a living by reclaiming land in the forests. Courtesy: Sanskriti Centre, Hazaribagh.

_C.jpg)