Meet Billy Arjan Singh

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 20

No. 9,

September 2000

Born in Gorakhpur on August 15, 1917, three decades before India's Independence, the feisty 'Billy' Arjan Singh is a man ahead of his time. His ancestors found favour in the court of Queen Victoria and he is a living legend today; considered by some to be the very soul of the Indian tiger. Unpopular for having helped put 26 shikar companies out of business 40 years ago, his life has been mired in controversy ever since he reintroduced Tara, a hybrid, zoo-born tigress into the wilds of Dudhwa. The forest department insists that the cat had to be shot as a man-eater; but Billy insists that Tara's progeny are still doing well. Living now at Tiger Haven, wilderness he saved from the press of agriculture, he angrily castigates his critics in the forest department, accusing them of being both ignorant and incompetent. He met Bittu Sahgal last month and spoke of his love affair with and hopes for Panthera tigris.

Body-builder, reformed hunter, foster-father to an infamous tiger, or a thorn in the side of the Uttar Pradesh Forest Department… how would you like to be remembered?

I want simply to be remembered as Arjan Singh, a man who loved tigers and fought to keep them alive and safe from humans.

But I recall with great pleasure my days of weightlifting and body-building, when I was able to meet the American and Russian Olympic weightlifting teams and managed to lift 220 pounds in the Clean and Press; close to a record for my weight!

You once threatened to wrestle Dr. Sálim Ali during an Indian Board for Wildlife meeting years ago, if my sources are right?

He was such a delightful man, with a great sense of fun. When he and I stood next to each other, we looked quite a sight. Someone at the IBWL meeting had commented on his frail body and how it contrasted with my pumped-up muscles, so I caught Sálim by the neck in a mock grip and he asked if I would care to fight. Everyone had a good laugh, including Sálim.

Like Sálim Ali you were also once a shikari.

No. I can't lay claim to be a shikari. At least they had some rules. I was a bloodthirsty, murderous urchin who shot anything that moved. Even as I grew older I continued to shoot owlets and hyaenas and leopards and tigers. I am condemned to live with my deepest regrets for being part of the slaughter that maligned the evolutionary processes that created such magnificent creatures. I finally stopped shooting in 1960 when I was overcome with remorse for ending the life of a beautiful leopard in the headlights of my jeep. I had no right whatsoever to destroy what I could not create.

But you did eventually work to have sport hunting banned in India?

Yes. I realised when the tiger was slipping away from us that sport hunting was a sinful, hypocritical act opposed to all civilised human thought. No one has the right to be entertained by murder. Sadly the virus of sport killing runs deep in the human psyche and wild predators like wolves, tigers, leopards and sharks continue to pay the price for human blood lust that condones killing with the use of telescopic sights, automatic weapons and even helicopters. Yes, I took on the outfitters of the day. They tried every dirty trick in the book to coerce the Indian government to let them carry on their bloody business when tiger shikar was banned in 1969-70. They spoke sanctimoniously then about conservation, but took extra money for guaranteed kills. I recall that Allwyn Cooper actually set up a dead leopard for the famous African hunter Robert Ruark to shoot when they could not deliver a live animal in his line of fire! They were an unscrupulous lot and India is well rid of them.

Let's talk about Dudhwa. How did this forest become so entwined with your life?

Well, I had taken to farming in the area soon after Independence when I left the army. The thunder of barasingha hooves was commonplace. I had to struggle to establish my farm over the years, but despite the trials and tribulations I came to love it all the more for its proximity to the wilderness. Once, with my brother Balram and a friend called John Withnell, we shot two barasingha at Bhadi Tal, only to discover that they were a protected species. We promptly reported ourselves to the Divisional Forest Officer, who let us off, complimenting us for our honesty in confessing our mistake. I was a pioneer settler, but as the years passed, farmers began to migrate in large numbers from Pakistan. When a large company called The Collective Farms and Forests Ltd. cleared 10,000 acres, I could see the writing on the wall and began to seek a halt to the destruction.

When did Tiger Haven come into your life?

That was in the height of summer in May 1959. I had gone out into the forest on Bhagwan Piari, the elephant with whom I spent 25 wonderful years. I could see the Himalayan ranges across the Dudhwa grasslands. At the confluence of the Soheli and Neora rivers I discovered a patch of land that was owned by a politician who had lost all interest in it. I bought it and turned it into a functioning farm, which was inundated several times a year when the rivers were in spate, but which profited greatly from the fertile silt that was left behind. Here we protected wildlife, even as we managed to share a functioning farm.

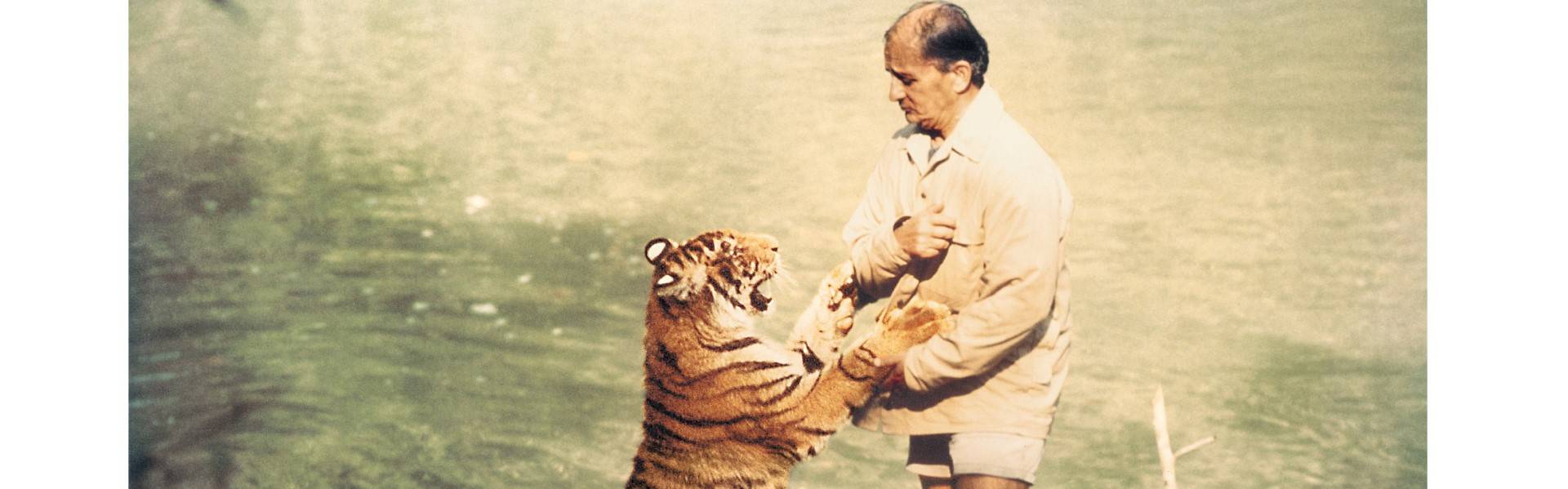

Photo courtesy: Billy Arjan Singh.

Photo courtesy: Billy Arjan Singh.

Shooting was still the rage, though you had stopped by then.

True, but along with several friends we used to reserve the shooting blocks adjacent to Tiger Haven to stop others from using them. Sometimes I used to fudge applications in five or six different names! One way or another we managed to provide a safe haven for wildlife. I was repaying old debts. Some old shikaris used to come and drink with me around my campfire and their loosened tongues would provide me with information that I would unhesitatingly use against them!

Was this why you were appointed to the U.P. State Wildlife Board?

Yes, that was in 1964, the same year the U.P. State Wildlife Board itself was established. I remember George Schaller had come to visit me at Tiger Haven and together we conducted a survey in the adjoining Ghola forest, only to discover that the presumed 1,500 barasingha had dropped to 600. I then submitted a proposal to protect the endangered barasingha and after some vacillation, Dudhwa became a sanctuary that shared a border with Nepal. And best of all, Tiger Haven was right in the middle of it. I created grasslands, salt licks and water sources to attract barasingha, which I also helped drive with help from Bhagwan Piari, beaters and crackers all the way from Ghola. Had we not done this, they would have succumbed to guns and land grabbers operating under the protection of Naxalites. Tiger Haven's protection plan had worked. I could ask for nothing better.

And what did your neighbouring farmers have to say about all this?

They were upset, as was the hunting lobby. But that was their problem. The tiger and the deer on which they depended were safe. Nothing else mattered. Years later, in 1972, I also managed to get the Kishanpur Sanctuary declared. By then the Wildlife (Protection) Act had also been declared, Project Tiger was on the anvil and, thanks to the late Mrs. Indira Gandhi, the tide had begun to turn in favour of India's wildlife.

In India wildlife is the responsibility of the forest department, yet your own relationship with them has always been rocky. Why?

They could not tolerate my calling a spade a spade. I was always against their commercial timber operations. I also recall when the tigers of Dudhwa were in their deepest crisis that the forest department lied to the world, stating that there were 104 tigers in the park. I knew that there were no more than 20! And when tiger carcasses were turning up in wells and canals, it was somehow suggested that overcrowding was driving them to suicide! The forest department doesn't care about tigers. They are only concerned with absolving themselves on file of any and all blame for the tiger's desperate plight.

But surely you cannot hold them solely responsible for the tiger's decline?

I suppose not solely responsible. But their spine was certainly conspicuous by its absence when, for instance, they conspired to allow the Irrigation Department to construct a barrage along the Soheli river, which formed the boundary of Dudhwa, which had by then been declared a national park. I had pointed out that the barasingha for whom the area was protected would be badly affected. Not one person in the forest department supported my plea for protection and the barrage, illegal as it was, was built. Later they compounded the damage by constructing safety walls. In the Madrahia-Sathiana area, the barasingha numbers dropped from 1,200-1,600 to just about 150. It was a catastrophe. Of course I hold the forest department responsible.

What is the problem, the root problem for tigers?

Habitat fragmentation. This is what induced a division of one species into eight subspecies. In conjunction with poaching, habitat loss has devastated the tigers and has led to three subspecies vanishing altogether. Then, of course, is the problem of people competing with the tiger for survival. As the master race, we have to resolve this conflict or Armageddon will overtake our overpopulated and plundered universe. We are losing our forests and the symbolic presence of the animals it shelters before our eyes.

Photo courtesy: Billy Arjan Singh.

Photo courtesy: Billy Arjan Singh.

And you feel not enough is being done to counter this decline...?

Look, even the figures presented by the forest departments of the total number of tigers alive in India are suspect. The estimation is carried out by untrained personnel, haphazardly selected from subordinate staff who must perform a host of other forestry operations. Wildlife staff are transferable to five different disciplines and two-thirds of all tigers do not even have this minimal protection. Certainly not enough is being done to save them.

What would you have the government do?

Stop the fragmentation of tiger habitats immediately. Have uniform control over tiger habitats, rather than the differentiated administrative control that is the rule today. The forest department is trained in commercial forestry, but saving tigers is a totally different discipline for when a tree is destroyed, habitat is lost. "A clean forest floor" is the dream of a forester, but it is the nightmare of a wildlifer. The same department cannot and should not run the operations for they are antagonistic. Our government's budgetary allocations are not only minimal but dishonestly structured. Despite our reverence for Ganesha and Durga, political and administrative will to conserve wildlife is infinitesimal. That is what I would have the government change.

And what about Tara? You would agree that she has been the root of most of your antagonism with officialdom?

I suppose so. The project that allowed me to reintroduce Tara, the tigress into Dudhwa was approved by no less than Mrs. Indira Gandhi. Tara conceived a total of nine off- spring over a period of 15 years and I believe that they have reinvigorated the Dudhwa tiger population. European scientists however claimed that Tara was an Indo-Siberian hybrid and suggested physical elimination on the grounds of genetic pollution. The attitude to wildlife protection by officialdom is not only uncaring, but demeaning.

But almost every expert would advice against the "genetic pollution" of wild tigers.

Research suggests that subspecific integration may not be injurious. Hybridisation is revitalising. And the tigers of Dudhwa continue to breed well. Project Tiger refuses to accept that genetic depression is the final arbiter of survival. I find this obsession with purity strange. When the main religion of the country forbids intergenetic alliances for purposes of lineal purity we connive at continuous incestuous breeding of tigers in facilities like Nandankanan. India must accept heterozygosity for tigers or we cannot save the species. Let's just say that my differences with the forest department are irreconcilable.

But even your worst critics respect you and no one questions your purity of purpose in wanting the tiger saved. As a WWF gold medal winner, member of IUCN's Cat Specialist Group, Honorary Wildlife Warden and recipient of the Padmashree, surely you can mend your fences with people who share common objectives?

I am too old now to change my spots. I do not trust them and they do not trust me. I have never claimed to be infallible, but I know what tigers need to survive and in ndia today the right to survival is being denied to them. I believe that the future of the great cats lies in the creation of maximised reservations.

But translocation of a large predator in a thickly populated country does seem unrealistic and your own experiments with leopards have proven fatal for some unfortunate victims.

People who live near wild animals risk death. Many people die at the hands of "untranslocated" great cats each year. Translocation is going to be an inevitable strategy. When I pass to another world, you must remind people of this conviction of mine. It was right for rhinos in Dudhwa and it is right for tigers too.

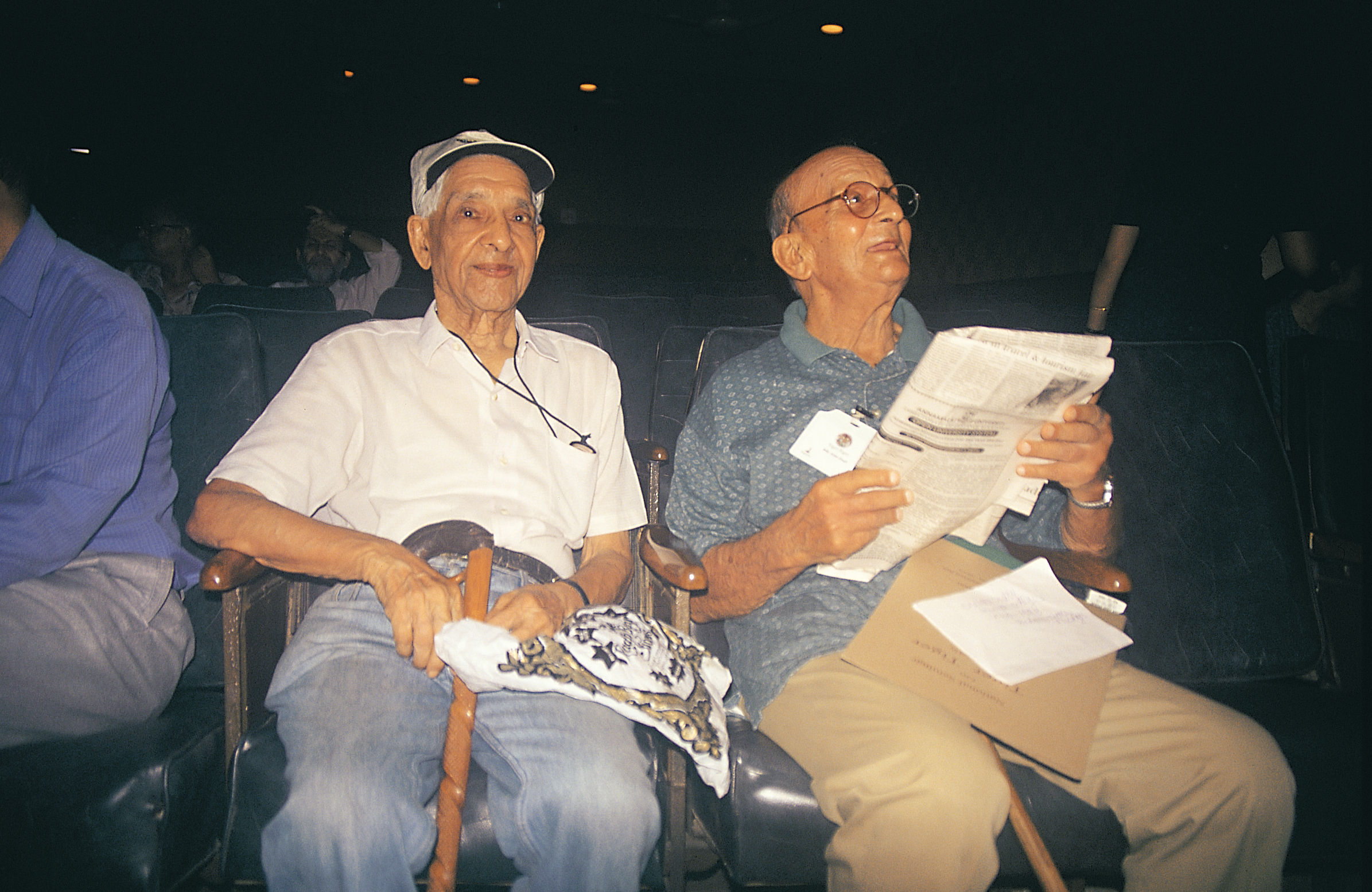

Photo: Bittu Sahgal.

Photo: Bittu Sahgal.

And how do you suggest this objective be accomplished?

The most workable solution is to translocate animals from other (overcrowded) areas. We could artificially inseminate a receptive wild tigress. Or we could reintroduce a captive born cub as I did.

Has your life been a success or a failure?

Life is a continuum. Success or failure can only be judged in millennia. Tara's bones lie in some deep ravine somewhere in Dudhwa. Her cubs are alive and well. That gives me a sense of fulfillment. But Dudhwa is an island and desperately needs to be connected to nearby forests. The many poachers, the timber mafia and the ham-handed officials that operate unfettered, mock the very thought of "success".

And your last word about the tiger?

The air we breathe and the water we drink stem from the biodiversity of the universal environment and its economics. The tiger is at the centre of this truth. If it goes, we go.