Meet Koustubh Sharma

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 37

No. 6,

June 2017

A Senior Regional Ecologist with the Snow Leopard Trust, Koustubh Sharma has worked in some of the remotest and toughest terrains in the world - where his work is contributing to a greater understanding of snow leopard ecology. He speaks with Lakshmy Raman about his current work involving policymakers, conservationists and organisations from snow leopard range countries and why he believes that building capacity and training local researchers and conservationists is the best way to secure the long-term future of the ‘grey ghost.

What first got you interested in snow leopards?

Their sheer elusiveness! Despite several attempts to study them over the years, little was (is still) known about these cats. This is perhaps due to their evolutionary advantage of being able to melt into and occupy mountainous and tough terrain, and breathe in inhospitably thin air! My fascination for technology and its applications to reduce the evolutionary gap between humans and snow leopards was perhaps the main driver that got me hooked on to snow leopards.

Who inspired you on this path?

I have been fortunate to have had some of the greatest mentors including my parents who never forced me into becoming an ‘engineer or a doctor. The person who introduced me to snow leopards was Dr. Raghu Chundawat, considered one of the pioneers of snow leopard studies. I worked with him when he was studying tigers in the Panna Tiger Reserve. His stories and photos from Ladakh, Xinjiang (China) and Sarychat (Kyrgyzstan) fascinated me. I also owe thanks to Dr. Asad Rahmani for his faith in me that I would be able to study, despite my background in Physics, the four-horned antelope, another difficult-to-spot species.He trusted me on a five-year doctorate project in the Panna Tiger Reserve. Even before that in 1993, had it not been for Giridhar Kinhal and Manoj Misra, two forest officers from the Madhya Pradesh cadre, who organised a nature camp in the Churna, Satpura Tiger Reserve, I would have never experienced the bliss of being in the wilderness.

Photo: Snow Leopard Trust/Snow Leopard Foundation-Kyrgyzstan/State Agency for Environment Protection and Forestry.

Photo: Snow Leopard Trust/Snow Leopard Foundation-Kyrgyzstan/State Agency for Environment Protection and Forestry.

Tell me about your most memorable encounter in the wild… was it seeing a snow leopard?

In 10 years, I have seen the cat in the wild twice. Yes, thats how elusive they are! Apart from these two sightings, there is one incident that I remember fondly. Our team had just radio-collared the first adult female snow leopard for our long-term research project in South Gobi, Mongolia. We had nearly abandoned the site to set up snares as we were worried that the goats of a local herder, Gana, who could not move to another pasture, would trip the snares repeatedly. Gana, however, encouraged us to stay, and show him the snares so he could keep his goats away. As luck would have it, there was a snow leopard in the snare the same night. Once Orjan, our field biologist and the lead researcher on the telemetry project, had tranquilised the cat, we invited Gana to join us. Despite it being one in the morning, he joined us at the capture site within 10 minutes. This was the first time he was seeing a snow leopard despite living amidst them. We asked him to name the cat! Touching her gingerly, he took a few seconds and suggested ‘Khashaa, meaning Jade in Mongolian. It was also his daughters name! After collaring and releasing the cat, the next evening when Orjan went to reset his snares, he found some money tucked under a rock. Gana had left an offering to the mountain gods for the well-being of Khashaa, though we never asked which one! The overwhelming emotions of this episode make it my most memorable field story until today.

What was your first project?

My first project was to look for a site that potentially had enough snow leopards to initiate the first ever long-term study on the species. Nine years since, the project is still running strong with more than 23 cats collared and unprecedented data from camera trapping over nine years providing us with a never-before-acquired insight into their population, behaviour, movements, dispersal, birthing and mortality!

Today you are a Senior Regional Ecologist with the Snow Leopard Trust - tell us about your journey.

It has been a wonderful journey. Apart from having spent time in some of the most pristine habitats across Asia, I have been fortunate to be part of teams that are contributing to our understanding of snow leopard ecology. One of the most rewarding aspects is gaining friends from various parts of the globe. I firmly believe that even the best scientists doing field research or analysis of data, cannot replace what local researchers and conservationists can achieve. Apart from conducting primary research, the focus of my work has been on building capacity and providing training that can bridge the gap between developments in research and analytical techniques, and their implementation in the field.

What are you currently working on?

I am currently devoting much of my time to the Global Snow Leopard and Ecosystem Protection Programme that brings together governments from 12 snow leopard range countries, policymakers, institutions, organisations and conservationists toward securing the future of snow leopards and their mountains. While the task of coordinating a programme of this scale is monumental, it has huge potential to secure the future of snow leopards and their mountain ecosystems. Although non-government organisations are working to successfully implement research and community-based conservation programmes, they perhaps may never be able to scale it up to the level that governments can. Going by an equation in Physics, where work done = mass x displacement, even if the government attempts a few positive steps, the impact will be enormous. The purpose of this programme is to provide scalability to the several conservation and research programmes that have been piloted and implemented elsewhere.

I am also working on analyses and interpretation of our camera trapping and genetic sampling data. This will help improve the inferences that we can make from such datasets. Surprisingly, despite the many years of research, we still have data from systematic sampling of snow leopard populations from less than two per cent of its entire range. We hope to use the advancements in technology and statistics in the past one decade to improve our ability to estimate populations of endangered species such as the snow leopard with more confidence and rigour.

Photo: Teri Akin.

Photo: Teri Akin.

What would you say is the most pressing issue you face as a cat/mammal biologist today?

The most crucial aspect of working with wildlife, especially elusive predators, is that of engaging with people, whether it is local communities, frontline staff of Protected Areas, experts, officials, politicians or corporates. Everyone brings valuable expertise, knowledge and a viewpoint. It is not surprising that most innovations and developments in the field of wildlife research and conservation have come from effective collaborations and partnerships between experts and stakeholders from various cross-cutting streams.

What are the key challenges facing the snow leopard?

While some of the threats to these cats have remained unchanged, we also have several emerging threats. For instance, poorly-planned infrastructure and mining in snow leopard habitats is directly impacting this elusive feline. This cat represents an ecosystem that plays a vital role in the water supply for more than a billion people and is among the most sensitive to climate change. Not only is the changing weather regime and vegetation a key challenge, these also amplify conventional threats such as decline in prey and rise in human-wildlife conflict. Given, the remoteness of the locations, studying and developing conservation strategies is not easy.

So climate change could spell doom for the snow leopard.

It surely can. The real challenge of climate change, as I mentioned before, is how it will exacerbate existing threats. For instance, people moving closer to snow leopard habitats in search of pastures for their livestock can result in more conflict. Whats worse is that with greater uncertainty, intensity and frequency of extreme events, be it flash floods, dzud (severe winter), landslides or lack of food and water, locals will have to face the brunt of it. This, in turn, may affect their tolerance to human-wildlife conflicts. It will also require a huge amount of additional resources to support communities during these events.

Talking about conflict, habitat degradation due to livestock grazing is a huge problem.

Livestock grazing is moving further into snow leopard habitats due to climate change and this is changing the seasonality and productivity of mountain pastures. There are some successful models such as grazing free reserves that are currently being set up in many parts of the Indian Himalaya. Additionally, in many parts of the snow leopards range, nomadism is the way of life. In fact, families that choose to opt out of nomadic patterns are declared outcasts by the community. Nomadism is actually a great means to prevent over-exploitation so long as the livestock populations do not exceed a certain threshold. Apart from promoting alternate livelihoods, better management and protection of livestock and crops, and insuring against occasional losses are some of the strategies being used to reduce human-wildlife conflict.

Photo: Pranav Trivedi.

Photo: Pranav Trivedi.

Poaching too threatens the snow leopard…

Yes, poaching continues to be a challenge. In the past one year, we have seen a surge in the number of reports and confiscations. Whether this is due to better policing or represents a true increase in demand and supply in the illegal markets will only be revealed with time and diligent analysis of data. What we do need is a systematic database and unified effort to monitor and control illegal poaching and wildlife trade.

Research cameras set up by local citizen scientists near the source of the Mekong river captured images of snow leopards and common leopards using the same habitat. How will this impact the future of the species?

To capture snow leopards and leopards on the same camera was a remarkable discovery. Although there have been instances earlier where common leopard and even tigers have been recorded at altitudes that snow leopards inhabit, this was the first time we recorded common leopards and snow leopards in the same camera. Of course, lack of proof is not evidence that such overlaps did not occur earlier. An absence of evidence cannot be considered as an evidence of absence. What is required is more systematic research to understand future changes, if any, in the distribution patterns of the species.

Tell us about the Global Snow Leopard Summit.

In 2013, the President of Kyrgyz Republic convened a forum for snow leopard conservation that was attended by governments of all snow leopard range countries. Supported by most organisations and institutions working towards conservation of Asias high mountain ecosystems, the forum resulted in country governments endorsing the Bishkek Declaration for Snow Leopard Conservation. This spawned the Global Snow Leopard and Ecosystem Protection Programme (GSLEP) with a goal to secure at least 20 snow leopard landscapes by 2020. The Summit (International Snow Leopard and Ecosystem Conservation Forum) is being organised at the mid-point of the programme to take stock, influence policy and mobilise resources to implement the GSLEP programme successfully across the range countries.

What do you hope to achieve through the Summit?

The aim of the forum is to attract and expand the understanding of political, scientific and economic leaders and the masses to the issues of governance, conservation and economic development in Asias high-mountain habitats. We hope to bolster high-level political will through adaptation of policy-level recommendations for country governments, and create innovative financial mechanisms to support research and conservation in the ecosystems where snow leopards live.

Snow-leopard conservation programmes in Spiti and Ladakh have been focusing on community education and awareness programmes. Are these making a difference?

Definitely. None of these programmes are standalone, and are in fact integrated into each other. It is the people who are at the centre of all conservation action. People who live in the last remaining natural areas, whose lives depend on these ecosystems, and who are most affected by policies and actions designed to protect biodiversity. It is imperative for us to gain their support, and this recognition is at the heart of the GSLEP Programme.

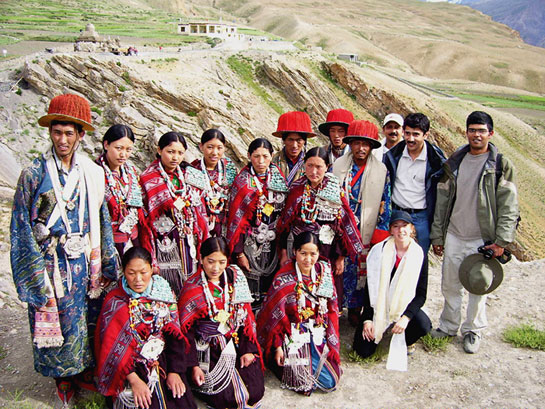

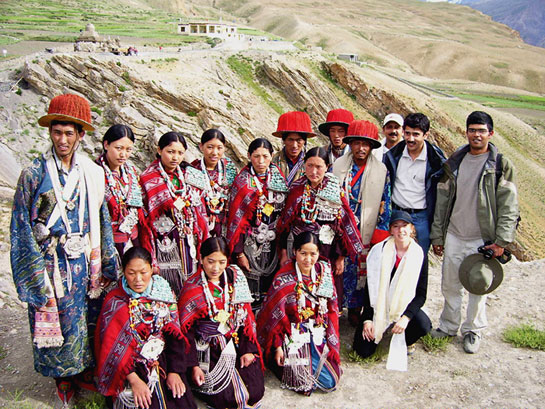

Photo: Yash Veer Bhatnagar.

Photo: Yash Veer Bhatnagar.

What would your message be to the leaders of India?

India is rich, it has been rich for several millennia. Just a simple quantification of the ecosystem services that the mountains and forests provide to her population will run into several times Indias per capita income. Development of people in the poorest parts of the country is important, and it can be achieved without employing ecologically-destructive development models. This approach is also in sync with the ancient Indian value system that identifies human beings as part of an ecosystem and not above it. The GSLEP Programme draws several parallels from the already-operational Project Snow Leopard, which attempts to change the paradigm of wildlife conservation by partnering with all stakeholders, be it communities, scientists or various departments within governments. What the world needs today, and India perhaps needs it even more, given the proportion of the population that is vulnerable to adverse impacts of climate change, is an ecologically-sensitive development plan that does not compromise on the long-term well-being of people.

Are you hopeful about the future?

Absolutely! The fact that 12 snow leopard range countries have come together, and are talking about snow leopards is a sign that conservation of mountain ecosystems is becoming a mainstream issue. The younger generation is the other reason why I am so hopeful. I have seen a close colleagues now eight-year-old son Shivi grow from an infant naturalist into a passionate birdwatcher, who just could not contain the excitement of seeing a wild snow leopard during a recent trip to Spiti. I see my two-year-old daughter Tanayaas delight on seeing any living being, be it a spider or a tiger. I recently also interacted with a class of six and seven year olds from across the globe, and their curiosity and enthusiasm about wildlife was no different. If our ruthless education and professional systems don't wipe away the curiosity of these beautiful minds, we are sure to have a better future for people and wilderness alike.

(First published in: Sanctuary Asia, Vol. XXXVII No. 6, June 2017.)