Meet Usha Lachungpa

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 42

No. 4,

April 2022

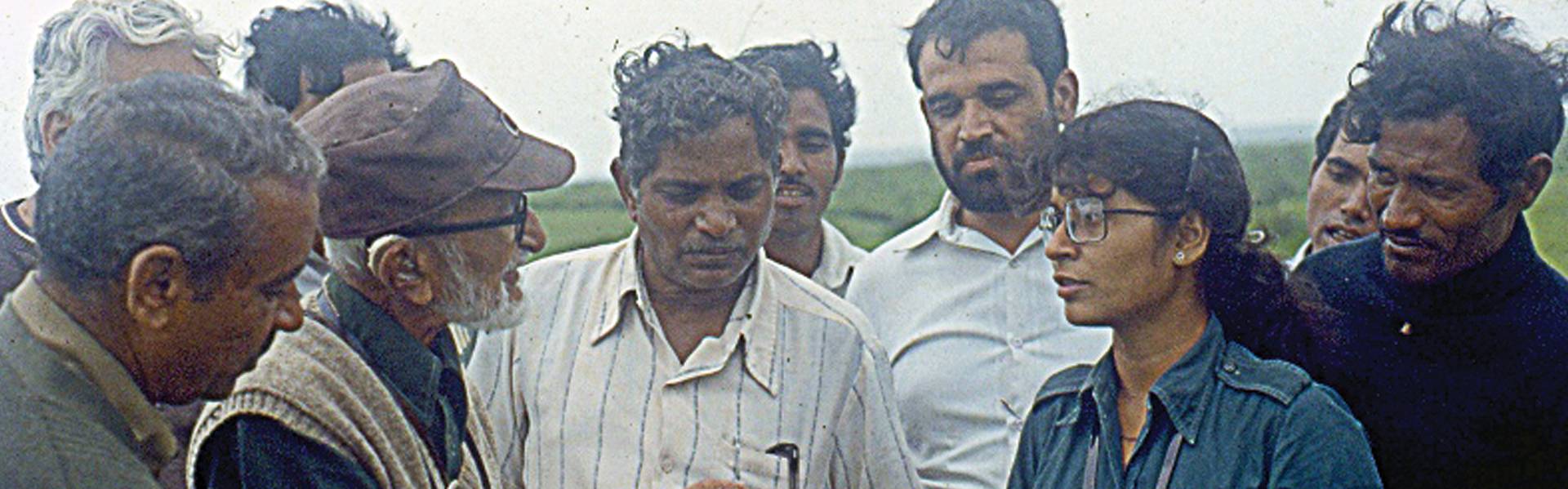

A passionate wildlifer and perseverant optimist, Usha Lachungpa has lived a life in service of nature. Growing up in Mumbai, she went on to become a vital member of the Bombay Natural History Society (BNHS), and thereafter moved to the Sikkim Himalaya, blazing the way for women in conservation to follow. Senior Editor Abinaya Kalyanasundaram spent time with the Sanctuary Wildlife Service 2021 Awardee, and her family, which includes three dogs, speaking about wildlife conservation, her days at the BNHS, and the spirited challenges and joys of her life.

Over the last four decades, Usha Lachungpa has woven strong and lasting links between the state government and NGOs in Sikkim to the advantage of biodiversity protection of this state. Photo: Prachi Galange.

What led you down this beautiful path?

It all started when I joined the BNHS when I was in Class 12 around 40 years ago, when the atmosphere was citizen-science oriented. People from all ages, professions and backgrounds would come together and we would go on nature trails and bird monitoring walks. I got to explore the real world of natural history then – a really wonderful experience, especially for a city kid! These trips ingrained in us a love for nature. I also worked at the BNHS office in the bird room, which has a large collection of birds. I was required to check the labels on these birds, most of which were written by Dr. Sálim Ali. He had the most amazing handwriting I’ve ever seen. I used to practice copying it sometimes. I had a small table as well, in an alcove next to Humayun Abdulali, who has done so much for conservation in India. He worked with such unshakeable devotion. I also had a chance to work closely with several conservationists like J.C. Daniel who was a great mentor to me.

That sounds incredible! Tell us about your first visit to Sikkim.

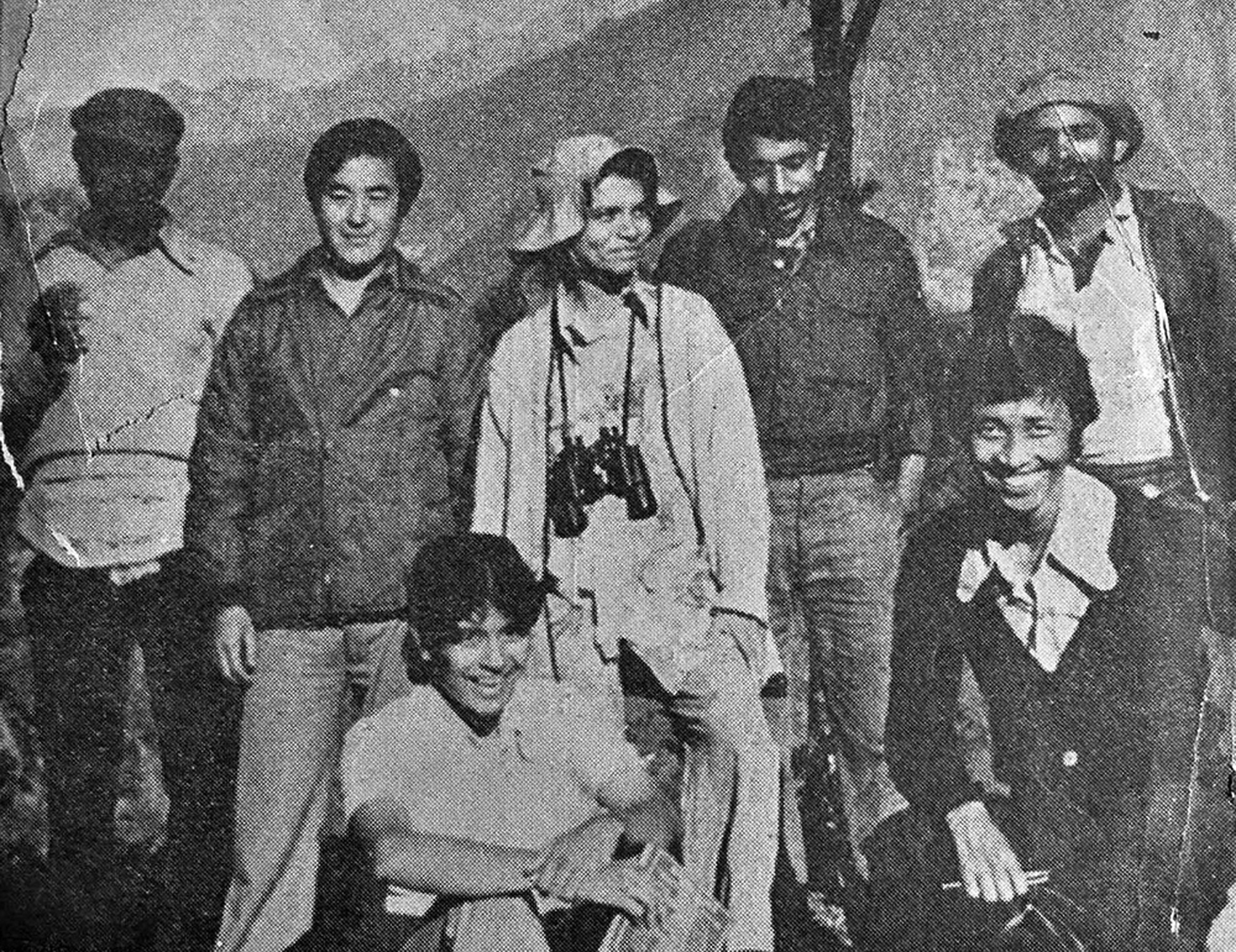

In October 1980, before I joined college for a Masters in Zoology (Physiology and Biochemistry), six of us from BNHS embarked on a month-long expedition to Sikkim. I was beyond excited. My mother even stitched a canvas rucksack from scratch for me. On arriving in Gangtok, the DFO assigned three people to accompany us for a trek in West Sikkim, in the Khangchendzonga National Park; the trail popularly known as the Dzongri trek. It was a beautiful experience! I still remember vividly the sight of a huge Blood Pheasant flock, and of three male Monal Pheasants diving off the side of a cliff, their rainbow feathers iridescent in the light. I also remember how cold it was. I used to sleep with my shoes on inside my sleeping bag! We also took a trip to explore North Sikkim.

In October 1980, Usha Lachungpa travelled on a BNHS expedition to Sikkim for the first time. This trip changed the course of her life forever. Clockwise: Marcelin Almeida, Karma Lepcha, Arati Kaikini, Manek Mistry, Ulhas Rane, Tashi Tshering, and Usha. Photo Courtesy: Meena Haribal.

This was also when you first met your husband, Ganden.

Yes, Ganden had just finished college and had joined the Forest Department for a short while. He had accompanied us on the expedition. Manek Mistry from our group and he became good friends. Back in Mumbai, one day as I was returning home from college, I decided to take the train instead of my regular bus. Walking towards the Churchgate station, I was surprised to see Manek and Ganden walking out of the subway! Manek had apparently invited Ganden to work in Mumbai at a company, manufacturing ‘Aristocrat’ brand of suitcases. Eventually, Ganden began accompanying our group on our weekend trips. And our friendship grew over the years. We eventually got married in 1983, a month before the BNHS Centenary.

Your association with BNHS only grew stronger after you graduated.

Yes, BNHS was like my second home. I would spend most of my time there apart from classes. In fact, my mother would get upset when I gave people my BNHS phone number instead of mine!

Tell us more about your work with the BNHS’s Bird Ringing projects.

My first bird ringing experience was at Point Calimere, Tamil Nadu as a volunteer member with a BNHS Nature Camp. After I completed my M.Sc., J.C. Daniel sent me to the Hydrobiology Project in Bharatpur. This was before it became the Keoladeo National Park. It was a dream landscape for someone interested in birds. We were working with Mirshikar and Sahni bird trappers. These former poachers were adept at capturing birds without hurting them and had been roped into BNHS by Dr. Sálim Ali. They could track and capture hundreds of birds in a night, with Mirshikars using tools like flaming torches and drums – a unique light and sound technique. One of these trackers, Ali Hussain, became a great friend, and in the mornings, we would sit with our data sheets, weighing scales and rulers. Ali – with no ‘formal education’ – would place his hand inside the basket, identify the bird often with its scientific name, before even taking it out, and we’d measure, weigh, ring and release it. He had a knack of handling birds and keeping them at ease – birds are delicate and sometimes can just stop breathing when stressed. We used aluminium alloy rings with BNHS numbers. The project’s purpose was to study migration. Now, with advanced technology such as GPS and satellite tracking, it is even more interesting and you can see the exact routes they fly on, where they halt, why they are zipping around in a certain area, and so on. Some birds weigh just a few grams but fly incredibly long distances, following ancient routes that no one taught them about... it is truly magical!

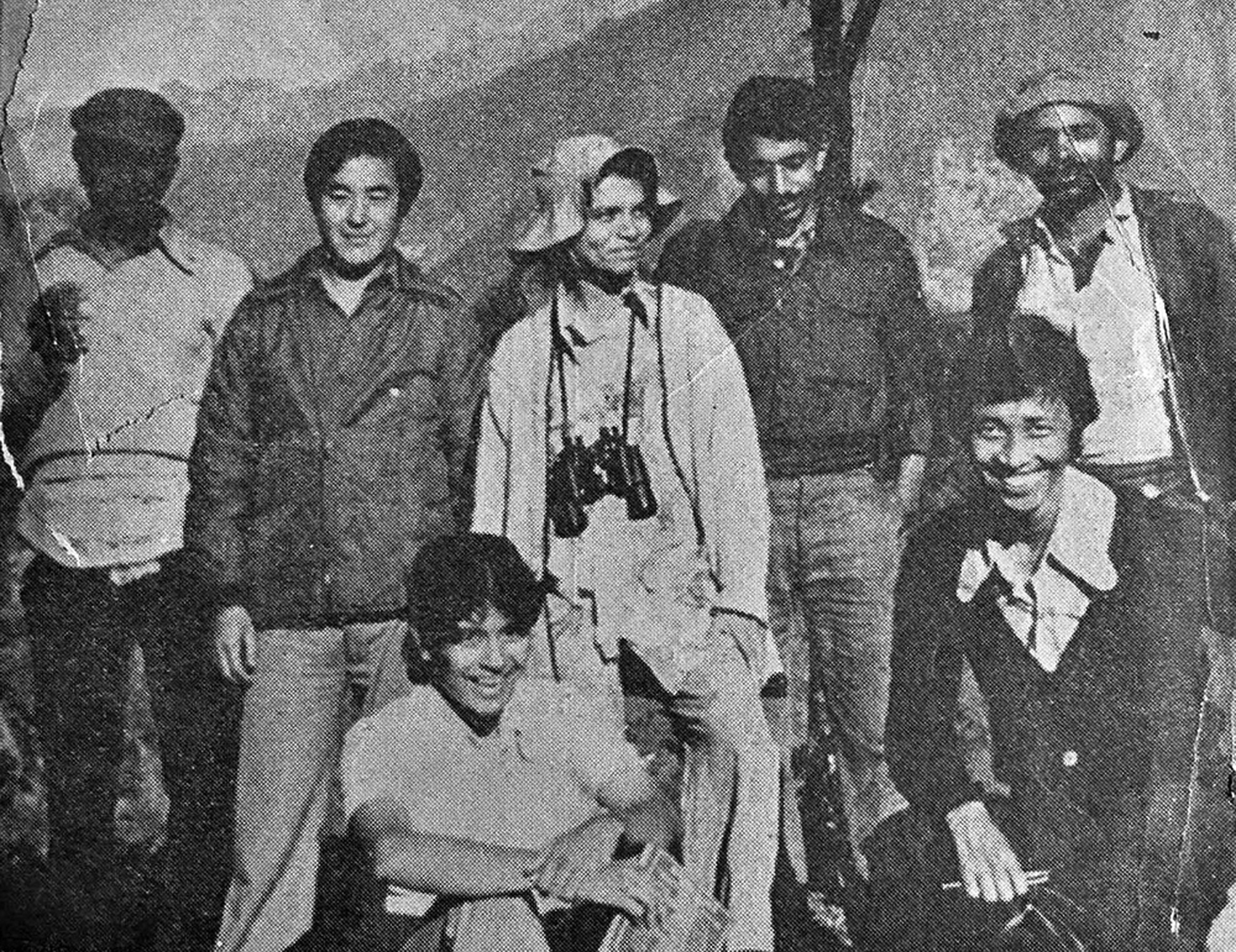

Between 1984-86, Lachungpa worked with Dr. Asad Rahmani, studying Lesser Floricans in Sailana, Madhya Pradesh. Using grass hides, they would wait and observe the males display, noting down behaviour and jumps. Photo Courtesy: Dr. Asad Rahmani.

You also worked on Lesser Floricans across India.

Yes, though Bharatpur was a beautiful place, it wasn’t overall a good experience for me. I did much field work, but under stressful conditions and would have given up but for Vibhu Prakash, (well known today for his work on raptors and vultures) who helped me. I was then reassigned to work with Dr. Asad Rahmani in the Endangered Species project, which was a huge relief. I learnt so much from Dr. Rahmani, an amazing scientist and passionate conservationist. We studied Lesser Floricans in Sailana, a huge grassland landscape in Madhya Pradesh using grass hides near the fields, sitting inside for hours at a time, watching the beautiful display of the males through our binoculars – noting down their behaviour, the time between jumps and the number of jumps! We recorded female floricans preferring nearby soyabean fields. I also remember the delicious maize our cook would specially roast for me, right in the field, not too far from my hide! My most memorable moment was when we tagged our first Lesser Florican, for which Dr. Sálim Ali himself came and ringed the bird! We studied the floricans to see if we can solve the mystery of where they disappear after the breeding season. We also surveyed potential Lesser Florican habitats outside Protected Areas, such as reserve forests with grassland patches, or degraded forests. At that time, we looked for them in Gujarat, Rajasthan, Maharashtra, Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, Orissa, and a few more states.

We also did a Bengal Florican survey across the northern belt, from Uttar Pradesh to Assam. We met stalwarts like Billy Arjan Singh, S. Deb Roy, Joanna Van Gruisen and others. We sat atop machans and rode on elephant backs, because it is easier to look above the elephant grass for displaying floricans. That year, Ganden also joined me. It was a memorable time. In 1983 we were married, and in 1984 we were travelling virtually across the country’s natural habitats looking for Lesser and Bengal Floricans.

How did your move to Sikkim come about?

I wanted to raise my family in the mountains, and so, we shifted to Sikkim toward the end of 1985 when we were expecting our first child. The people were nice, the place was beautiful, the mountains were serene. I have always felt that people are healthier in the mountains.

Usha Lachungpa seen with Dr. Sálim Ali (second from left) on the day they tagged their first Lesser Florican as part of the Endangered Species Project in 1984. Photo Courtesy: Dr. Asad Rahmani.

And you promptly joined the Forest Department of Sikkim.

No, it was in fact a strange story. After we shifted to Sikkim, we began looking for jobs and I wanted to continue working on wildlife and conservation issues like I had in the BNHS. So Ganden borrowed a typewriter from a cousin, and I typed out a proposal for the creation of a research wing in the Forest Department and my application for a post in that proposed wing! J.C. Daniel had given me a good reference letter. I was surprised to get the appointment letter at the same time our first daughter Minla was born! Everything happened at the right time. I joined in October 1986, when she was about four months old.

Your daughters are named after birds!

Yes. In fact, my mother-in-law predicted I would have three daughters, so I looked up names in my copy of Sálim Ali’s bird book and settled on Minla, Yuhina and Sibia even before they were born! We had two daughters and my dear friend Lima Rosalind named her own daughter Sibya.

Sikkim must have been a whole different place then.

Yes, it was so green and pristine. I saw there was great scope for research here. I began with the Asian Waterfowl Count, which allowed me to explore the high-altitude lakes across Sikkim. During each visit, I recorded many birds – like Ruddy Shelducks with chicks (at that time they were known to only breed in Ladakh). So I promptly wrote a note for the BNHS journal about it. Next time it was Ospreys, then Black-necked Grebes – also new records for Sikkim. On each visit, there was something new to be found. Like the Kaiser-i-Hind butterfly; or a host of cold desert species. My immediate boss W.T. Lucksom, the Conservator in-charge of the Wildlife Circle, noticed my passion and urged me to apply to the IFS. But as I was more keen on wildlife research, he sent my application for the Wildlife Institute of India’s diploma course, where I found myself the first woman student. I met some amazing people like Dr. A.J.T. Johnsingh, Dr. G.S. Rawat, B.C. Choudhury, V.B. Savarkar, Dr. Allan Rodgers, besides many others. I started off as a Project Officer working in the Wildlife Department and retired as a Principal Chief Research Officer of the Forest, Environment and Wildlife Management Department after 31 years.

I also wrote articles for newspapers like The Weekend Review, Sikkim Express, and quite a few others. These included notes on the last Tibetan mastiff, the dying Dokpas of North Sikkim, and a ‘singing’ tree in Gangtok where sparrows roosted. I did radio programmes, and conducted awareness programmes on conservation and wildlife for schools, the army, and other organisations. I also helped establish two experimental butterfly parks. It was very fulfilling and the department supported my passion as I was working from my heart.

You became a member of the Sikkim Biodiversity Board...

The Sikkim Biodiversity Board was started in 2006, and I shouldered the responsibility to revive and promote it. We showcased one-species-per-day in the local media throughout the International Year of Biodiversity in 2010 and were the only state to do so! I am now a Board Member. We worked at village and Gram Panchayat levels to record and document our biodiversity and encourage locals to have a stake in its conservation, especially if they could get fair and equitable shares of their bio-resources... things like crops, fruits, fodder, ferns, orchids, medicinal plants, grains, livestock, trees, even pests and weeds. Biodiversity Management Committees (BMCs) have been set up in every Gram Panchayat Unit (GPU). Many GPUs have now written their biodiversity registers – and as Sikkim is a small area, there is a lot of overlap in species across places, which makes it easy but also confusing. We technically vet the data sheets and this also helps in preventing biopiracy. In most states, the Biodiversity Boards are under the Forest Department, and it ends up not being top priority. Foresters get saddled with multiple portfolios, making their job difficult. So we tried to ease their work by involving local field foresters in the process. But states where the Biodiversity Board is not under the Forest Department have done much better, like in Goa. By law, the Board has to be an autonomous institution by an Act of Parliament. In many states, the Forest Department is saddled with it, despite lack of funds, staff and expertise.

A Great Crested Grebe and a Tibetan sand fox in the cold desert region of Sikkim. Photo: Pema Thinley.

A Great Crested Grebe and a Tibetan sand fox in the cold desert region of Sikkim. Photo: Pema Thinley.

Of your many wonderful experiences, what would you consider your most adventurous?

There are many! But what comes to mind right now is a recce I did to the Sebu La (pass) in North Sikkim, a year prior to an expedition with scientists from the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh (RBGE). It was to be a month-long expedition to understand the landscape better. The Sonam Gyatso Mountaineering Institute, Gangtok, where I often gave trainings on high altitude biodiversity, generously assigned me three of their instructors. They taught me where to buy rations from, how to pack and so on. This was in 1995! We hired a few yaks and porters. And I also called in Ali Hussain so we could ring some birds along that route. It was a phenomenally adventurous trek – Lachen-Thangu-Lashar-Sebu La – Yumesamdong – Tembawa Glacier – Dongkia La, Tso Lhamo Cold desert... it was virtually unexplored scientifically until then. Even J.D.Hooker, the prominent British explorer who wrote the Himalayan Journals, hadn’t explored this part!

It was beyond beautiful. When you cross over from the Lachen valley to Lachung valley, over the Sebu La, you will literally be straddling the pass. We even used an ice pick for climbing at one point. Once over the pass, we came out into Yumesamdong where there are some hot springs and where we could rescue five bharal or blue sheep. Then we climbed up to Dongkia La, the pass that overlooks the Tso Lhamo lake on the Tibetan plateau. On climbing down to the lake, we found we had run out of food, so we pitched camp and made soup from some wild weeds.

We carried mist nets, bird rings and data sheets throughout the trip. Ali Hussain used his expertise to observe the area and decide where best to set up the nets. That’s another thing I learned from BNHS, the value of local traditional knowledge is something scientists many a times fail to recognise and value.

You also have a plant named after you!

Yes, the scientists from the RBGE – Dr. David Lang, a retired veterinary surgeon and orchid specialist, Dr. Henry Noltie, a grass specialist among other flora and Dr. David Long, a moss specialist – were incredible. I kept thinking, this is how research should be conducted – with passion, specialisation and a supportive organisation. I learned a lot from them. Henry discovered a new species of grass at the base of Yulekhangtsa glacier during this expedition, and named it after me! Agrostis ushae. I was thrilled and humbled.

While on a 1996 expedition with the Royal Botanical Garden Edinburg (RBGE), a scientist Usha was accompanying, Dr. Henry Noltie, discovered a new species of grass at the base of Yulekhangtsa glacier. He named it Agrostis ushae in honour of her contributions to the state’s biodiversity. Photo Courtesy: Norbu Sherpa, BSI-Gangtok.

You also took part in the 1990 expedition by the Department to Green Lake and Zemu Glacier.

Yes! The expedition was to go to trans-Himalayan Muguthang, trek down to Green Lake, reach the Zemu glacier and head to Lachen. During this time, I was expecting my second baby, and did not disclose it, so I would not miss the chance! Apart from a couple of colleagues, no one suspected anything. After getting the go-ahead from my doctor and my ever-supportive husband, there was no holding back. I managed well, despite some nausea at the smell of mustard oil, and a strangely restricted diet. Yuhina, my second daughter, was born hale and hearty a few months later! What an experience! My child has crossed quite a few high altitude passes, scaled or slid down some of the steepest slopes, crossed icy rivulets and negotiated huge boulder laden valleys, and she didn’t even know it. Sudizong Lucksom, a great forester and an indigenous tribal Lepcha artist who so easily made beautiful hand-drawn works of art on Sikkim’s orchids, was also a part of this memorable expedition.

A rescued Black-necked Grebe and two Blood Pheasants. Usha Lachungpa’s extensive surveys across the state resulted in a book she co-authored – The Important Bird Areas of Sikkim. Photo: Usha Lachungpa.

Over three decades working with the Forest Department must not have been easy…

There have been struggles. I have pushed relentlessly for many issues, and people have told me to just let things go. But Sikkim is so precious, I couldn’t give up and I tried to explain and be persistent without being aggressive. Many senior officials understood this. I have tried my best to save Gurudongmar Tso (see page 91) and Gyam Tsona, two great lakes in the cold desert and sources of our Teesta (also Tista) river. There is also the satisfaction of adding a few new records of species for the state – I feel a sense of relief when I hear younger foresters and others echo the issues I tried highlighting, like the increasing garbage, free-ranging dogs hunting wildlife and livestock, invasive species... Small victories, choosing my battles and not giving up – that was my 31 years.

How much has the state’s environment changed in these years?

There has been much loss in the spaces, for sure. Roadways have been built into remote regions… for instance, in the Lhonak valley towards Muguthang. According to the Botanical Survey of India, there were 40 different ground orchid species along the route from Thangu, where we now see settlements of road maintenance workers. While Sikkim does have the best network of Protected Areas in the country – with the World Heritage Site status of Khangchendzonga National Park, Alpine and Rhododendron sanctuaries, even a small Conservation Reserve in South Sikkim – there are no PAs in the cold desert, which harbours mega fauna like the Tibetan wild ass, Tibetan argali, Tibetan wolf, Tibetan sand fox, snow leopard, Eurasian Lynx, Pallas’s cat, Himalayan marmot, woolly hare, and birds like the Black-necked Crane, Golden Eagle, Tibetan Snowcock, varieties of migratory waterfowl – all sharing space with domesticated species like yaks, and also defence areas, which are only expanding because of defence priorities. There is always the looming threat of diseases like Foot and Mouth Disease (FMD) brought in by ‘meat-on-hoof’ supplies. Increasing heavy vehicular traffic puts such load on the fragile landscape that landslides are a way of life now. This massively affects the tourism industry on which the state also heavily depends.

Another area that desperately requires more attention are the lowland forests of Sikkim, as they are most threatened on account of major infrastructure projects such as pharmaceutical companies, the fallout from the many hydro projects, urbanisation, increasing road networks and pollution. Many natural springs have been observed to have dried up. The Dhara Vikas Programme under the Rural Management and Development Department is mapping natural springs. The only way to ensure our long term water security is by protecting the forest tops and watersheds as well. The Fambong Lho Wildlife Sanctuary opposite Gangtok is still in existence only because it is the main source of water for all the villages around its base.

There are also the many hydropower projects on the Teesta…

I wish I had another lifetime to just see the river NOT die. The Teesta is the lifeline of Sikkim. And we are just letting it die? And the kind of fish biodiversity it has – 50 species in the two rivers of Sikkim, Teesta and Rangit – is astounding, and new species await discovery! What will happen once the dams are built and the gates are closed – where will the fish breed? Nowadays, you can buy exotic fish like red-bellied pacu, a relative of the piranha in the market, all bred outside Sikkim instead of the local fish, whose population seems to be affected by the effluents of pharmaceutical industries entering the rivers. A sad irony is that despite the many hydropower projects, Sikkim still faces regular power cuts. If Sikkim really has this much potential, then the power generated should light up our own state first, and it would benefit the state more if local communities ran them, with only the excess power sold for profit. Instead, we see these big agencies coming in and experimenting in this seismic zone V Himalaya region and very limited local capacity built up.

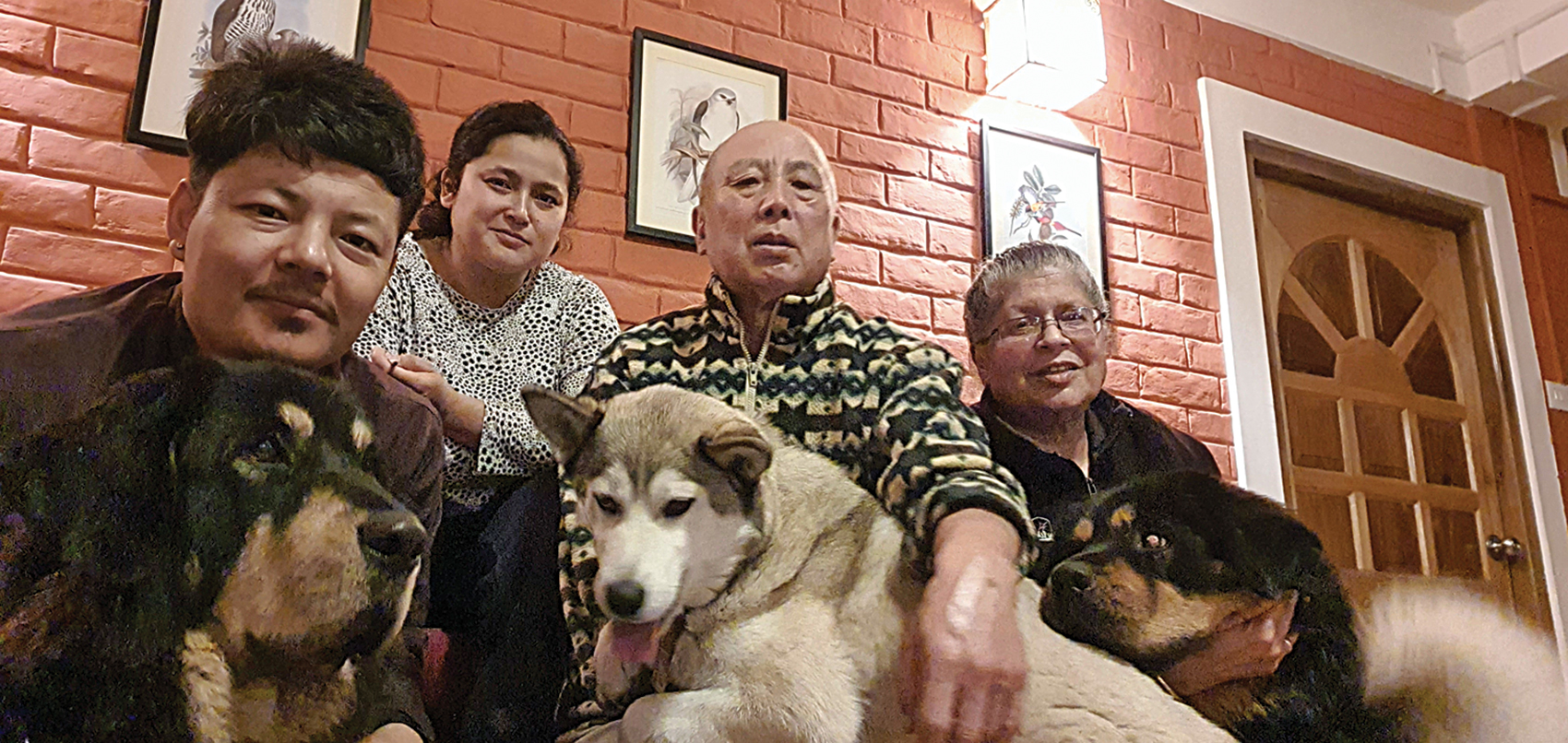

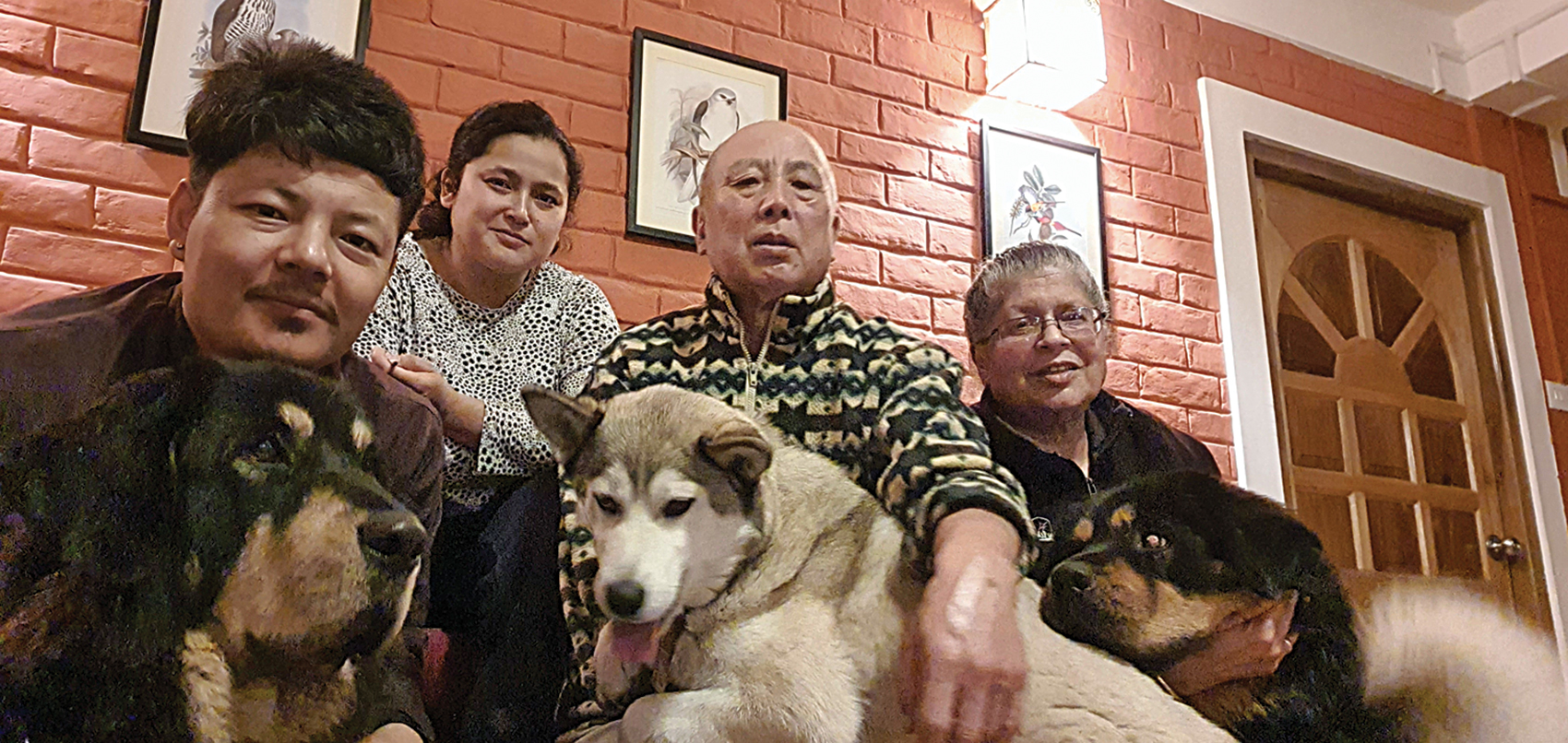

Usha with her family – (from left to right) son-in-law Karma, daughter Minla, husband Ganden with their pets, a Tibetan mastiff Leia (from Princess Leia of Star Wars), a half huskyWamo (meaning Tibetan fox) and another Tibetan mastiff Dhokbu (meaning Keeper of the Forest). Photo Courtesy: Minla Zangmu.

A word of advice for our generation?

Everyone should be involved in conservation, whether architects, engineers or homemakers. In my time, it was easier if you had a science background. Often I find that people from other backgrounds have more capacity and passion to learn more. Most birders and people doing studies here are not scientists – some may not even have a college background. And the younger generation is lucky in that you can see all the terrible things our generation has done, and you are able to fearlessly voice your discontent and you have the whole world in front of you. You don’t need to do big things, but everything you do counts. The important thing is to not give up – to not be disheartened. Keep at it. Try to enjoy the small successes around you – celebrate them with vigour.