Narmada The Soul Of India

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 20

No. 4,

April 2000

By Rainer Horig

It is hot and the river looks inviting. Ignoring Sunderlal’s dire warnings, I dive into the cool, blue-green waters that envelope me like a salve. Like millions of others, I celebrate the simple joys on offer; sweet water, cool air and a tranquillity denied to those who exhaust their lives in urbania. At this time of the year the river is still deep, but indolent. As I come up for air after what I promise myself will be my last dive, I sense a presence somewhere close to me. As the fear of the unknown overtakes me, I look 360 degrees around to discover two gulpy eyes staring at me less than 20 m. away. A tingle goes down my spine, even as my common sense tells me not to panic. Any jerky movements, I know, would communicate precisely the wrong signals to the crocodile whose space I had invaded! Gently, but purposefully, therefore, I head back to the safety of the shore, where, heart racing and legs wobbling, I collapse with sheer relief on the bank. Never again will I doubt Sunderlal. I know I was in no danger, but I am unlikely, nevertheless, to go out swimming alone in the Narmada’s deep womb.

Photo:Rainer Horig

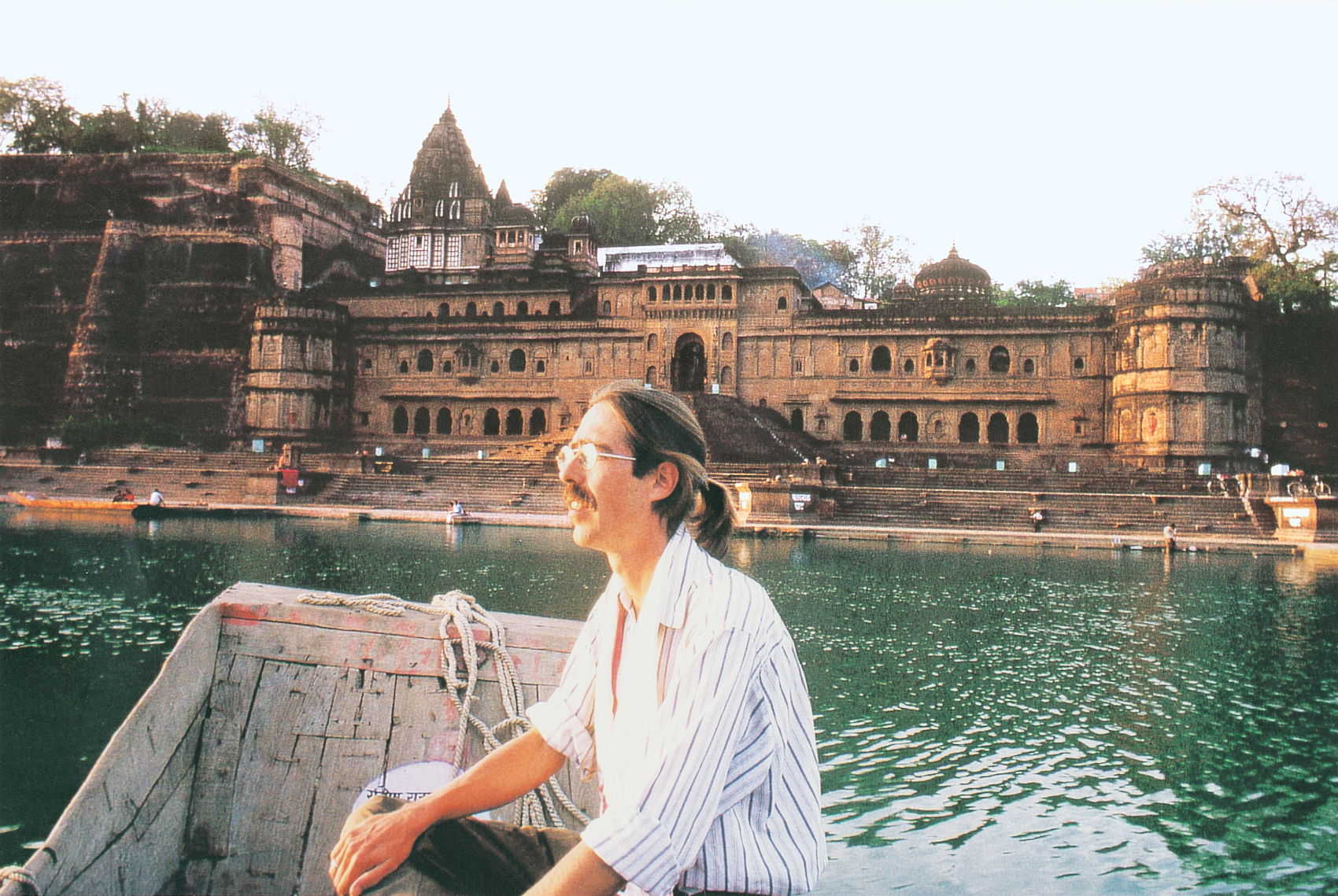

A living river

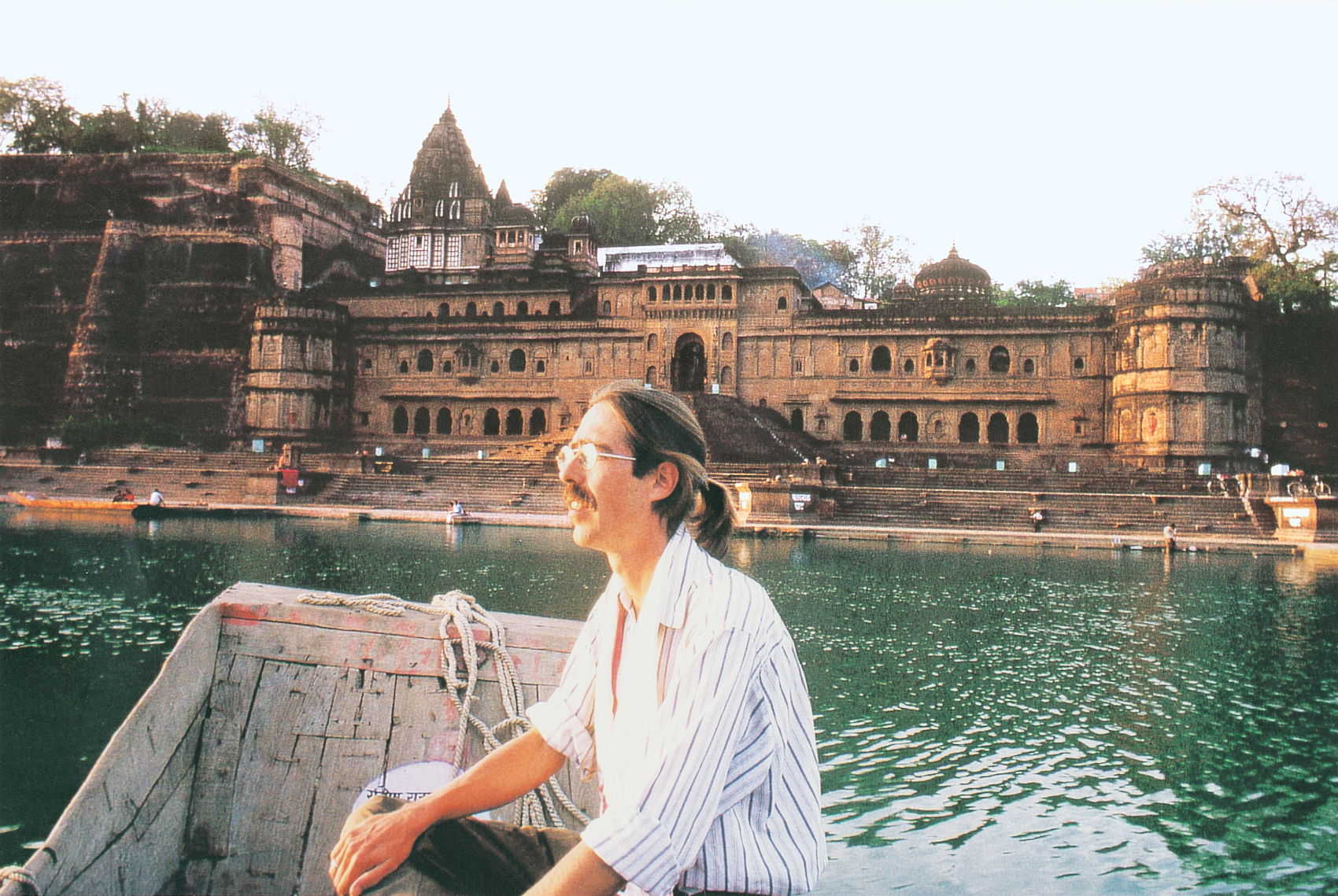

I was in Omkareshwar, a sleepy town less than a hundred kilometres southeast of Indore, one of the most famous pilgrimage sites along the famous Narmada river. Like a natural citadel, this temple-crowned island rises more than 30 m. from the tranquil waters. A great admirer of India, I cast my gaze along the ancient ruins and massive gateways that hint at the bustling town that Omkareshwar must have been in the past.

I sat awhile at the bathing ghat. I was in no hurry. It was here, just a few days ago, as I sat admiring the towering cliffs that line the bank of the river, that I befriended Sunderlal Kevat, a local boatman. While rowing me about in his shaky dugout canoe, he narrated wondrous tales of life and the fables that surround this, one of India’s holiest rivers. On hearing the tale of my ‘encounter’ with one of the earth’s most ancient reptiles, Sunderlal casually demonstrated how local fishermen routinely drive away the huge beasts they regularly came across. Carefully looking to ensure I was paying attention, he beat the water surface with cupped hands creating a sound that carried quite a distance.

“Some thirty years ago, when I was a boy, there used to be lots of wildlife here,” he said, puffing on his ever-present beedi. “In my village we used to spot wild boar and deer every day. Tigers used to come to the river to drink. But all that has changed. These days strangers who come to steal timber have frightened the animals away. They have stolen the life from a living river.”

The Narmada originates in the forests of Amarkantak in the Maikala Range. Downstream, worshippers set prayer lamps afloat on this, the holiest of Indian rivers.

Photo:Rainer Horig

I had studied Sunderlal’s river. For about 100 km. upstream the river traversed one of the largest remaining forests of central India. Here, in the vicinity of the Punasa Gorge, wildlifers have observed tigers, leopards, bears, wolves, pangolins, flying squirrels, hyaenas, blackbuck, chital and sambar. Monitor lizards still bask on rocks in this secluded stretch and mugger crocodiles fish its productive waters. The canopy supports a rich avian diversity that includes eagles, hornbills, owlets, jungle fowl and more. Even my untrained eye can see that the river serves as a refuge to rare and diverse species. But, as a broad line of whitewashed stones stretching across the riverbed into the forest a few kilometres upstream of Omkareshwar indicates, they live under Damocles’ sword.

Wandering in these forests rejuvenates my senses. Sunlight breaks through the canopy of teak, mahua and other mighty trees. The dusty road reveals pugmarks of deer and wild boar, occasionally traces of a big cat. Calls of monkeys, cuckoos and mynahs fill the air. The smell of the earth is intoxicating and refreshing. Perhaps a big cat watches me from the undergrowth? This is the fabled land that made the Indian term ‘jungle’ familiar all over the world. Captain J. Forsyth narrated his explorations in the Narmada valley more than a hundred years ago. Rudyard Kipling came to the Mahadeo Hills to write his famous Jungle Book. To me it appears as one of the great treasures that this great country still possesses. These vast forests give birth to a network of big and small streams that nurture the mighty Narmada. But just 2.5 per cent of the Narmada’s catchment is protected; by the National Parks of Kanha (924 sq. km.), Pachmarhi (461 sq. km.), Satpura (524 sq. km.) and the Bori Sanctuary (485 sq.km.).

The holy parikrama

“Narmadey Har!” Five lean figures repeatedly bow their heads to the ground in front of a black stone statue, wrapped in red silk and put up under a white-tiled canopy resembling a Hindu temple. “Now offer the flowers you have brought, one by one,” commands a half-clad priest sitting nearby. He starts singing a hymn appeasing the goddess, the five pilgrims repeating the refrain. “We hail from Sopari in Narsinghpur District,” says Balwan Singh who owns a small farm there. More than a year ago they had started out to circumambulate the Narmada river, in the footsteps of scores of pious Hindus who have performed the holy ‘parikrama’ since time immemorial. “I left home after four of my children died in quick succession,” explains Balwan Singh. “I wanted to overcome the shock by worshipping the goddess Narmada so that my two remaining children would survive.”

Imagine walking barefoot for 2,600 km. with just a blanket and a begging bowl in your hand. You would surrender your frail existence to the river and its people. Everyday you shall offer prayers to the river by floating tiny oil lamps on the water. Never turn back, always keep the river to your right; that is the custom! You would probably relive the whole journey of your life again. You may discover a whole new world or find answers to long-pending questions. “I have experienced so much joy, so much tranquillity,” narrates Balwan Singh. “Goddess Narmada takes care of all my needs, sometimes she even speaks to me. Everywhere we go, people offer us water, food and a place to rest.”

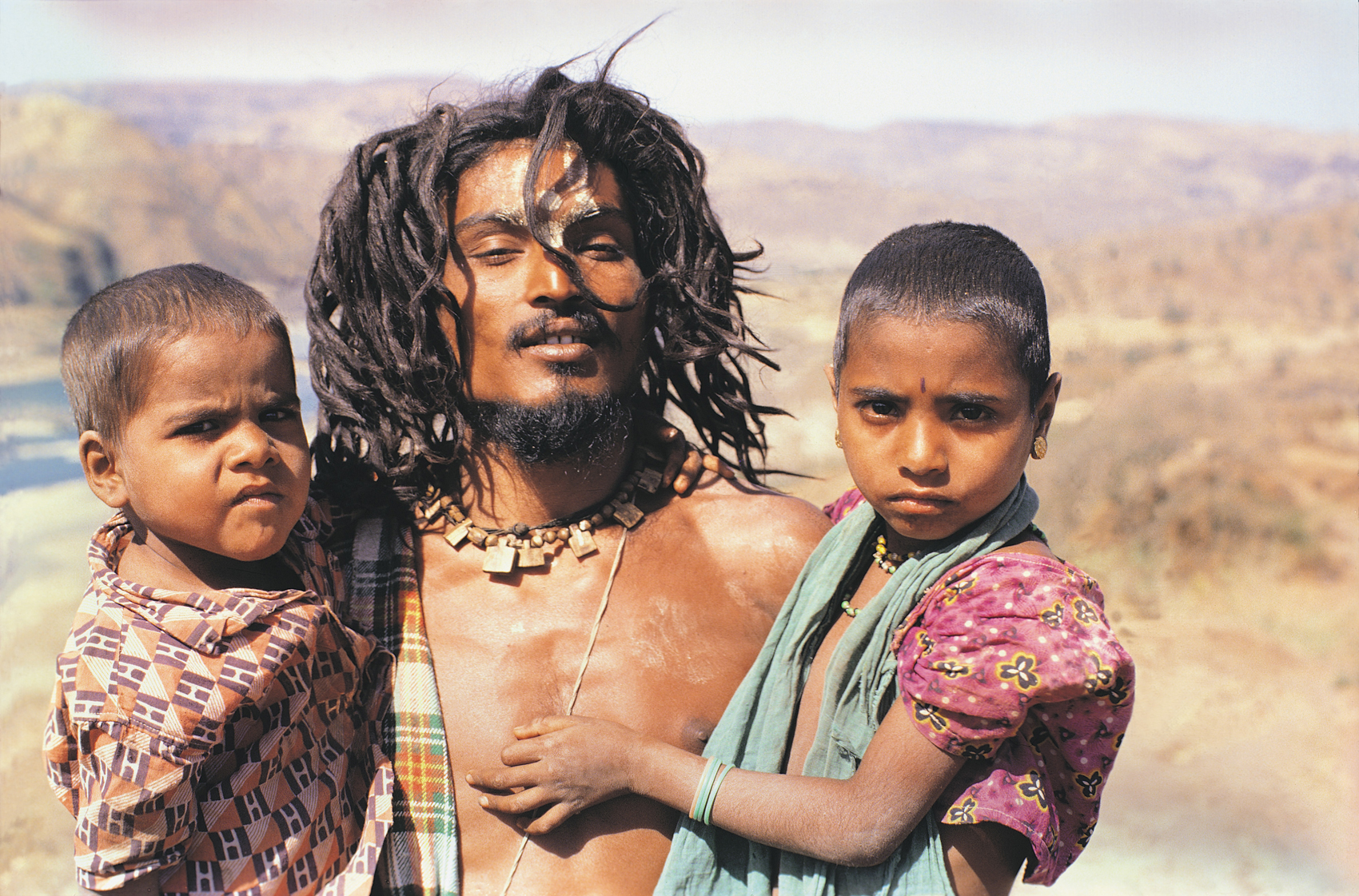

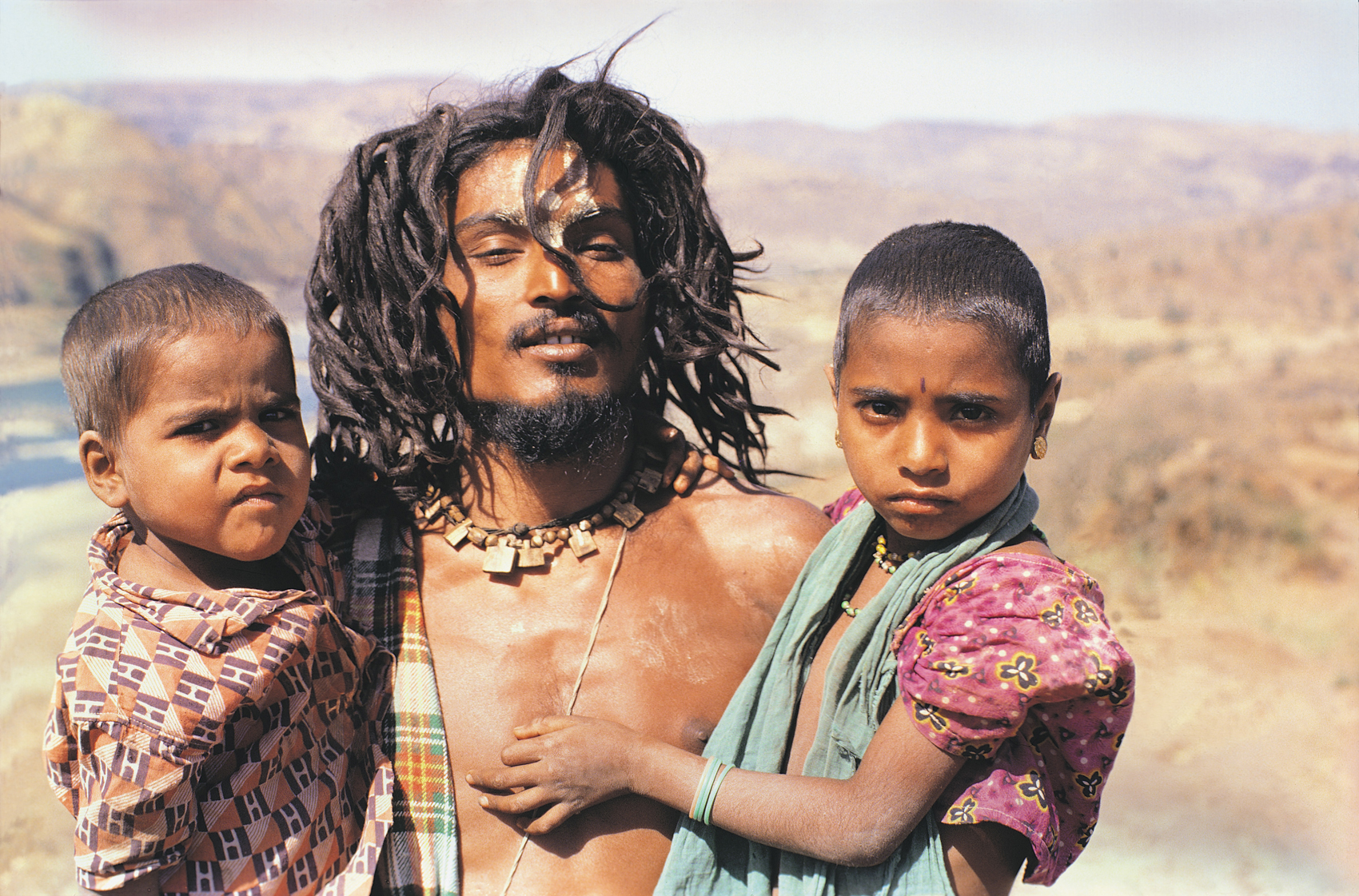

The biodiversity of the Narmada Valley has barely been documented. Thousands of proud tribals including Jayaprakash Naga of Bhushya village on the Madhya Pradesh – Maharashtra border still continue to hold on to an ancient way of life. But a series of dams may forever alter the ecology and cultures based around the river.

Photo:Anish Andheria

Balwan drags out a small wooden picture frame from his bundle. A lady in a red silk sari, riding on a crocodile through turbulent waters, is spreading her arms to deliver blessings and wealth. Green hills in the background are dotted with shiny white temples. An apt description of the Narmada river and its soul. The old seers wisely imagined her riding a crocodile. These fierce reptiles act as a kind of river police, eating carcasses and large predatory fish. Crocodiles are for rivers what tigers are for woods - indicators of a healthy ecosystem. But in the not too distant future, the

goddess Narmada may be deprived of her trusted helpers.

I have always been fascinated by the idea of worshipping rivers. Rivers are key witnesses and facilitators of man’s evolution. From the Stone Age onwards people have set up their dwellings near flowing waters. The first cities and industries were built on the banks of famous rivers. Unfortunately, modern city-dwellers like us have forgotten the importance of water, whose source we imagine is not some distant, forested valley, but the nearest tap.

The biodiversity of the Narmada Valley has barely been documented. Thousands of proud tribals including Jayaprakash Naga of Bhushya village on the Madhya Pradesh – Maharashtra border still continue to hold on to an ancient way of life. But a series of dams may forever alter the ecology and cultures based around the river.

Photo:Sanjiv Bamroo

Giver of joy

All along her 1,312 km. long course, the Narmada is decorated with thousands of Hindu-temples. To villagers and townfolk she is like a mother: ‘Narmada Mai’. They arrange festivals in her honour like the spectacular ‘Narmada Jayanti’, when thousands of oil lamps are floated at night from the sprawling bathing steps of Hoshangabad. Narmada literally means ‘the giver of joy’. According to ancient Hindu scripts, the Puranas, the river was born out of a drop of Lord Shiva’s sweat while he was dancing on the hills. She has been portrayed as a strong-willed virgin who, with quicksilver movements, escapes all the advances of heavenly princes. That’s why she is also called ‘Rewa’, the leaping one.

Amarkantak, the origin of the Narmada, is 1,057 m. above sea level in the Maikala range of eastern central India. In an elongated valley on a plateau, the waters of numerous springs collect to form a tiny rivulet. It flows into an ancient pond surrounded by a dozen shiny white temples. Scores of pilgrims come here every year to perform bathing rituals in the river’s virgin waters. In the main temple they offer prayers to a colourfully decorated black basalt-stone statue of Narmada Mai.

The Narmada river has been portrayed as a strong-willed virgin who, with quicksilver movements, escapes all the advances of heavenly princes. That’s why she is also called ‘Rewa’, the leaping one. This waterfall at Beraghat near Jabalpur is one of the largest on the Narmada.

Photo:Rainer Horig

From here the young river meanders westward through colourful meadows endowed with lofty sal forest. After a few kilometres it plunges over a 24 m. high cliff at the Kapildhara falls, down into a narrow gorge that is overgrown with thick jungle and strewn with cyclopic boulders. I rest there on a rock and observe the games dragonflies play across the clear water. Their violet and purple bodies glisten in strokes of sunlight that break through the forest’s canopy. I listen to the river, its roar and its murmur, its gurgles and splashes. I try to count jumping drops and imagine the long journey ahead of them. It may take a few months until they finally join the ocean. This exciting drama began millions of years ago and will continue for millions of years. I sense the breath of eternity here.

The Narmada is the only major stream in India that flows in an east-west direction, in a rift valley formed 400 million years ago by movements in the earth’s crust. Tectonic activity continues, as earthquakes at Jabalpur (1997) and Khandwa (1998) painfully demonstrated. The so-called Narmada-Tapti-Son lineament, an east-west depression in the Deccan peninsula, channels the monsoon winds from the Bay of Bengal to the heart of India. Heavy showers cause huge flash floods for which the Narmada is notorious.

Crocodiles in peril

Scientific evidence suggests that crocodiles have lived in the Narmada’s waters for at least two million years. But neither the forest department nor the reputed Bombay Natural History Society can confirm just how many crocodiles survive in the river today. Romulus Whitaker of the Madras Crocodile Bank estimates the number of muggers Crocodylus palustris, to range from one to two hundred. A small population of saltwater crocodiles Crocodylus porosus, survive in the Narmada estuary near Bharuch.

Crocodiles feed on carcasses and predatory fish thereby cleaning the river and helping fishermen enhance their catches. There are just about 10,000 muggers left in the wild in India. Their survival is threatened by rampant pollution of rivers, by poachers as well as by the construction of large dams. “Dams hamper the movement of crocodiles along the course of the river,” says Romulus Whitaker. “Since most of the shallow pools get flooded they find it difficult to prey for fish in reservoirs. When its water is released during the summer season, crocodiles’ nests become isolated and the females can neither protect them nor help the babies to hatch. Wherever we have done surveys of crocodiles in dam reservoirs we saw only big crocodiles, no small ones, which means their recruitment rate is next to nothing!”

The cradle of life

Within her 99,000 sq. km. basin between the Vindhya mountains to the north and the Maikala, Mahadeo and Satpura ranges to the south, the Narmada has formed an exciting variety of landscapes. In a continuous process of erosion, grinding of rocks and sedimentation, the river transports huge amounts of boulders, sand and clay from the hills to the sea. Cutting through hard rock it has formed gorges like the famous marble rocks near Jabalpur and the Punasa gorge with waterfalls at Punghat and Dardi. The broad alluvial plains created by millions of years of sedimentation are said to be amongst the most fertile soils in India. The vast sheet of water in its funnel-shaped estuary near Bharuch provides breeding grounds for riverine as well as marine fish – a cradle of life! “Narmada’s sediments are a documentation of the evolution of life in India,” explains palaeontologist, Dr. G.L. Badam at the Deccan College in Pune. “By analysing fossil remains of gaur, buffalo and some deer we were able to establish proof of their evolutionary origin on Indian soil!” According to Dr. Badam the valley at one time was home to hippos and 22 different species of elephants! His colleague Arun Sonakia unearthed a 150,000 to 200,000-year-old human skull from the river sediments at Hathnora near Hoshangabad. This could be the earliest evidence of man in India. Ancient cultures have survived till today in the Narmada valley.

At Dediaghat, 13 km. below Punasa, the river sculpts an impressive rock formation. It is also characterised by deep gorges at sites like Jabalpur’s famous Marble Rocks.

Photo:Sanjiv Bamroo

Festival of colours

Cymbals and drums echo through the crystal-clear night calling young and old to a hillock near Domkhedi village. Up there hundreds of dancers whip up the dust. The girls’ saris glow in the soft moonlight. Young men arrive like large cats on the prowl, clad only in loincloths, their dark skin decorated with a pattern of white circles. As the day dawns a huge pile of firewood is lighted. The leopard dancers put on large hats made from peacock feathers and tie brass bells to their wrists and ankles. Beating drums they draw circles around the fire and slowly fall into a trance.

With the spring festival of Holi the new year dawns in Domkhedi. Yesteryear’s sorrows go up in smoke with the bonfire. Here, where the Satpura and Vindhya mountains close up to squeeze the river Narmada into its last gorge, life has hardly changed over thousands of years.

The end of history

Domkhedi’s inhabitants belong to the eight-million-strong Bhil people, one of western India’s indigenous tribes who still maintain a close relationship with the land on which they survive. They cultivate maize, millet (jowar), lentils (tur) and vegetables on their hilly, rainfed fields. Women collect leaves, fruit and roots from the forest to supplement their diet and ensure against crop-failure. In times of distress they offer prayers and coconuts to mother Narmada. “We are adivasis. We are born for a life in the jungle,” explains Pervi Bhilala who, with her three brothers, owns 15 acres of land in Jalsindhi village on the opposite bank of the river. “This land means everything to us, it nourishes us and our animals. We just work for four months in the fields to gain enough food for the whole year.”

Domkhedi and Jalsindhi gained nation-wide prominence during the 1999 monsoon. Because of the upcoming Sardar Sarovar dam in Gujarat, the impact of the Narmada’s floods was magnified and water rose up the hills into both the villages. But the proud Bhils refused to vacate their homes even though they risked death by drowning. Fortunately Narmada Mai stopped rising just as the waters reached neck-height.

The author at the historic Maheshwar Ghats on the bank of the Narmada River.

Photo:Rainer Horig

Standing on the 85 m. high crest of the Sardar Sarovar dam I am shaken by contradictory emotions. The huge mass of concrete poured right into the river’s way, the gigantic canal heading off from here to a distance of 500 km., the mighty machines and transmission lines certainly represent a technological achievement. But at what price? The mighty river is raped, its holy waters pressed through pipes and turbines and all living creatures in it crushed. Will Narmada Mai tolerate such blasphemy? Is India really prepared to sacrifice its natural wealth, its history, its people and its soul? One thing I know for sure: the struggle over this river will continue for many years to come. And people of faith will always be there to tell the true story.

Medha Patkar with Narmada Bachao Andolan supporters.

The Price to Pay! Impacts of the Narmada Dams

Medha Patkar with Narmada Bachao Andolan supporters.

The Price to Pay! Impacts of the Narmada Dams

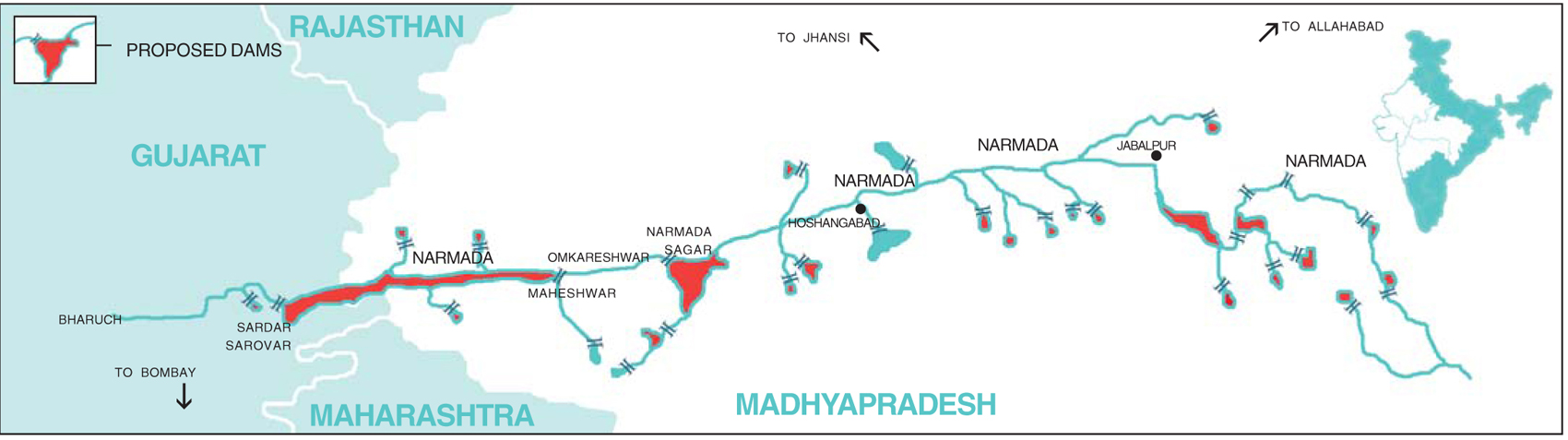

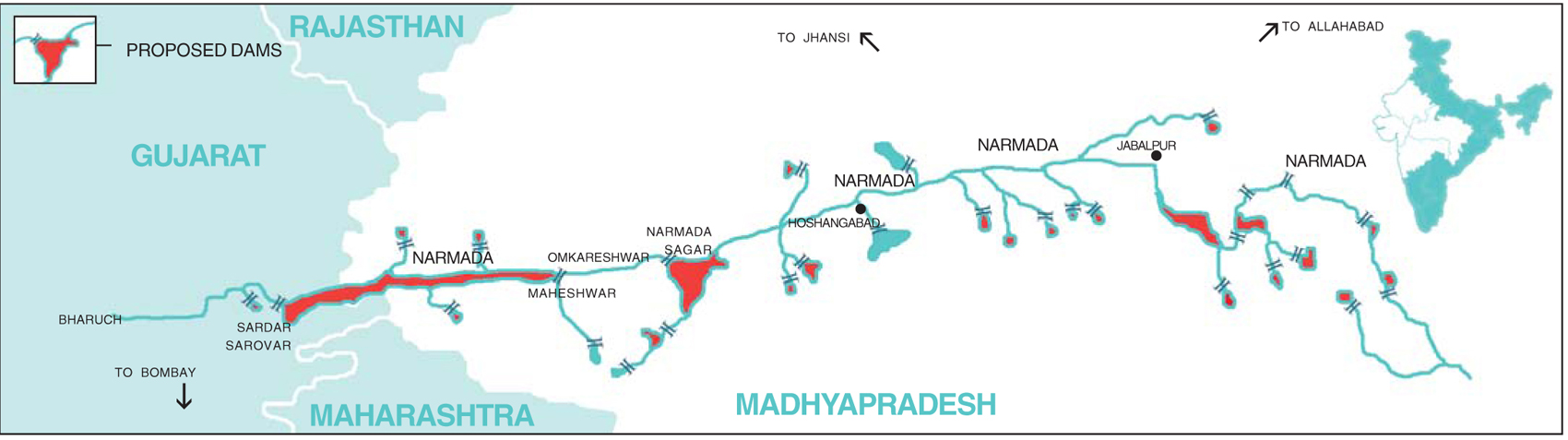

In the 1960s, when trust in technology was still intact, plans were put up to construct 30 huge dams and thousands of small weirs across the Narmada river and its tributaries. The Bargi and Tawa dams have been completed, half a dozen more are currently under construction. Half of the river is going to be turned into still waters. The ecology of the region will be thrown off balance:

l More than 50,000 hectares of forest and an equal amount of farmland is to be drowned.

l The natural transport of stones, sand and nutrients will be impeded, affecting agriculture and fisheries.

l Migratory fish, crocodiles and turtles and an ancient aquatic system will vanish.

l Wild animals will either drown or be driven out of their forest home.

l Many archaeological sites will be lost forever, especially around Maheshwar and west of Hoshangabad.

l Around half a million farmers, boatmen and

adivasis will be uprooted and abandoned to an uncertain future. Inept rehabilitation schemes will never be able to compensate them.

l Thousands of fishermen downstream of the dams, even in the coastal waters of the Gulf of Khambat will suffer because of the inevitable decline in fish populations.

l The age-old tradition of the

Parikrama will come to an end, since the path on the riverbanks along with temples and

dharamsalas (lodges) will forever be buried under water. The village folk who by custom serve the pilgrims will be dispersed far and wide, away from the waters. With them will vanish the oral history of the Narmada.

l The huge reservoirs will provide a fertile environment for vectors of infectious diseases like malaria, bilharciosis and diarrhoea.

l Its massive weight may induce earthquakes in the tectonically active region.

Alternatives to big dams exist. Anna Hazare and Rajendra Singh (

Sanctuary Vol. XIX No. 5) have transformed arid, thirsting villages in Maharashtra and Rajasthan with small watershed-based irrigation schemes and afforestation under active participation of the people.