On the Wolf Trail

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 38

No. 4,

April 2018

By Lalitha Krishnan

A casual conversation in a remote high-altitude village three years ago navigated my life path astray. I had visited Spiti in Himachal Pradesh with my family only to discover that there’s more to the land than meets the eye. I saw Spitians dealing with life in their inherent resilient way. If growing food in a windy desert 4,000 m. above sea level, hauling snow melt by hand, walking 10-15 km. to fetch dung-fuel in a treeless landscape, getting little or no access to healthcare, gaining daily wage employment and educating their children wasn’t enough, they had predator attacks on their precious livestock to deal with.

A Victim of Myth

Life in Spiti isn’t as peachy as a biker’s Facebook post and in spite of the Spitian’s deep-rooted connection to the earth and acceptance that predators too need to eat, when livestock is killed, it’s the absolute last straw for the owner. Sometimes someone, and in this scenario, the wolf – the underdog – often pays the price. Wolf attacks on livestock do occur but in far fewer numbers than peoples presume. It’s more likely to be a combination of demonising wolf myths, the physical presence of wolves and the need for a scapegoat that brings forth people’s wrath on wolves. As I recently discovered, it’s the same story even a continent away, in the affluent world of Lower Saxony, Germany: “the wolf has to go.”

Though I never personally saw or heard of a proven wolf attack in Spiti while I was there, the undercurrent flipped a switch in my over imaginative brain. I decided there and then I needed to do something about an animal I really knew nothing about and had never set eyes on – the intelligent and elusive Himalayan wolf Canis himalayensis.

Unchartered territory!

My limited knowledge of wolves comes from reading novels and not research papers. Somewhere in my subconscious, I carry this image of Farley Mowat transporting jerry cans of vodka in the guise of aviation fuel as he prepares to fly out in search of wolves, alone, in sub-arctic Canada. He lived like the wolves, urine marking his territory and eating mice when there was no caribou. I picture Jiang Rong (pseudonym), the young Chinese student, during his harsh posting in inner Mongolia, stumbling on the pack of wolves that inspired his most fascinating novel in the thick of the Chinese revolution. I cannot but mention Mark Rowland, the philosophy professor, who kept a wolf called Brenin − posing as a pet dog − in the U.S. for the whole duration of its lifetime. Rowland got away with it. Running and living with Brenin, nursing him through sickness, Rowland finally, gave him the noble burial he deserved and went on to write about lessons learnt from the wild. All of it sounds like romantic fiction, but isn’t.

I am neither qualified nor trained to be a conservationist. I made a deal with myself. In October 2016, I decided to go look for wolves to convince myself they exist instead of chasing ghosts. Volunteering with an NGO in Spiti, I went on to acquaint myself with the local community: to get their perceptions of wildlife, talk about conflicts with wolves and snow leopards, get their views on tourism and listen to ideas they might like to share. After speaking to several families privately in their homes and fields, I was surprised to find out that the biggest threat to livestock in winter was neither the wolf nor the snow leopard, but the feral dogs that hunted in packs and killed livestock as a result of food scarcity. Naturally, the locals look unfavourably on dogs as well, but that is something I hope will change in the future.

Wild Sighting

As my stay drew to a close, I scanned the horizon for my ‘wolf sign’. My chances of spotting a wolf were looking bleaker than finding a needle in a haystack. Several people predicted so. I had a single free day – a single window – to try and stay true to the wolf and myself. I turned a deaf ear to bad counsel and marched on regardless, in search of my elusive underdog. It was more challenging than I assumed.

The author’s deep fascination and love for wolves took her to the mountains of Spiti in India to Lower Saxony in Germany, where she volunteered through NGOs and citizen science projects. Photo courtesy: Lalitha Krishnan

On a cold evening, I travelled to an unfamiliar village, the base for my ascent to a high-altitude lake at approximately 4,500 m. Starting out at 3:30 a.m., I trekked under a star-dusted sky accompanied by Kunga, a local. The territory was new to both of us. In no time at all, we were both cold and lost (unknown to us, there was a perfectly easy path up). I was clambering up − sometimes on all fours − a 60º scree slopes, which felt more like 75º. I moved on mindlessly, like a determined, migrating beast. By the time I ascended to the top, I was so breathless I wondered if it was high-altitude or plain exhaustion that would kill me first.

Then, in one instant, all thoughts and doubts were erased. I stood frozen to the spot. There, before me, in the first light of dawn, I saw running one after another across a dry lakebed, a pack of what looked like wolves. Not one or two but three or four. Could they have been dogs? They certainly looked like wolves. Almost immediately, I heard a short warning bark to my right and then, a howl.

I felt the surface of my skin suddenly chill in response to my first wolf howl in the wild. I turned to see a solitary wolf, classically silhouetted on a rock, head thrust back towards the sky, communicating our presence to the rest of the pack. In a matter of seconds, they were all gone. Just like that. My mirage disappeared as rapidly as it had emerged leaving only footprints. Luckily my companion saw the wolves too. We looked at each other, idiotic grins morphing our wind-crisped faces. I got my sign.

Back on the Wolf Trail

I basked in that after glow of my wolf sighting for a few months; I woke up to the fact that I needed to pick up conservation skills. I completed a short but excellent course at the Wildlife Institute of India (Dehradun) following which I signed up for a first of its kind, citizen-science wolf-monitoring project in Germany in Lower Saxony in 2017. Biosphere Expeditions, the award winning, not-for-profit NGO that runs the programme is a veteran of citizen-science projects all over the world. I think they were a little surprised to find a wolf crazy Indian on board. Frankly, I surprised myself but I knew I was in the right place when I met up with a bunch of wolf-loving volunteers as eager as I am to contribute to wolf conservation.

Wolves are endangered and protected in Germany, yet wolf conservationists face similar challenges to their counterparts across the world. Especially, though not surprisingly, they’re frowned upon by hunting associations. After an extensively long period of near extinction, in the year 2000, the wolves returned to Germany, through Poland. Germany is working hard to safeguard the exchange of wolf populations of northern and southern Europe.

Wolves are habitual wanderers, travelling anywhere from 30-70 km. a day. The young break away from the pack after reaching maturity at around two years to establish their own territory.

A research scientist affiliated with Nature and Biodiversity Conservation Union (NABU) and a staff member from the Biosphere Expedition led our wolf mission. Between the two, they had our daily tasks all graphed out.

Once again I was told, I would never see a wolf in the wild. We started with a promising visit to the Wolf Centre where we were introduced to wolves and where a wolf expert spoke to us at length. It was thrilling to see and observe a complete wolf pack, see different breeds and learn about their social dynamics.

A wolf can pick up sounds up to 16 km. away. Wolf packs I was told usually include the parents (who bond for life), young wolves (yearlings) and four to six pups. Parents are accepted as absolute authority and yearlings babysit. The numbers in a pack stay the same more or less when yearlings split from the group. They choose to settle close by or travel even up to 100 km. away and attract mates by howling.

A typical wolf pack in central Europe can travel 150-350 km. depending on the availability of prey and the presence of neighbouring packs or single wolves. I have heard of fish-eating wolves but was surprised to learn certain breeds also eat fruit. I learnt a great deal about the wolf in a very short time at the Wolf Centre. Information centres like this one should be easy to replicate in order to educate people about wolves and dissipate myths that seem to follow the animal universally.

“Wolves avoid people but not the human-made structures in the landscape,” says Markus Bathen, NABU wolf expert. I know this to be true. Walking in teams of two to three, looking for evidence of wolves, I was surprised when we discovered most of our finds (tracks and scat) on wide, publically used forest roads. Even in Spiti, locals often sight wolves on vantage points on the hills edging the village, keeping their distance. Wolves I learnt don’t need large tracts of wilderness as they adapt well to cultural landscapes. They don’t normally pose any threat to humans.

Scat signs such as these that the author came across during her expeditions in Germany help researchers determine wolf populations and understand their behaviour. Photo Courtesy: Lalitha Krishnan

The wolf expedition was hands on. I came away learning about standard criteria for evidence collecting, types of monitoring, using a GPS, recognising and measuring tracks, documenting and filing data sheets correctly and knowing how to identify wolf scat. The lay of the land–flat, unlike Spiti – made walking 10-17 km. a day to undertake all of this easier.

The paw tracks of a wolf are quite similar to that of a dog, determining the size, and differentiating the trots was challenging. We didn’t come across a single carcass or wolf-kill. I felt privileged to be able to walk with Theo Gruentjens, one of Germany’s many government appointed Wolf Ambassadors who besides being a wonderful person is an absolute authority on wolves. The whole concept of wildlife ambassadors educating, guiding and leading the uninitiated is truly an interesting one.

The Hunter and the Hunted

Despite knowing that wolves in Germany are legally hunted, I was shaken by the number of hunter lookouts on field and forest clearings. Parts of the forests too are leased out to hunters. It wasn’t the hunting season when I visited or I would have been looking over my shoulder ever so often. To be honest, the whole concept of hunting feels alien. I am grateful India does exercise some caution in handing out hunting licenses. Poachers and smugglers are trouble enough.

Another cause of wolf deaths in Germany is roadkills (see "Roads to Nowhere" of this April issue). Wolves, I heard, don’t connect cars with humans. Knowing that wolves love roads and move at night, I’m not too surprised.

In Spiti, wolves and leopards have a reputation of attacking more than one sheep in a pen, “sucking their blood” before moving on to another, leaving a number of victims behind – including, in a sense, devastated sheep owners. I wondered about that till I heard a logical explanation in Germany.

Sheep do not flee like deer and wolves need to chase to kill. If a wolf decided to attack a sheep herd, it has to decide which one to follow. The hunter instinct kicks in only when sheep scatter. When sheep regroup and huddle together the wolf stops attacking or hunting. When the sheep start moving again, it needs to select a new sheep to hunt down.

Keeping Wolves at Bay

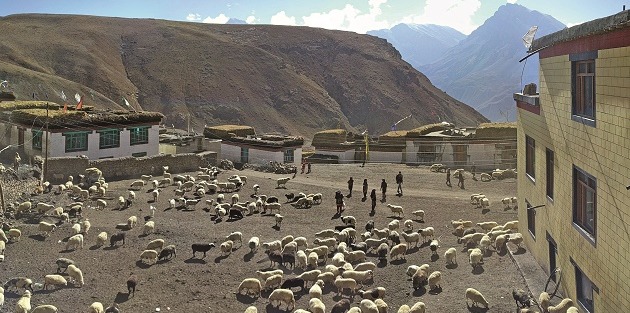

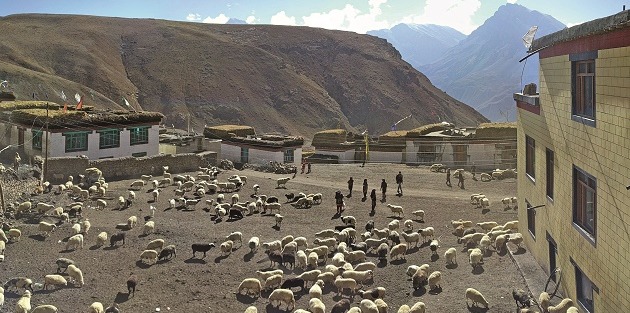

Livestock herders both in India and Germany employ indigenous techniques such as collective herding in Spiti. Photo courtesy: Lalitha Krishnan

In Spiti, I watched villagers collectively shepherding their flocks to avoid predator-confrontation. It works. They have a professional shepherd on the payroll. It was fascinating to see the morning routine of yaks, sheep, donkeys and dzos being herded out of the village together bleating and braying in excitement.

In Lower Saxony, farmers invest in (dig proof) electric fences fixed into the ground, as wolves are known to dig right under a fence to get at prey. Another popular livestock protection these farmers employ is working dogs. We visited a farm and met up with German farmer Holger, who keeps Turkish Kangals – a dog breed, which takes its job seriously. They blended in with the sheep and look similar to mountain Gaddi dogs found in India. In spite of being a dog lover, I didn’t attempt friendly overtures. Only when I saw a pup did I reach over the fence to immediately reel back, substantially shocked. I think I made Holger’s day reaffirming that both his dogs and fences were in top working condition.

Livestock herders both in India and Germany employ indigenous techniques such as using Turkish Kangal dogs in Germany to keep wolves and other predators at bay. Photo courtesy: Lalitha Krishnan

Our group (one of four) covered 322.45 km. (on foot and bike) in four and a 1/2 days, collected 12 wolf scat samples, out of which six were preserved in ethanol for DNA analysis. We were also very lucky to come across a wolf’s track of more than 100 m. of direct register trot (complying with the official wolf monitoring criteria). Our findings, datasheets and documentation have been sent to the Wolfsbureo for approval. Peter (Expedition Scientist) and Malika (Expedition Leader) have promised to keep us updated.

Collective group findings of all four Biosphere wolf expeditions will help researchers determine the area of occurrence, distinguish between adjacent territories, establish pack and population size and understand reproductive behaviour/patterns. These facts are significant for generating a favourable conservation status for the wolf.

Three years ago, I wondered how the wolf would fit into my life. I am beginning to believe my journey is gaining momentum and focus, much like the direct register trot of the animal I’ve learnt to respect. I may never be a full-fledged conservationist, a Farley Mowat, Jiang Rong or Mark Rowland, but I’ll settle for incognito Wolf Ambassador any day. Wolf willing.

Author: Lalitha Krishnan