Salim Ali: An Appreciation by Bittu Sahgal

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 29

No. 4,

April 2009

By Bittu Sahgal

I loved the old man deeply. As did so many others who were touched by Sálim Ali's warmth, intellect and good humour over the years. Yet I do not mourn his passing, I cannot. He still lives inside me, continuing to inspire curiosity, tolerance and far-sightedness in much the same way he did when I visited him at Pali Hill six weeks ago - the last time I saw him alive.

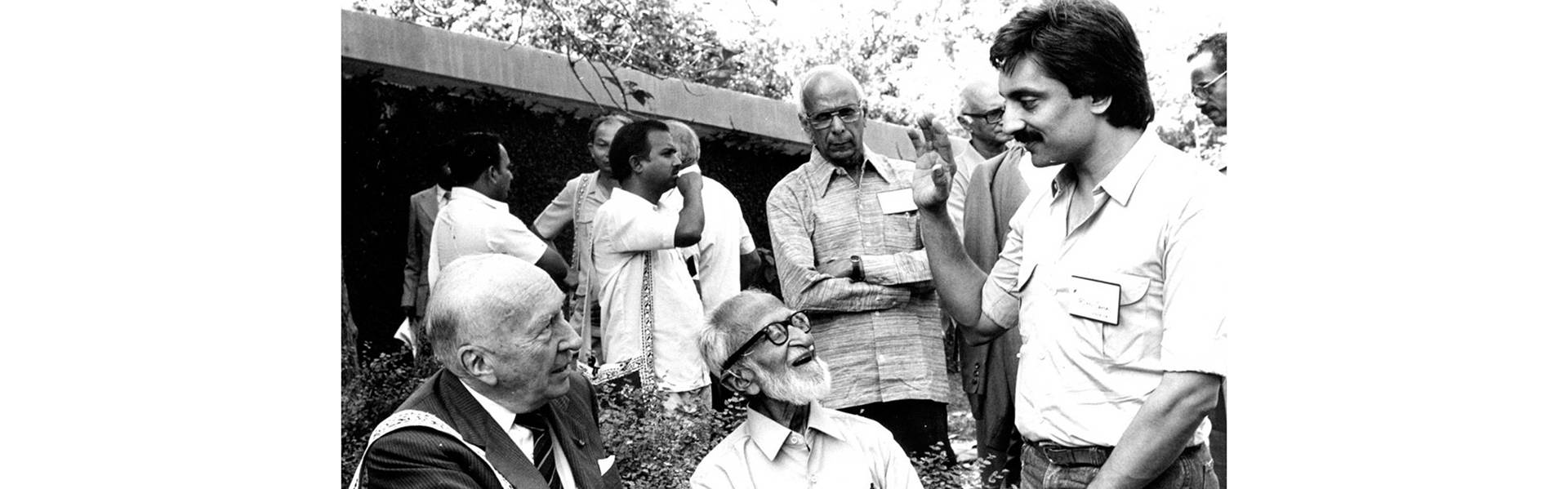

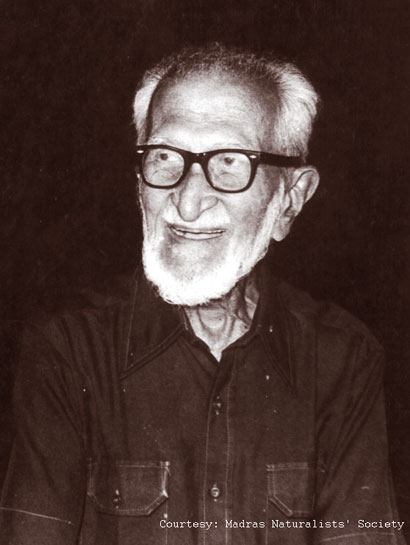

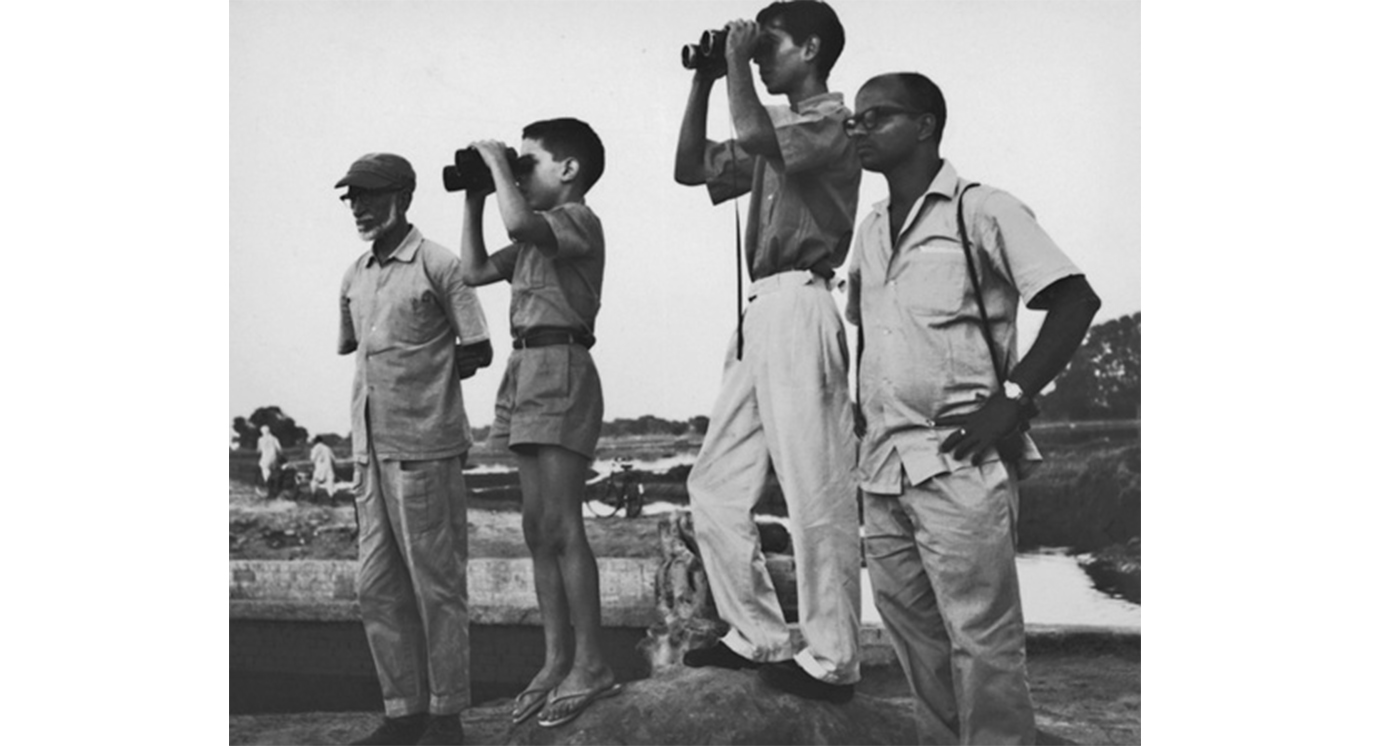

Photo courtesy: Madras Nauralists' Society

Photo courtesy: Madras Nauralists' SocietyHe always looked frail, but by now the crossfire between old age and illness had sapped even his legendary stamina. "Just feel these decrepit bones," he said, irritated and let down by a body, which his sharp, alert mind had hopelessly outlived; 91 years would be an eternity for most, but Sálim Ali was still so vital. He still had so much more to do. It was his incredible appetite for life, in fact, which infused him with the youthfulness for which he was so famous.

He'll forgive the description, but Sálim Ali was a celebrity. When he passed away telegrams and messages came pouring in from the President, the Prime Minister, the Chief Minister, the Governor and a host of other highly placed individuals, some of whom may still not fully comprehend what he stood for all his life. I can't help thinking that, if he could, the old man, a twinkle in his eye, would have remarked, "These good wishes are very welcome, but how about a nice fat cheque to the Society instead - that would be so much more useful!"

Contrary to what most people assume, Sálim Ali was not an animal or bird lover. Yes, he was totally fascinated by things natural - plants, insects and even the birds he came to be associated with. But in truth, his life was spent exploring the wonder and utter usefulness of nature without once becoming emotionally attached to the 'sanctity of life' concept that so many people still confuse with conservation. He hunted all his life, though he was scathing about some latter-day shikaris who respected neither rules, nor the animals they hunted. His expression took on a bemused look at the subject of religion. One suspects he thought of religious fanatics as children playing God! He realised the power of money and harnessed it whenever he could for his first love, the BNHS. But he never seemed to care much for money personally, except where it helped him repair his hideaway home at Kihim, or travel to some distant forest. Curiously enough, he seemed fascinated by the new Maruti cars and mentioned more than once that he wished he had a Maruti to drive him around! That was the limit of the materialism I was able to detect in him.

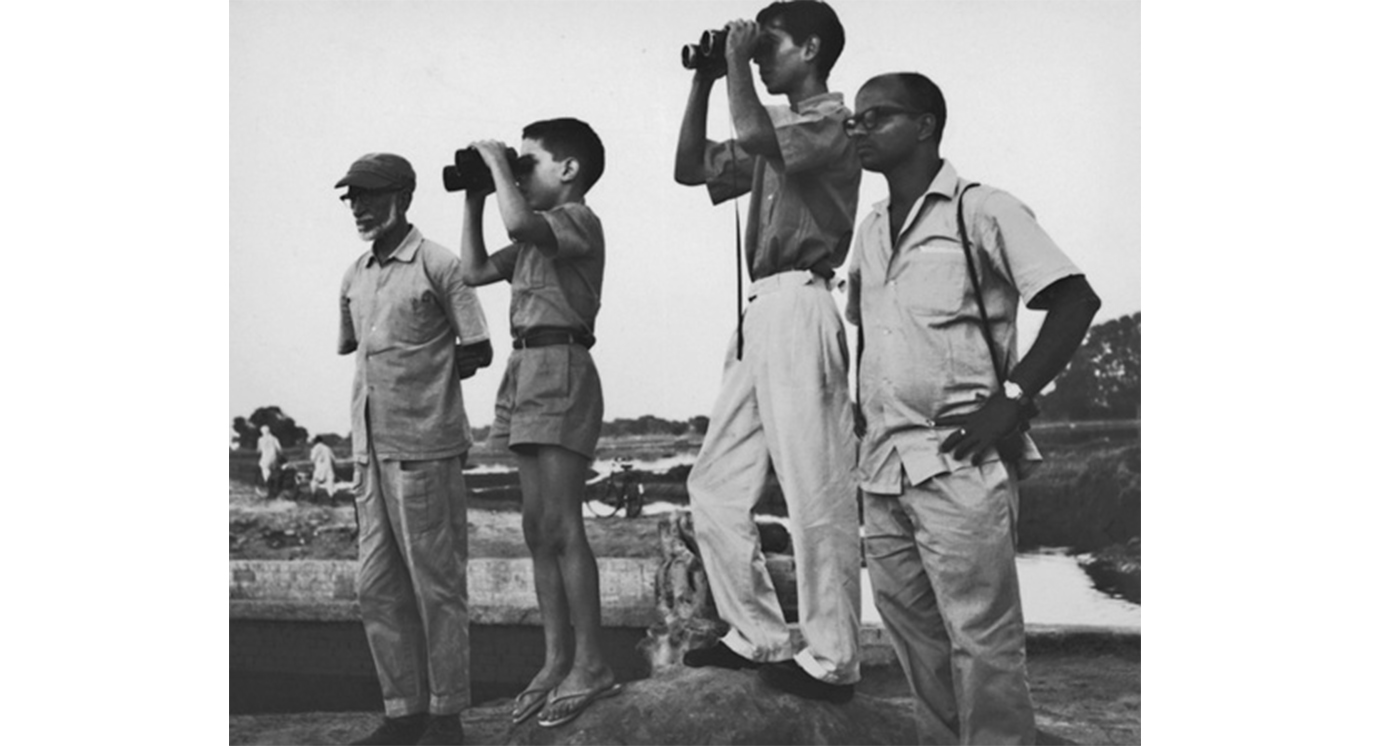

"Why don't these people understand?" he often used to ask when he heard of the destruction of yet another forest or grassland. And then, with a resigned look on his face, "I suppose I've done my bit, it's now up to you younger people." The frustrations of being eyewitness to the most destructive period in the natural history of India must have been hard, but that never stopped him from persisting in his efforts to document the diversity of the natural world. Nor did it stop him from fighting to change people's attitudes towards nature conservation. An inveterate optimist, he took strength from the fact that young people had of late become actively involved in conservation. I don't think he ever really considered the extent of his own role in infusing them with such purpose.

But the old man has gone now. And instead of indulging in the sweet sorrow of mourning, those of us who loved and respected him are determined to work towards fulfilling some of his dreams, which we too came to share. To set up a National Institute of Ornithology. To consolidate the gains made by the Bombay Natural History Society (BNHS). To widen and strengthen the infrastructure in India for natural history field research. To introduce rationality into the minds of well-intentioned nature lovers. To convince India that good conservation would result in better lives for Indians. Sálim Ali's life was so entwined with the BNHS that at times it became difficult to separate the two identities. "While I am still alive," he would say, "use me to consolidate the Society's position." It was his major worry that after he died the government might reduce support to the BNHS' projects and that as a result the talented group of field scientists he had nurtured over the years would be disbanded. His charisma was also the mortar which bound scientists of very different temperaments, and made them work together.

Sálim Ali would want no poetic eulogies. What he would like instead is the assurance that his life's efforts were recognised, by those in power continuing to support the BNHS, where his indomitable spirit still resides. And that the scientists and naturalists he helped nurture agree to work together after his death to keep on documenting and understanding the natural world. And to continue their search for the mountain quail.

(First published in April 2009)