The Dhole: Up-close

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 39

No. 8,

August 2019

By Dr. Priya Davidar

I have always had mixed feelings about the dhole Cuon alpinus, or Asiatic wild dog. My first encounter was on a cold and rainy evening in the 1960s, when my father, E.R.C. Davidar, a lawyer, shikari and later a wildlife conservationist, first brought us to a property in the northern foothills of the Nilgiris, that he and my mother later purchased and named ‘Cheetal Walk’. A pack of wild dogs were dismembering a chital near an old disused well. It was a painfully fascinating but unforgettable sight.

The Shikari’s Competitor

Dholes are cooperative hunters and breeders. They hunt as a pack coordinating their movements by whistles and usually bring down prey larger than themselves, devoured quite rapidly, sometimes while still alive. The British hated them, terming them “vermin”. Fletcher (1911), a planter in the Nilgiri-Wayanad, describing them as “crafty, untiring, cruel and relentless as fate”, wrote, “the wild dog is the curse of the country.” Lt. Col. Phythian-Adams, then Honourary Secretary, Nilgiri Game Association (later renamed Nilgiri Wildlife and Environment Association), called them ‘the perfect swine’ and unleashed a war on them. A bounty was placed on their heads and many were massacred. This was probably because they were rivals to the ubiquitous shikaris of yore.

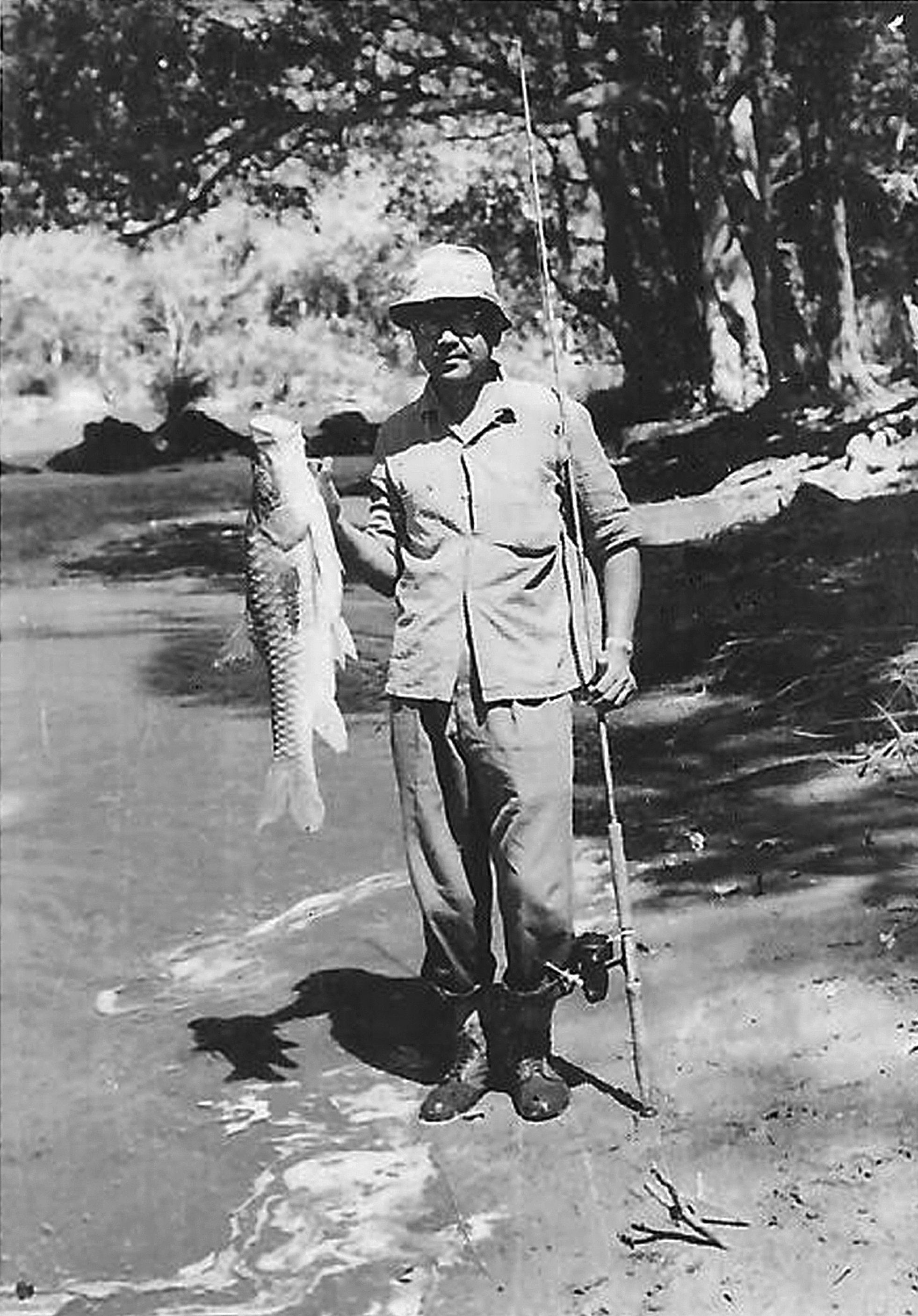

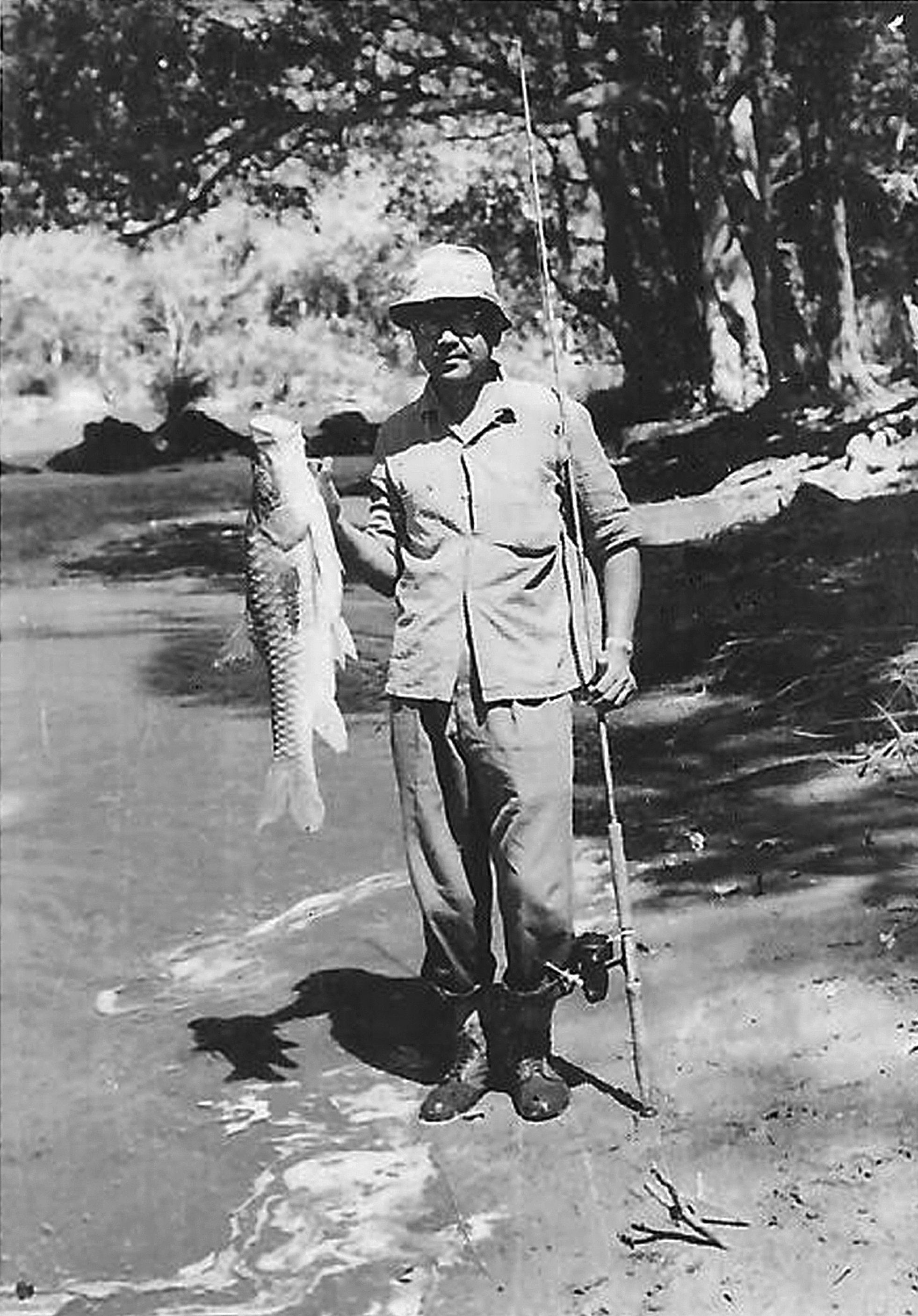

The author's father, E.R.C. Davidar, displaying a mahseer catch in the 1960s. Photo courtesy E. R. C. Davidar.

My father, who succeeded Lt. Col. Phythian-Adams at the Nilgiri Game Association, also began with a period of aversion towards the wild dogs. But after observing and admiring their rich social interactions, his opinion evolved, provoking welcome changes for the species in the Nilgiris. As he describes in his book Whispers from the Wild:

“I began efforts to provide much-needed succour to this embattled animal. To start with, I got the reward reduced, and further reduced its attraction by ‘cheating’ on payment by halving it for anything but outsize skins. When the dhole population started declining, the bounty was suspended, during the critical period. It is heartening to note that on the implementation of the Wildlife (Protection) Act of 1972, the practice of payment of bounty by the government for killing wild dogs and other ‘vermin’ was abolished.”

Wild dog numbers in the Nilgiris were known to fluctuate, possibly due to indiscriminate slaughter or disease. Distemper and rabies, transmitted from domestic dogs decimated their numbers, and it took the population years to recover. Fortunately, the Worldwide Veterinary Services (WVS) training centre based in Ooty, has vaccinated and neutered most of the village dogs, reducing disease risk for the dhole, and thereby stabilising their numbers.

After we constructed the house, we frequented Cheetal Walk more often, and the wild dogs were regular visitors, chasing down chital and young sambar into the river. Once the cries of a sambar fawn trapped in a pool brought a herd of sambar who kicked and chased off the predators. It was the first time we had seen such a victory of prey over predator.

We also had a pet wild dog pup called Bunty in the early 1970s that my father had found in the jungle. Bunty was deeply attached to my father, but did not tolerate any of us, least of all my mother, who had to put up with snaps and bites. We realised that they were not amenable to domestication, like the wolf. In spite of a long coexistence with humans, they could never be transformed into loyal doggies – you couldn’t take the jungle out of them.

Bunty (right), the wild dog pup we had adopted, begging Sandy, our cocker spaniel, for food. Photo: E.R.C. Davidar.

Our Resident Dhole Pack

In the early 2000s, a pack of 14 wild dogs frequented Cheetal Walk. These beautiful animals were more like flames as they flashed through the forest, chasing prey, followed by a heart-rending shriek of a deer. I would dread hearing this piteous cry, knowing that soon little would be left of the deer. Among this pack was a disabled male, weak and limping, probably a result of being kicked by a deer. I thought he was done for. However, Sukumar, a Kurumba tribal and a former mahout, who worked with my brother Mark, assured me that the pack would take care of the dog. Over the years the dog was still with the pack. He did not hunt but followed the group and obviously got some of the pickings. The 14 dogs became 18 over time with the disabled dog still going strong, showing how fiercely loyal and cooperative they are with pack members.

When we moved to Cheetal Walk in 2013 after my brother Mark passed away, the pack was still streaming through the property now and then

on a chase. They usually paid a surprise visit, and then disappeared. Their average home ranges are around 60-70 sq. km.

Once, I inadvertently got in the way of a hunt while seated on a rock observing wild flowers being visited by bees. A large chital stag headed rapidly in my direction pursued by the pack. My sudden presence disrupted the hunt, the stag got his chance to escape, and the disappointed dogs yapped and snarled at me from a distance. On another occasion while they were going around in all directions looking for prey, my brother Peter whistled like the dogs, and soon two squiggly half-grown pups dashed towards him enthusiastically, stopping abruptly and yelping in fear when they realised he was not a wild dog. Hearing their cry, one of the pack members came and took them away.

Dholes have complex and diverse vocalisations which help them communicate. A Russian team (Volodin et al.) showed that apart from the whistles and other calls, they use a ‘biphonic’ vocalisation that is a combination of a high frequency squeak and a low frequency yap, unique to each individual. They suggest that this could help recognise individuals in a pack.

A pack of dholes cooling off at a watering hole after a strenuous hunt in the Nilgiris. Photo: Jean-Philippe Puyravaud.

The Chase Goes On

A year later, the 18 had reduced to two, a male and a female, while the others were not to be seen. We assumed the pack had split up, or had met a sad end. Wild dogs are cooperative breeders, only the alpha male and female breed, and the satellites help with hunting and raising the pups. The two were assiduous hunters, not noticeably successful, often flopping into the water in exhaustion. We keep a ground level water tank for the deer and other animals and birds.

The male had a pronounced whitish throat and we named him Mari, a local tribal name. Within a year, another male and female had joined them, obviously from elsewhere, as they were adults. Success lies in numbers, as a larger pack can spread out to stalk and chase prey, and catch larger animals. Soon they were joined by their two female pups who were big enough to participate in the hunt. The six would show up unexpectedly, greeted by the swift rush of the deer getting away silently. There are usually no alarm calls from the deer, only by monkeys. The reason for this is not clear, but a swift and silent escape seems to be the only way out for the deer, considering the ability of the dholes to run quite fast over long distances. If a deer can escape silently, unnoticed, well and good. But as long as he or she remains in the sight or sound radar, the pursuit continues. A few, particularly the young, fell prey.

The dogs would take a break in the water tank, panting, and take off again, resuming the hunt. I saw them sometimes during my morning walks, and observed how the hunt often got disrupted by the thick carpet of Parthenium, an odious invasive plant. Since this plant is taller than the dogs, they have to jump through it to follow their prey. The deer are larger and move with greater facility through the Parthenium, and more often escape.

The dhole’s primary diet consists of hoofed mammals such as deer, wild pigs and this wild buffalo carcass scavenged by a pack in the Sigur river in the 1970s. Photo courtesy: E. R. C. Davidar.

The dhole often see us, but show neither fear nor friendliness, unlike the wild pigs and wild elephants, who most often become comfortable and even friendly, after seeing us repeatedly. I came to appreciate the tremendous courage and skills the dhole display to hunt. Their coordination, persistence and care are remarkable. They often wait for a missing member. They split up to trap an unsuspecting deer. There is always sharing, no quarrels, no fights. They love playing with each other, jumping and bounding away in the moments of peace they allow themselves now and then during their exhausting run.

My feelings towards the dogs also changed. Familiarity breeds love. Mari was getting older and his red coat grizzled with white flecks. Sometimes, after a strenuous day’s work, they just lie around close to the house, resting. They look at us now and then, but without interest. However, the fact that they rest at Cheetal Walk for extended periods, 100 m. from us, is a testimony that we could as well be trees or rocks for them, a part of the landscape.

These beautiful and mysterious creatures have been totally misunderstood. Our forefathers made the mistake of believing that they were motivated by the same intentions as humans – greed; and judged severely as they were suspected of being a reflection of human nature.

Some interesting references on the dhole:

Acharya, B. B., Johnsingh, A.J.T. and Sankar, K., 2010. Dhole telemetry studies in Pench Tiger Reserve, Central India.

TelemWildl Sci, 13, 69-79.

Davidar, E. R. C., 2012. Whispers from the Wild: Writings by E. R. C. Davidar (Ed. Priya Davidar). Penguin Books, India Pvt. Ltd.

Fletcher, F. W. F., 1911. Sport on the Nilgiris and in Wyanad. MacMillan & Co., London, U.K.

Volodina, E. V., Volodin, I. A., Isaeva, I. V. and Unck, C., 2006. Biphonation may function to enhance individual recognition in the dhole, Cuon alpinus. Ethology, 112, 815-825.

Dr. Priya Davidar retired as a Professor in Ecology and Environmental Sciences, from Pondicherry University. She received her Ph.D. in Zoology (Field Ornithology) from Bombay University in 1979 under the guidance of Dr. Sálim Ali and carried out postdoctoral research in the U.S. She is based in the Sigur region at the foothills of the Nilgiris surrounded by elephants and a tiger named Vlad the Bad. She is active in the field of conservation, both advocacy and research.