The Frozen Ark

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 36

No. 4,

April 2016

By Purva Variyar

It all started with the helplessness and despair over dying snails. Within a short span of 15 years a remarkable polymorphic species of the land snail Partula that was found on the Polynesian Society Islands in the French Pacific by Professor Bryan Clarke, Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS), his wife Dr. Ann Clarke and some other colleagues, began to die out in the hundreds. What was to be a study of these snails, turned out to be a study of extinction. A plan to introduce two alien snail species went disastrously awry. An intensive captive breeding programme was initiated of Partula snails brought to the London Zoo, and their tissue samples were frozen in order to preserve their DNA, so that the study could continue. This was the beginning of what would eventually become the Frozen Ark Project.

Extinction on Speed Dial

The Earth, today, sadly is looking at one of the biggest spates of extinctions in its history, at a severely accelerated rate,all thanks to the ever-increasing human population (we have crossed the seven billion mark; Earth is equipped to sustainably accomodate only two billion) and merciless habitat destruction.

Undoubtedly, dedicated people all over the globe are working to preserve and protect our wildernesses and the life they sustain. But these efforts cannot keep pace with the rate of destruction. It is expected that almost 30 per cent of all land, freshwater and marine animals will go extinct within the next 50 to 60 years. And along with them, millions and millions of years worth of evolution and biological information that crafted these amazing animals will be lost.

Every single organism is a manifestation of the blueprint of information stored in the amazing, microscopic double helical structure within the nucleus of our cells - the Deoxyribonucleic Acid, or DNA. A single DNA molecule inside a single cell comprises all the information and specifications of that entire animal. Given the dismal scenario, scientists have been advocating the idea of collecting tissue and cells of various animals and keeping them frozen for long-term preservation. Several museums, university laboratories and zoos have banks of cells, gametes, tissues and DNA, that is mostly for the purpose of research. However, in the past, these collections were not preserved well enough for long-term survival of undamaged DNA. Also, there was no systemised forum to have all of the samples together in one dedicated space.

A decade ago, Professor Bryan Clarke, Dr. Ann Clarke, and well-known embryologist, the late Dame Ann McLaren, FRS, were struck by how no project to accumulate, and preserve the frozen tissue samples of specifically endangered species was in place anywhere in the world. They decided to undertake this mission and founded the Frozen Ark Project. The project was set up as a registered UK charity at the University of Nottingham, which very graciously provided the required offices, laboratory space, computers and bioinformatics support pro bono since its conception. This not-for-profit independent charity is now a growing consortium with 22 members, including five in the U.K., two in the U.S., and more in Germany, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, Norway, Ireland and India. More countries wait in the pipeline.

Photo Courtesy: Frozen Ark Project.

Is this the Answer?

Biotechnology is growing by leaps and bounds, and the preserved DNA of the frozen samples of tissues and cells could perhaps one day pave the way to be able to revive a species from the dead. The technology and expertise required for this, though on the horizon, is still a long way off. The fascinating property of DNA of being extremely stable, when stored at a cold enough temperature makes it possible to even conceive of all this. And using the principle of polymerase chain reaction (PCR), DNA can now be very easily and quickly copied. In fact, it can be copied indefinitely, ensuring its immortality.

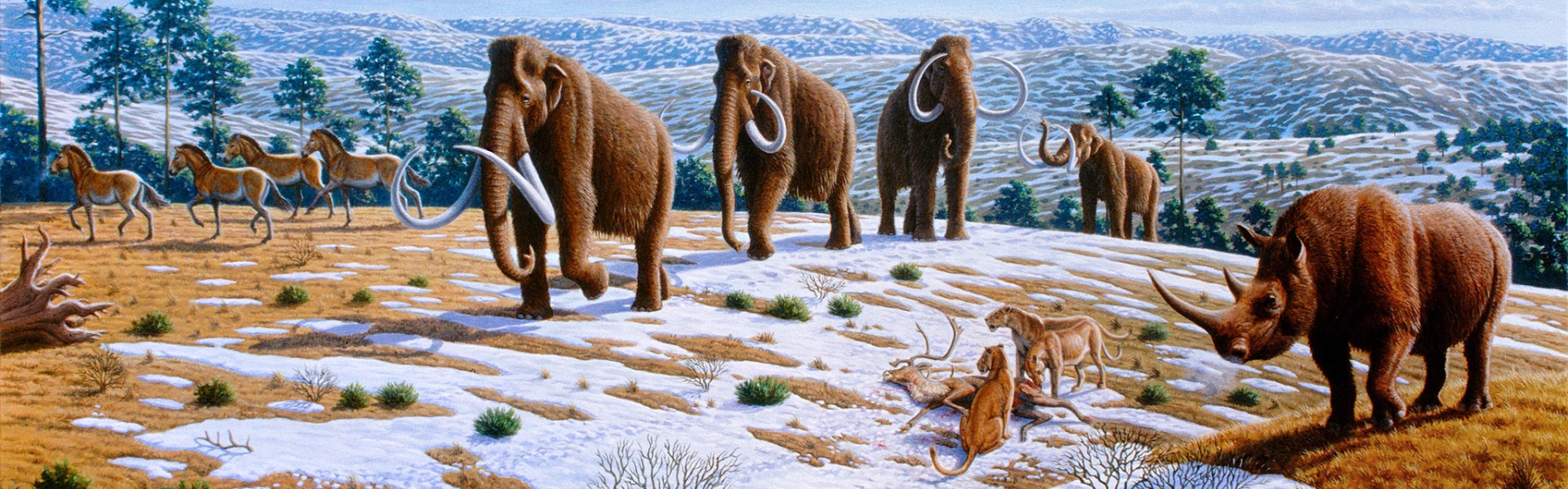

However, is this ethical? Will this be a sanction to let animals go extinct so we can revive them in the future? Take the example of the 40,000-year-old woolly mammoth fossil unearthed intact early last year. The body was so well preserved that fresh blood was found within its muscle tissue, and hopes of cloning it were put forth. Scientists are now working towards further advances to be able to clone this furry giant. But the extremely difficult job of sequencing its genome is the first step which is bound to take a very long time. Dr. Tori Herridge, a palaeontologist at the Natural History Museum, London, who is an expert in mammoth anatomy, has said: “The most fundamental step and ethical concern with this kind of procedure is that you need to have an Asian elephant surrogate mother at some point; cloning a mammoth will require you to experiment on probably many, many Asian elephants." She added: “The most important thing is how much we can learn without having to go down the route of cloning." Dr. Herridge questioned “whether or not the justifications for cloning a mammoth are worth the suffering, the concerns of keeping an elephant in captivity, experimenting on her, making her go through a 22-month pregnancy, to potentially give birth to something which wont live, or to carry something which could be damaging to her. And all of those aspects... I dont think that they are worth it; the reasons just arent there."

At Frozen Ark, they believe that, with technology that is developing so rapidly, you never know, what could be possible in the future and that should be left for future generations to decide. But without preserved genetic samples of endangered animals, nothing can be possible. So far, about 48,000 genetic samples from over 5,000 species have been preserved by the consortium members of the Frozen Ark Project. All the species on the IUCN Red List are being specifically targeted to collect and preserve their tissue samples. But the need is not restricted to just mammalian species. Corals are fast degrading and disappearing, amphibians are the worst hit of any group of animals, and invertebrate populations are seeing a massive decline in numbers.

The Frozen Ark Project today has eight directors on its board and an advisory committee comprising individuals from scientific institutes, zoos, university biology departments, vet schools and natural history museums. The charity is engaged in managing the project, raising funds, creating databases of the preserved samples, establishing expert groups and recruiting new members to the consortium.

Photo Courtesy: Frozen Ark Project.

There is no substitute for conserving species and their integral ecosystems in the wild. The Frozen Ark does not look at its mission and vision as an alternative to protecting and preserving animals within their natural environments. It is a conservation effort of the last resort, an insurance policy or a backup, if you will. It may also help to maintain the diversity of the genetic pool in cases where a particular species might be too inbred to survive. Every single species forms a vital link in the vast fabric of our ecosystem. The loss of any species is a tragedy, in that not only do we lose something so beautiful, but also a treasure trove of information, accumulated over millions of years of life on Earth is lost, forever.

Taking a small sample of tissues or cells from an animal then does not seem futile or a waste. The costs are relatively cheap and the cost of sequencing DNA is dropping. It would take a space equivalent to only a small house to keep the genetic samples taken from all of the worlds species.

Wildlife conservation is a many layered and multifaceted objective. Every perspective, every effort, every thread of thought that goes into it matters and counts. The Frozen Ark Project is one of its kind, and needs to be appreciated and counted on as an important tool for the conservation efforts of tomorrow.

Purva Variyar is a conservationist, writer, and editor. Her true passion lies in science communication. She currently works with the Wildlife Conservation Trust. Purva has previously worked as a Senior Editor and Science Communicator with Sanctuary Asia magazine. She has also worked on human-snake conflict mitigation and radio-telemetry of Russell’s vipers under The Gerry Martin Project.

First published in Sanctuary Asia, Vol. 35 No. 2, February 2015.