The Oil Palm Paradox

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 42

No. 2,

February 2022

By Umesh Srinivasan

Oil palm expansion in India should not – and need not – come at the cost of natural habitats

As someone studying how forest degradation impacts biodiversity in India, for a long time I was blissfully unconcerned that oil palm plantations would destroy the country’s natural habitats. The expansion of oil palm, while certainly concerning in the global context of forest loss and climate change, fundamentally felt like someone else’s problem (namely that of Indonesia and Malaysia).

Until suddenly, it was ours too. Almost overnight – or so it seemed to me – oil palm plantations were mushrooming all over the country. A plant I had never seen in the flesh just six or seven years ago was now seemingly popping up everywhere – southern Karnataka, interior Andhra, the foothills of the eastern Himalaya in Arunachal Pradesh. Disquieting reports emerged that entire districts in Mizoram had been designated as “oil palm districts”. My immediate reaction, all too common amongst tropical biologists, was visceral – what business does this plant have coming into India and threatening our forests?

_C-1700_1643798252.jpg)

A conceptual illustration of a clouded leopard in Northeast India’s verdant, biodiverse forests gazing at a future similar to that of species such as the Bornean orangutan, whose rainforest habitat has been destroyed by oil palm cultivation. Photo: Artists with Animals.

For the sheer scale and enormity of its drastic impacts on tropical biodiversity, perhaps no plant is as widely reviled as the oil palm and no vegetable oil as villainous as palm oil. Paradoxically though, the oil palm’s notoriety is one that is at the same time both deserved and undeserved.

Palm oil – the oil extracted from the fruit of the oil palm – is an exceptionally versatile oil that finds use in a mind-boggling array of products. Not just as one of the most commonly-used cooking oils, but also in soaps and cosmetics, candles, chocolate, biscuits and ice cream. It would be safe to bet that any product with a label listing ‘vegetable oil’ amongst its ingredients has palm oil in it.

Native to west-central Africa, the astonishing yields of vegetable oil that the plant can produce have ensured its steady march in the form of forest-destroying plantations across the tropics – especially in Southeast Asia, but also increasingly in Latin America and the rest of Africa. A massive 40 to 70 per cent of the area under oil palm in Indonesia and Malaysia (about 20 million ha.) has directly replaced some of the most biodiverse primary rainforests in the world, home to critically endangered species such as the Bornean orangutan and the Sumatran tiger. Monoculture plantations of oil palm are completely devoid of biodiversity – the minuscule number of species that manage to eke out a living in oil palm plantations such as the Red-vented Bulbul and the Common Tailorbird, are those uber-generalists that can withstand the most degraded landscapes that humanity can conjure up. No wonder then that the plant has a bad rap.

But to blame the oil palm itself would be a mistake. The plant itself has no agency. It cannot transport itself across continents, cut and burn down forests and then replicate itself across millions of hectares of rank-upon-rank of evenly spaced individuals begging for water, fertilisers and pesticides. At the risk of stating the blindingly obvious, humanity has selected the oil palm for extensive cultivation because of its prodigious yields and then – dismissing biodiversity conservation and climate concerns – decided to grow oil palm at the expense of highly diverse natural habitats, mostly tropical forest. The unquestioning hatred that the oil palm often evokes is therefore perhaps a little unfair.

Palm oil plantations are one of the leading causes of decline in orangutan populations. Vast tracts of virgin rainforests – essential for orangutan survival – have been cut down and replaced with oil palm trees. Photo:Thomas Vijayan/Sanctuary photolibrary.

Threats to a Biodiversity Hotspot

White-winged Wood Duck. Photo: Soham Das.

White-winged Wood Duck. Photo: Soham Das.

India’s Northeast is one of the most biodiverse on the planet, ranking alongside the Amazon-Andes in South America and the Eastern Arc Mountains of Africa. For any taxonomic group – fungi, plants, invertebrates, amphibians, reptiles, birds or mammals – Northeast India consistently emerges as a biodiversity hub. It also includes parts of two Global Biodiversity Hotspots, the Himalaya and Indo-Myanmar. Global Biodiversity Hotspots are not only exceptionally rich in species, but are also exceptionally threatened. Northeast India’s fantastic diversity, therefore, is already besieged. There is the danger that oil palm, which can only be grown in the low elevation foothills of the largely hilly northeast, will replace the few remaining tracts of lowland tropical rainforest and grassland in the northeastern states. These lowland areas are crucial habitats and corridors for a diverse range of wildlife, including threatened species such as tigers, elephants, hornbills and lowland-restricted species such as the White-winged Wood Duck and Bengal Florican.

India’s Plan

The oil palm is a fantastic plant. Per hectare, an oil palm plantation produces six to 10 times as much oil as the next most productive oil crops such as rapeseed, soy or sunflower. Oil palm therefore gives us the option to produce as much vegetable oil in six- to 10-fold less land area than any other oil crop. The oil palm’s stellar productivity – the very reason for its global takeover of tropical oilseed cultivation – is also a marvelous opportunity. By growing oil palm – intelligently, carefully and in the right areas – we can satisfy our demand for vegetable oil while sparing vast areas of the most biodiverse forests on the planet that might otherwise have been destroyed to grow soybean or sunflower. No other oil crop comes even close to presenting us with such a win-win option.

It is emphatically now that India, about to take the leap into extensive oil palm cultivation, must leverage the massive productivity of the oil palm plant to both attain domestic security in vegetable oil production and spare what remains of our natural habitats. India is by far the largest consumer of palm oil globally, accounting for over 20 per cent of the palm oil used worldwide. However, even as of today, India imports a colossal 99 per cent of its palm oil, largely from Indonesia and Malaysia. (In a sense, therefore, India – not producing its own palm oil – imports the oil while “exporting” the harmful environmental, socio-cultural and labour impacts of its enormous demand to south-east Asia. It is this massive shortfall in production that has prompted the government’s push for vegetable oil security under the banner of the National Mission on Edible Oil-Oil Palm (NMEO-OP).

Palm oil plantations seem to have sprung up overnight in many parts of India including the Northeast, replacing biodiversity-rich forests. Photo: Gaurab Talukdar.

The NMEO-OP is an ambitious undertaking that aims to place (an additional) 1.32 million ha. of land under oil palm cultivation in India by 2030. This is about three-and-a-half times the size of Goa. While the motivation behind the NMEO-OP appears clear and reasonable, there is still cause for major worry.

The NMEO-OP identifies Northeast India and the Andaman and Nicobar Islands as priority areas for oil palm cultivation. Both these regions together encompass three Global Biodiversity Hotpots, host multitudes of species that are globally threatened, range-restricted or endemic, and continue to retain the most vast forest tracts in India. These forests are not only crucial for biodiversity, but also for climate resilience, indigenous lifestyles and livelihoods. It is difficult to conceive of establishing oil palm plantations in these areas without cutting down and replacing existing forests, as has already happened in some northeastern states, primarily Mizoram. To my knowledge, oil palm plantations are currently present and being expanded in lowland areas of Arunachal Pradesh (Lower Siang, Lower Dibang districts, amongst others), Nagaland, Mizoram and parts of Assam. Of all the forested habitats in Northeast India, the low elevation dipterocarp dominated tropical rainforests are perhaps the most threatened. Large areas that historically had such habitats have now come under permanent agriculture and settlements. These are also habitats vital to endangered species such as hornbills, tigers and elephants. This is something that India simply cannot afford to do – and in fact, need not do.

The kernel or nuts of the bright orange fruit are used to extract palm oil. The oil is used in manufacturing a range of edible products. Photo: Public domain/Ricky Martin.

A Suitable Land

First, maps of suitability for oil palm in India published by the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) show that most areas of Northeast India are bio-climatically unsuitable for oil palm cultivation (except southern areas of Tripura and Mizoram). Oil palm is adapted to temperatures between 220C and 330C, and requires about 2,500 to 4,000 mm. of relatively even rainfall throughout the year. Monsoonal Northeast India, with the majority of its rainfall concentrated in about four months of the year and with temperatures dipping well below 220C, is not the natural bioclimatic envelop in which the oil palm plant thrives. Replacing forests with oil palm in Northeast India might therefore not increase domestic production in the long run, particularly if oil palm plantations in the region fail… a distinct possibility.

Second, as a recent paper ‘Oil palm cultivation can be expanded while sparing biodiversity in India’ published in Nature Food suggests, India has up to 38.8 million ha. of land, potentially available for oil palm without even touching any of its existing forests and natural habitats such as our peninsular grasslands. This 38.8 million ha. of land is the overlap between areas suitable for the cultivation of oil palm (under a scenario of climate change and the use of ideal agricultural inputs including irrigation) and existing cropland. In this massive area, the existing crops currently being grown vary from region to region, with rice in many areas and other crops such as cashew in parts of coastal Maharashtra and Goa. Replacing a fraction of the existing crops in this vast area with oil palm will go a long way in ensuring enough vegetable oil production without compromising our biodiversity or food security.

A Global Reputation

Photo: Public Domain/Ricky Martin.

Photo: Public Domain/Ricky Martin.

By a large margin, the largest current producers of oil palm in the world are the southeast Asian nations of Indonesia and Malaysia. In both these countries, oil palm plantations have largely been expanding by cutting down and burning biodiversity-rich tropical rainforests and habitats such as peat swamp forests that are also crucial for carbon sequestration. Given that almost every product that contains vegetable oil (from soap to biscuits) has palm oil, shoppers across the world are increasingly concerned about the ramifications of their consumption of a wide variety of products on tropical deforestation, and on land rights and the human rights of oil palm plantation labourers. The Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) does lay down guidelines for the fair and sustainable production of palm oil, but the real-world impact of the RSPO has been mixed at best.

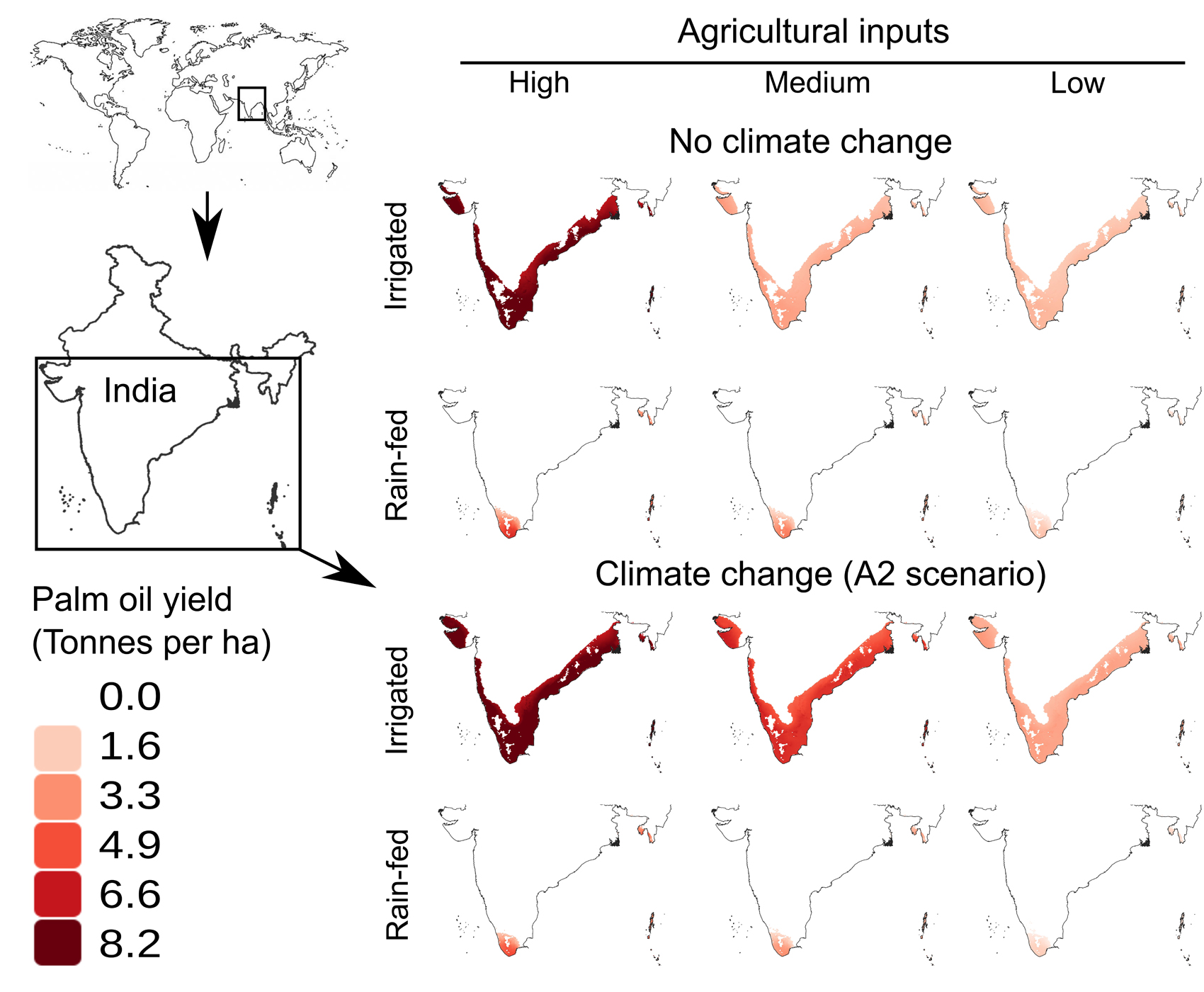

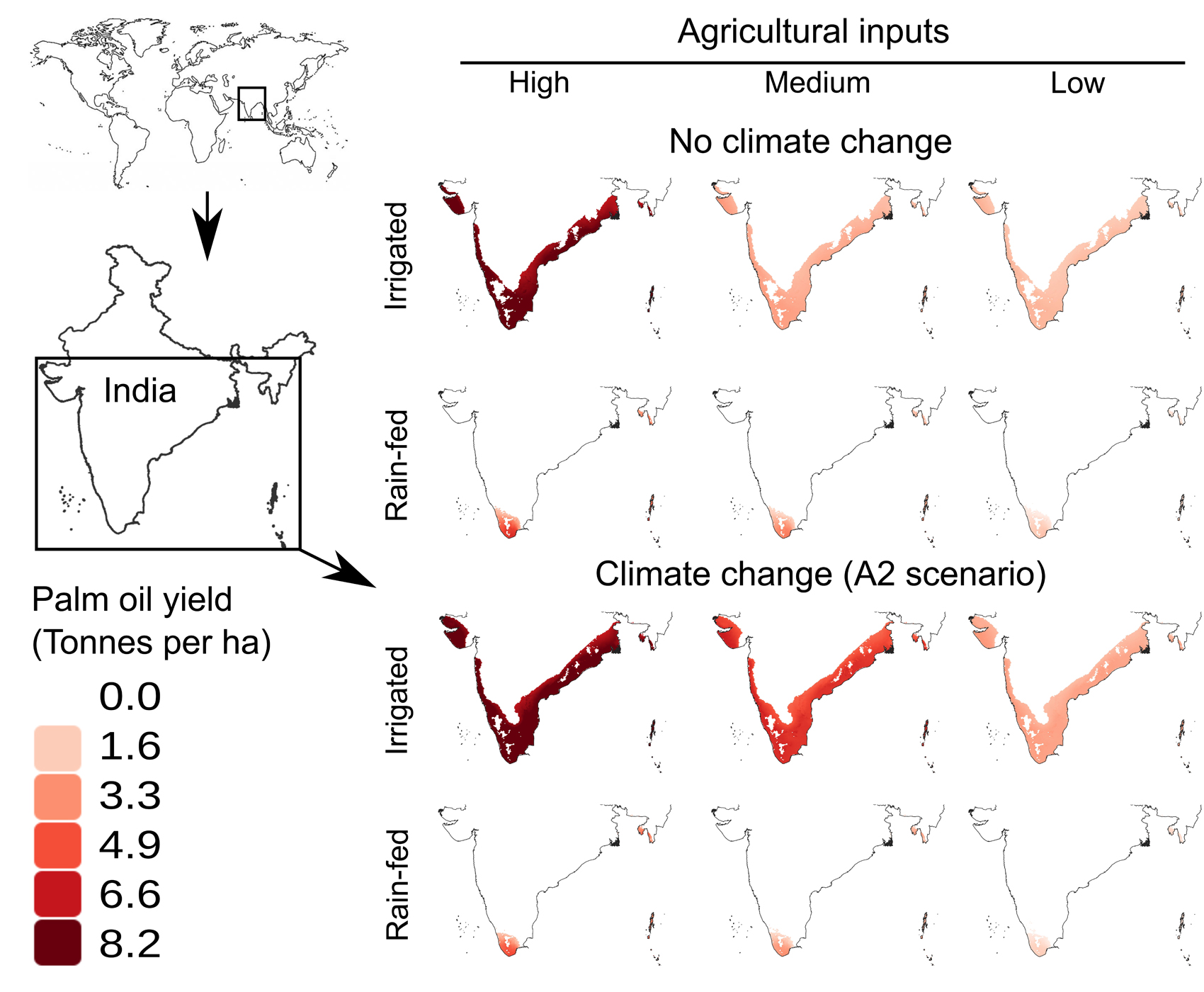

Areas biophysically suited to the cultivation of oil palm in India under differing scenarios of climate, irrigation and agricultural inputs, with corresponding yields. White regions represent areas unsuitable for the cultivation of oil palm.

Photo Courtesy:Umesh Srinivasan

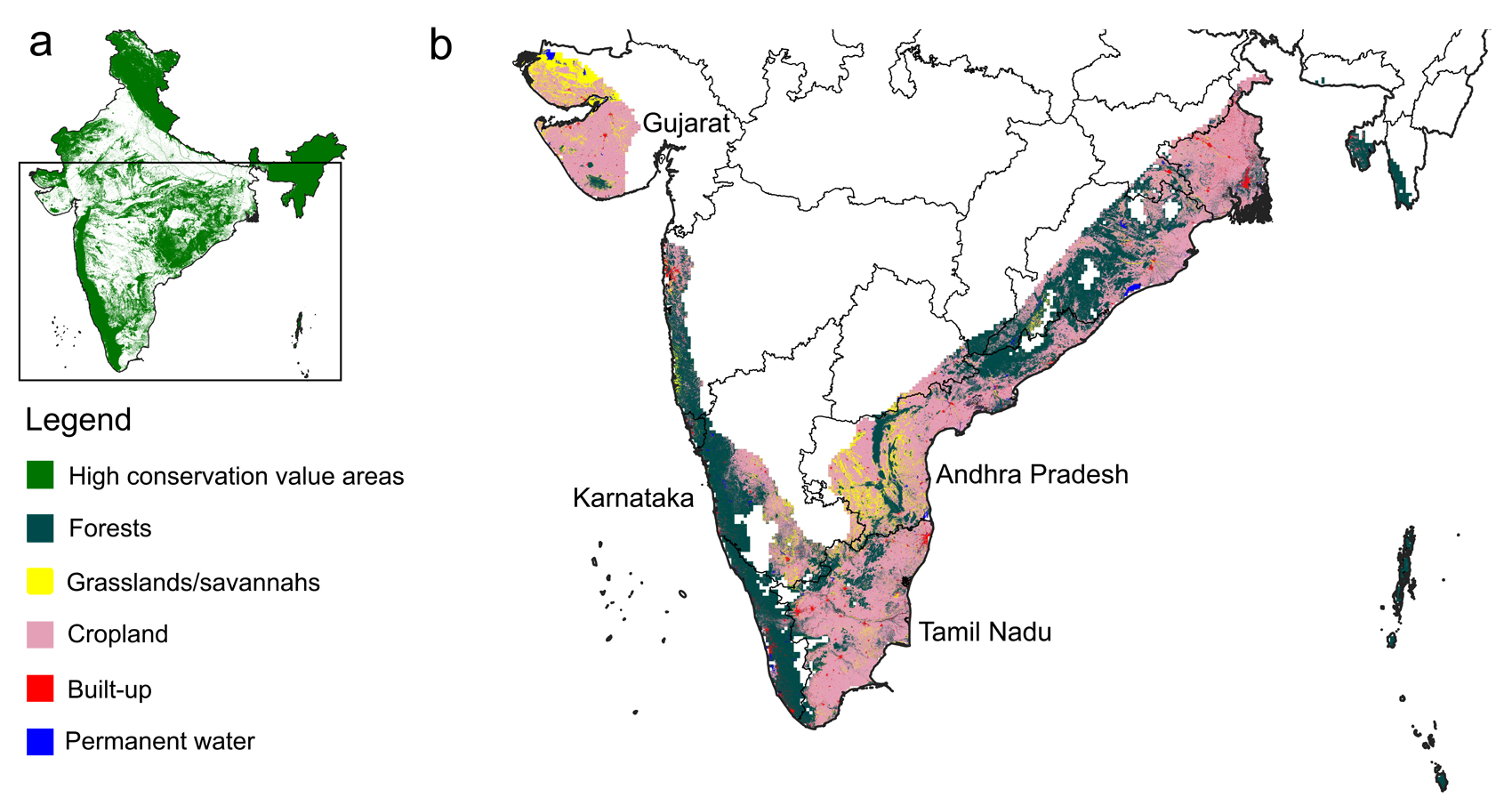

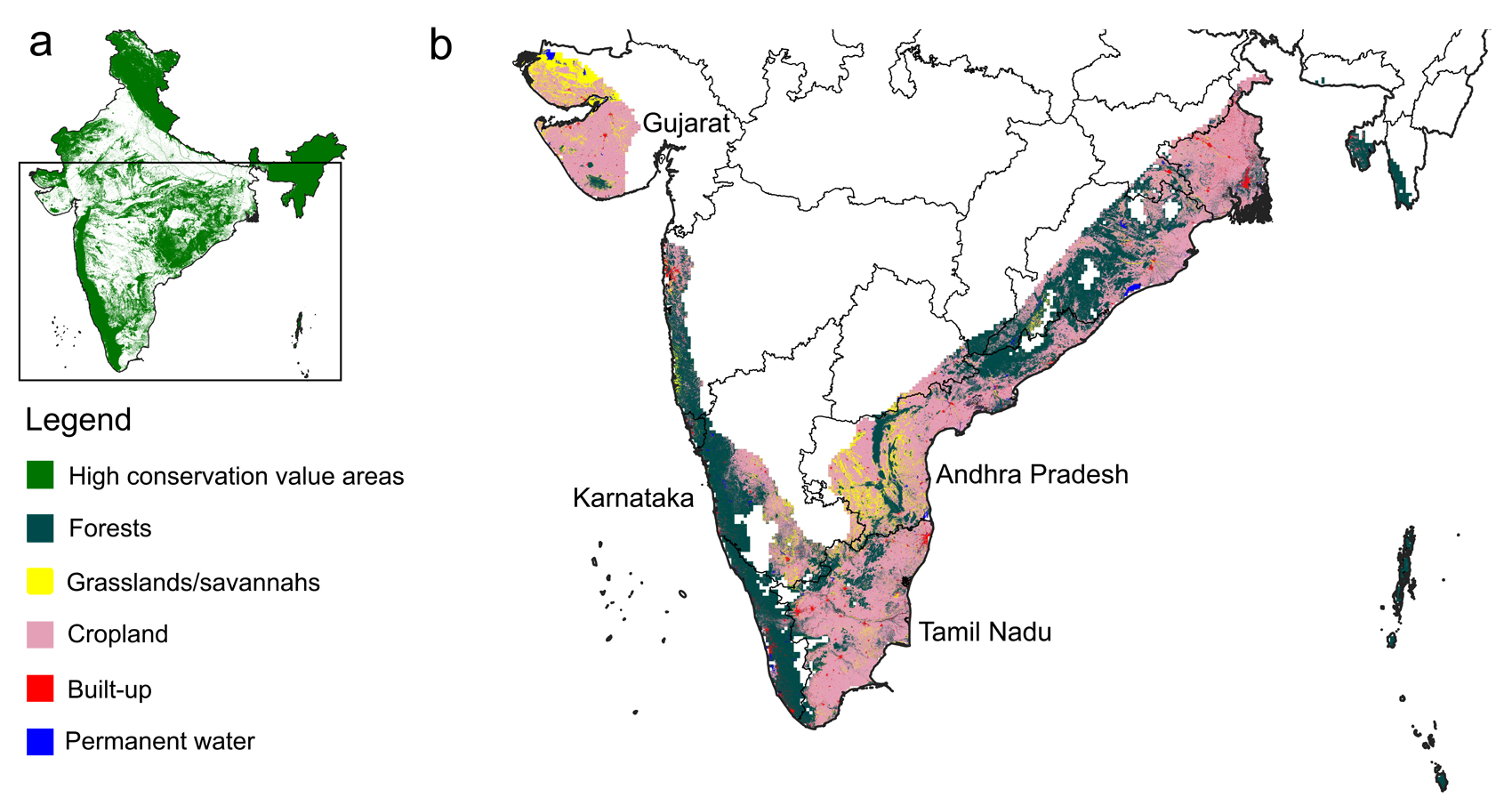

(a) High conservation value regions of India include all remnant natural forest and savannah grasslands, existing Protected Areas and the entire area within global biodiversity hotspots irrespective of land use/land cover. (b) Land use/cover under the area suitable for oil palm cultivation (under the A2 climate scenario), with artificial irrigation and high agricultural inputs, consists of natural habitats (forests and savannahs) as well as large areas of existing cropland. White regions are unsuitable for oil palm cultivation. Boundaries of Indian states are shown with solid black lines. See also Figure 1. Photo Courtesy: Umesh Srinivasan.

A Brief History of Palm Oil in India

The idea of growing oil palm in India is not new. India’s Oil Palm Development Programme dates back to 1991 and the Special Programme on Oil Palm Area Expansion (2011) offered farmers hefty subsidies on saplings, fertilisers, pesticides and irrigation to encourage a switch to oil palm. The uptake however, was slow and mainly in southern states such as Andhra Pradesh, which continues to be the largest producer of palm oil in India. In Northeast India, on the one hand, Mizoram embraced oil palm enthusiastically, with the state’s New Land Use Policy (NLUP) officially encouraging the replacement of “wasteful” shifting cultivation with oil palm plantations. On the other hand, Manipur has been wary of oil palm, with indigenous groups concerned about threats to traditional and ecologically sustainable land management practices. The new national mission, the NMEO-OP (2021), shifts the emphasis on oil palm cultivation to Northeast India and the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, both highly biodiverse regions with important cultural linkages between forests and indigenous peoples.

Regional Planning

Further, while palm oil production targets aimed at enhancing domestic vegetable oil security might necessarily be a national-level priority, actually planning new oil palm plantations on the ground must be a regional exercise. In a country as geographically and culturally vast as India, the dictates of climate, availability of irrigation, transportation and milling infrastructure, land tenure systems and biodiversity considerations vary greatly from place to place. Successful oil palm plantations – and we must count the non-replacement of biodiversity-rich landscapes as an essential criterion for success – will be those that take all of these and other local-scale contingencies into account.

An oil palm plantation in Zawlteram in Mamit district of Mizoram, juxtaposed against a biodiversity rich mountain range does not make a pleasing sight. Photo: Gaurab Talukdar.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, preserving our natural habitats should be absolutely non-negotiable in the current era of rapidly accelerating climate change. Monsoonal India is set to be one of worst-hit regions in the world by extreme climate-driven events such as super-strong cyclones, massive floods and severe droughts. The past year has been a grim reminder of this, and scientific consensus is that extreme weather events will become both more frequent and more intense than ever before. We will need all the forests and natural habitats we have to buffer us against such extreme events – forests to soak up extreme rainfall and prevent floods and then to release water through the year to prevent droughts.

Erratic weather conditions, increased severity of typhoons and cyclones resulting in massive floods are clear indicators that India needs to safeguard and strengthen its last-remaining biodiverse forests. Photo: Public domain/Anil Gulati.

India is in a truly unique position with respect to its oil palm cultivation. At this very early stage in our own oil palm boom, we have masses of evidence from the exceptionally well-studied Indonesian and Malaysian misadventures from which to learn. To repeat Southeast Asia’s oil palm mistakes at home would be nothing short of a tragedy. Under the aegis of the NMEO-OP, India also has the opportunity to design a transparent and evidence-based oil palm policy that ensures that natural and semi-natural habitats across the country are left completely untouched by oil palm’s ubiquitous hand. India’s oil palm plan is precariously poised. We could either end up as yet another tragedy in the long list of countries that have destroyed their last-remaining wildernesses for sterile monoculture plantations, or we could choose to be a global example of sustainable oil palm production for tropical countries across the world that will almost inevitably succumb to the charms of the oil palm.

Umesh Srinivasan An Assistant Professor at the Centre for Ecological Sciences, Indian Institute of Science, he studies the impacts of climate change and habitat loss on Northeast India’s biodiversity.

_C-1700_1643798252.jpg)