The Public Health Perils of the Etalin Hydroelectric Project

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 40

No. 6,

June 2020

By Sidharth Singh

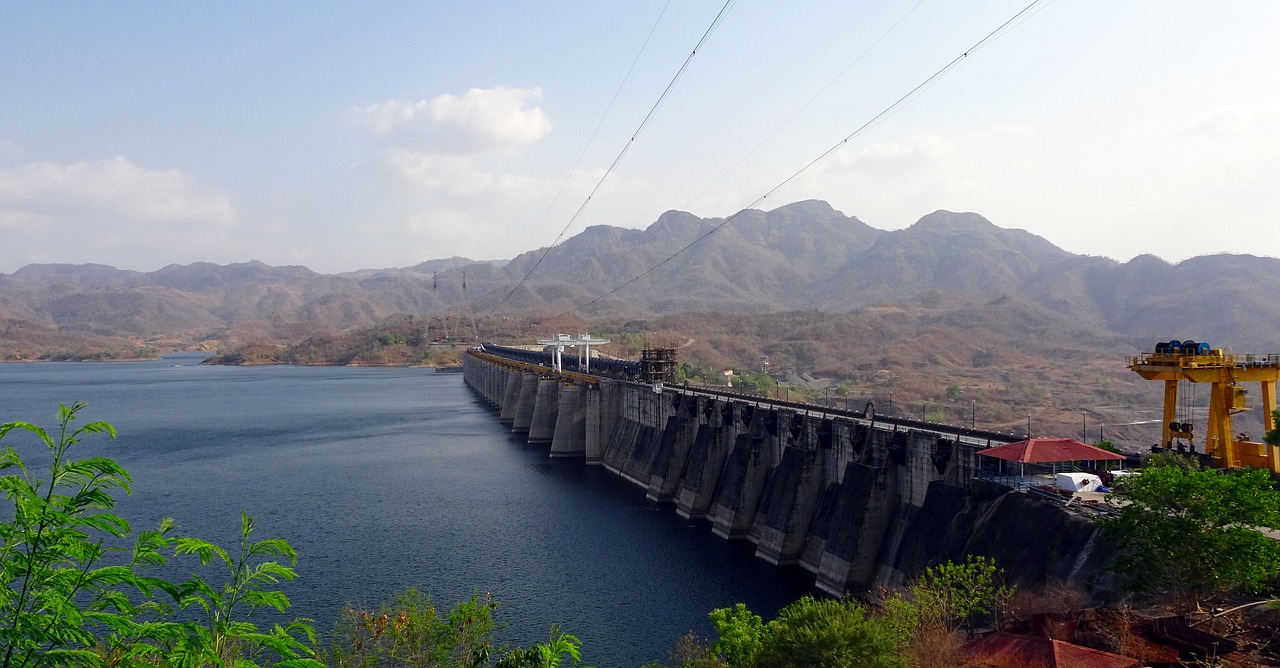

The Etalin Hydroelectric Project, a joint venture of Jindal Power Limited and the Hydro Power Development Corporation of Arunachal Pradesh in Dibang Valley district, has been on halt for the past six years. The Forest Advisory Committee (FAC) reviewed the pending clearance for the 3097-megawatt project on April 23, 2020, the 30th day of the nation-wide lockdown, renewing a long-standing controversy about large hydro-projects in the region. The FAC deferred its decision on the project, instead asking the Ministry of Power for comments on the economic viability of the undertaking.

Much of the controversy over these past six years has been driven by the severe environmental consequences of the Etalin project. The project requires diversion of 1155.1 hectares of biodiversity-rich community forestland, and the felling of 2,78,038 trees, putting at risk up to 555 species of birds, 60 species of mammals, 48 species of amphibians, and 381 species of butterflies, among several others in this rich biodiversity hotspot. One must also note that the 2,880 megawatt Dibang Multipurpose Project (DMP) is to be built on the same network of rivers in the Dibang region. A budget of 1,600 crores was approved for “pre-investment activities” for this project by the Cabinet Committee on Economic Affairs, Chaired by Prime Minister Narendra Modi in 2019. The completed dam of DMP, at a height of 278 m., will be the tallest concrete gravity dam in the world.

Despite the current coronavirus pandemic, and the FAC’s deliberations in the midst of a health crisis, the public health risks of hydro projects such as the Etalin HEP ironically remain ignored. As far back as the year 2000 the World Health Organisation (WHO) made a submission to the World Commission on Dams that stated, “health considerations should always be included alongside economic, environmental and social issues in decision making on dams.” Yet public health continues to remain a neglected issue when it comes to dam construction.

Risking Malaria, AIDS, and Zoonotic Diseases

Amidst a host of dam-related public health consequences including HIV/AIDS, cholera, and schistosomiasis, the WHO document also listed an increased incidence of malaria. Obstructing the flow of a river and creating a large reservoir of standing water makes the riverine ecology of a landscape lake-like, enabling the spread of vector-borne diseases such as malaria.

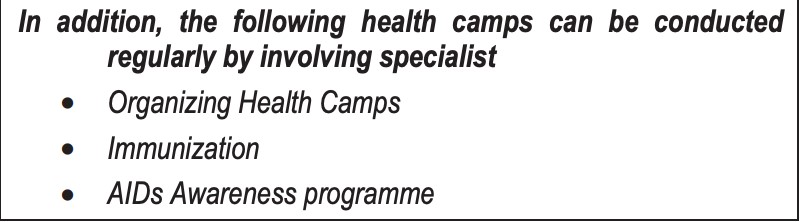

India already has a history of large hydro projects causing intense outbreaks of water-borne diseases. For instance, the Indira Gandhi Nahar Pariyojana, India’s longest canal, diverted waters from the Sutlej and Beas rivers of the Himalaya, into the Thar Desert of Rajasthan. The resulting ecological changes led to new prospects of agriculture, new settlements, and subsequently, new breeding grounds for swarms of mosquitoes, leading to a spell of deadly outbreaks of malaria.

“No doubt the mosquitogenic potential of the command or irrigated area [of the Etalin HEP and even Dibang Multipurpose Project] would be increased,” Dr. Ashwani Kumar, entomologist and director of the Vector Control Research Centre at the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR), told this writer in a written statement.

According to Dr. Kumar, it is the seepage along the margins or shoreline of hydro-projects, such as Etalin HEP or the canal system linked to dams such as Dibang Multipurpose Project, which are potential breeding grounds for mosquitoes. He said, “The potential of breeding of mosquitoes is generally low in the main body of the dam due to the presence of a variety of native species of larvivorous fish (fish that eat mosquito larvae). Mosquitoes do not prefer to breed in the main body of the dam.”

The Indira Gandhi Nahar Pariyojana diverted waters from the Sutlej and Beas rivers into the Thar Desert of Rajasthan; this resulted in causing new breeding grounds for mosquitoes and deadly outbreaks of malaria. Photo: Shivender Singh/ Public Domain.

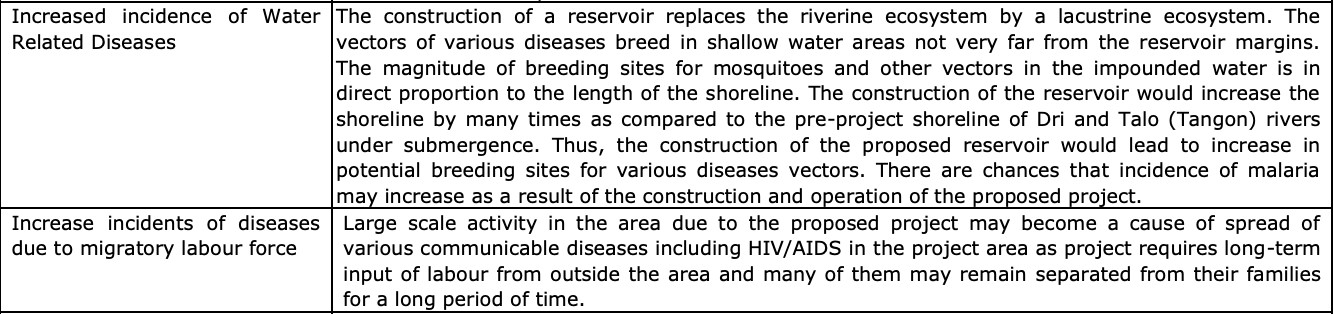

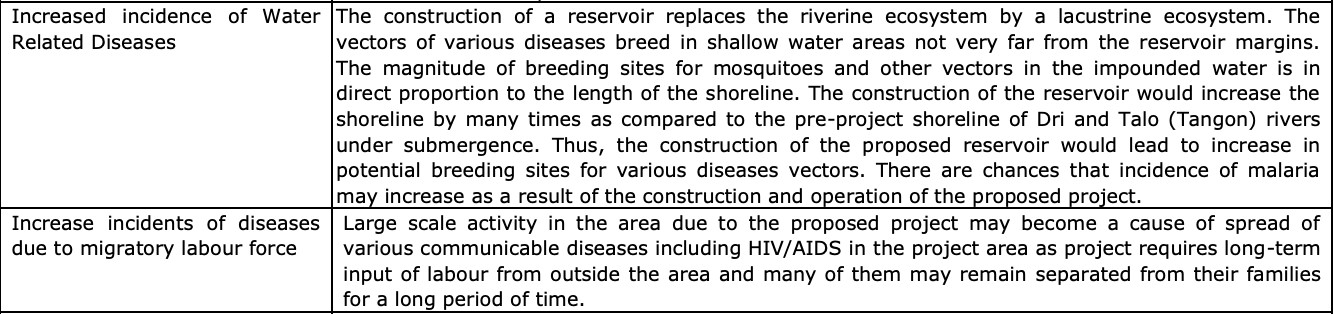

Notably, the health risks of Etalin HEP have been mentioned in varying capacities in its two Environmental Impact Assessments (EIA) conducted by RS Envirolinks Technologies Private Limited in 2015, and the Wildlife Institute of India (WII) in 2019.

RS Envirolinks has highlighted public health issues in some sections of their report. In one such section, the report states, “there are chances that incidences of malaria may increase as a result of the construction and operation of the proposed project” and even that “the proposed project may become a cause of the spread of various communicable diseases including HIV/AIDS.”

An excerpt from page 8.17 of the RS Envirolinks EIA in 2015. There are multiple such sections in this EIA.

An excerpt from page 8.17 of the RS Envirolinks EIA in 2015. There are multiple such sections in this EIA.

Large-scale construction projects such as the Etalin HEP lead to outbreaks of AIDS because they require a large force of migrant workers who are away from families for extended periods of time, which in turn creates suitable conditions for sex work. The construction phase of the Etalin Project is seven years, which is a conservative projection given the track record of delays to such projects in the northeast. The Environmental Impact Assessments of the project have mentioned the requirement of an approximately 12,000 strong migrant labour workforce.

This is especially noteworthy as there is already a growing epidemic of AIDS in Arunachal Pradesh. In February this year, the Arunachal Pradesh State AIDS Control Society (APSACS) issued a statement saying they had detected 434 positive cases of AIDS in 2019. In a written statement, APSACS told this writer that three of these positive cases were migrant workers.

In their February announcement, APSACS Assistant director Marto Ete is on record to have said, “Their [migrant workers and truckers] living and working conditions, sexually active age and separation from regular partners for extended periods of time predispose them to paid sex or sex with non-regular partners.”

Bringing in a large migratory labour force might also increase the risk of zoonotic transmissions. Migrants living in cramped, unsanitary labour camps built over recently cleared tropical and sub-tropical wet forests—that too the most biodiversity-rich—could be exposed to novel pathogens and parasites.

Bringing in migrant labourers will inevitably increase demand for wild meat, bringing people in increased contact with wild animals and increasing the risks of the spillover of zoonotic diseases.

In remote and biodiversity-rich areas such as Dibang Valley hunting practices and consumption of wild animal meat tend to increase as provisions are made for labour camps, bringing people in increased contact with wild animals. Bringing in a large force of migrant workers would then mean incentivising the kind of wild meat trade that has brought about the current pandemic.

“There are only one-off cases of wild meat being traded right now, there are no wild meat markets as such in the Dibang Valley,” a wildlife expert working in the valley, who chose to remain anonymous, told this writer. “But this is true only because there hasn’t been enough demand. If you put 12,000 new mouths in a place where the supply of wild meat is more easily available than domestic meat, then there is the risk of wild meat demand increasing.”

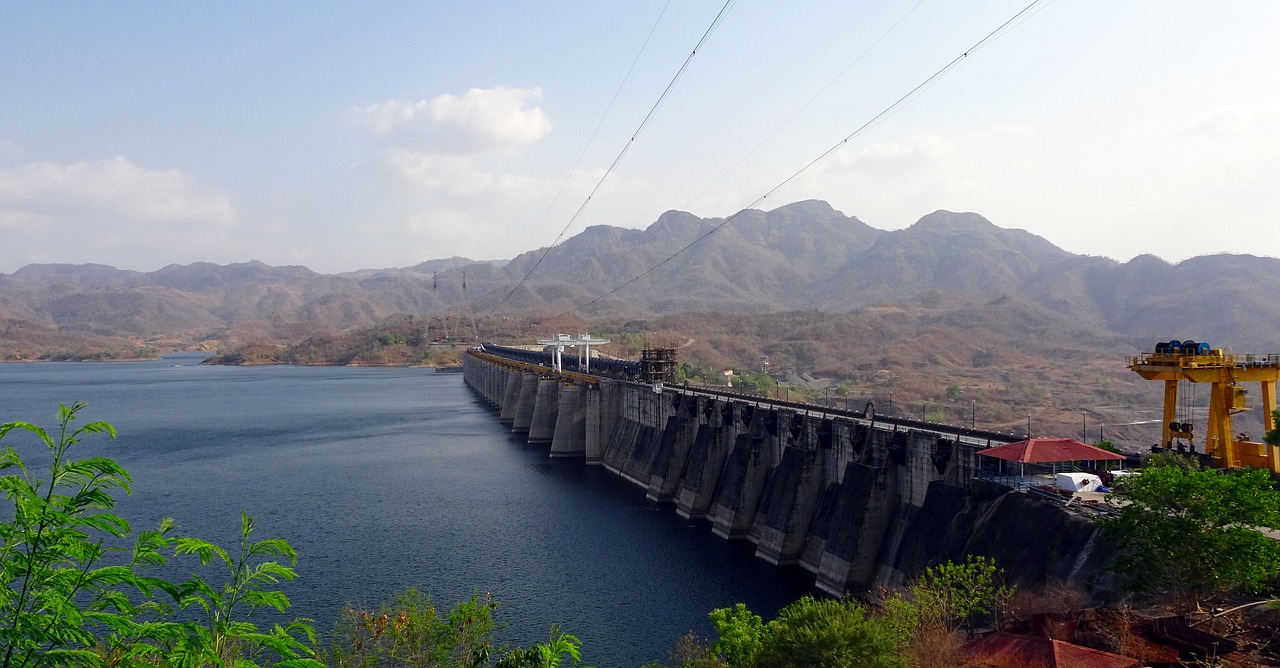

While the RS Envirolinks report made no mention of zoonotic threats, all public health concerns were diluted to near-disappearance in the successive Wildlife Institute of India EIA. The Etalin HEP needed two EIA reports because in 2017 the FAC deemed the RS Envirolinks report “completely inadequate” when it comes to biodiversity, and recommended “multiple seasonal replicate studies on biodiversity assessment by an internationally credible institute.” A new report was prepared by the Wildlife Institute of India, which makes no mention of malaria or zoonoses and makes a single mention of AIDS when it recommends an AIDS awareness programme for “facilitation in health care and education”.

Interestingly, far from detailing public health liabilities, the WII report has repeatedly stated that the project will actually lead to developments in “health and overall enhancement of life quality.” The report made no specific mention of the subsequent diseases the project might cause and discussed health only in a vague ambit of developing healthcare facilities. This is in contradiction not only with the previous EIA of Etalin HEP but also with the general consensus around health and dams.

The WII report has been widely criticised by the scientific community in India. On May 5, 2020 26 scientists released a peer review of the EIA which alleges that “incomplete and inaccurate data lead to an erroneous and inadequate assessment of the impact potential of the proposed HEP on biodiversity.” But even the peer review makes no mention of the WII’s weak and inaccurate dealing with public health consequences.

Excerpt from the WII EIA in 2019. This is the only mention of AIDS, or any disease, in the EIA.

Excerpt from the WII EIA in 2019. This is the only mention of AIDS, or any disease, in the EIA.

The Monuments of Our Ignorance

Given that the coronavirus pandemic is a direct consequence of invading wild habitats, why does public health continue to be absent in the heated debate around the Etalin Project, which would invade the country’s richest biodiversity hotspot, and evidently have immediate public health risks?

While the FAC considers the economic viability of the Etalin HEP in the middle of a pandemic induced lockdown, it is ironic that the project’s dangerous public health consequences of malaria, HIV/AIDS, and possible zoonoses are being ignored.

Dr. Abi Tamim Vanak, a fellow at the Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and the Environment, is a One Health researcher, a multi-disciplinary concept founded on the connected nature of animal, environmental, and human health. “People working in One Health have a popular saying,” said Dr. Vanak, “Healthy environment, healthy animals, healthy people. One cannot look at human health in isolation, especially when it comes to communicable diseases. There is an environmental aspect to it too.”

When asked if public health issues should now be a primary concern when considering the construction of large-scale hydro-projects such as Etalin HEP he said, “Health aspects have always been under-reported and undervalued when it comes to such projects. The value of intact ecosystems needs to be viewed also from a public health perspective and not just an intact ecosystems framework. We need new metrics while evaluating such projects, not just biodiversity loss and carbon footprint. The public health costs are very real.”

Echoing One Health’s interdisciplinary approach, Dr. Kumar said “Since dams are necessary for water, energy and food security, they will bring prosperity to the state. However, to prevent vector-borne diseases, the Irrigation Department and Health Department will have to work in tandem from the inception of the project to prevent outbreaks of vector-borne diseases by taking necessary preventive and control measures in a continued manner.”

Public health issues ought to be a primary concern when considering the construction of large-scale hydro-projects, say experts. Photo: Public Domain.

No such measures seem to have been a concern in the debate around the Etalin Hydroelectric Project. Be it the very real risks of malaria and AIDS, or the possibility of zoonotic transmissions, it is worth stressing that the immediate sufferers of these diseases would be none other than the migrant workers who build the dam, and who have recently suffered one of India’s greatest humanitarian crises, and the local Idu Mishmi community who have a global population of a mere 14,000.

The Etalin HEP will consist of two dams that divert, via underground tunnels, water from the Dri and Talõ rivers. One dam will be 101 m. high and the other 80 m.. These rivers are tributaries of the Dibang river which itself will host the looming 278 m. gravity dam of the Dibang Multipurpose Project. If the public health consequences of large-scale construction projects such as Etalin HEP are not thought about even in the middle of the coronavirus pandemic, such projects may well become the towering monuments of our ignorance in the future. There are currently 15 other proposed hydro-projects in the Dibang basin.

Damming Rivers, Releasing Diseases

By Sakshi Nulkar and Abi T. Vanak

The unintended, and sometimes unforeseen consequences of infrastructure development and rapid land use change can result in deleterious impacts on human health. Dams in particular, can cause large-scale changes in several social, ecological and hydrological factors that can increase the risk of emergence and spread of infectious diseases. The loss of natural habitats due to the construction of the dam and its associated reservoir itself can be highly damaging. However, the associated construction infrastructure, including offices, living spaces and other amenities, that develop alongside such dams can also result in permanent landscape change.

The settlement of large numbers of migrant workers at forest edges not only causes the loss of biodiversity, and often an increase in illegal wildlife hunting, but also tends to disrupt local socio-ecological relationships, with added pressure on local food resources. Such changes can also lead to an increase in populations of generalist species, especially from rodent and primate groups. These two groups, along with bats, account for most of the emerging zoonoses that humans are at greatest risk from.

Poor and often unhygienic living conditions coupled with an increase in stagnant water due to damming of rivers can result in the increase of vector-borne diseases. For instance, in South America, an altered water-flow regime from changing land-use practices influenced vegetation hundreds of miles downstream, leading to a shift in the mosquito community, favouring the population increase of a more efficient malaria vector. Instances like these can never truly be predicted when altering ecosystems drastically, as in the case of the Dibang Valley, where not just Etalin, but a staggering 17 hydro projects are in the works.

In addition to malaria, other deadly mosquito-borne diseases such as dengue, chikungunya, and Japanese encephalitis can also rapidly emerge in such conditions. The increase in density of humans, and the potentially higher incursions into the forested landscapes also puts humans at risk from other vector-borne diseases such as scrub typhus and Kyasanur forest disease. Directly transmitted diseases such as gastrointestinal parasites, leptospirosis, and influenza can also peak. Most worryingly, since the immigrant population is often more susceptible to potentially novel pathogens in these environments, the chances of local outbreaks is also high. Given the highly connected nature of the modern economy, it doesn’t take long for the local to go global.

There can be no generalizations to predict the pathways that lead to the emergence or spread of infectious diseases from the encroachment of highly biodiverse forests. However, the risk to public health is not only limited to the spread of infectious diseases. Human health can be affected by pollution, food insecurity, cramped living conditions, and hazardous working conditions. The larger aim of economic prosperity, improvement in health and lifespan for the nation cannot be fulfilled if the burden of this prosperity is disproportionately thrust upon the “economically poor” sections of the society, and the intact natural systems that they depend on.

Sidharth Singh is a writer, teacher, and independent journalist in Delhi. He is currently an Instructor of Critical Thinking at Ashoka University. Sakshi Nulkar is a research associate at ATREE. She is interested in disease ecology, and understanding parasite-host relationships in wildlife living close to humans. Abi Vanak is Convenor of the Centre for Biodiversity and Conservation, ATREE, and a Fellow of the DBT/Wellcome Trust India Alliance Program.