The Secret Lives Of Himalayan Wolves

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 37

No. 8,

August 2017

By Salvador Lyngdoh

“Chanku is like the wind," said Tsering, referring to the wolf as it is called in Spiti.

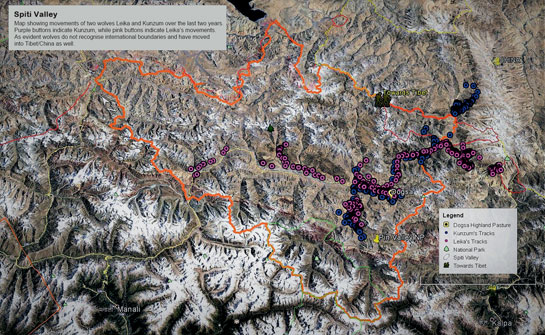

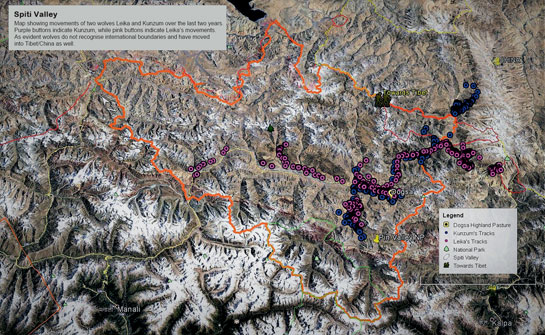

At 5,000 m. above mean sea level, the wind slaps you in the face, and the sun chars your appearance. Initial days may be slow but as you get used to the thin air, you get in the groove and bother less about your tanned face and more about catching your breath. I have been studying wolves in this wondrous landscape for some years now. No doubt, it has been both majestic and challenging, searching for them. Judging from what the La Yul Mis (people of the Land of God) say, they were once more common.

We had chalked out our plan to trek through Kibber, once the highest village in the world, and also part of a wildlife sanctuary by the same name. Tsering has been up and down these mountains many times. He tells me his ancestry lies in Tibet. When he was young, he fell in love and finally settled in Spiti. As he describes his journey through the forbidden kingdom, I can only wonder how vast the Trans-Himalaya really is and what it would have felt like walking amongst the clouds. He has managed to live well by guiding travellers along these hazardous routes for years. He has crossed paths with wolves a few times; they are shy of humans, and prefer to come uninvited, generally away from sight, he says.

Photo: Salvador Lyngdoh.

Nomadic pastoralism has lasted here in the high valley for over a millennium. The Trans has always been a place for pastoralists from the lower hills and mountain mystics alike. I pride myself with a similar quest, not for peace or tranquility, but for a glimpse into the secret life of an intelligent creature, one living near man and yet wild and free.

Our study site

The Spiti catchment area is dominated by agro-pastoralists, who have for centuries lived in harmony with nature. After scouring through miles of never-ending slopes for over a month, I finally heard of confirmed wolf activity in a village not far south of the valley. Sushil, a local tracker, heard of wolves frequenting Mane village. We arrived to discover a quiet, pristine village cradled between two mountains. Mane was picturesque, just below a hill, with fields on both sides and a crystal river flowing by its slopes.

Soon, dusk settled in, the moon was out and stars filled the sky. Dinner, a hot bowl of kew, was quiet and pleasant. On hearing dogs barking, Yarfel, my friend, whose house we took over, informed me casually that wolves may be close by. Surely, it couldnt be that easy I thought. “Jaldi," I said, as we ventured out of our huts. Under the faint light of the moon, I could make out some animal movement in the field below. I focused my LED Lenser torch and instantly spotted a canine-like quadruped move shyly away from the fields into the darkness. A wolf?

I looked around for spoor the next morning and found pugmarks on a definitive trail. But sheep dogs here were large too and I had to consider whether we were barking up the wrong tree. We decided to proceed to higher ground, where wolves might be denning.

Photo Courtesy: Salvador Lyngdoh.

Where wolves roam

We reached Dogsa, a seasonal pasture roughly 4,000 m. above Mane, situated on flat ground surrounded by rocky hill tops laden with Caragana versicolor, a keystone shrub. A dozen huts made from these same rocks served as summertime accommodation for locals, who spent most of their time making ghee (clarified butter) from milk and collecting dung cakes for fuel. The area was blessed with ample water and grass, so their domestic animals had plentiful sustenance. With luck, I knew, fossils could be found here on mountains that were once part of the Tethys sea. Most common among them are ammonites, a now-extinct group of marine molluscs. For geologists, Spiti in its entirety is a history book stratified with signs of prehistoric life including squid-like creatures called belemnites and huge, primitive centipedes that probably crawled about 500 to 600 million years ago. Treasures that speak of the history of our planet, these ancient relics are sold as cheap souvenirs and I wished visitors would at least pause to marvel at the miracles they held in their hands.

On a more positive note, I noticed several wolf tracks and scats along my two-hour hike up from the village.

Camping in wolf-land

We offloaded our contraptions and set up tents. Chai bubbled over the fireplace as villagers headed back with their cattle and sacks of firewood. Before dark, we set out traps on strategic key trails to maximise our chances of an encounter. The tried and tested traps were rubber-padded to avoid injury and prevent trauma from limb-freezing. Researchers trap animals to obtain blood samples and check on the health of subjects. We dug, embedded, camouflaged and anchored our traps; hoping wolves might be lured by the sound of cattle, sheep and goat. We tried not to leave our scent or traces of human presence as wolves are justifiably suspicious of Homo sapiens and even a hint of doubt would detract these cursorial predators.

As the night extended, pre-recorded howls were sounded to alert our wolves using a low-cost soundbox I acquired in Kaza. The young monk who sold the box had pointed out it was equipped with ‘bluetooth and could be remotely controlled.

We retreated to our tents, and prayed for good news.

Though the tents took a little getting used to, there is nothing like a good sleep under clear, star-studded skies. Very early the next morning, we awoke to the chatter of Himalayan Snowcocks. Some villagers said they saw bharal, or blue sheep, around the hill tops. I hurriedly grabbed my binoculars, when I heard a faint clanking sound. Climbing higher, the sound become more pronounced. Wolf! I whispered to myself, quickly waking the others.

Sure enough, there it was… a large, buff, healthy and exceedingly beautiful wolf. We moved a few metres closer to the animal and saw it was a female. Alarmed by our presence, she howled. Actually, it sounded more like a deep, long bark. Her paws were large and firm and she was big and strong. Her foot was firmly held by the rubber jaws of the leg-hold spring, enabling Sanath, our vet, to shoot a tranquillising dart that immobilised her within minutes.

Photo: Salvador Lyngdoh.

|

Until recently, wolves were the second-most widely distributed terrestrial animals in the world. Wolves evolved in Asia and radiated from Eurasia to North America around 500,000 years ago. Early ancestors of present-day wolves are dated back to the Miocene. The famous Dire wolves from Game of Thrones, if you watch the show, were the bigger relatives of the present-day grey wolf Canis lupus. They coexisted for about 100,000 years. Competition with Canis lupus, anthropogenic pressure and extinction of other large mammals till about 12,000 years wiped out the species.

Despite their large range, they have disappeared from nearly one-third of their former distribution. In the Indian Trans-Himalaya, it is estimated that roughly 350-400 adult wolves exist. The Himalayan wolf is known to be a unique and ancestral lineage of extant grey wolves; it has been argued that these wolves be placed as a separate species altogether. Worldwide, there are three species of wolves recognised currently, the grey wolf Canis lupus, the red wolf Canis rufus and the Ethiopian wolf Canis simensis. Recently, a revision through molecular phylogenetic studies suggests 13 subspecies of the grey wolf exist. Two geographically isolated populations and allopatric (meaning occurring in separate non-overlapping geographical areas) races exist in the Indian subcontinent. These wolves, due to their isolation, may have existed since ancient evolutionary times and which is why they may have played no role in domestication. Himalayan wolves thus may be a ‘Yeti of Sorts in evolutionary terms.

|

Studying the world's highest wolves

In the context of an animals use of an area, knowledge of its movement provides a ‘live point of contact between ecology and evolution. Thus, to even begin to understand why wolves move in space is to be able to answer why wolves use a resource at given times and extents. This helps protect a species in its chosen habitat. GPS-enabled radio collars have come a long way in helping researchers understand such movements, ranging from migrations to micro-movements. We chose to attach a ‘prefixed Globalstar satellite collar onto the neck of Kunzum - our she-wolf subject. The strength of a wolf is in its pack, and we hoped this wolf would reveal details of not only her life, but that of her associates as well.

The collaring operation was smooth and lasted just 15 minutes. Our beautiful Kunzum was about two or three years old and weighed about 35 kg. As the antidote did its work and began to wear off, she rose, staring balefully at us for a few seconds, before heading for the hills. Some distance away, she stopped momentarily, turned her head to look at us and then disappeared into the mountainous, cold, arid trans-Himalayan desert. She was only the second wolf to be collared in the Spiti Valley and the first to be tracked remotely in the Himalaya.

Mongolian wolves are the closest relatives of their Himalayan/Tibetan cousins. Recent genetic studies have even suggested that all these three races of wolves are of the same lineage. Studies from Mongolia suggested that one such female had a 20-month ‘resident period during which she inhabited an area of 1,275 sq. km., plus a nine-month ‘extension period where she enlarged its range to an astounding 6,634 sq. km. Our experience provided us an insight into the lives of ‘our wolves and we believe their range hovers around 2,000 sq. km., with the average daily range of a pack being about 20 km.

But, why track them at all?

If we want to protect them, we must know where they are, where they move to and why. In remote landscapes, wolf movements are a mix of complex factors including human pressures and a host of other environmental variables. Studies have shown that wolf occurrence depends largely on human pressure, prey availability, and landscape integrity. Simply put, wolves need habitat connectivity and access to food and water. In Spiti, our results have thus far revealed that wolves rely on domestic and wild prey such as bharal and ibex. Local attitudes, systems of life and tradition have allowed wolves to co-exist with humans for millennia. By tracking them we can understand wolf diet and this in turn can help reduce human-animal conflict.

Photo: Salvador Lyngdoh.

Is there a future for wolves?

Frankly, they are treading on thin ice. Feral dogs, disease and prey depletion could result in their complete extermination from the area we surveyed. Possible mating with feral dogs puts them at risk of genetic swamping. While the world cycles on, our lives are dedicated to the proposition that our meticulous observations of wolf behaviour and their relationship with humans and other wild species will one day help us to understand and protect the ecological landscape of Canis lupus. The significant events in the lives of wolves, their evolution and the manner in which they have adapted to the larger Himalayan system is interesting enough, but I believe our work could be critical to their survival when future conservation strategies are implemented.

Our day ended with joyous celebration and dances that village folk treated us to because they were just as thrilled as we were with our successful endeavour. A call placed to my colleague Dr. Bilal back at the Wildlife Institute of India (WII), located in far away Dehradun, confirmed our radio-collared wolf was on the move and was not too far away.

Interestingly, Spiti folks do not have an equivalent word for the wild. Maybe here, the original association with nature existed without such conceptual boundaries. The wolf may be a manifestation of such an association. It represents our deepest fear and our false triumph over nature. The wolf is a friend, not a foe. It would be difficult to imagine life without the greatest gift of the wolf to mankind i.e; the latters best friend. Living among the hardy people of Spiti, I realised that their cultural acceptance of the wolfs right to exist is the essence of its survival, as is its legendary resilience.

|

About the Study

The study is part of a team effort involving scientists and officers from the Wildlife Institute of India and the Himachal Pradesh Forest Department, including Dr. Bilal Habib, Dr. Y.V. Jhala and the author. Special thanks to Dr. P. Nigam, Dr. S.P. Goyal, Dr. S. Krishna, R. Sharma, DFO, D. Chauhan, RFO, Yarphel, Namgial Gompo, Namtak, Sushil, Kesang, Takpa, Nishi and all the people of Mane.

|