The Western Ghats Rhapsody In Black & White

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 21

No. 4,

April 2001

Text and photographs by Ian Lockwood

Rainmaker and biodiversity hotspot, the Western Ghats in peninsular India are among the country’s most important natural assets. Biologically rich, these mountain ranges are blessed with one of the highest rates of endemism in the subcontinent. Their cold heights intercept the monsoon clouds to ensure a continuous supply of water to the thirsting plains below. The Western Ghats stretch 1,440 km. from the Tapti River north of Mumbai to the tip of the Indian peninsula at Kanyakumari. Composed of a variety of ranges, they form a near-continuous wall separating the wet Malabar Coast from the drier regions of peninsular India.

Crucible of life

Conservation International defines biodiversity as the sum total of all life on Earth, the wealth of species, ecosystems, and ecological processes that makes our living planet what it is – a crucible of life.

Aside from the utter criminality of destroying what is not ours to destroy, from a purely anthropocentric point of view, biodiversity reserves hold the key to our future survival. Biodiversity also plays a key role in our daily existence in that all of our food is originally derived from wild plants and many of our medicines originated in the wild. A case in point is Kerala’s popular ayurvedic medical practice that uses medicinal plants found in plenty in the Western Ghats. The same goes for many modern drugs. In times of distress and disaster, when the species we depend on are hit by unexpected calamity, it will be such islands of biodiversity that will ensure our future survival.

The idea of a hotspot was first mooted by ecologist Norman Myers in 1988 who defined it as an area of exceptional plant, animal and microbe wealth that is under threat. There are 25 global biodiversity hotspots, ranging from the Brazilian Atlantic forest to Wallacea and the Western Ghats (which are sometimes grouped together with Sri Lanka). The other Indian hotspot is the rainforest-cloaked Eastern Himalayan region bordering Burma and China, which is also severely threatened.

Blessed with an abundance of life-forms found nowhere else on earth, Western Ghats endemics include the high-profile liontailed macaque Macaca silenus and the Nilgiri tahr Hermitragus hylocrius. Scientists working at the Wildlife Institute of India (WII), the Bombay Natural History Society (BNHS) and other notable organisations have been cataloguing endemics in the Western Ghats for several years. These experts estimate that there are 84 amphibians, 16 birds, seven mammals and a mind-boggling 1,600 flowering plants that are found here and nowhere else on earth. There are numerous lesser endemic life-forms and it is probable, that some of these have so far escaped documentation. For such a small area, this is an impressive list. The fact that these biologically rich areas are threatened by human activity places the area in the hotspot category.

The Ullam Pari Ridge, Tamil Nadu. The southwest monsoon can be seen over the distant hills of Kerala, which the plains of Tamil Nadu (foreground) remain exquisitely clear.

Rainmaker

Water, the life-blood of nature and human civilisation, is the strongest reason for protecting the Western Ghats. Every summer, ocean currents push the nourishing clouds of the southwest monsoon up the Malabar Coast. The Ghats prevent the monsoon clouds from reaching the interiors of the peninsula. The hill tops force most of this rain to fall on the western coast and mountains, and by the time the clouds reach the peninsula’s interiors, they have lost their precious cargo. The forested slopes of the Western Ghats, like a giant sponge, absorb the rainwater, releasing it to the thirsty plains below during the ensuing drier seasons. The Kaveri and Krishna are only two of the eastward flowing rivers fed by the Western Ghats.

When natural vegetation – forests and grasslands – are destroyed and replaced by plantations and other human interventions, the mountains yield less water to the plains. Protecting the Western Ghats and its natural vegetation is thus vital to the millions of people living in its watershed areas on both the eastern and western sides.

The Upper Falls, Kutrallam, Tamil Nadu and this stream in the Kalakad-Mundanthurai Tiger Reserve highlight the vital role played by the Western Ghats in supplying water to the plains. But these ranges have a value that exceeds the physical – they provide nourishment for the soul.

Food for the soul

An amazing variety of mountain and forest habitats provide a breath of fresh air for those seeking to reconnect with nature in the Western Ghats. At Kanyakumari, the mountains rise abruptly from the plains and sea. In the wetter zones from Kerala to Maharashtra, fabulous rainforests teem with birdsong and the buzz of insects. Above these forests, protected by high cliffs, are plateaux whose biotic composition is influenced by cooler temperatures and high-velocity winds. The unique grasslands-shola ecosystem dominates the higher plateaux that have escaped development. Dry, deciduous forests still carpet many of the slopes on the eastern face of the Ghats.

From Karnataka northwards, the Ghats meet the expansive Deccan plateau. Compared to the hills south of the Nilgiris (on the Tamil Nadu, Kerala and Karnataka border), these hills have lower elevations. Composed of ancient lava flows, they fall in steep, dramatic ghats (steps) to the sea along the Konkan coast north of Goa (recently confirmed as tiger habitat). Amidst the increasing urbanisation and signs of human presence, the Western Ghats have a value that exceeds the physical – they provide nourishment for the soul.

The Upper Falls, Kutrallam, Tamil Nadu and this stream in the Kalakad-Mundanthurai Tiger Reserve highlight the vital role played by the Western Ghats in supplying water to the plains. But these ranges have a value that exceeds the physical – they provide nourishment for the soul.

Past and future

The Western Ghats have been protected from serious exploitation throughout much of India’s long history. Sheer inaccessibility has made the mountain terrain difficult to cultivate and settle on. The indigenous communities that overcame these challenges learned to live with the habitat, not against it. Their ecological footprint was small. Many of these people still exist, like the Mudhuvan tribals of the High Range, but their ways of life are as endangered as their mountain habitat.

The isolation of the Western Ghats changed during the British period when large areas of virgin tropical forest were cleared for tea, coffee and spice gardens. These changes have continued today, as evidenced by the cutting of the Konkan railway alignment. As in other parts of India, the Western Ghats too are threatened by development projects, habitat loss and poaching.

The Naraikadu forest, Tamil Nadu is private property, but forms part of the Kalakad-Mundanthurai Tiger Reserve and is therefore zealously guarded from timber merchants and poachers.

Perhaps the least-noticed intrusion in the 20th century has been the replacement of the natural vegetation of the Western Ghats on a massive scale with exotic tree species. There are few areas that are free of these lethal monoculture plantations. Most visitors mistake eucalyptus, pine and wattle trees for a part of the natural hill-station landscape, when they are in fact dangerous invaders. Mega hydroelectric and irrigation schemes with dubious long-term benefits have also been pursued vigorously in the last 50 years, submerging and fragmenting extensive forest areas. It took the hard-fought Silent Valley campaign in Kerala to awaken people to the negative impact of our unquestioned dam building spree. But today, even this fabled valley has been invaded.

Habitat continues to be lost to expanding hill-station development and the demand for minerals. Hill-stations are becoming the antithesis of the quiet rejuvenating experiences that they were designed to be. Towns like Ooty, Kodaikanal and Mahabaleshwar used to be places of peace and reinvigoration. They are now overwhelmed far beyond their carrying capacity by motorised, trash-throwing hordes. In the Nilgiri hills, one of the first ranges of the Western Ghats to be developed as a hill-station, film-makers recklessly shoot in sensitive habitat, leaving a trail of dirt and degradation. Worse still, viewers often seek to imitate the exploits of filmstars in these same locations. Meanwhile, mining in and around several protected areas is an ongoing challenge to the sanctity of the mountain range.

Much has been done to protect this ecologically fragile area and the sweat of previous generations has ensured the survival of well-known sanctuaries such as Periyar, Nagarahole and Silent Valley. Courageous individuals, both in and out of government, have dedicated their lives to protecting this unique part of India. Despite this, experts estimate that of the 159,000 sq. km. area of the Western Ghats, only 8.1 per cent is protected. Today, it is critically important therefore, to continue spreading the message of conservation in the Western Ghats, especially to city dwellers who have a vital role to play in its protection. Wasteful consumption of resources puts pressure on the fragile habitats from where most of this wealth originates.

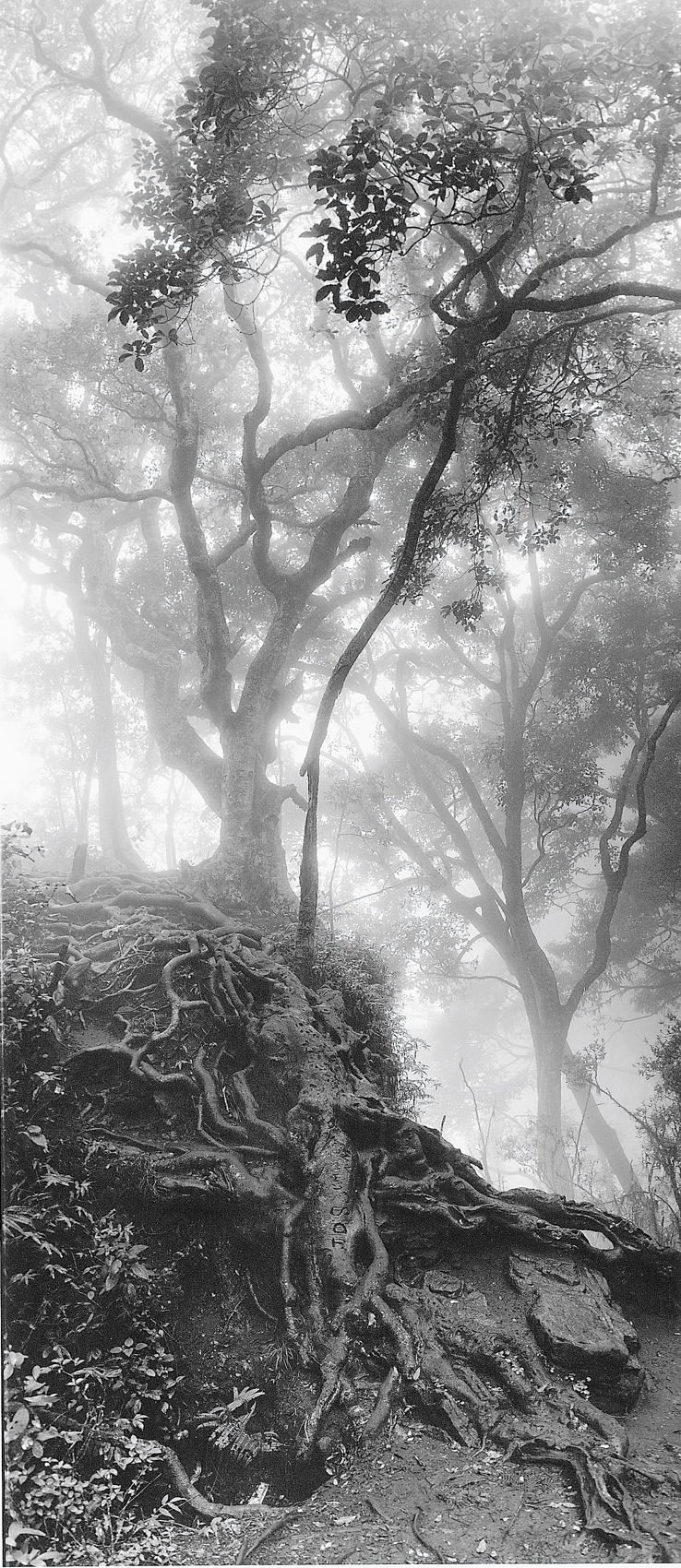

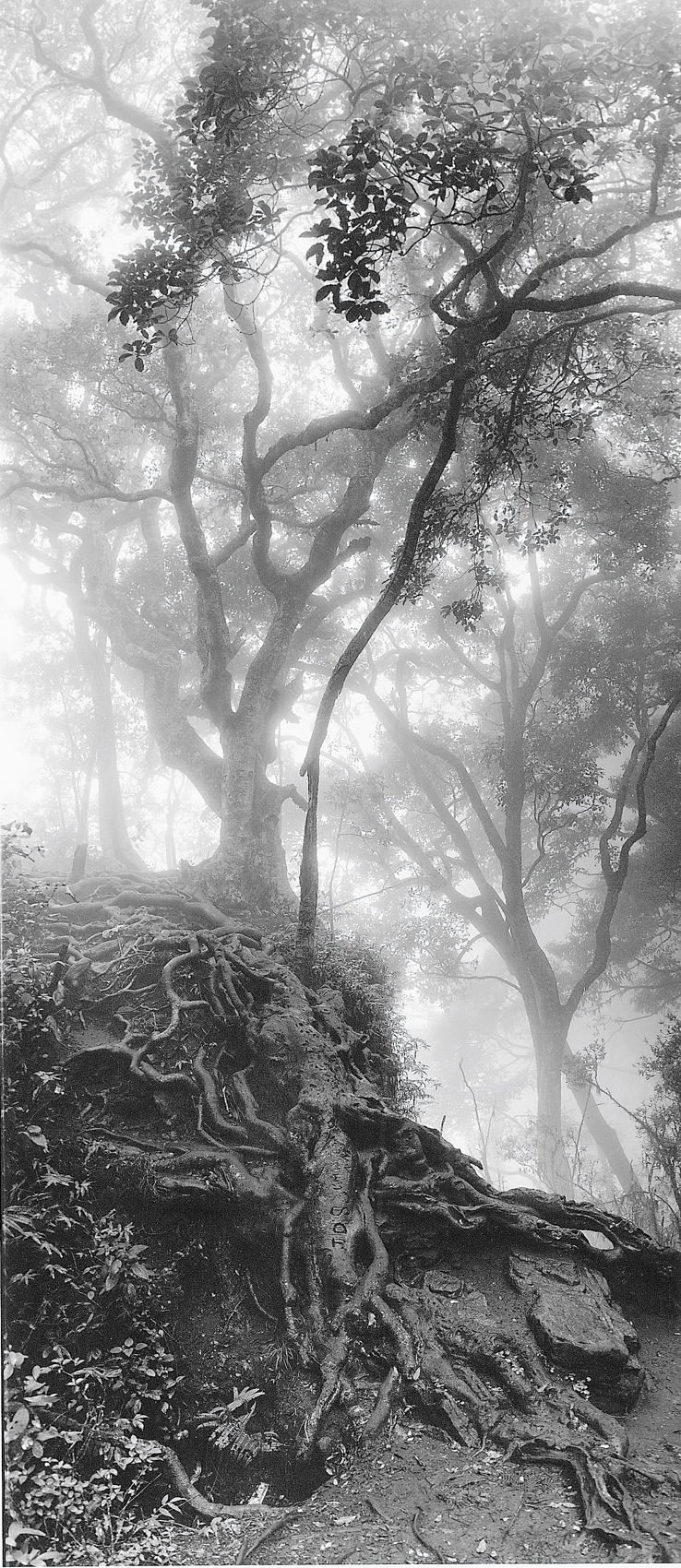

The Devil’s Kitchen Shola at Palni Hills, Tamil Nadu is part of the unique high-altitude Western Ghats ecosystem.

Those of us who have been touched by the magic of the Western Ghats await a new appreciation of the phenomenal importance of these mountains and public recognition of the value of conserving them. And there is a clear need for a new edict of environmentally responsible behaviour in hill stations - one that stresses on walking over motorised transport, cloth over plastic, quiet over noise and natural over the exotic.