Tourists from the Dark Side

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 35

No. 10,

October 2015

By Shailendra Yashwant

In the lush Periyar landscape, journalist Shailendra Yashwant weighs the pros and cons of wildlife tourism as he confronts the wrong edge of the tourism sword, sharpened by ignorance, greed and the in-built limitations of Forest Departments across India.

August 15, 2015, Periyar Tiger Reserve, Kerala: The elephant turned his head around as soon as the mobile phone rang. Incredulously, the young man ignored the loud caller tune and continued taking pictures of the glaring pachyderm. His wife also turned her attention and phone towards the elephant to nonchalantly shoot a quick succession of pictures using her camera flash. The driver started the jeep and could be heard cursing the couple as he reversed and swiftly drove away.

Ajayan, the upset jeep driver, told me later that he had informed the young honeymooning couple very clearly before the trip that “they are not allowed to use camera flash, that phones must be on silent, they should not wear bright colours and if they did not follow rules I could not guarantee their safety. But the two of them were ‘hopeless’ and broke every rule. I had to leave in a hurry not because the elephant had shown any signs of discomfort or displeasure, but because I know even elephants have limits to their patience.”

On January 20, 2015, not very far from here, allegedly provoked by a camera flash, an elephant lost his patience and killed Bhupendra (52) and Jagriti Ravel (50) in the Gavi forest of the Periyar Tiger Reserve. The forest guide accompanying them was forced to abandon the couple after they failed to heed his warning to stop taking pictures and run. This is not an isolated incident but typical of the rising animal-tourist conflict unfolding in our parks.

S. Balaji, a businessman from Coimbatore and a regular visitor to the Periyar Tiger Reserve for the last two decades doesn’t understand the camera-wielding Indian tourist. “How can they tell how much fun they had in the forest on the basis of the photos they take? How can they enjoy the beauty of nature if they are only looking through a camera’s viewfinder? It is not as if they all take great pictures. I come to this forest to record its beauty in my mind and in my heart so I can always remember it. But now the forest is full of jerks and hooligans with cameras and not an iota of forest manners,” he says.

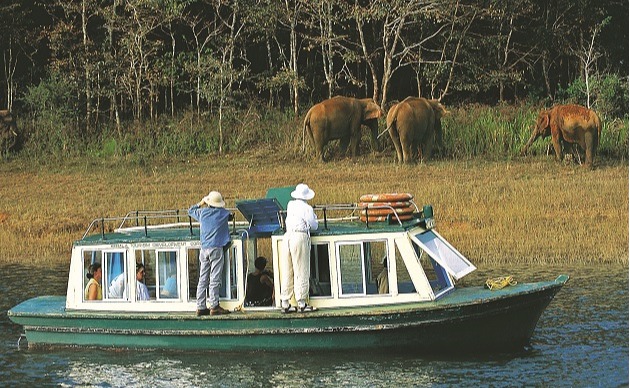

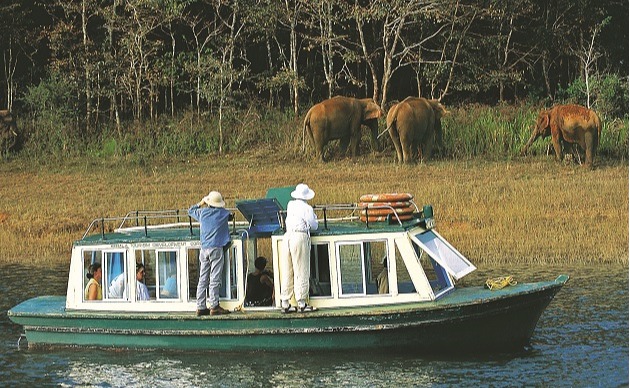

Enthralled tourists on a boat safari on the Periyar lake observe wild elephants. Photo Courtesy: Dr. Anish Andheria

The Big Fat Indian Tourist

It’s Independence day; we are sitting on the banks of the Periyar lake and watching tourists being ferried in boats. Usually the vessel is filled with noisy holiday makers. But today the groups distributed in five boats are silent and awestruck. The forests on the banks of the Mulaperiyar dam reservoir are stunning. There are no elephants, but two herds of chital, a few sambar, a lone wild pig and three gaurs have already been spotted, enough to keep the Independence day holiday crowd engaged and happy.

With or without the cameras, Indian visitors are flocking to national parks in unprecedented numbers. A big-mammal sighting is a must for these modern wildlife tourists. Tiger sightings are the biggest draw in Corbett, Ranthambore, Kanha and Tadoba. However, in the popular national parks of south India – Mudumalai, Bandipur and Periyar, elephants and bisons are the big ticket subjects, while in Kaziranga, it’s a rhino. They are coming in hordes from everywhere, with money to spend and experiences to collect. Treks, night camps, leech-infested jungle trails, jeep safaris, elephant safaris, boat rides, tree houses... everything gets booked and quickly. There is no longer an ‘off-season’ for national parks unless they are mandatorily shut down during the monsoon.

Forest etiquette demands that wild animals be respected and given space by tourists. Here, an elephant is given the right of way in Kaziranga National Park. Photo Courtesy: Ashish Parmar

When not satisfied with sightings on Forest Department tours, many of the tourists are willing to hire the expensive services of unscrupulous tour operators who promise close encounters of the risky and illegal kind. This includes private and personalised tours to core areas of forests and marine parks officially closed to tourists, night safaris that are banned and, during my last visit to Bandipur, even an exclusive dinner with a tiger feeding on its kill – “Sir, tonight is the night, we know where to go, the Forest Department will never come in time sir, nothing to worry. Only you, exclusive shots, your camera deserves it sir, don’t miss!” was the canvassing pitch.

“No wonder then, the elephants are hitting back. Surely so will the tigers, the lions, the bears and the bison... irrespective of the number of likes you get on your Facebook page,” rue the more serious wildlife enthusiasts and photographers.

The tourist-animal conflict is only one small facet of the problem around our parks, there is simmering conflict within local communities, external tourism operators and the authorities, over the profits from the tourism boom. Greed, not conservation, seems to drive the vessel in wildlife tourism.

Is tourism not the answer?

Given the Forest Department’s limited capacity, limited experience in hospitality and tourism, and the new restrictions on building or expanding facilities inside Protected Areas, privately owned lodges have mushroomed. This has given rise to unplanned growth, unorganised, unlicensed and untrained tourism operators and even some shady businesses on the fringes of Protected Areas. This has the potential to ruin the destination, and cause more damage than good thus defeating the very objective of wildlife tourism - to protect and preserve with public participation.

Big cat sightings such as this are undoubtedly great to come by, but tourists often resort to underhanded ways to be assured of one. Photo Courtesy: Sharookh Mehta

A recent report by the Wildlife Institute of India (WII) – Wildlife-tourism, local communities and tiger conservation: A village-level study in Corbett Tiger Reserve examines how tourism has affected Dhikuli village, a cluster of some 200 households with about 1,600 people, just outside the eastern edge of the Corbett National Park in Uttarakhand. The study has established that wildlife tourism is disrupting the social fabric of local villages, creating pockets of prosperity, while injecting new tensions by driving financial disparity, resentment and conflicts within village communities on the edges of the reserve. The Corbett study also found that the influx of tourists has exacerbated the pressure on villagers for water. One villager told the WII researchers that while water was available relatively easily before the growth of tourism, much of the water is now consumed by tourist resorts near the reserve, leaving villagers with less than they need.

This resentment and the fight over tourism profits manifests itself in various forms in different Protected Areas. In Periyar, a small section of tourism agents, auto and taxi drivers from the adjoining town of Kumily have declared a virtual war over the management’s efforts to streamline activities in the tourism zone as per the Ministry of Environment, Forests and Climate Change’s (MOEFCC) recent guidelines. Billboards accusing the management of colluding with private operators, and lack of transparency have been put up by the protesters at the entrance to the park where they hold regular demonstrations.

Engaging locals, the true stakeholders of the forests, as guides, protectors and coordinators is crucial and beneficial to sustainable tourism. Photo Courtesy: Dr. Anish Andheria

Solutions exist and can be implemented

In spite of the fact that millions of pilgrims visit the Sabarimala shrine for a period of 60 days every year, the 975 sq. km. Periyar Tiger Reserve is fortunate in that its tourism development is limited to a single cluster at the park entrance in Thekkady, which impacts less than two per cent of the park. The transformation of this village into a full-blown tourist town in less than a decade has surprised even the locals. The homestays, hotels and resorts are constantly expanding and adding rooms without considering the carrying capacity of their fragile environment. Most of these resorts lack proper sewage and garbage disposal systems. Raw sewage from toilets is let into the nearest stream or nullah that flows into the park and downwards to Tamil Nadu.

In peak season there is a long line of vehicles waiting to get in from the Thekkady entrance, causing jams that back up all the way to the Kumily bus stand. Unfortunately, the small section of disgruntled tourism operators have managed to stall construction of a much-needed car park and sewage treatment system, ironically through the National Green Tribunal, which otherwise is a champion for wildlife. All this is despite the fact that the Periyar Tiger Conservation Foundation that is in charge of all tourism and related community development projects in the tiger reserve is recognised globally for its pioneering initiatives to include local communities in economic and ecological activities (See Interview with Sanjayan Kumar, Deputy Director, Periyar Tiger Reserve).

At Periyar, the Forest Department has consistently made efforts to work closely with local communities. Like so many other tiger reserves, communities here have sacrificed their ancestral forest rights and concessions, and have been relocated outside the national park. To watch the Protected Area gain international acclaim and play second fiddle to a tourism industry largely run by wealthy outsiders has resulted in communities feeling disenfranchised and resentful.

The community tensions triggered by the tourism boom are palpable in nearly every park. Even when the impact of garbage and sewage on the habitat is clearly visible, there are few studies available on how this impacts the flora and fauna.

Every year between mid-November and mid-January, millions of devotees visit the Sabarimala temple exerting immense pressure on forest resources. Photo Courtesy: Dr. Anish Andheria

Having said this, the surge in wildlife tourism could and should convert into much needed finance for conservation, and community development. But tourism providers will themselves need to come up with high-quality visitor experiences, in line with market expectations, that are commercially viable.

Unfortunately, as of now, in the absence of any formal training and access to finance, local communities are at the bottom of the profit sharing pyramid and are usually employed as drivers, guides or menial workers. This breeds even more resentment and leads to conflicts of the type we see unfolding in Periyar.

“First we must provide tourism education for all the local people, which means we must sensitise all villagers, right from school students to village elders about how they all are stakeholders in this business, then we must provide training to local youth to engage them in the tourism business, at least one person from every local household should benefit from the profits of tourism but on one condition – that each family in turn commits itself to be a protector and ambassador of the forest,” says Thampan Varkey, a spice farmer who runs a tourism boutique shop in Thekkady.

“Mandatory orientation and introduction to forest rules and regulations is a must for every visitor to the park, this is one way of ensuring that they behave themselves in the forest and in the presence of wild animals, and hopefully this will also bring an end to the practice of a few unscrupulous operators who lure tourists for illegal sightings.” says S. Shridhar, a businessman from Chennai who spends his vacations visiting national parks around the country.

Clearly, wildlife tourism can only be sustainable if it contributes to the conservation and survival of wildlife and their habitats, offers local communities better living conditions, educational and livelihood options and entices the visitor with good quality tourism amenities.

But for this to happen, we will have to redefine wildlife tourism to expand its scope beyond the current model that is based mainly on sightings of iconic species. What is needed is a more holistic experience for the visitors, where they will learn about the natural history of the forest, the culture and tradition of the local communities and the importance of the wildlife conservation and environmental movements. Only then we can hope to achieve the main aim of wildlife tourism - to convert every visitor into a guardian of our natural world.

INTERVIEW WITH SANJAYAN KUMAR,

Deputy Director, Periyar Tiger Reserve (East division)

Photo Courtesy: Shailendra Yashwant

With over 8,00,000 visitors, how can you retain Periyar’s status as one of India’s best preserved protected areas in community-based ecotourism practices?

The issues facing the Periyar Tiger Reserve are the same as those faced by other Protected Areas in India. Compared to parks in Africa and other forests abroad, the size of our forests are very small and they are under tremendous human pressure in the form of poaching, smuggling, fishing, firewood collection and other biotic pressures. Periyar too faced these issues not very long ago, we had hardcore poachers operating here. In fact, at one time the male-female ratio of elephants in Periyar had dropped to 1:50 due to selective poaching of tuskers. Smuggling of Canarium strictum (black dammar), cinnamon bark and other non-timber forest produce was widespread. To add to all this, we have up to two crore pilgrims visiting the Sabarimala shrine inside the forest for a period of 60 days every year.

The process of dealing with these issues started in the mid-90s through the India-Eco-Development Project (IEDP) and each problem was dealt with in a systematic manner. At first we organised local communities into Eco-Development Committees (EDCs) based on the identified issues and challenges.

Today, there are four types of EDCs in Periyar –

1. Professional group EDCs that offer alternative employment to former poachers and smugglers. The cinnamon bark smugglers now work as guides on tiger trails, the Tamil poachers take tourists bamboo rafting, Theni poachers are now part of protection watch and others who have been employed in tourism-related functions come under this programme.

2. User group EDCs provide innovative income generation alternatives to those who were directly dependent on the forest for fishing, honey and firewood collection. For example, the villagers who used to collect firewood for income are now collecting long grass that they sell to resorts.

3. Neighbourhood EDCs are villages on the fringes that are not directly dependent on the forest, but if not involved, can damage the park by throwing garbage and harbouring poachers. Their involvement in conservation is essential and they are provided with market assistance. For instance, we help sell their organic pepper to German markets where they earn almost 30 per cent more than in auctions at Kumily.

4. A very specialised group of EDCs for pilgrimage management, which ensures everything from a garbage-free pilgrim route, provision of drinking water and cooking fuel to reduce pressure on the forests during the 60 days of pilgrimage.

We have succeeded due to the concerted efforts of the department, and commitment of the local communities, combined with a genuine participatory approach that looked at the challenges from the prism of economic, sociological, and sustainability indexes. All the solutions were implemented in a transparent manner.

There are some tourism operators that are unhappy and protesting against the park authorities…

The current protests are against our efforts to streamline advance online booking systems for different park activities. This has been a long time demand of tourists to be able to book tickets before arrival to avoid disappointment as the boat tours are very popular and fill up fast. This new system has impacted a few local miscreants who book tickets in advance to sell in the black market later, a menace that needed to be checked. I understand that local agencies which offer these tours also need to survive. We have even offered to find solutions like reserving 50 per cent of the tickets to be sold by local tourism operators. We also offer them promotional fees, not for block bookings, but for individual registered tourists. But this is not acceptable to some of them. Despite your best efforts there will always be a small number of miscreants for whom it is all about money.

Are there any studies or observations of change in animal behaviour due to exposure to tourists in Periyar?

Tourism in Periyar is only restricted to a small periphery of the park where density of animals is very low. In any case our most popular attraction - the boat tour in Periyar lake, unless full of unruly and noisy picnickers, has very low impact on the park. Our forest treks and trails are designed for serious wildlife and nature enthusiasts who are always accompanied by trained staff and a guard. Proper briefings and safety instructions are provided in advance. The walking distance and hardships on the trail act as filters for casual tourists. The only known change in behaviour is amongst the macaque population of the park. Unfortunately, tourists feed them, even though we strictly prohibit such behaviour through warning signs. We are improving our waste disposal system and also warning systems for the visitors. But 100 per cent control of tourist behaviour can only happen if we transport them in our vehicles in and out of the park and that is what the parking project will achieve.

What is the future of wildlife tourism? What can be done to improve visitors’ experience to achieve the forgotten but most important driver of ecotourism, That is education and environmental awareness?

There is a huge scope for improving the quality of experience for visitors to national parks. For example, we lack high quality natural history exhibits in India. Each park can have a good museum that is able to give detailed information and an educative experience about the natural history of the forest, its habitat, species and local communities. I turn back almost four-five lakh visitors every year from our gates because the main attraction, the boating experience, is full. If we had a good quality museum depicting the natural history of the Western Ghats, they would definitely not go away disappointed. We can also introduce good quality audio-guides that provide information about the park. This will also improve the quality of the boat ride and in future, the battery operated buses from the central parking outside the park. It is important that every tourist becomes a future custodian of our forests, for which we have to inform, educate, entertain and offer them the right experience in our national parks.

The last selfie

January 2015: Bhupendra B. Ravel, 52, and Jagriti Ravel, 50, were killed by an elephant when they tried to take a photo while on a trek in the Gavi forest near the Sabarimala temple, at Periyar.

October 2014: Deepali Rinkesh, 34, a tourist from Gujarat, was trampled to death by a tame elephant at Munnar in full view of her husband and son. She was trying to take a selfie with the elephant after riding on it.

September 2013: Colin Manvell, 67, a British tourist, was trampled to death by an elephant while taking a photograph near Tamil Nadu’s Masinagudi forest. The elephants in all cases reacted to a photograph being taken… either the flash or the sound of the shutter, or by rowdy tourists unaware of the rules of the forests.

Rule 1: Better safe than sorry. Always. Make sure you have a forest guard or official guide. Give the cheaper, unlicensed guides a miss, irrespective of their claims about how well they know the forest.

Rule 2: Familiarise yourself with the terrain and carry a compass and map if you can. Inform officials of the exact route you intend to take. Vehicles can fail. Feet can give in. Crossable streams can become unnavigable with just an hour’s rain.

Rule 3: Be aware of what’s going on right next to you. At all times. Before losing yourself behind the viewfinder, make sure that tiger, or elephant, or rhino do not somehow feel threatened, or blocked.

Rule 4: Be respectful. You are a guest of nature and are expected to behave. Avoid the flash. If your camera permits, use the quiet shutter mode, or damp the sound by covering the camera in a cloth.

Rule 5: Be sensible. Virtually every animal can outrun you. And those that cannot may be able to bite you. For heaven’s sake don’t try to get too close, or it might just be the last frame you ever shoot. Even a gentle ‘tap’ of an elephant trunk or the ‘caress’ of a tiger’s paw could put paid to all you dreamed you wanted to be.

Rule 6: Look again at Rule 4. Be respectful. Of animals. Of their homes. Of the weather. Of the authorities. You are out of your element and are NOT in charge.