Wildlife Conservation Society

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 36

No. 2,

February 2016

By Prerna Singh Bindra

From a schoolboy keen on birdwatching to an engineer, a farmer and finally one of the world’s leading tiger biologists – the arc of Ullas Karanth’s personal journey is fascinating in itself, but becomes even more significant when you consider how closely it is linked to the evolution of the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) in India. The WCS programme has evolved from a single predator research project in one national park in 1988 to a ‘conservation umbrella’ now supporting over 100 passionate wildlife conservationists, who share the same vision of saving wildlife and wildlands. WCS is engaged today in cutting-edge research as well as active conservation not only in the Western Ghats where it all began, but also in many other key wildlife landscapes across India. As WCS completes three decades in India, Sanctuary Asia asked conservationist and writer Prerna Singh Bindra to visit the WCS field camp to meet Dr. Karanth and learn more about the work being done.

“There was almost no wildlife left in the Malenad forests. Forget tigers, seeing even a chital, now found aplenty throughout Nagarahole, was rare. Gunshots echoed through the night, hunting was rampant, squatters encroached and cleared the jungle to grow paddy, and loggers felled trees. As a college student wandering this chaotic landscape, I did not think I could ever see my favourite animal, the tiger, in those forests.”

That’s how Ullas Karanth, Director for Science Asia, Wildlife Conservation Society (henceforth WCS or ‘the Society’), looks back on his visits to the forests of Malenad in the Western Ghats of Karnataka in the 1960s. Fifty years later, Karanth has a different story to tell. The same landscape is now home to the largest contiguous wild tiger population in the world, attaining ‘saturation densities’ of 10-15 tigers per 100 square kilometres in hotspots such as Nagarahole, Bandipur and Wayanad, in the Western Ghats.

As with many wildlife areas in India, Nagarahole’s story has been reshaped mainly due to strict wildlife laws and their tough implementation by forest staff in wildlife reserves after the early 1970s. In Nagarahole, however, there was another protagonist: Ullas Karanth, who first came here in 1967, and initiated his tiger research two decades later.

The seeds of Karanth’s interest in wildlife were sown in childhood by his father, and an aunt who gifted him a well-thumbed copy of Dr. Sálim Ali’s The Book of Indian Birds. But it was the legendary George Schaller who pioneered the scientific study of tigers at Kanha in Central India in 1963 that most influenced Karanth. Reading about his work in Life magazine, Karanth knew this had to be his life’s work. However, ‘wildlife biology’ as a profession was then unheard of in Puttur, the village near Mangaluru, Karnataka, where Karanth grew up. So he chose the traditional career path of studying engineering to ensure job security. His first factory job kept him cooped up and it felt “not unlike a concentration camp”. So he switched to selling tractors, which allowed him to bike across Malenad, his trips usually ending in nearby forests. He later took to farming “to be near Nagarahole”, and was more or less resigned to being an amateur naturalist. Then an opportunistic meeting in 1983, with Mel Sunquist, a pioneer of tiger studies in Chitwan, Nepal, and scientists of the Smithsonian Institution, changed the course of his life. Karanth became a student again at 35, at the University of Florida, under the tutelage of Sunquist. Karanth was also inspired by naturalists such as E. P. Gee and M. Krishnan, and along his journey was mentored by extraordinary foresters like S. Shyam Sunder and K. M. Chinnappa. He even went camping in the Nilgiris with the hunter-naturalist Kenneth Anderson!

The Secret Life of Tigers

In 1988 came another significant milestone. George Schaller handpicked Karanth, who was by now a qualified wildlife biologist, to start the Wildlife Conservation Society’s India programme. Karanth began his path-breaking tiger research in Nagarahole, a project that nearly three decades later, is the longest-running tiger research project in the world.

Karanth’s research and conservation work on tigers, leopards, dholes and prey species now covers over 30,000 sq. km. of the Malenad Tiger Landscape (MTL), encompassing several nature reserves in the Western Ghats of Karnataka, Goa, Kerala and Tamil Nadu, a global biodiversity hotspot harbouring over 450 wild tigers, 4,000 elephants and other endangered wildlife.

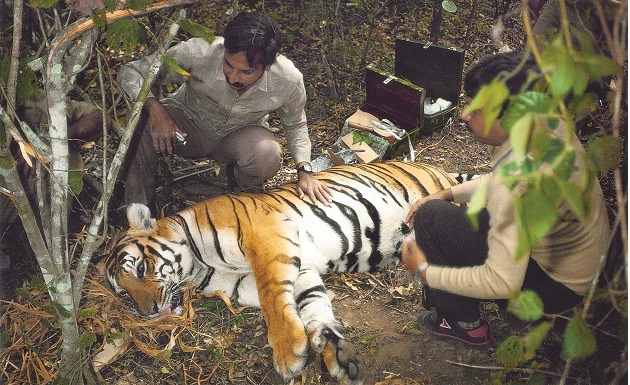

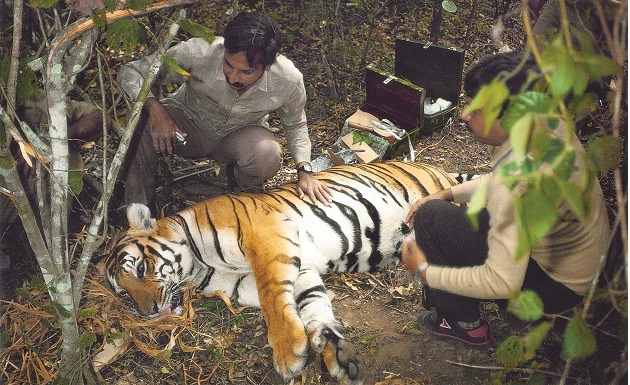

Karanth’s radio telemetry study of tigers in 1989, the first such in India, yielded valuable information about the secret life of tigers. How much space do they need? When do they breed? What affects tiger reproduction? His subsequent research established that more prey meant more tigers and greater reproduction, and, the key to tiger survival was a sufficient prey base. The insight that protecting tigers from commercial poachers wasn’t enough when hunting for the pot by locals was depressing prey populations, came as a breakthrough in global tiger recovery strategy.

A young Dr. Karanth, who introduced radio telemetry to study tigers in 1989. The strategy yielded hitherto unknown facts about the secret life of tigers. Photo Courtesy: Fiona Sunquist.

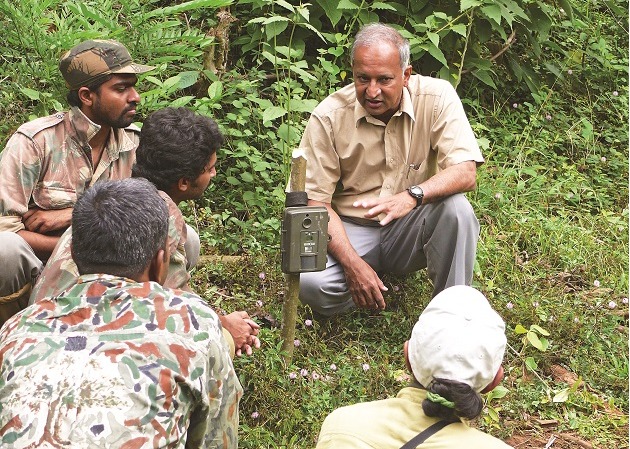

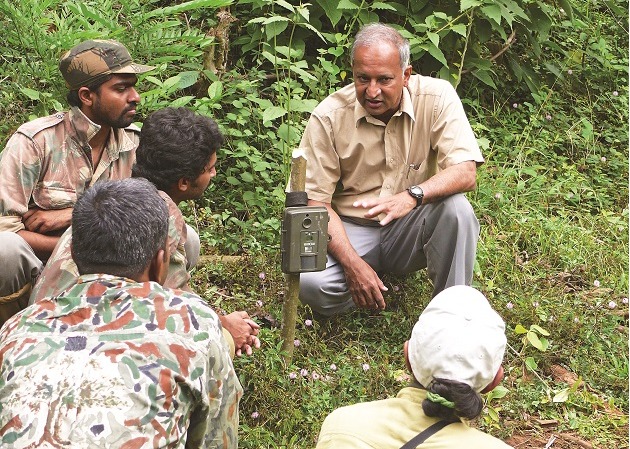

For the onerous task of estimating prey densities, Karanth applied a method called ‘line transect sampling’ for the first time in India. He trained local naturalists to walk the ‘transects’ (paths placed systematically across a landscape) to count prey animals with scientific rigour. This initiative has evolved into an extraordinary Citizen Science programme, birthing cadres of conservationists committed to protecting wildlife across Malenad, and, increasingly, across the country.

The Age of Selfies

The 1990s brought a new tiger crisis to India. While the country was congratulating itself for having doubled tiger numbers to nearly 4,000 since Project Tiger began in 1973, seizures of large stocks of tiger body parts began to peel away the facade. The uncovering of the massive illegal trade in tiger parts raised uncomfortable questions: if poaching was taking such a huge toll, were tiger populations actually as healthy as the government claimed? How many tigers did India really have?

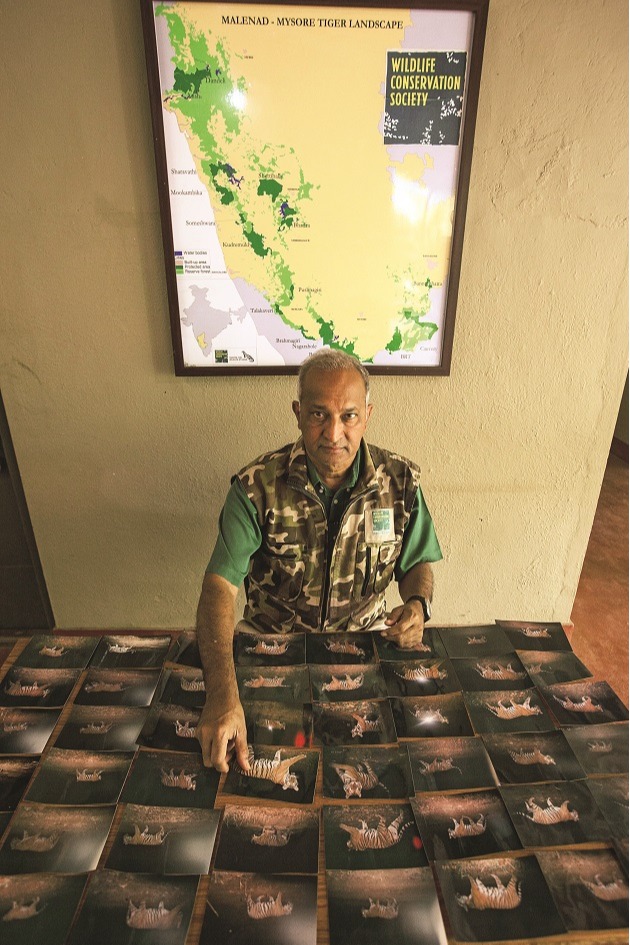

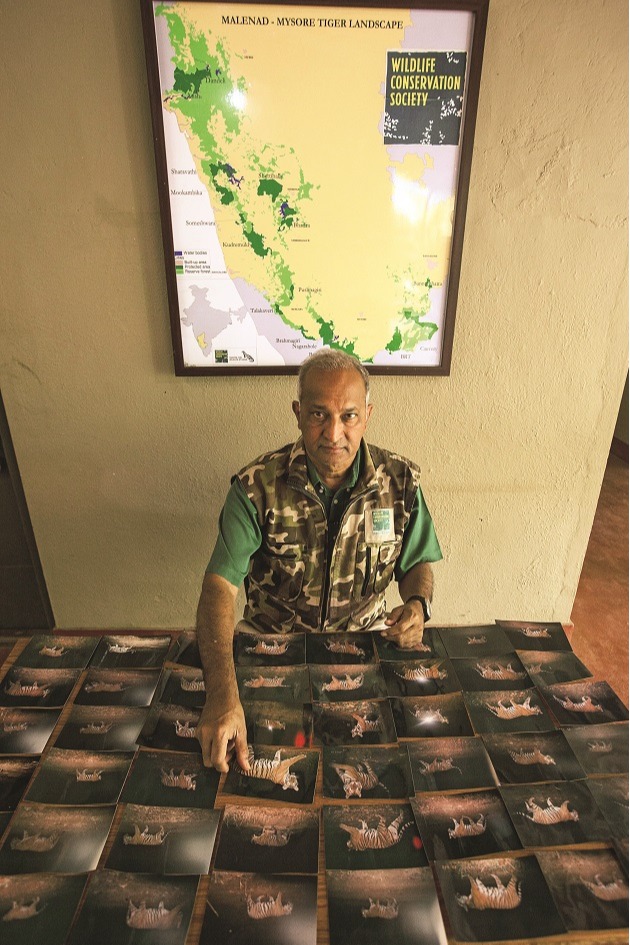

Karanth questioned the inefficacy of the official pugmark-based tiger census, and advocated a more reliable method that he had developed. “I began ‘photo-trapping’ tigers using automated cameras triggered by the animal as it passed by,” says Karanth. “Because each tiger’s stripe pattern is uniquely identifiable, I was able to count them accurately using the photos, which pugmarks had failed to do. These tiger counts were meshed with sophisticated statistical models to reliably estimate tiger numbers,” he explains.

It took over 20 years — and the Sariska tiger extinction debacle — for India to be rid of the outdated pugmark census. The government eventually adopted Karanth’s photographic capture-recapture sampling method using automated camera traps to estimate tiger numbers in reserves.

This invisible eye on tigers and other wildlife has grown from just providing tiger numbers, to yielding incredible information on population densities and trends, mortality and survival rates and even documenting long-distance dispersal of sub-adults. One such ’selfie’ of a tiger BPT-241 in Bandipur showed that this young male dispersed nearly 300 km. to Shimoga district, where it ended up being captured as a ‘problem tiger’.

Dr. Karanth examines camera-trap photos of tigers from the WCS database. Photo Courtesy: Sandesh Kadur

The camera traps have proved useful for crime detection as well, helping authorities to identify individual tigers from skins they seized from poachers. For instance, a skin seized by Nagarahole officials in January 2008 was identified as NHT-196, a tiger whose camera trap photos were in the WCS database since March 2004, helping in the poacher’s prosecution.

Karanth strongly believes that conservation must always be underpinned by sound science. He says, “As in technology, or medicine, science must play a major role in guiding conservation, letting us know in real time whether we are on the right track. If we are to save tigers, we need to study their ecology. While it is really our passion that goads us into conservation action, unless backed by reason and science, such actions may fail to deliver. Unguided passion can even cause harm to conservation such as how the attempts to release ‘man-eating tigers into new homes’ more often than not leads to fatal consequences for both people and the cats.”

Head, Heart and Guts

It is this pragmatic, focused approach to conservation, married with passion – a sort of ‘head and heart’ approach – that sets Karanth and, hence WCS, apart. But the Society’s hallmark has also been its uncompromising commitment to wildlife and wild lands, which has withstood even the most vicious backlash.

When advocacy groups guided by Karanth sought to halt the operations of the mining giant Kudremukh Iron Ore Company , it took them a bitter six-year legal battle before the Supreme Court shut down the mine. In retaliation, Karanth and 18 associates – including Niren Jain, then a young and idealistic volunteer – were defamed, intimidated and harassed through multiple cases of criminal trespass. It took another splenetic eight-year battle in the High Court of Karnataka before these cases were dismissed as clearly being of malafide intent. Karanth recalls with gratitude the staunch support from conservationists Praveen Bhargav, Valmik Thapar and senior advocate Udaya Holla in that long, tough battle.

WCS’ work now encompasses several Protected Areas in Goa, Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Kerala and Karnataka, where this leopard was camera trapped at Nagarahole. Photo Courtesy: Ullas Karanth, WCS.

Karanth’s WCS team and conservation partners fight relentlessly to safeguard their tiger turf. They have successfully halted night traffic on highways through Bandipur and Nagarahole, fought several poorly-planned projects for micro-hydel and wind power, and, luxury resorts across the Malenad landscape. They also work closely with dedicated local forest officials to tackle wildlife crime. In addition, they have lobbied governments to bring in additional areas under the Protected Area network.

Another significant contribution has been the Society’s early recognition — in the 1990s — of the need for conservation NGOs to unequivocally support voluntary relocation of people from core wildlife habitats. This is acknowledged to be a major contributing factor to India’s conservation successes today.

Though tiger conservation remains at the core of WCS-India’s work, its canvas has now expanded to include many other species, landscapes and conservation themes. Karanth’s colleagues like Samba Kumar, Krithi Karanth, Vidya Athreya, Varun Goswami, Divya Vasudev, Devcharan Jathanna and Imran Siddiqui work on an amazing array of species, landscapes and conservation issues across India.

WCS-India also collaborates with the National Centre for Biological Sciences in Bengaluru to run a world-class master’s degree programme in wildlife biology and conservation. This programme led by Dr. Ajith Kumar, is turning out the next generation of capable, passionate conservationists, who are already making their mark across the country.

WCS-India is moulding the next generation of capable, passionate conservationists by collaborating with the National Centre for Biological Sciences in Bengaluru to run a world-class master’s degree programme in wildlife biology and conservation. Photo Courtesy: Imran Siddiqui, WCS.

The WCS programme brings in another intangible benefit – a sense of optimism in the currently grim wildlife scenario.

Karanth believes that “WCS’ work of nearly 30 years in Malenad shows that ecologically-fragile species like tigers and elephants can be saved, even in the face of increasing human populations, rapid techno-economic growth and modernisation of cultures. If we use the best science and deep passion to steer conservation in the face of these social changes, India can have even more abundant wildlife. What we need is a vision of an India with 10,000 wild tigers and the determination to find pragmatic solutions to make that vision a reality.”

Citizen Science

D. V. Girish was a teenager when he first travelled to Nagarahole on borrowed money to walk line transects in Ullas Karanth’s ‘boot camps’– as WCS’ rigorous citizen science programmes are often jokingly called. It’s been over 25 years, and Girish still walks transects every year, with the same drive and enthusiasm, all the while mentoring eager young naturalists. A coffee planter near Chikkamagaluru, Girish has fought relentlessly to safeguard the Bhadra-Kudremukh landscape from mines, dams, mega-tourism schemes, ill-conceived micro-hydel and windmill projects.

He played a key role in the successful resettlement of 17 villages out of Bhadra under the leadership of dedicated park warden Yatish Kumar and deputy commissioner Gopalakrishna Gowda in 2002. Today, the Bhadra relocation project stands as a benchmark for fair and just resettlement programmes across the country.

Girish is a sterling example among the 4,000 odd amateur naturalists, photographers, engineers, journalists, lawyers and people from varied backgrounds that WCS-India has inspired and nurtured over three decades through its citizen science.

All such volunteers are trained in wildlife-monitoring techniques as well as exposed to conservation advocacy practices. Today, many have gone on to become strong defenders of wildlife. Involving ‘ordinary’ citizens, harnessing their love for nature and giving it focus and direction has been Karanth’s major initiative with far-reaching impacts, as corroborated by a Duke University-study led by Mackenzie Johnson. The study showed that WCS citizen science massively boosts environmental awareness and focused local advocacy generates broader public support for local conservation efforts. It also reported direct impacts on conservation including professional career shifts among many volunteers, who have become full-time conservationists and wildlife scientists.

Seen here at a relocated village site, D. V. Girish played a key role in the resettlement of 17 villages out of the Bhadra Tiger Reserve. Photo Courtesy: Ullas Karanth.

Seen here at a relocated village site, D. V. Girish played a key role in the resettlement of 17 villages out of the Bhadra Tiger Reserve. Photo Courtesy: Ullas Karanth.

Voluntary Relocation

P. M. Muthanna admits to a certain amount of ambiguity when in 2000 he joined the WCS’ effort to support the Government’s voluntary relocation of 1,550 tribal families marooned within the Nagarahole Tiger Reserve. He knew the exercise was politically volatile, and faced resistance from ‘social activists’ of various hues, the popular media, and, an often lethargic officialdom.

But what, thought Muthanna, if the people themselves wanted to go? Wanted a life different from this miserable existence, isolated in remote jungles, deprived of basic facilities and locked in perennial conflicts with elephants, tigers and other wildlife whose shrinking habitats they encroached?

Muthanna got working with the first 150 families, who had already moved out with support from Project Tiger. WCS partnered with official efforts and offering additional hand-holding to the relocated villagers, besides facilitating access to better health care, education, vocational training and inputs for agriculture and markets. The emphasis was on empowering the tribal beneficiaries and building leadership from within.

Fifteen years later, Muthanna can look back on his work with satisfaction. The over 500 families who have relocated in the past decade, have steady livelihoods and rising incomes, access to education, electricity, markets, and exercise political muscle. From being isolated and uneducated, they are now represented in village committees. A new and articulate leadership has emerged from their own ranks, who are now pressing for similar assistance to others remaining within the park – and not just in Nagarahole but also in other forests.

Such government-financed voluntary relocation programmes are time consuming and difficult. Conservation NGOs, particularly international ones, generally considered them too ‘hot’ to be dealt with. Karanth’s WCS programme recognised early that, if properly implemented, voluntary relocation, was a win-win situation for both people and wildlife – yielding inviolate core areas and consolidating wild habitats, while securing a better future for marginalised communities.

WCS now supports voluntary resettlements across all its conservation sites, which include Nagarahole, Bhadra, Bandipur, Kudremukh, Anshi-Dandeli, Wayanad, Amarabad-Nagarajunasagar and Mudumalai.

P. M. Muthanna joined the WCS effort to support the government’s voluntary relocation of 1,550 tribal families marooned within the Nagarahole Tiger Reserve in 2000. His work involved hand-holding villagers (top) to enable a successful relocation at their new sites and interacting with local leaders of various hues. Photo Courtesy: WCS India

P. M. Muthanna joined the WCS effort to support the government’s voluntary relocation of 1,550 tribal families marooned within the Nagarahole Tiger Reserve in 2000. His work involved hand-holding villagers (top) to enable a successful relocation at their new sites and interacting with local leaders of various hues. Photo Courtesy: WCS India

P. M. Muthanna joined the WCS effort to support the government’s voluntary relocation of 1,550 tribal families marooned within the Nagarahole Tiger Reserve in 2000. His work involved hand-holding villagers (top) to enable a successful relocation at their new sites and interacting with local leaders of various hues. Photo Courtesy: WCS India

P. M. Muthanna joined the WCS effort to support the government’s voluntary relocation of 1,550 tribal families marooned within the Nagarahole Tiger Reserve in 2000. His work involved hand-holding villagers (top) to enable a successful relocation at their new sites and interacting with local leaders of various hues. Photo Courtesy: WCS India