Women for our Wilds

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 35

No. 6,

June 2015

By Janaki Lenin

In an expansive essay, Janaki Lenin traces the contribution of Indian women to wildlife conservation and research. Covering the length and breadth of the country, she follows inspiring stories, formidable challenges, epic adventures and reveals the motivations of intrepid women in search of the priceless reward of experiencing wild nature first hand.

J.Vijaya travelled to places such as Bhagalpur, Bihar, looking for turtles where even men feared to go. In 1981, she was only 22 years old when she began mapping areas where hunters had wiped out turtles, and to which rivers they had shifted their operations to feed the markets of Bengal. Her graphic black and white photographs shook readers of India Today magazine as well as Prime Minister Indira Gandhi’s conscience.

In Kerala, she roughed it in a cave while studying the enigmatic cane turtle. Her only companions were Kadar tribals in a nearby settlement. One of India’s most adventurous women field workers, she was a protégé of my husband, Rom Whitaker. Although I heard of her legendary exploits, she’s relatively unknown outside of the little community of reptile aficionados.

I couldn’t imagine how Viji overcame the rigours of living alone a dozen years before I stepped into a jungle. My first experiences of the forest weren’t traumatic but I was uncomfortable. I had the luxury of being with an experienced naturalist, and I still feared everything from unpredictable beasts to misbehaving strangers. It took many months of learning about animals before I adjusted to life in the forest, and many more months before I learned to be a happy camper.

Viji was India’s first woman herpetologist, but not the first woman field worker in India. There were other pioneers before her like Priya Davidar and Usha Lachungpa, both of whom studied birds in the late 1970s. “This was a time when there was little serious work being done in the field. There were not many men or women out there,” says Rom.

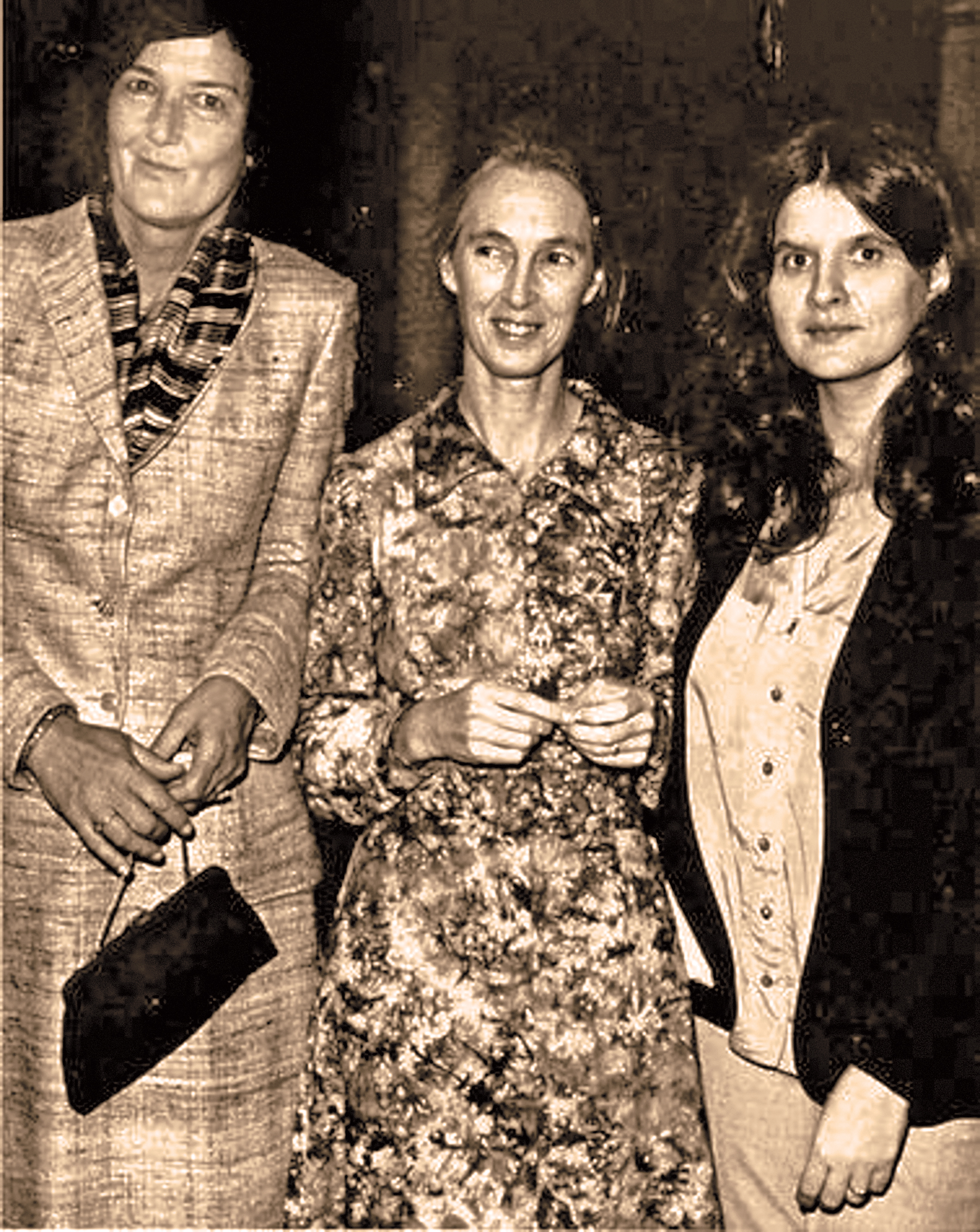

_1615185342.jpg)

India’s first woman herpetologist J. Vijaya lived alone in a cave in Kerala for several months at a time while studying cane turtles, far from any help should anything have happened. Photo Courtesy: Zai Whitaker.

Breaking in

Elsewhere, women were pushing frontiers, undertaking studies on the natural world. Sylvia Earle plunged underwater to study marine life, Jane Goodall brought new understanding of primate behaviour, and Rachel Carson turned the tide against the chemical pesticides industry. Generations later, they would become global role models and icons for young people.

India’s wildlife heroes then were Indira Gandhi and a wildlife-tolerant Rajasthani community called the Bishnoi. Bishnoi men allowed wild herbivores to eat their crops while their women went to the extent of suckling orphaned chinkara fawns. Both the Prime Minister and Bishnoi villagers are well-known to readers for their contributions and fostering of wildlife. But what part did ordinary women with neither the overwhelming political power nor the religious background play?

There were two strikes against women who wished to work in wildlife: society was old-fashioned, and wildlife research and conservation didn’t figure among career options. To the average person, forests lay beyond the pale of civilisation.

Ghazala Shahabuddin, an ecologist, says of the 1980s, “My extended family and friends’ view of wildlife conservation was, ‘This can’t be a job. You have to do something serious like medicine or administrative services.’ It was considered a very unusual field for a woman.”

Wildlife biology courses were offered only in a couple of institutions that accepted a handful of students a year. Ghazala travelled all the way from Delhi to Pondicherry to do her Masters. She says, “I come from a conservative Muslim family for whom the idea of women travelling and living alone was anathema. My mom was supportive but my dad was conservative and hated the idea of me going to Pondy for two years.” The two-day train ride to Pondicherry was the first time Ghazala travelled alone, far from home. Her father refused to talk to her before she left. “I cried all the way to Bhopal.”

Once Ghazala enrolled at the university, she says her father tried to coerce her to return by withholding funds for a semester. She was forced to borrow money from friends. She says, “This was the first time I had to rebel against my father. But ironically, he was instrumental in creating my love for wildlife. When I was a child, we travelled to remote areas, on foot and by car. We visited many sanctuaries in India and abroad, and we had an early exposure to forests unlike other kids.”

Protecting nature is of foremost importance for the Bishnoi community of Rajasthan with their women going to the extent of suckling orphaned chinkara fawns. Photo Courtesy: Vijay Bedi.

The other problem!

Getting consent from their families was only the first gauntlet. Women researchers faced challenges in the field. I thought decrepit staff quarters with primitive or no toilets, and the lack of basic comforts would figure prominently. I didn’t hear a whimper of complaint on that score. Instead, some women had to confront a different predator in the jungles: men.

Lalitha Vijayan, former director of Sálim Ali Centre for Ornithology and Natural History, recounts, “At one time when I was working alone in the forest (in Thekkady), I was harassed by a gang of hooligans. I ran into the rangers’ office. On another occasion, a rowdy-type of person cornered me in a gorge until I could not walk at all. The look on his face was horrible. I shouted out to my field assistant, “Raja, come with a knife,” and the chap ran away. Animals are no problem at all. Even if elephants are there, we know how to deal with them. Once a male elephant ran after us, we gave him way and he went off. That wasn’t as scary as human behaviour.”

This is a problem even now. Prerna Singh Bindra, conservationist and writer, says, “I have faced situations – and a few scary ones – where men have tried to take advantage of the fact that I was alone in a forest. But then I have faced that even in Mumbai or Delhi. It is intimidating at first, but as you grow older, you learn to deal with it. You fight back. There’s no other option.”

I expected harassment of women, who often work alone, to be par for the course, but surprisingly, it’s not the norm. Ghazala, Vidya Athreya, and Arati Rao, who between them have worked in many parts of the country, have no tales of unwelcome attentions.

Insecurity may have been a major deterrent in the past. In recent years, more and more women biologists have entered the field, and they choose to do their fieldwork in remote locations.

One camp I visited in Baratang, Andaman Islands, was so primitive that I wondered how swiftlet biologist Akshaya Mane lasted more than a day. She and her field assistants had to haul drinking water everyday from two kilometres down a steep, slippery slope.

Despite arduous field conditions, women biologists seem to be everywhere, studying elephants, lions, and birds and being voluble with their opinions. I could swear women biologists outnumber men.

However, Ajith Kumar, Director of the WCS-NCBS Masters in Wildlife Biology and Conservation programme, says women number less than half of the students. “Compared to other lab-based disciplines, there are far fewer girls in the course. I find that girls have been much more engaging with the public through print media.” I expect this is the trend in other wildlife biology courses as well.

A career for all?

Although there are a few women biologists from small towns, most of them come from urban centres. Why weren’t women from more disadvantaged backgrounds willing to opt for a career in wildlife? Ghazala says, “My family was well-off so I was not too concerned about the uncertainty of a comfortable job or secure career. It helped that I had a family to fall back on, even if I didn’t earn much.”

Vidya agrees, “It has no career, no money, no assured job. For none of us is that important. We are a privileged bunch.”

Some women from rural areas do enlist for fulltime fieldwork in the lower rungs of the forest service as guards and watchers. They confront armed poachers, conduct raids, and fight fires.

Gopa Pandey, one of the first Indian Forest Service women officers, says, “A woman of 28 to 35 years of age covers an area of 10 to 20 sq. km. all alone on foot. They have kids and they don’t have support. Are they safe? We should not live in a fantasy or wrong notion that women can do anything. Rangers have to work 26 hours a day. They are actually super-men. Women range officers have to wear uniforms with belts even when they are pregnant. It’s a big gang up against them.”

Compared to these gutsy women, my occasional forays in the forest seem like child’s play. Yet, women from other professions often ask me if I’m not scared to travel alone.

If I wasn’t a filmmaker and a writer, and I wanted a job that was in close contact with wildlife, I would choose to be a naturalist in the tourism industry. I certainly can’t withstand the rigours of higher education, and I would guess there were many women who feel the same way. As a naturalist, you get paid to travel into parks and sanctuaries every day and see some amazing animal behaviour. But look around and you realise women naturalists are a rare species.

India’s modern wildlife movement owes a lot to to the legal and institutional framework that was created under former Prime Minister Indira Gandhi’s leadership. Photo Courtesy: Public Domain.

S. Karthikeyan, chief naturalist of Jungle Lodges and Resorts says, “I’ve trained only one woman in the past 12 years. She got married and quit. Guests drink in the evenings. Maybe women don’t think tourism is a suitably safe occupation.”

Motherhood is another stumbling block in women’s ability to do fieldwork. Some women choose not to have children, or put their careers on hold until their children grow up. But others take it in their stride, like Kaberi Kar Gupta who carried her baby daughter to the forests of Kalakkad-Mundanthurai while she did her fieldwork. She says studying primates and watching their childcare influenced her decision.

Another primatologist Anindya Sinha and his wife Kakoli Mukhopadhyaya also carried their children to Bandipur. Anindya says, “People fuss over their children a great deal more than necessary. Kids are tough and resilient. Our children played with their toys in the rear of the jeep while we studied bonnet macaques. It taught them to be independent from a young age.”

Arati Rao, a photojournalist, says, “I know some women who are such good photographers, they could be professionals. They just won’t do it. They say, ‘But I have a child. You don’t realise I need to be there when she comes home.’ There is a burden of guilt we carry around and we really don’t have to. I have a daughter too and my husband and I take turns. If you want something badly, you have to figure things out – what is important? What’s your priority? There can be freedom but some women still remain shackled.”

After overcoming all these obstacles in the field, life doesn’t get any easier for women. Priya Davidar, Professor at the Department of Ecology and Environmental Sciences, Pondicherry University, says, “I had no problem in carrying out field work, but working with my male colleagues was enormously challenging. I faced gender harassment – preventing women from carrying out research, interfering with their students, preventing women from participating in meetings, and so on. It happens to men as well, but less virulently because they are considered to be more powerful. It’s very widespread among all fields of research and is a result of professional jealousy.”

Such pettiness doesn’t just afflict research, it also pervades other aspects of conservation. Gopa says, “We have to work twice the amount to get one-quarter the recognition that men get. They routinely look down upon us like we are small, we don’t count. Most women officers have faced this over the years. It’s very challenging; it’s not for every woman. There’s a whole army against you on the other side of the fence.”

Women leaders

Prerna, who served in several committees such as the National Board for Wildlife (NBWL), says, “Most men find it hard to take women in a leadership role. I had to work that much harder to be taken seriously. There was this typical ‘boys club’ attitude, like ‘How can this chit of a woman…’ if you know what I mean. It could be petty – personal egos and jealousies – or the fact a woman was actually achieving something on her own merit. But it got daunting at times. There was a perceptible effort to pull me down when I took on the leadership role on some issues. But there are rare and wonderful exceptions when men appreciate and support you.”

Few women hold leadership positions even in NGOs. The few that do, head organisations that they established like Zai Whitaker at Madras Crocodile Bank Trust and Belinda Wright of the Wildlife Protection Society of India. One of the few exceptions is Sunita Narain of Centre for Science and Environment, who joined the organisation two years after it was set up by Anil Agarwal.

Ghazala says, “Whether it’s a marketing job, wildlife job or teaching job, there is discrimination. If you work hard and have willpower, it’s not that difficult. If you have support from close friends and siblings it makes it easier (to surmount the challenges).”

Ardous field conditions haven’t deterred women biologists such as Akshaya Mane from following their true passion. Photo Courtesy: Akshaya Mane.

What if getting a job itself is a problem? Discrimination prevents women from getting jobs, tenure, and promotions. For instance, take a look at the composition of the editorial board of Current Science, one of India’s premier peer-reviewed science publications. Eleven of the 12 members who handle ecology and conservation are men. All seven associate editors are men. In fact, there are only three women in the entire 59-member board.

Needless to say, the editor is also a man.

Science is not the only area where women are under-represented. Conservation policy and decision-making suffer the same malaise. Prerna says, “I realised that the ‘glass ceiling’ we hear about in the corporate world exists in this field as well. I found a paucity of women at decision-making levels. For instance, in many meetings in the MoEF or the Standing Committee (of the NBWL), I used to be the only woman.”

In the forest service, Gopa Pandey says, “There are about 300 women out of 3,000 officers in the country.”

Women who surmount all these challenges – braving the elements, gender harassment, and discrimination – become tougher cookies. Ghazala says, “When you get out of these struggles, you feel that much stronger and more empowered than a man would feel.”

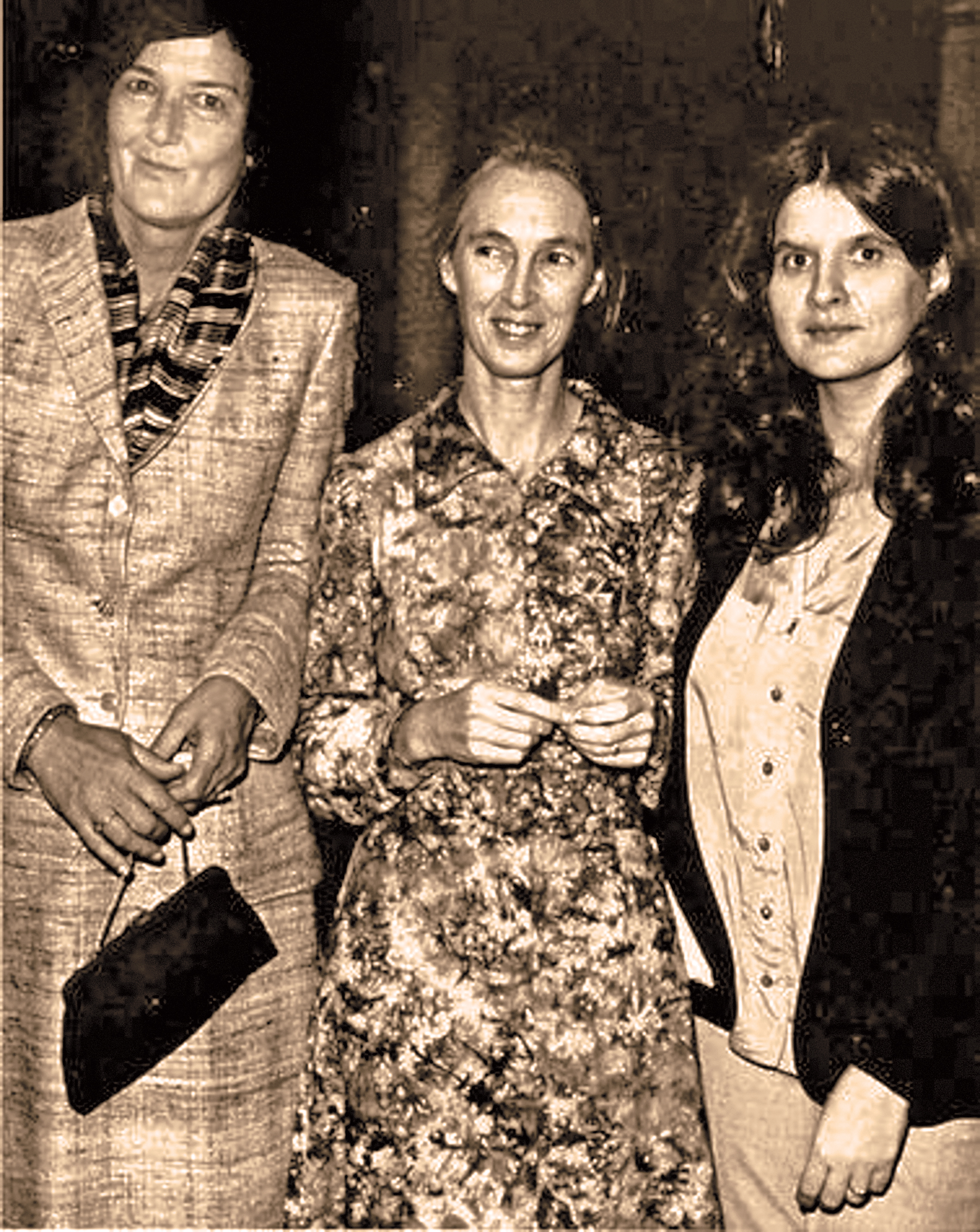

BirutÄ— Galdikas, Jane Goodall and Dian Fossey, who studied orangutans, chimpanzees and gorillas respectively, under the aegis of anthropologist Louis Leakey, came to be known as ‘The Trimates’. Photo Courtesy: Public Domain.

Empathy – a differentiator

Others might then belittle women’s successes, adding insult to injury. They assume that women who are successful must have had it easy. Vidya Athreya, who studied leopards in the farmlands of Maharashtra, says, “They said the Forest Department was nice to me because I’m a woman. I saw men researchers who got along fine with the Forest Department too.”

Prerna also faced similar comments. “Some said, ‘She must be pals with the minister.’ ‘Officers will give you access because you are a woman’ – I hear that often. I grant you that it might get you a meeting. But beyond that, it boils down to your work – your knowledge, research, conviction – and how you negotiate and convince them of the issue at hand.”

Arati counters, “In terms of empathy, women can connect with women better, and see environmental, social, and health issues from a shared perspective. But I know men who are empathetic. On the other hand, I

have heard of women photographers being insensitive.”

Did being a woman not bring any advantages to the job? Did women work differently? Vidya says, “One word: empathy. As a woman, I’m empathetic to people who lost their kids to leopards. I’m a mother too. If you don’t deal with people, you can’t do anything for leopards.”

Sonali Ghosh, a forest officer who served in Kaziranga, Chakrashila, and Manas, says, “People were at ease with me, especially in Assam. They really open up. Forest guards chat and feel comfortable. Women are better at communication. I really feel this is where we excel compared to our male counterparts. Even within the department, lower rank officers are happy to have a woman boss because we stick to time, we are happy if you have done your work, and we are not into bureaucratic stuff. I’ve seen this across departments.”

Priya says, “I think women have diluted this macho culture of self-aggrandisement and monopolisation of charismatic animals which is not healthy for wildlife research and conservation.”

Could women feminise conservation? Was there something to the old eco-feminist argument about women being more closely connected to nature? But my husband is much more in tune with nature than I am.

I’ve been asked if being a woman influenced my writing. How could being a man, woman, transgender, or one of the other 50 plus gender identities recognised by Facebook for instance, influence one’s research, writing, or photography? I thought it was a silly question.

Gender and class

Shekar Dattatri, a wildlife filmmaker and conservationist says, “Gender bias may have kept some women away from fieldwork in the past, but I don’t think gender has anything to do with their impact on conservation.”

Arati says looking at one’s work through a gender perspective “seems to undercut intelligence, undercut merit.”

I could see where Arati was coming from. To prefix ‘woman’ to one’s career seems to put one in a sub-category. I want to be judged as a journalist, not as a woman-journalist.

Maybe Arati and I are speaking from positions of privilege. Protecting forests for a pay cheque isn’t the only way women turn conservationists. Across India, thousands of women, often illiterate, safeguard forests and wildlife as a way of life and securing their livelihoods. They struggle against class, caste, state, and private companies, while having to live within a patriarchal society.

The most famous environmental movement was Chipko. In 1973, women of a remote Garhwal village, Mandal, in the Himalaya, saved 300 trees from being hacked down by a timber contractor. Villagers’ appeal to cut 10 trees to make agricultural implements was turned down, but the contractor was allowed to cut trees for a manufacturer of tennis rackets.

The men of the village were away when loggers arrived. Village women hugged the trees and dared the men to cut them down as well. The unnerved contractor backed off. This was one of the flashpoints in the villagers’ struggle to wrest forest resources from the state. Similar movements to save forests sprouted not only in nearby villages but as far away as Karnataka where it took the name Appiko.

Poor women are victims of environmental degradation, and it is said that their desperate circumstances make them take radical actions. Environmentalism of the poor, Anil Agarwal famously called it. But the women of Mandal didn’t materialistically list the benefits of the forest as, “Firewood, fodder, and fruits.” Instead, they displayed their astute understanding of ecology when they chanted, “Soil, water, and pure air; sustain the Earth and all she bears.”

Thousands of villagers, many adivasis, manage community forests in central India, like the Dhongria Kondh of the Niyamgiri Hills. They decide which forest produce to harvest, who can harvest, and when.

Kalpavriksh documented the case of a 30-household-village of Kondh tribals called Dangejheri, Nayagarh district, Odisha. In the 1970s, industrialisation had completely denuded the area. Villagers nurtured the barren hills back to life. When the timber mafia moved in and the Forest Department failed to aid the residents, women, armed with sharp implements, confiscated the illegally-harvested timber. Since then they formed the Maa Ghodadei Mahila Samiti to manage their 80-hectare community forest. Women’s confidence surged with their success. Now they are an inspiration for women of neighbouring villages.

Hundreds of van panchayats across Uttarakhand, with the active participation of women, are similarly committed to nurturing forests. Rural women also joined in mass protests against mining, dams and other forest-destructive industries.

Perhaps the impact of gender seems inconsequential in research, policy, and the humanities, but it’s a big factor in governance. Economist Bina Agarwal studied the management of community forests in Gujarat and Nepal. In her book Gender and Green Governance, she writes that when more women are involved, they are able to enforce strict conservation rules and impose harsher penalties. She argues that forests protected by all-women groups are in better condition than others.

Women in research and conservation have to reach a critical threshold before we realise the impact of gender. To achieve that, we need more plucky women like these to tread the wild path.

In the 1970s, the Chipko movement, saw villagers, especially women, stand up against commercial logging operations that threatened their livelihoods. Photo Courtesy:Ceti/ Public Domain.

DURGA SHAKTI

On December 4, 2014, as an audience of over 1,000 sat glued to their seats at the National Centre for Performing Arts, the women of Maharashtra’s Special Tiger Protection Force marched onto the stage in perfect synchrony for a brief moment in the spotlight. Here, at the 15th Sanctuary Wildlife Awards they were honoured by the Chief Minister of Maharashtra with a Special Tiger Award.

Far from the glitz of the NCPA show, these women deal in the business of guts, grit and grime in the course of protecting the state’s vulnerable tiger forests. Selected after a rigorous process that includes both physical endurance and aptitude tests, their skills have been whittled and polished to transform them into daunting protectors of the wild. In their olive-khaki uniforms, they patrol pathless miles in search of poachers and snares, and spend their free time training in hand to hand combat with paramilitary commandos.

Committed and fearsome, unmindful of archaic social norms, they are the embodiment of not just unadulterated, feminine power in the interest of tiger conservation, but the gradually evening scales of job division in the conservation world.

Author: Janaki Lenin

_1615185342.jpg)