Women in Herpetology

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 41

No. 4,

April 2021

By Ashwini V. Mohan & Sneha Dharwadkar

Consider these: A child catching a lizard, a student researching the ecology of turtles, a professor running a training workshop on handling snakes. Now stop and think about the gender you imagined in each of these images.

The study of reptiles and amphibians is known as herpetology, an umbrella term that encompasses varying facets of this science, including ecology, behaviour, conservation, education, evolution and more! Be it squatting by a roaring forest stream observing breeding frogs or creating public awareness to mitigate snakebites, or even pipetting out DNA in the laboratory to uncover how different species are related!

We received a resounding YES from over 18 women and four men in the field of herpetology, when we asked them if men were more represented than women in this field.

Herpetology is a field known for the display of machismo. Like other scientific fields of study, herpetology was dominated by men for centuries mainly due to gender-conforming roles dictated by society. Fast forward to the 21st century, it comes as a surprise that this gender divide not only still exists but thrives. It is a daily life hurdle for many women who dream and aspire to be scientists. Conversations on gender bias and discrimination across Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM) fields have finally become mainstream. All these discussions agree on one thing – that bringing about gender equity would lead to a better future for STEM. Many institutions have begun to rectify gender bias, and an increasing number of studies have highlighted the issues women researchers continue to face. We interviewed herpetologists, largely women, about the factors behind this continued gender bias, and their responses repeatedly led us to some prevalent issues we discuss here.

Dr. Rachunliu G. Kamei, digging to find caecilians (legless amphibians). Dr. Kamei has pioneered research on caecilians of Northeast India. Photo courtesy: Dr. Rachunliu G. Kamei.

Perceptions Of The Field

Dr. Anuradha Batabyal, a Postdoctoral Associate at the University of Calgary, who studied the behaviour of the Peninsular rock agama Psammophilus dorsalis in India, pointed out that machismo is considered a necessary trait to work in herpetology. Several others also used the word ‘machismo or machoism’ to describe why men are more visible and popular among the public, particularly on social media platforms. The machismo factor is certainly responsible for the scanty representation of women herpetologists in the media.

This has consequences for aspiring scientists. Spoorthi, an undergraduate working to reduce human-snake conflict in parts of Karnataka, recalls how she hardly knew of women in this field and felt the lack of role models. The few workshops she attended always had men as resource persons and we were not surprised to hear that. Most herpetology workshops in India are private and are taught by men. While motivated by positive values of public outreach and education, “manels” with no women professionals contradict the inclusive aims of these workshops. This phenomenon extends even to the only government sponsored SERB School of Herpetology (funded between 2007-2016 for an annual training programme) where the pool of resource people had few women.

Spoorthi Shetty, a young herpetologist working on community outreach through snake rescues and teaching in Karnataka. Photo courtesy: Spoorthi Shetty.

Barriers To Career Advancement

A cursory glance at the professors of herpetology across India reveal that there are a mere handful of women professors actively teaching and conducting research. We interviewed Dr. Maria Thaker, associate professor at the Indian Institute of Science, Bengaluru. Dr. Thaker’s lab focuses on the behavioural ecology of different animals, but mostly on colourful rock agamas from our Deccan Plateau. When we asked what lured her into this field of study, she confessed that nothing makes her heart sing the way lizards do! Having survived the ‘leaky pipeline’ (from a college degree to a tenured academic position), Dr. Thaker pointed out that the age limit imposed as an eligibility criterion to apply for academic positions is one of the factors that effectively hinders women to climb this ladder. The arbitrary vertical climb in a career path, especially for women in academia, is no easy ascent. Life choices such as marriage and children often hinder career advancement for women. The ability to relocate geographically for short-term career opportunities, such as postdoctoral positions, significantly shapes a researcher’s scientific network, experience, and expertise. This, in turn, influences a potential professor’s application, rendering a woman ‘less experienced’ and ‘less qualified’ compared to a man of her age. When we asked about the whereabouts of his women peers from college, Dr. K.V. Gururaja, a batrachologist (a scientist working with amphibians) based in the Srishti Manipal Institute of Arts, Design and Technology, Bengaluru, replied, “We have a lot of women as students, but then as we go up in the academic hierarchy, the number reduces.” While many researchers (of all genders) shift fields, women seem to ‘drop-out’ much more frequently.

Dr. Anuradha Batabayal (left), a Postdoctoral Associate, University of Calgary, and Associate Professor Maria Thaker (right), Indian Institute of Science, Bengaluru, with a peninsular rock agama Psammophilus dorsalis. Found in the rocky hills of peninsular India, the male changes colour dramatically during the breeding season. Its head and back turn a bright yellow-orange while the rest of the body turns deep black. Photos: Dr. Anuradha Batabayal & David Bossard/Public Domain.

Conservative mindsets and assigned gender roles are other limitations that women face. Shaleen Attre, co-founder of Indian Snakes points out that there are more women in conservation now than ever before, but they are almost always given project managerial and fundraising roles. Shaleen was denied fieldwork in her previous jobs citing risks and safety, while men in her group were routinely out in the field. Some women were assigned laboratory-based work without a choice, either due to their expertise in laboratory work or because a Principal Investigator deemed them fit only for that. Shaleen further points out that women don’t speak of their work often in public forums and social media, unlike men, and this limits their recognition. This certainly impacts networking, job and funding opportunities.

Anuja Mital tells us that the next obstacle are the bosses themselves. Project leaders often do not hire women, deeming them unfit for fieldwork, or safety risks, or assuming they will prioritise “family”. These reasons are not openly expressed, but are often whispered in the community. Brinky Desai studies the endocrine physiology of muggers Crocodylus palustris, one of a handful of women in India studying crocodiles. She was denied volunteering opportunities, which hindered her work experience early in her career. A senior herpetologist suggested she was more suitable for a desk job than hardcore fieldwork in herpetology. We think no less of desk jobs, yet we would like the opportunity to make our choices. Women are routinely denied volunteering positions or job opportunities they would like because of the sickening discrimination that persists in our society and is perpetuated by decision makers!

Wildlife biologist Brinky Desai’s research studies focus on the endocrine physiology of muggers Crocodylus palustris. She is one among a handful of women studying crocodiles in India. Photo: Bernard Dupont/ Public Domain.

When we explored how women were treated by their peers and other stakeholders (the public, permit authorities, funding authorities and so on), several women, including us, found our opinions held less value than a man’s, even when it was the exact same opinion.

Sarita Fernandes, a coastal policy scholar and a marine naturalist in southwest India told us the stories of struggles through the community-conservation model in turtle nesting beaches of Goa – Morjim, Agonda and Galgibag and the challenges she faced in her initial research career working on olive Ridleys. Some women even pointed out the trouble they faced from the authorities including forest officials.

Sarita Fernandes, a coastal policy scholar and marine naturalist in southwest India conducting a workshop on turtle conservation for school children in Goa. Photo courtesy: Sarita Fernandes.

The Issue of Safety

This is a major issue in India, whether in isolated forest patches or flanking forests outside large cities. Safety and sexism are tightly interwoven especially since most people consider a woman incapable of protecting herself. The solution is not to exclude an entire demographic from fieldwork, killing opportunities for the very gender that is being ‘protected’ but rather in creating safe working spaces.

Aside from fieldwork, threats in offices and workspaces too are largely ignored. Unfortunately, the #MeToo movement never reached the ecology and conservation bubble in India. One herpetologist shared her memories of harassment, verbally and mentally by a colleague for years, something other men in the field even supported. Topics such as harassment of any kind are delicate and often tricky to approach even within a circle of colleagues. Few women are willing to talk about it, and most stay silent because of anticipated societal stigma and potential professional consequences. With all too few women as mentors in Indian herpetology, such incidences are excruciatingly difficult to narrate, or seek support.

Equality cannot be a reality without institutional reform and policy-level support, both in the academic and the conservation sectors working for herpetology. Recently, the Science Policy Forum conducted a series of panel discussions to propose a Science Technology and Innovation Policy (STIP) that could potentially ensure equity and inclusion. They came up with a set of recommendations to make STEM more inclusive to women, such as relaxing age limits for applications and providing institutional support for women through motherhood. Implementing these within the contexts of subfields such as herpetology will improve the prospect for women to gain leadership positions and pave the way for a new generation of herpetologists.

_1617283394.png)

Priyanka Swamy, a Doctoral student in Mysore University studying Malabar pit vipers, measuring snake specimens in a museum collection. The Malabar pit viper Trimeresurus malabaricus is a Western Ghats endemic snake. This nocturnal snake hunts using its heat-sensing pits, which help gauge variation in temperature to attack prey in the dark. Photos: Priyanka Swamy & Public Domain.

If We Can Do Something Different From Men, Should We?

Most women in our field of research, including us, feel we do not do anything differently compared to men. Dr. Barkha Subba, a batrachologist at the Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and the Environment (ATREE), Bengaluru, believes that this is a complicated question without a universal answer because as individuals, we function differently. However, she does feel that men tend to be more aggressive (in terms of career growth and publicising their work) and that this helps them grow quicker. More often than not, women tend to be agreeable. We wonder if this might be a strategy we employ to avoid trouble. Because experience shows that when we women try to voice our opinions, we are often judged in a negative light.

On the brighter side, in India, we have several young men in herpetology who believe in inclusion and equity, and their work reflects efforts to address this issue. We interviewed Dr. Nitya Prakash Mohanty, currently a postdoctoral researcher at the Indian Institute of Science who pointed out that the first step was to recognise that there is a problem. What could be better than data-driven findings, we thought, because such findings are unambiguous.

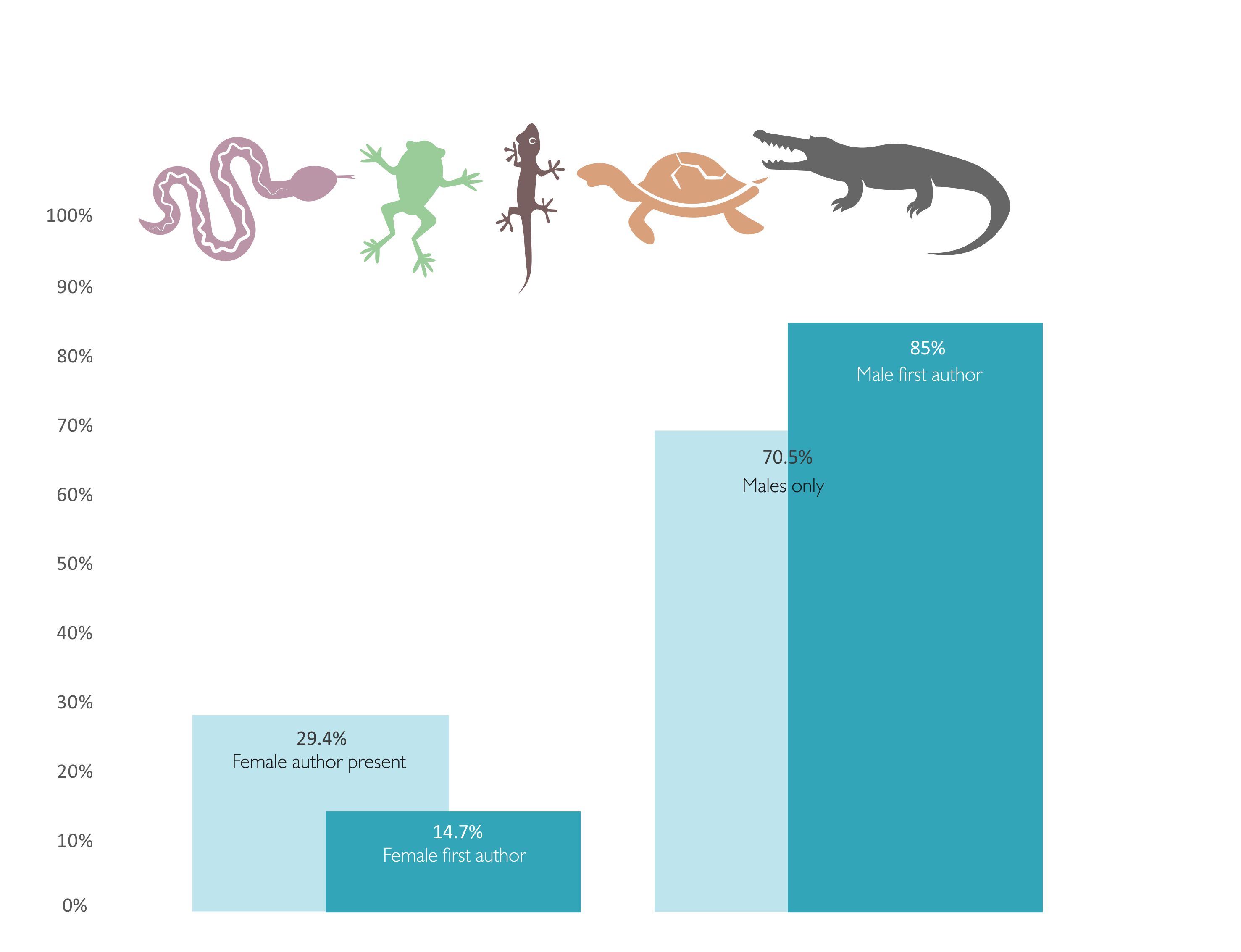

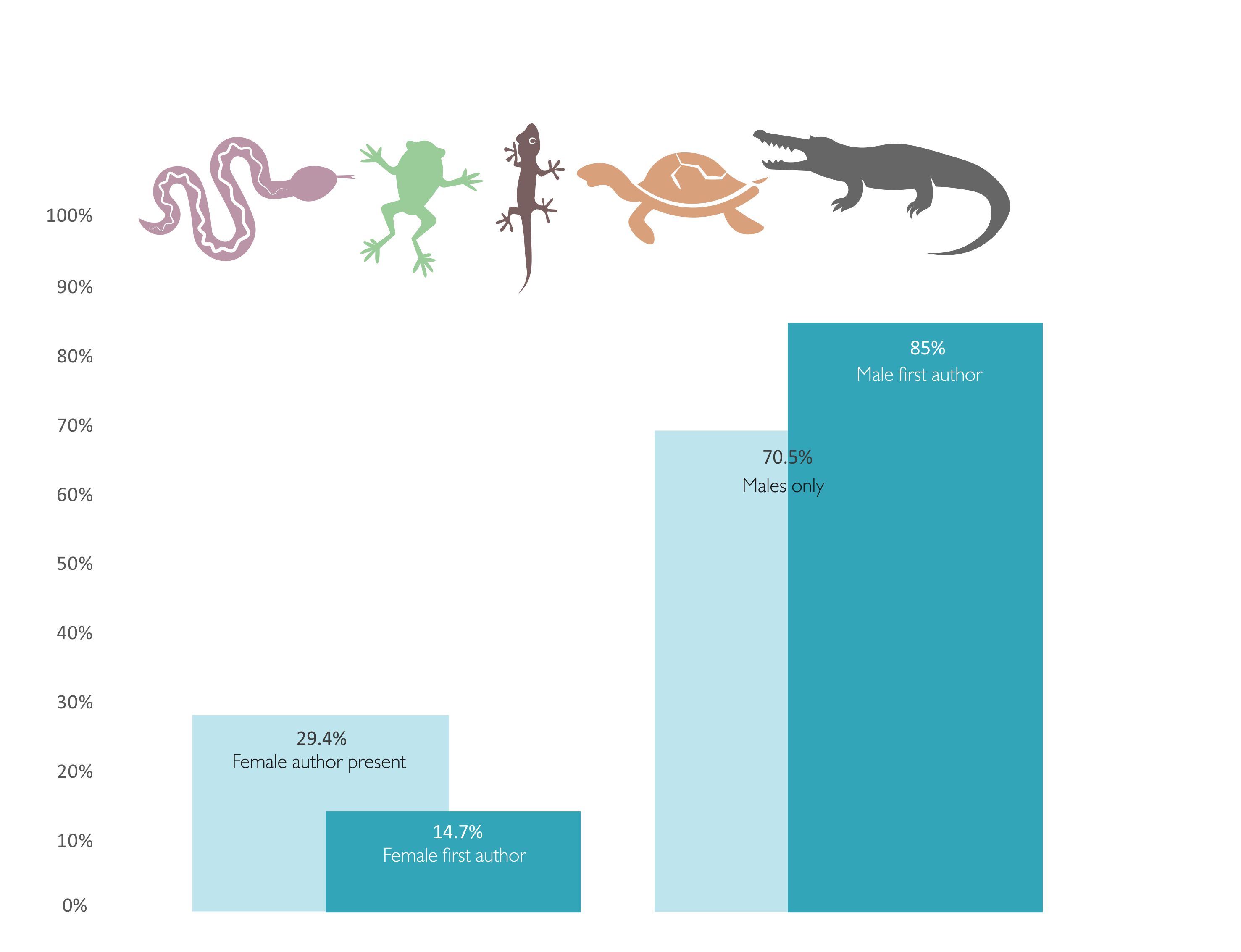

One classic way to check how women fare in the academic side of herpetology is to observe the number of publications authored by women. Peer-reviewed scientific publications are key outputs from research projects. We dug into the research publications of Indian herpetology starting from 1947 (1,175 publications in total) and found that 85 per cent had male first authors and 70.5 per cent of the papers only had male co-authors. Research also indicates that the skew between male and female authors persists across studies on various taxa within herpetology. More generally, people tend to favour working with and hiring those who remind them of themselves. This is problematic because when the people making decisions about hiring and collaborating are all men, a vicious cycle emerges, with men hiring men, eventually leading to collaborations between all-male groups.

Women in herpetology in India may be few but are certainly not new. Although this trend could emerge from the field having historically low representation of women, they have played key roles in documenting and protecting wildlife.

This dataset is part of an ongoing project to study trends in herpetological research in India (Cyriac et al.). The authors have assessed over 1,000 research papers to obtain these figures. Courtesy: Authors (Cyriac et al.)/ animal vectors from vecteezy.com.

The Past And The Future

A notable figure is Jeganathan Vijaya (1959-1987). Vijaya was a turtle biologist in the 1970s, when the illegal trade in wild turtle meat was rampant. She visited and documented turtle meat markets at great risk. These photographs eventually caught the attention of the late Prime Minister of India Mrs. Indira Gandhi which led to the legal protection for turtles and tortoises under the Indian Wild Life (Protection) Act, 1972.

Most of us agree that women in herpetology have been increasing in numbers over the last one or two decades, and this trend will hopefully reflect in scientific publications in the course of time. We have grown not merely in numbers but are forming supportive communities that address issues in the fields of ecology, evolution, behaviour, conservation, wildlife awareness, under the larger umbrella of herpetology. We actively share work by our women peers to boost visibility and collaborative opportunities. The interviews we conducted for this article connected us to several women and their stories, leading to new friendships and fruitful collaborations.

_1617284093.png)

Jeganathan Vijaya (1959-1987) was probably the first recognised woman herpetologist in India. Her photographs of the olive Ridley slaughter in West Bengal prompted the legal protection of turtles and tortoises in India. She also rediscovered the Cochin forest cane turtle, which was renamed in her honour to Vijayachelys silvatica. She died at the young age of 28, of reasons unknown. Photo coutesy: Zai Whitaker.

However, the problem of inaccessibility is not limited to women alone. Careers in STEM remain accessible only to urban/ semi-urban India. Limited exposure to natural sciences and the lack of financial security offered by these careers tend to exclude both rural candidates, as well as those below India’s upper-middle socioeconomic class. This is true for virtually all branches of ecological sciences and conservation, largely because not many can afford an education that does not promise competitive financial returns. Apart from economic factors, career opportunities in such fields are few as well. Fortunately, digital communication and widespread Internet access is helping Science Communication (SciComm) reach extended spaces in the public arena. SciComm efforts are steadily popularising lesser known sciences including herpetology. Change, it seems, is indeed around the corner.

Science needs to be more gender inclusive and the different roles genders take upon themselves. Creating more access to higher education, funding for research, scholarships to support academic studies, all of these are necessary steps to level the playing field. We hope that the field of herpetology will not continue to be viewed as an unattainable or peculiar career choice for women in India. Lastly, it is pivotal that today’s herpetologists, vastly represented by men, take active steps towards shaping herpetology into a more diverse and inclusive field of science.

Authors’ note: This article was necessitated by ‘manels’, panels of resource persons consisting only of men in spite of several women in herpetology. We acknowledge that gender is a spectrum, however we could not consider non-binary genders in our authorship analysis due to respect for privacy and lack of information. We thank Pooja Gupta for the wonderful illustration accompanied by this article, Krishna Anujan and Anat Belasen for significantly improving the article by providing key comments, Vivek P. Cyriac for his initiative in collecting authorship data from scientific publications and Madhushri Mudke for her initial involvement with this work. Finally, we want to thank several women and a few men, who shared their honest opinions and stories, which provided valuable perspectives and insights.

Ashwini V. Mohan is a doctoral candidate at the Institute of Zoology, Braunschweig University of Technology, Germany. Her work investigates macro and micro-evolutionary trends of island reptiles in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands and other islands in the Indian Ocean. Sneha Dharwadkar is a turtle biologist working in the field of conservation, ecology, and community education over several years. She is the co-founder of Freshwater Turtles and Tortoises of India (FTTI).

_1617283394.png)

_1617284093.png)