On Sinking Land

First published on

August 02, 2023

By Shatakshi Gawade

Imagine a stacked pile of papers. Every time a single sheet is pulled out from the middle, the top sinks, imperceptibly. More sheets would of course lead to more sinking. In our case, the stack is the Earth’s crust, the removed sheet is extracted groundwater, pumped from deep borewells, and the sinking top layer is the surface we are on. Such a sinking surface – land subsidence – is the alarming reality in several parts of the country as groundwater extraction continues unabated.

Deep in the Bowels of the Earth

Groundwater is stored under the surface of the Earth in cracks and pores of rock and soil in structures called aquifers. An aquifer is a water-bearing rock that allows the groundwater to flow into wells and springs, which may flow into streams or lakes. Water seeping down into the soil recharges these aquifers. But the rate of recharge is different according to the type of rock, which is why the well may run dry if the extraction is higher than recharge, or land may subside.

Groundwater in (Alarming) Numbers

By some estimates, human activities are responsible for 77 per cent of the ground subsidence across the world, of which 60 per cent is attributed to groundwater extraction. With a fourth of the planet’s groundwater being withdrawn in the country, India is the largest user of the underground resource.

Groundwater provides 48 per cent of the water supply in Indian cities. U.S.A.’s National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) has recorded that in just the last decade, the groundwater in north India has decreased by 108 billion cubic metres. Such unabated, often unregulated, extraction of groundwater is causing land subsidence and recent research suggests is even tilting the Earth’s axis.

Researcher Shagun Garg found that land was subsiding in Kapashera, 10 km. from Delhi’s airport, at the rate of 17 cm. per year. He also observed sinking land in other parts of Delhi NCR. This corresponds with the over four metre decline in groundwater in some pockets of Delhi, in wells monitored by the Central Ground Water Board (CGWB) in November 2020 compared to the decadal average (2010-2019). CGWB has recorded a decline of about 33 per cent of groundwater in wells across India by upto two metres. A decline of over four metres has been observed in Dehradun, Ghaziabad, Indore, Allahabad, Kanpur, Lucknow, Jaipur, Vijayawada, Chennai, Coimbatore and Madurai.

_1691483644.png)

Groundwater being pumped at a farm. Human activities are responsible for 77 per cent of the global ground subsidence, of which 60 per cent is attributed to groundwater extraction. Photo: Suraj Mondal.

The Perils

The other causes for groundwater loss are changes in the landscape on account of infrastructure such as building basements, tunnels and metros, which disturb aquifers and recharge and discharge zones. Land subsidence causes damage to structures, making buildings unsafe, damaging linear infrastructure such as roads and railways, causing changes in elevation of streams and canals, which may cause them to breach their banks, flooding, and mine inundation. All of these lead to economic losses, and unnecessary loss of human life. Researchers believe that reversing land subsidence is not possible. The only way to arrest this deadly phenomenon is to manage groundwater extraction, and plan infrastructure carefully in a way that does not damage aquifers.

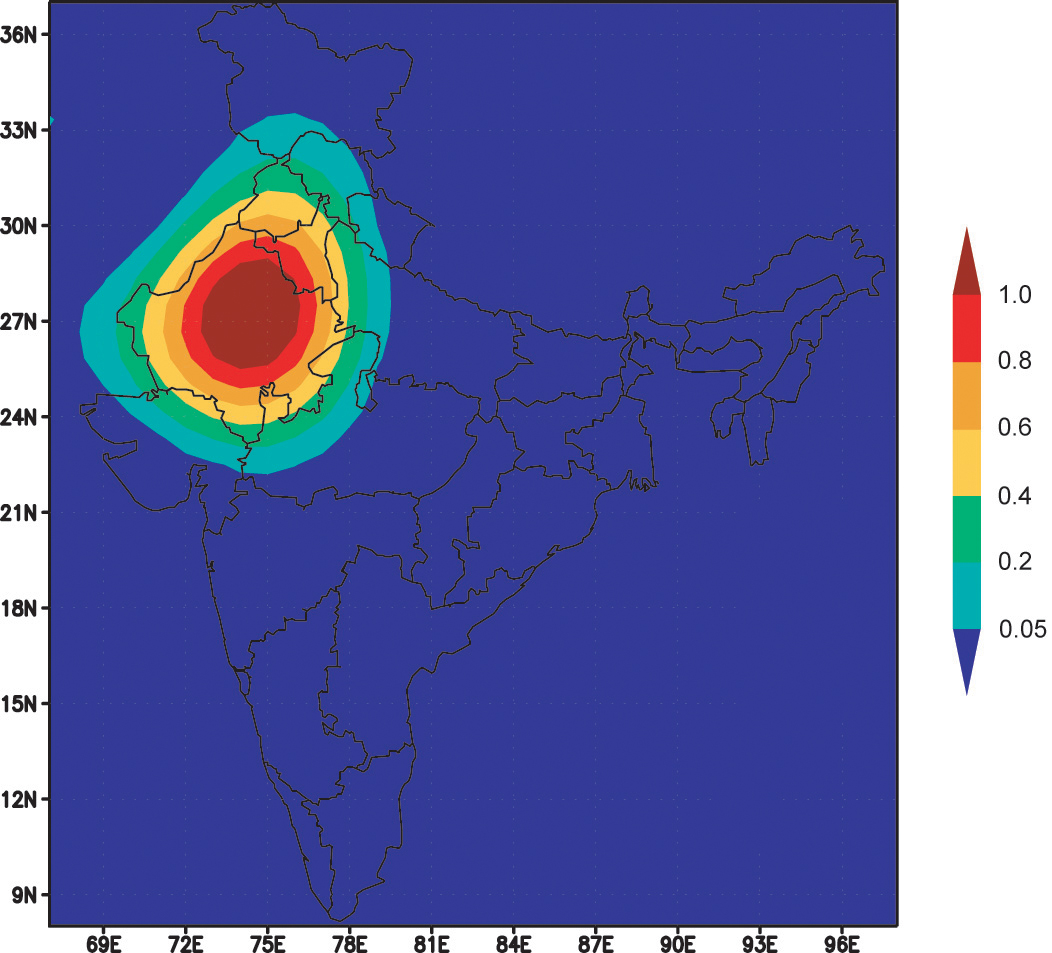

The warmer colours in the map of north India show greater sensitivity to groundwater storage changes. NASA found that 109 cubic km. of groundwater disappeared here from 2002 to 2008, at an average of one metre every three years, proving that the current rate of groundwater extraction is not sustainable. Photo: Public Domain/NASA/Matt Rodell.

What You Can Do

- Along with judicious water use, rainwater harvesting (RWH) alleviates some pressure from groundwater and piped dam water use. RWH was made mandatory in 2012 in Delhi, and according to the Model Building Bye Laws 2016, providing RWH systems is required for all residential plots above 100 sq. m. Check the status of RWH systems in your area, and get them implemented.

- The Advanced Centre for Water Resources Development and Management (ACWADAM) has mapped aquifers of Pune, which can be used to identify recharge and discharge zones to plan wells, infrastructure and building construction.

- CGWB also has a repository for groundwater management through their project National Project on Aquifer Management (NAQUIM), which one can use for planning.

- Report instances of illegal extraction of groundwater to the relevant authorities, such as the NGT, CGWB, or Pollution Control Boards.

- Talk to your neighbours, friends and family about the dire situation of land subsidence on account of groundwater extraction, to help manage precious underground resources much more effectively. Work toward initiating robust groundwater legislation to protect groundwater resources.

- Write a polite email or letter to Shri Gajendra Singh Shekhawat, Minister, Jal Shakti (minister-jalshakti@gov.in) and to the Central Ground Water Board (CGWB), Ministry of Jal Shakti, Department of Water Resources, Government of India (chmn-cgwb@nic.in) stating the following points:

- India is the largest user of groundwater, a fourth of the planet’s groundwater is withdrawn here.

- With the world’s largest population, and being the world’s largest user of groundwater, it is vital that we adopt sustainable and scientific management of our groundwater resources.

- This is vital to reduce the impacts of climate change-induced disasters that will have a cascading effect on our food security, economy and environment.

- State governments must be supported and encouraged to work with farmers to move away from water-guzzling crops.

- The contamination and pollution of our water resources must also be addressed effectively.

- We must strive to institute strong groundwater legislation to protect this vital resource.

_1691483644.png)