Birding By Sound

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 40

No. 10,

October 2020

By Pranad Patil

My day usually starts at around 4:30 a.m., when it is still quite dark outside. I live on the periphery of the Kanha Tiger Reserve in Madhya Pradesh, where I work as a naturalist with a wildlife lodge, and every so often I visit the park before daybreak. Though it is dark at this time of the day, it is not always quiet. Occasionally, there are chital alarm calls in the forested patches nearby, or the cackling sounds of geckos. However, with the onset of summer, more often than not I hear the unmistakable ‘brain-fever, brain-fever’ song of the Common Hawk-Cuckoo.

The call is sent out to attract a mate, or possibly as a territorial anouncement. Sounds made by birds (usually males) for these reasons are called ‘songs’, while sounds for other reasons are simply described as ‘calls’. Birders use the phrase (mnemonic) ‘brain-fever’ to describe this bird. And birders, wherever they go, in forests or rural India, are likely to hear the brain-fever bird, long before they actually see it. The loud, persistent three-note call emitted by the Common Hawk Cuckoo Hierococcyx varius, has been given the mnemonic ‘brain fever brain fever’ by the British who thought it sounded slightly ‘unhinged’. Photo: Pranad Patil.

The loud, persistent three-note call emitted by the Common Hawk Cuckoo Hierococcyx varius, has been given the mnemonic ‘brain fever brain fever’ by the British who thought it sounded slightly ‘unhinged’. Photo: Pranad Patil.

If I am not out on a morning safari, I tend to laze around in bed a touch longer. This allows another bird to disturb my sleep. The loud, whistling song of the Puff-throated Babbler, singing from the bushes outside my room, ensures I leave my bed in a somewhat foul mood. This bird’s song can be best remembered using the mnemonic ‘I hate you’. In my disgruntled demeanour caused by the bird’s call, I cannot help but reciprocate with my own ‘I hate you too’ calls (in my head, of course).

While mnemonics are useful to remember the songs of some birds and help in their identification, the strategy cannot be applied to all birds. Only about one-third of all songbirds broadcast just one type of song and assigning a phrase to remember them by is therefore quite easy. On the other end of the musical mastery scale, about 20 per cent of songbirds have more than five different types of songs in their repertoire. One bird that definitely fits in this category is the Oriental Magpie-Robin – another morning singer in the vicinity of my abode. The Oriental Magpie-Robin has a rich collection of sounds, with whistles, chirps, tweets, clucks, and even hisses combined to sing some complicated (and to me, somewhat randomly organised) symphonies. In an attempt to enrich its collection of notes, these robins often mimic other birds too. A male during the breeding season tries to impress a female with his richly embellished song, an indicator of his vigour.

While all Jungle Babblers Argya striata may sound similar to even the experienced birder, in reality, each individual has its own unique ‘voice’ – with individuals being able to recognise other members of its flock by its call! Photo:Pranad Patil.

While all Jungle Babblers Argya striata may sound similar to even the experienced birder, in reality, each individual has its own unique ‘voice’ – with individuals being able to recognise other members of its flock by its call! Photo:Pranad Patil.

Another beautiful songster, probably the best of the lot, is the White-rumped Shama in the forests of Kanha. A male shama has a melodious sound, and his calls include a wide variety of notes, some often learned while mimicking other birds. Studies suggest that in some birds, such as the robin and the shama, having a large repertoire of songs is a direct result of one gender being extremely choosy (usually the female) while selecting a mate. Studies have also shown that males that incorporate more sounds enjoy greater reproductive success. To be able to compete with rivals year after year, a bird must keep learning throughout its life. So birds such as robins and shamas (and even flycatchers and starlings) have the ability to learn, practice, perfect and incorporate new notes in their songs as long as they live. It is the human equivalent of learning a new language and speaking it fluently. Not such a ‘bird-brain’ after all!

The largest of the drongos and easily distinguishwable by their tails, flocks of Greater Racket-tailed Drongos Dicrurus paradiseus are known to be aggressive, often mobbing larger species in the nesting season. They are able to mimic bird calls and, surprisingly, even the croaking of frogs! Photo: Pranad Patil.

The largest of the drongos and easily distinguishwable by their tails, flocks of Greater Racket-tailed Drongos Dicrurus paradiseus are known to be aggressive, often mobbing larger species in the nesting season. They are able to mimic bird calls and, surprisingly, even the croaking of frogs! Photo: Pranad Patil.

Speaking of mnemonics, the ‘Did you do it?’ calls of the Red-wattled Lapwing are well-known to even amateur birdwatchers. But this familiar call made by the lapwing is not its song. This ground-dwelling bird takes to air when it perceives a threat to its offspring and dive bombs the unsuspecting predator, forcing the raider to take evasive action. This acrobatic action sequence is accompanied by its own theme music – the ‘Did you do it?’ calls. Such calls are better known as alarm calls.

Alarm calls are common among social birds, such as the often-encountered Jungle Babbler. These birds communicate vocally for a variety of reasons, including conveying danger. Members of a flock are in constant vocal touch with each other while foraging, preening, moving from one place to another, when the group gets separated, while mobbing at a threat, expressing distress and during virtually all other activity. Research has also shown that the acoustic features of the sound made by an individual Jungle Babbler are very different from those of another individual in the same flock. Simply put, one Jungle Babbler can recognise another by its sounds, quite the way we might recognise a friend by his or her voice while talking over the phone. But to our ears, all Jungle Babblers sound the same – harsh and abrasive. It is a marvel that these birds have been able to develop such complex vocal communication strategies – a language of their own, with several articulations to express themselves. I unfortunately get to experience the complexity of the Jungle Babbler’s vocalisations several times, as there is a flock that resides around my room. When the assemblage is determined to disturb my afternoon siesta with their harsh, nasal calls, I can only refer to this as a misfortune.

The term “mnemonics” is derived from an ancient Greek word mnÄ“monikos, which means “of memory”. In birding, mnemonic devices help you identify birds by their calls/songs. Mnemonic phrases string together the syllables and notes of a bird’s song so that you can remember its rhythm, pitch and tempo. When in a forest, more often than not, you will hear more birds than you manage to actually see, so by learning the art of mnemonics, you can “bird with the ear”! Here are some commonly used mnemonics by birders:

‘I will beat you’ and ‘I hate you’ – Puff-throated Babbler

‘Brain fever brain fever’ – Common Hawk Cuckoo

‘Pleased to meet you’ – Red-whiskered Bulbul

‘Daddy give me chocolate’ – Brown-cheeked Fulvetta

‘Crossword puzzle’ – Indian Cuckoo

‘That’s your choky pepper’ - Lesser Cuckoo

‘Twenty-twenty’ – Grey-headed Canary Flycatcher

‘Kapil Dev, Kapil Dev’ – Grey Francolin

‘Did he do it, did you do it’ – Red-wattled Lapwing

‘Peter Peter’ – Banded Bay Cuckoo

While scientists are close to understanding the complexity of bird calls in some species, there are other species where the mystery is far from being solved. For example, the Greater Racket-tailed Drongo, is frequently seen in mixed species flocks and is well-known for its ability to perfectly mimic the calls of the birds with which it interacts. Such mimicry is linked to sexual selection in some species. This is definitely not the case with the Greater Racket-tailed Drongo, as both genders can mimic and do so outside their breeding season too. What is fascinating about the drongo is that it seems to understand the meaning of a particular sound when it mimics it. For example, the drongo will mimic a Jungle Babbler’s alarm call when there is danger around and thus alert everyone. This is equivalent of us understanding the implication of a certain phrase in foreign language which we don’t know, and then using it in the correct context. Some parrots have been taught to do this with human speech in captivity, but this behaviour is unheard of in the wild. I have also seen Greater Racket-tailed Drongos imitate raptor calls, and then steal prey from other birds when the panic to locate the non-existing predator ensues. Whatever may be its reason to mimic other birds, the Great Racket-tailed Drongo is one amusing bird to witness when it puts on its best performance.

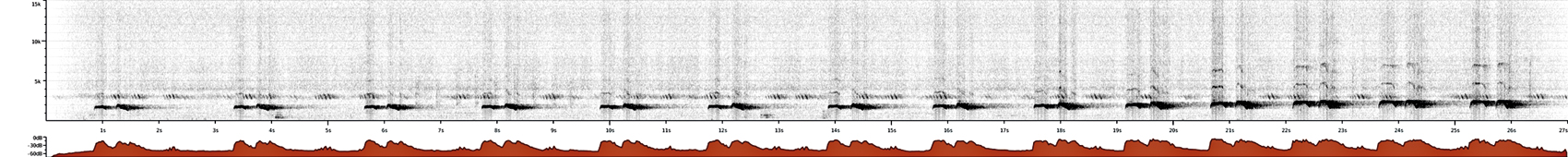

Sonogram: Red-wattled Lapwing

_1606719575.jpg)

Photo: Andrew Spencer/Public Domain

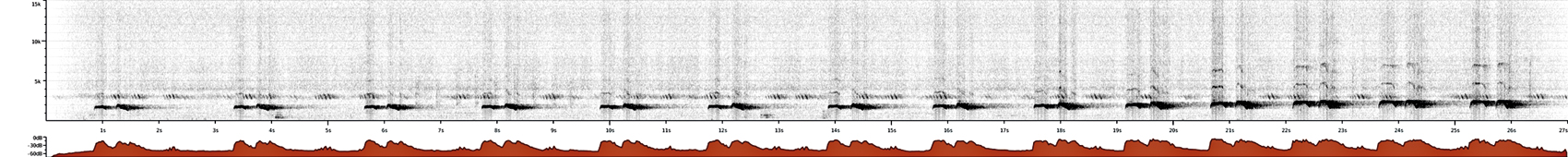

Sonogram: Common Hawk Cuckoo

Photo: David Farrow/Public Domain

Although there are birds all around us, it is easy to overlook bird sounds. However, if you pay just a little bit of attention, you will begin to notice birds in a whole new light. I get excited even when I hear owls hooting or nightjars churring. While it is difficult for me to pick one favourite birdcall, in the evening, I must confess I wait keenly for the Indian Cuckoo, whose calls can be easily remembered by memorising the mnemonic ‘one more bottle,’ and in the evening, it is a suggestion I choose not to ignore.

Kanha offers rewarding birdwatching experiences, with over 300 species, including a variety of passerines such as Puff-throated Babblers Pellorneum ruficeps, which usually prefer to forage in the leaf litter. Photo: Pranad Patil.

Kanha offers rewarding birdwatching experiences, with over 300 species, including a variety of passerines such as Puff-throated Babblers Pellorneum ruficeps, which usually prefer to forage in the leaf litter. Photo: Pranad Patil.

Pranad Patil is a naturalist by profession, currently working with a wildlife resort at the famous Kanha Tiger Reserve in Madhya Pradesh. He is also an amateur wildlife photographer and regularly writes about natural history for various magazines and blogs in an attempt to popularise the lesser known wildlife of our country.

_1606719575.jpg)