Brewing Biodiversity: The Secret of Truly Special Artisanal Coffee

First published on

January 18, 2024

By Sharmila Vaidyanathan

I realised how important coffee was long before I got a taste of it. A South Indian, I was acutely aware of how the entire household would wake every morning to embrace coffee’s aroma, how a strong cup of the beverage seemed to set the tone for the day. When guests arrived unexpectedly, the women of the house surreptitiously disappeared into the kitchen mid-conversation to check on the decoction. The conversational void would have to be tolerated till the filter had churned out enough coffee to come to everyone’s aid.

It feels like coffee has been among us forever, fueling us through life. But surprisingly, as historian A.R. Venkatachalapathy highlights in his book In Those Days There Was No Coffee: Writing on Cultural History, coffee became a household fixture in the south only sometime in the early 1900s. This is almost 300 years after coffee’s arrival in the country, concealed in the beard (though some references say strapped to the chest) of the Sufi monk Baba Budan, who came to India from Mocha, Yemen. He planted these seeds in Chikkamagaluru, Karnataka, and sparked India’s enduring love for the beverage.

Coffee initially fueled intellectual conversations among the elite in qahwahkhanas (coffee houses) of the Mughal Empire. Post 1840, it began to be cultivated extensively under British rule. For a while, coffee continued to hold a restricted audience in the country, being served in upscale clubs in Madras, Bangalore and Calcutta. Over the years, coffee’s charms proved hard to resist, and it made its way to the commoner’s cup.

Chai and kaapi may be rivals all over India, as favorite daily beverage, but in the South, filter kaapi reigns. Seen here: tumblers of South Indian filter coffee at Mavalli Tiffin Room, Bengaluru, in Karnataka. Photo: Charles Haynes/WikiCommons

Indian coffee houses are addas; places to socialise, hold discussions, meet friends—and drink a cuppa. Here, locals congregate at that Kolkata classic, Indian Coffee House, on College Street. Photo: Balaji Srinivasan/Shutterstock

Pankhuri Agrawal, through her food book club, Yayavr, encourages sociological, historical and anthropological analysis of various food-related topics, highlighting the many facets of food writing. She says that Venkatachalapathy’s work reveals Tamil culture’s initial resistance to coffee. ‘Coffee has had a tumultuous past. People were worried about the beverage replacing traditional alternatives such as fermented rice water or that women were drinking multiple cups a day!’ she adds.

Coffee farmers from the Western Ghats were among those who attended the 5th World Coffee Conference in Bengaluru, Karnataka, this September (top) – such as the Palani Hills’ Thadian Kudisai Coffee (event display, bottom). Organised by The International Coffee Organisation and India’s Coffee Board, the event looked for ways to attain ‘Sustainability through regenerative agriculture and circular economy’. Photos: Aditi Nagarajan/Thadian Kudisai

Now, coffee seems to have triumphed over these class, culture and gender barriers to become a movement of sorts. In FY 2022 alone, India consumed about 1.21 million bags of coffee, with each bag weighing 60 kilograms. India also exports its coffee to more than 50 countries. We are now entering the fourth wave of coffee, with continued focus on the science of brewing along with greater efforts to make specialty, high-quality coffee available to a larger audience.

Despite this growth, two significant obstacles lie in the path of coffee growing today—the loss of biodiversity and the ongoing climate crisis.

The fourth wave of coffee ‘is all about people—the producers and the roasters—and their experiments to create a complex coffee with layers of flavours’, Vogue India wrote, in a 2020 piece. And, about brewing specialty coffee at home. Seen here: drip brewing, filtered coffee, or pour-over is a method which involves pouring water over roasted, ground coffee beans contained in a filter. Photo: Alpha 7D/Shutterstock

More than Beans

Pranoy Thipaiah’s excited voice fills the other end of the phone as he talks about living, breathing and growing up with coffee. ‘The coffee movement in India is massive now. People are no longer just looking for a caffeine fix. We get calls from people who say things like, “Hey, I tried your coffee this morning, and I tasted pine nuts and maple syrup. Let me know what you are brewing next.” And that’s amazing.’

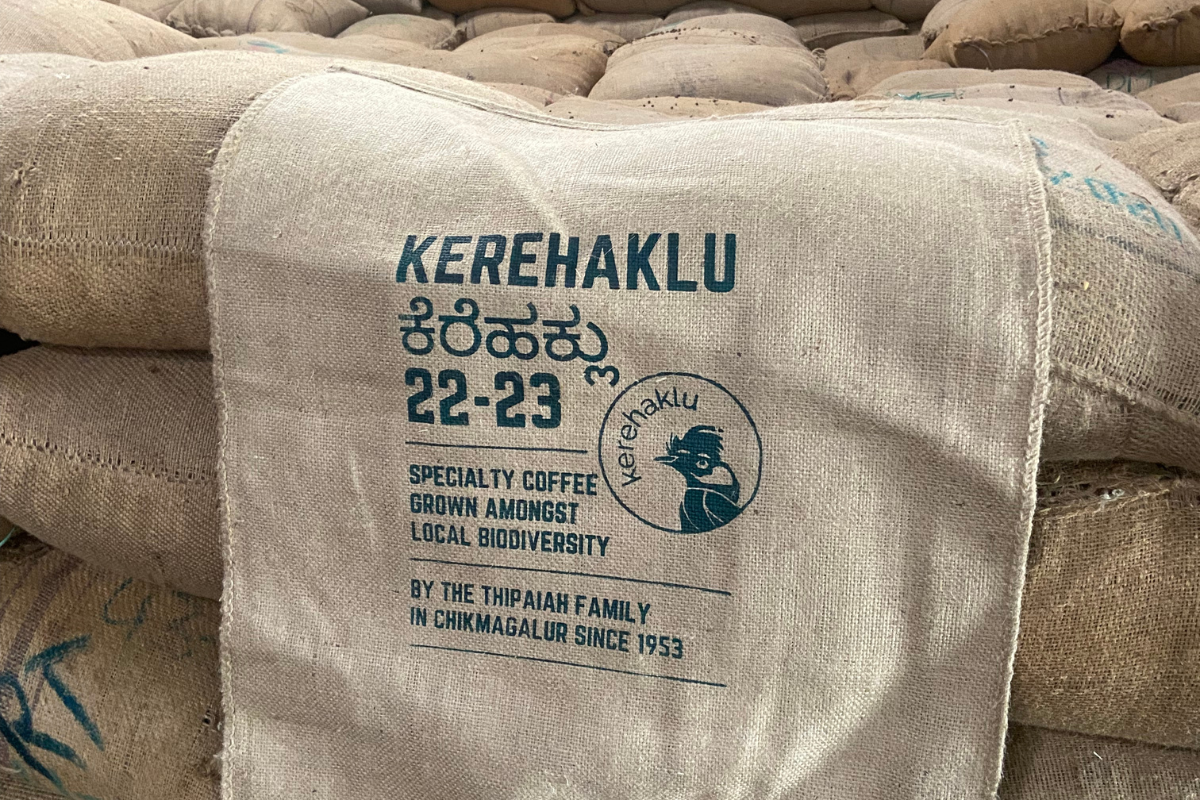

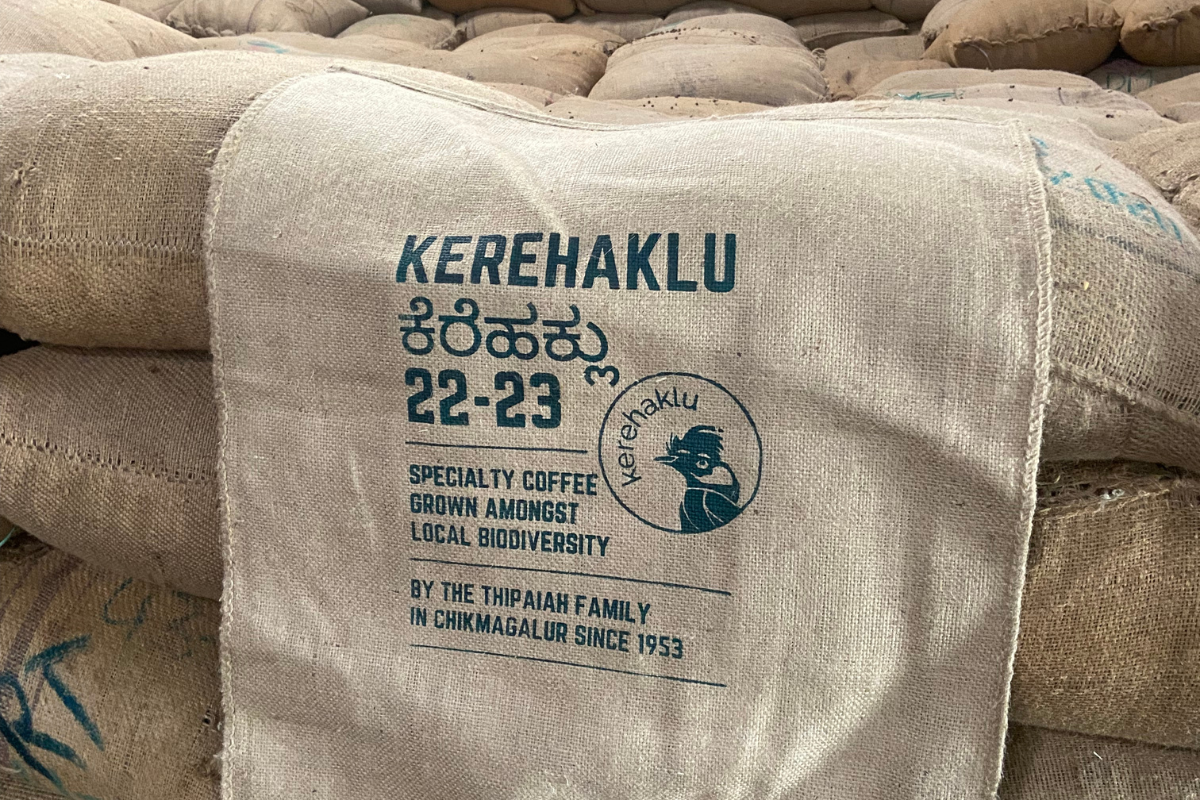

Thipaiah and his family run the Kerehaklu estate in Chikkamagaluru. Kerehaklu, or ‘the shelter by the lake’, sprawls across 250 acres, where the family cultivates specialty coffee that complements the local biodiversity. Along with coffee, they also grow avocados, pepper and a host of other seasonal fruits and vegetables while ensuring faunal and floral biodiversity in the estate. ‘Coffee has been in our family since 1953. So this is actually our 70th year,’ he says.

Pranoy Thipaiah studied biology in Sydney before he established Kerehaklu, a plantation and eco-retreat which produces coffee, 15 minutes away from Aldur, Karnataka. Between rounds of the estate (bottom), he meets with team members to package their coffee (top) and prepares his morning cuppa. Photos 1-2: Pranoy Thipaiah, 3: David Stallings

He talks about his estate, where Malabar giant squirrels hop from one treetop to another, about a splurge of colours in the canopy owing to the fruiting figs, about animals on the estate feeding on these fruits and how all these activities naturally nourish the soil. ‘The coffee plants growing around the fig trees are our healthiest blocks,’ he says. As Thipaiah paints this vivid panorama, he also distils the true essence of coffee cultivation: biodiversity.

A recent study published in the Annal of American Association of Geographers surveyed 344 coffee farm owners in Karnataka, noting that farmers who grow Arabica coffee support biodiversity by maintaining dense tree canopies required for these shade-grown varieties. These plantations can serve as ‘key conservation sites’ that support rich bird species diversity, as well as some mammalian diversity, it observed.

The Malabar giant squirrel is one of the Western Ghats’ poster children. It is one of four global species of giant squirrels, and is an indicator species, marking a biodiverse and healthy forest. While it is on the ‘least concern’ list of the IUCN, numbers are on the decline, say some wildlife experts. Photo: Abinaya Kalyanasundaram

When coffee was first cultivated in India, it was primarily grown in the shade of trees. Owing to the altitude and the temperatures, the Western Ghats in Karnataka, Kerala and Tamil Nadu provided the ideal environment for coffee cultivation. While these states are the traditional coffee growing regions, India also cultivates coffee in the north-east (Assam, Tripura, Manipur, Nagaland, Arunachal Pradesh and Meghalaya), Odisha, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana and Maharashtra, among a few other places.

The Blue-capped Rock Thrush (Monticola cinclorhyncha) is a migratory bird which winters in the Western Ghats, at home in the region’s shade-grown coffee estates. Look for it from November to March, when it travels over from Eastern Afghanistan, the Western and Central Himalayas, and Arunachal Pradesh. Photo: Rajkumar K.P.

In the Handbook of Climate Change and Biodiversity, NP Anil Kumar et al., from the MS Swaminathan Research Foundation, explain that post-1840, the British cleared large forest areas to propagate coffee cultivation. ‘The dominance of Arabica has been falling down for the last 20–25 years with the preference over the Robusta variety—a sturdy, high yielding and sun-loving species,’ they write, referring to the two main coffee varieties grown in the country. Over the years, an emphasis on intensified farming coupled with monocropping has changed both the way we produce coffee and the biodiversity of the Western Ghats, the researchers explain.

Variable rainfall has affected many coffee-growing areas in the Western Ghats. A study published in the International Journal of Environment, Agriculture and Biotechnology found that rainfall has decreased by 7.5 per cent over 33 years, from 1980 to 2014 in Kodagu or Coorg, Karnataka. Karnataka is the largest producer of coffee in India; over 60 per cent of the country’s coffee is grown in this state, most of it from the hills. Photo: Imagefoto55/Shutterstock

While coffee cultivation is often discussed as a driver of climate change, Kumar and his fellow scientists highlight that coffee grown in the shade of forest trees can sequester about 70–80 tonnes of carbon per hectare, aiding in climate change mitigation. Moreover, coffee agroforestry provides a haven for several endemic and endangered species.

PhD scholar and avid birder Karthika Chandran observed bird flocks in a shaded coffee plantation and a forest area in Wayanad for a study that identified 52 bird species in the plantation, of which nine were endemic. ‘These habitats, with a more complex structure from canopy to understory, provide several opportunities for birds to forage, nest and roost,’ she tells me.

Black Baza Coffee Company has been roasting a diverse range of coffees for the last seven years, working with smallholder farmers. High-altitude Arabicas are grown in the BR Hills (the Biligirirangana or Biligirirangan Hills) Tiger Reserve and the Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve, and mid- and low-elevation Robustas are grown by a collective in Wayanad as well as their only non-smallholder grower in Kodagu. Photo: Suraj Mahbubani

Between the Bean and the Cup

When Arshiya Bose first began interacting with smallholder coffee farmers in 2009 for her PhD research, she remembers writing down harvest seasons as a rule of thumb.‘ Arabica picking was December–January and Robusta was February–March; it was almost set in stone,’ she says. ‘I also don’t remember farmers discussing low yields, pests or other fungal diseases. These are not things that I wrote down in my notebook.’

The smallholder farmers of Black Baza work collaboratively to plan production. From top to bottom: Ramesha strikes a pose on his coffee farm, showing us the healthy leaves of his plants (images 1 and 2); a village meeting at Muthugadagadde Hamlet; a gathering of producers at Yerakanagadde Village. Photos: Vivek Muthuramalingam

Bose founded Black Baza Coffee in 2016, a grassroots organisation that works with 650 smallholder farmers across Karnataka, Tamil Nadu and Wayanad in Kerala), producing biodiversity-friendly coffee that also benefits the producers. She says that while certifications measure a few benchmarks, Black Baza works with coffee-growing communities using a participatory approach to look at larger conservation goals, including planting native trees, accounting for floral and faunal biodiversity and establishing ecological complexity.

But coffee cultivation is different from what it used to be when Bose began this journey. She explains that harvest seasons for the two coffee varieties have started to overlap on occasion due to changes in weather patterns, and pests and diseases are also frequent challenges, thereby impacting yields and the processing of the beans.

BR Hills offers biodiversity-friendly coffee from its part of south-western Karnataka, at its border with Tamil Nadu in South India. Located at the confluence of the Western and Eastern Ghats, this is a scenic area containing a wildlife sanctuary of around 539.52 sq. m., at an elevation of 1700 m. Photos: Yashas Chandra

Yahvi Mariwala, co-founder of Nandan Coffee Estate in Kodaikanal, agrees that along with the larger shifts, the changes around coffee’s immediate surroundings also have an impact on the crops. Spread over 35 acres, the Nandanvan Estate, where Nandan coffee is cultivated, has been one of the early adopters of biodynamic farming and has been practising organic cultivation for almost two decades. For Nandan’s ‘farm-to-cup’ coffee, they use harvested rainwater for processing and 100 per cent recyclable packaging for the final product. The coffee grows under the canopy of trees such as avocados, rosewood and jackfruit. Beyond coffee, Nandanvan provides a refuge for a host of animals such as elephants, bison, monkeys and more than 20 species of birds.

Three generations of coffee growers have produced specialty coffee on the Nandanvan Estate, which was created in 1994 and is located 10 km. south of Kodaikanal town in the Kodaikanal Wildlife Sanctuary. Nandanvan began to practice organic farming in 2004. Photo: Nandan Coffee

Mariwala shares that as much as their efforts are focused on ensuring a thriving ecosystem for coffee cultivation, they see the landscape around them slowly losing its green shade. She explains that many of the neighbouring estates are cutting down trees, paving the way for intensive agriculture and high-yielding crops such as beans. ‘Kodai is such a unique growing region, but when you see trees disappearing all around, it really makes you wonder what it means for the region as a whole,’ she says.

What Mariwala has observed of her immediate surroundings is a matter of growing concern. According to a 2015 study, between 1969 and 2011, Kodaikanal’s forest cover has decreased by more than 50 per cent as a result of anthropogenic activities. More recently, researchers noted that the Palani Hills (of which Kodaikanal is a part) has lost 66 per cent of its grasslands and 31 per cent of its shola forests between 1973 and 2014. Zoom out and you will find a similar picture unveiling across the Western Ghats.

Nandanvan’s coffee is grown beneath a canopy of orange, avocado, jackfruit, pepper, rosewood, teak and pine. Like many farms in this part of the Kodaikanal Wildlife Sanctuary, which spans over 700 sq. m., it sees a wide range of wildlife. Photos 1 and 2: Saffron Stays, Yahvi Mariwala

Various studies have highlighted the ripple effects of these anthropogenic activities in the region. In their summary of the 4X4 Climate Assessment Report, the South Asia Network on Dams, Rivers and People (SANDRP) summarised that the Western Ghats will most likely see the temperature increase to 26.8–27.5°C in the 2030s (the region’s average annual temperature is currently around 15°C). The report also states that the Ghats will see a decrease in the number of rainy days and an increase in the intensity of rain. These short, strong spells can have disastrous effects on coffee plants, and coffee growers are already facing the brunt of these changes.

Mariwala says that in 2022, the estate received a lot of unseasonal rainfall, and several crops were damaged during the harvest season. ‘Coffee cherries fell off the plants and started rotting before we could pick them.’ Nandanvan was not alone in its lament. According to the Karnataka Planters’ Association (KPA), coffee growers in the state faced losses of up to 35 per cent or more in November and December 2022 due to heavy rainfall.

Turning Over a New Leaf

Coffee growers are now finding new ways and means to protect our brews.

At Kerehaklu, Thipaiah is working on establishing structures where the harvested coffee can be protected during unseasonal conditions. ‘In December last year, we had monsoon-ish conditions for seven days, and having a parabola-like structure [for the beans] helped in preventing the coffee from rotting,’ he says, before adding, ‘That’s just for the coffee. There are other plants and animals as well on the estate, so we really need to invest in climate mitigation measures to protect the whole ecosystem.’ Recent reports also show farmers resorting to wood fire as a means to dry their coffee beans amidst unexpected rains.

Coffee cherries (on the branch, top) are spread out on surfaces to dry naturally, in the sun. They are raked and turned through the day, then covered at night or when it rains, taking up to several weeks to dry—till the moisture content of the cherries drops to 11 per cent, says the South India Coffee Company. Finally, they are roasted until they turn dark brown (bottom). Photo 1: Abinaya Kalyanasundaram, 2: Pranoy Thipaiah, 3: Yashas Chandra, 4: Vivek Muthuramalingam

What is interesting is that coffee growers are looking at both immediate solutions and long-term measures to safeguard coffee. At the South India Coffee Company (SICC), Kodagu, the team is exploring the benefits of ‘mara kaapi’ or excelsa coffee. ‘Excelsa is a deep-rooted coffee plant that has lower transpiration losses than Robusta. This makes Excelsa more drought-tolerant and pest-resistant. We are also evaluating specific varieties of Excelsa that have high cup quality and yield potential,’ explains Akshay Dashrath, co-founder and grower at SICC.

Dashrath adds that SICC’s long-term goals include researching native coffee species such as Coffea wightiana, Coffea benghalensis and Coffea travancorensis. ‘These species have the potential to be used as rootstocks or as auxiliary income for growers. We are also exploring other coffee species, such as racemosa, that have hardy roots and could be used to reduce the water requirements of Robusta coffee plants,’ he says. Kerehaklu is also getting people to familiarise themselves with mara kaapi and is building awareness about the variety.

While finding resilient varieties is essential, it is not a solution in itself and cannot allow us to become complacent about climate change mitigation, explains team Black Baza in a recent social media post. Its initiatives include building processes centred around coffee growers, paying attention to traditional ecological knowledge and building awareness of biodiversity concerns in consumers. Grassroots action ensures a long-term vision for sustainability—’one in which biodiversity, local ecosystems and peoples’ well-beings are at the heart’. Team Black Baza has termed this the 1,000-Year Brew and hopes that it will encourage sustained action to promote biodiverse coffee.

Priyanka Nagarajan, a coffee taster living in the Palani Hills, best summarises the efforts of the coffee community. ‘As the soil becomes enriched as a result of the floral and faunal biodiversity, the coffee plant and all the forces it works with create a diverse palate of compounds that are stored in the coffee bean. When roasted and brewed, this translates to complex flavours in your cup of coffee. The intense aroma and lingering aftertaste are signs of a biodiverse ecosystem.’ Now that’s a cup we could all wake up to.

This story first appeared in The Kodai Chronicle: A Dispatch from the Western Ghats.