Dilip D. Khatau - 1942-2023

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 43

No. 6,

June 2023

Conservationist. Industrialist. Chairman, The Corbett Foundation.

By Bittu Sahgal

I knew he would be a dear friend from the very first time we met at the Bombay Gymkhana, shortly after the launch of Sanctuary Asia magazine in October 1981. The inaugural Sanctuary issue in hand, he flipped through its pages for a good five minutes, as I sat quietly sipping a cup of coffee, waiting like an expectant father to hear his verdict. And then, I heard him say: “I have lived and loved wild places and wildlife all my life, and India badly needed a magazine of this quality and simple, credible content. Now tell me, how can I help you with its long-term survival?”

Dilip Khatau, seen here receiving the Gallery of Legends, East India Travel Award in 2017, was just as passionate about the fecund forests of Kumaon and Garhwal as he was about the arid grasslands of Kutchh. Photo Courtesy: Rina Khatau.

That was my friend Dilip Khatau, shikari-turned-conservationist, who passed away earlier this year on March 9, 2023 in Mumbai. I cannot mourn his passing, because he lived every day of his life to the lees, displaying little regret and even less dismay at the disappointments that targeted us each day. Ever smiling, ever helpful, and totally in love with nature, Dilip immediately bought a bunch of Sanctuary subscriptions to present to people who, he said, “badly needed to be educated!”. He went on to suggest several names of people including ‘Bapa’ R.S. Dharmakumarsinhji, Divyabhanusinh Chavda and M.K. Ranjitsinh, who he said would offer Sanctuary real perspectives on conservation. All three eventually helped shape the editorial stance of the magazine.

Sitting at the Bombay Gymkhana soon after he launched The Corbett Foundation on Earth Day, April 22, 1994, we got talking, and he listened patiently as I rued the fact that India was losing forests, wetlands, mangroves and more. He responded in his usual soft voice: “Of course you are right! But you must visit Banni in Kutchh, which is one of Asia’s largest grassland ecosystems, to realise that grasslands are actually India’s fastest vanishing ecosystems… because we imagine they are wastelands, where food should instead be grown.”

He was right. Banni once extended to around 4,000 sq. km. Possibly under half that area now exists to any degree of health. To the horror of those who understood the value of grasslands, helicopters were actually used by over-enthusiastic, but ignorant, policy makers (under the tutelage of the World Bank and OECF) to broadcast exotic Prosopis juliflora (mesquite) seeds, which quickly spread out of control and took over the entire grassland. Dr. Asad Rahmani endorsed Dilip’s concerns, and the three of us spoke about the need to protect vital habitats such as Nalia, where the Air Force Base ended up protecting vanishing wildlife species including the Great Indian Bustard.

Many years later, when I visited Banni, I saw for myself just how right Dilip was. Over half of this austere, yet hugely productive ecosystem had been taken over by Prosopis, which proved to be so difficult to eradicate that the locals referred to it as ganda babul – the mad tree. And yet, when I last met Dilip, he said to me: “We must convince the government to protect the grasslands of Kutchh to save Lesser Floricans and Houbara Bustards, and also to nurture the habitat and keep it ready to receive the captive-bred Great Indian Bustards, that the Wildlife Institute of India is carefully raising.”

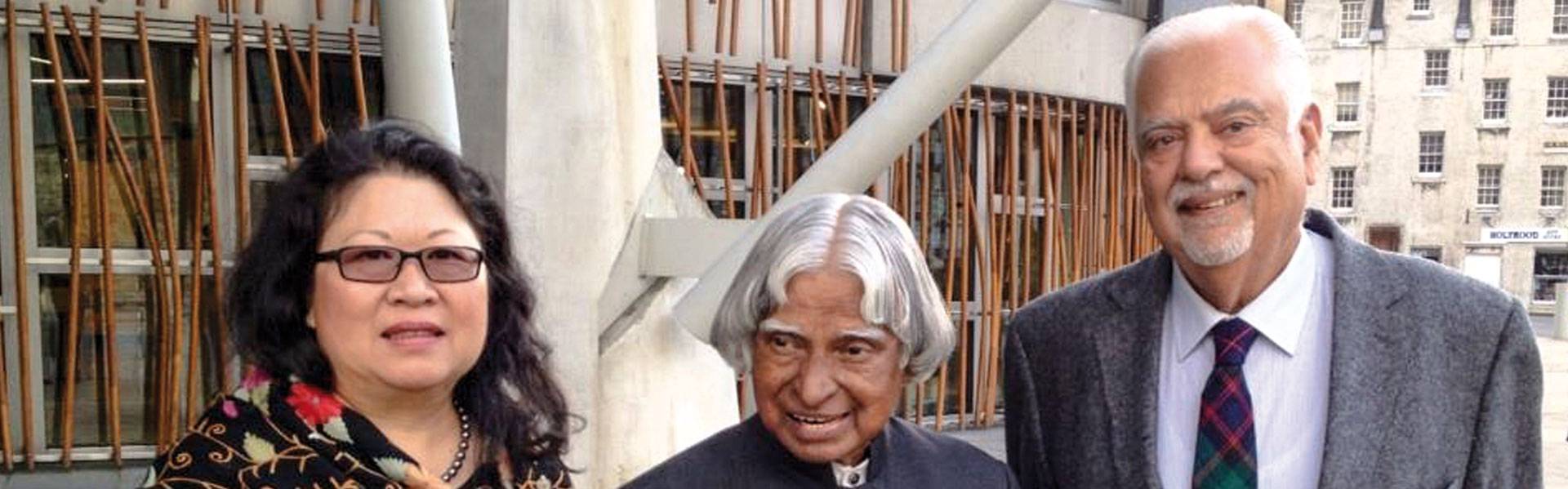

Dilip Khatau and his wife Rina Khatau with India’s 11th President Dr. A.P.J. Abdul Kalam. Photo Courtesy: Rina Khatau.

Dilip exuded pride in Kutchh, its people and its exquisite wildlife diversity. In his words: “There is another aspect of Kutchh that makes it a favoured destination for naturalists. It is one of the best places in the world to watch birds. The area was fortunate to have a succession of rulers who were bird-lovers, and this fascination is reflected in the art and culture of the region, which was also once known for its falconry.”

To the end of his days, Dilip would advocate passionately for the need to protect the less spoken about wildlife of Kutchh including wolves, hyaenas, caracals and chinkara, blackbuck, blue bulls and wild pigs, plus an incredible diversity of avians including raptors. He was equally committed to wildlife conservation throughout the country and often said, “I want the forests of Kumaon and Garhwal to reverberate with the roar of tigers long after I have passed on. This is the raison d’etre of The Corbett Foundation.”

The Corbett Foundation’s Director Kedar Gore, who worked closely with Khatau, is devastated by his passing, but is committed to staying true to his legacy. “India has lost one of the greatest philanthropists, industrialists and wildlife lovers. Mr. Khatau loved tigers, Great Indian Bustards and myriad other species, and did everything in his capacity for wilderness conservation. I have been fortunate to spend 14 years in The Corbett Foundation, which he founded for the harmonious coexistence of humans and wildlife,” Gore wrote.

Islands of Diversity

Islands of Diversity

If you were to examine a map carefully, you would see that Kutchh is geographically well-defined by its physical boundaries. To the north and east lie the Great and Little Rann of Kutchh, to the west are the productive tidal marshes and creeks that are the nurseries of the Arabian Sea, and to the south is the Gulf of Kutchh itself. Though it might look one-dimensional, ecologically speaking, Kutchh boasts a number of diverse ecosystem types in close proximity to each other: the coral reefs, mangroves and beaches of the Arabian Sea and the Gulf of Kutchh, the vast grasslands of Banni, the marshes of Dhand and of course, the salt deserts of the Great Rann. While people everywhere talk of the fragility of the rainforests, few truly understand how vital deserts are to our biodiversity, or how fragile. All species here hold on to survival by exceedingly tentative threads and the slightest trauma can trigger a wave of extinctions, almost before anyone might consider rallying to prevent them.

Consider, for instance, just one very vital aspect of the Rann – its many

bets or high grounds that turn into islands when the sea water is carried north by winds and tides. In both the Little and Great Rann, the

bets are the only forage available to herbivores such as chinkara, blackbuck and wild asses. But in recent years the human invasion of these green ‘life rafts’ of survival has risen manifold.

Salt workers come here for fuelwood, graziers invade the

bets with thousands of livestock and of late, hordes of tourists have taken to driving ‘off the road’ through the delicate

bets... just for fun. Rather than come down hard on such intrusions, both Dr. [Asad] Rahmani and I feel that there is tremendous scope to educate all those who impact the Rann and Kutchh itself, because their traditions have instilled in them a deep and abiding respect for nature.

Excerpt from Kutchh, an Arid Wonderland by Dilip Khatau, Sanctuary Vol. XX No. 3, May/June 2000.Dilip’s wife Rina has decided to personally head The Corbett Foundation, Dilip’s first love. Both always spoke with admiration of the local communities, whose cultures were birthed by the arid grasslands of Kutchh along the southern aspect of the Thar Desert. Rina, who I met just a month ago, reiterates that Dilip’s life requires to be celebrated, not mourned. She unequivocally said that India should take a cue from Africa and recognise that grassland protection will result in species diversity and large, sustainable tourism inflows on a scale that could give local communities the respect they deserve, so that we can usher in a new age of sustainable economic growth in a landscape that, just a few decades ago, was considered wasteland.