Dr. Jane Goodall: A Symbol Of Hope

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 41

No. 12,

December 2021

By Lakshmy Raman

“Surely, we do not want to live in a world without the great apes, our closest living relatives in the animal kingdom? A world where we can no longer marvel at the magnificent flight of Bald Eagles or hear the howl of wolves under the moon? A world not enhanced by the sight of a grizzly bear and her cubs hunting for berries in the wilderness? What would our grandchildren think if these magical images were only to be found in books?”

— Dr. Jane Goodall’s Statement in Defense Of The Endangered Species Act.

Nearly 62 years ago, a young woman made her first visit to the Gombe Stream National Park, Tanzania. She had been sent on an assignment to observe chimpanzees by the legendary paleo-anthropologist Dr. Louis Leakey. She had no academic credentials or relevant field experience. All she had was an unrelenting passion to be a naturalist, an innate compassion for animals and the willingness to dedicate her life to them.

One day, as she walked through the rainforest of Gombe, western Tanzania, she observed a large, male chimpanzee at a distance, foraging for food. Peering through her binoculars, she watched in amazement as he bent a twig, stripped it off its leaves and pushed it into a termite mound and then using it as a tool, began to spoon the insects into his mouth.

Jane knew she was witnessing something incredible but even she could not have imagined how involved her life would become with the amazing apes whose lives she was studying. Little was known of chimpanzees then and to document what was the first instance of a non-human making and using a tool was truly trailblazing. She would go on to transform the way the world viewed species behaviour and conservation. And her story, though undeniably about scientific observations of chimpanzees, also became the story of the collective power of individual action.

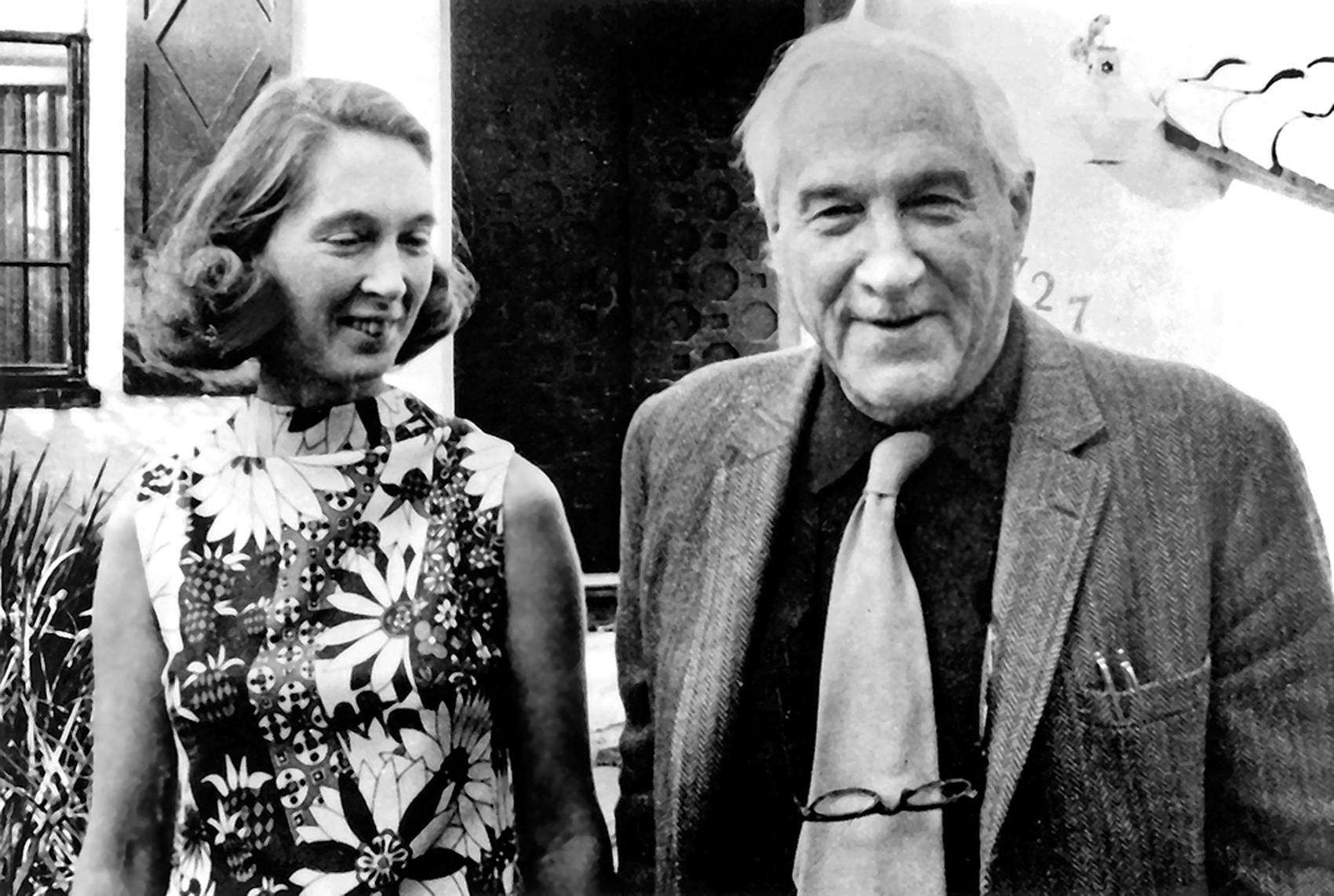

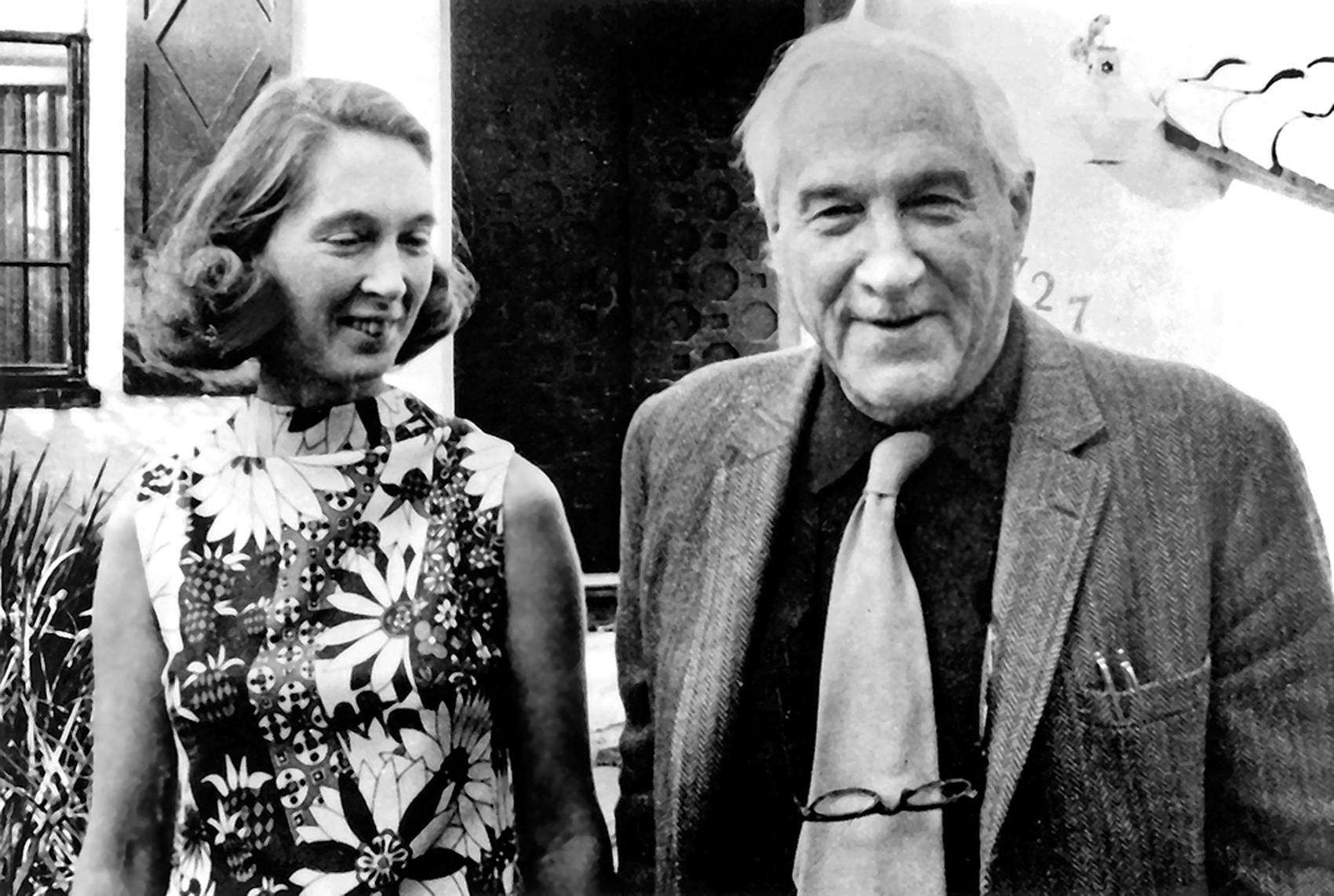

Jane Goodall with Dr. Louis Leakey, a legendary paleo-anthropologist, who offered her the opportunity to begin a study of chimpanzees on the edge of Lake Tanganyika, Tanzania. He was impressed with her natural history knowledge and passion to understand animals and believed her non-academic background would provide a fresh perspective. Photo:The Jane Goodall Institute

Jane Goodall with Dr. Louis Leakey, a legendary paleo-anthropologist, who offered her the opportunity to begin a study of chimpanzees on the edge of Lake Tanganyika, Tanzania. He was impressed with her natural history knowledge and passion to understand animals and believed her non-academic background would provide a fresh perspective. Photo:The Jane Goodall Institute

Early Years

Born on April 3, 1934 in London, England, Valerie Jane Morris-Goodall adored animals as a child. When she was just a year old, she was given a stuffed toy chimpanzee that she named Jubilee and carried with her everywhere (the scruffy toy continues to have a place in her home even now). Curious about the natural world, she watched a hen lay eggs for hours. In all her adventures, she had a delightful companion in Rusty, a black mongrel from her neighbourhood. At 11, she founded the ‘Alligator Society’ and expected members to be able to recognise at least 10 birds, 10 dogs, 10 trees and five butterflies or moths.

Jane Goodall was fascinated by Africa and desperate to learn all she could about animals. She read as many books as she could from the library about Africa and its wildlife and dreamt of living there. After completing her schooling, her family was unable to pay college tuition fees. She trained to be a secretary and worked at Oxford University and later at a London filmmaking company. An invitation from a school friend to her family’s farm in Kenya in 1956 gave Jane her opportunity. So, she worked as a waitress and saved the fare to travel to Kenya by boat. There she met Dr. Leakey, then a curator at the Coryndon Museum in Nairobi, who hired her as his assistant after being impressed by her knowledge of natural history and later offered her a chance to participate in an expedition to Olduvai Gorge where he was searching for artifacts linked to early humans. Goodall recalls the experience as being magical and after a day’s work was able to observe the wildlife there. Dr. Leakey was keen for someone to study wild chimpanzees on the edge of Lake Tanganyika and offered Jane Goodall the opportunity to travel there. Three years later, and accompanied by her mother, Jane began her research at the Gombe Stream Chimpanzee Reserve. The rest, as they say, was history. This was what Jane had hoped for all her life and there was no looking back.

In her early days at Gombe, equipped with just a notebook, binoculars and telescope, Jane Goodall spent hours, searching for and observing chimpanzees. It took several weeks to get the apes to accept her presence and not run away. Photo:The Jane Goodall Institute

In her early days at Gombe, equipped with just a notebook, binoculars and telescope, Jane Goodall spent hours, searching for and observing chimpanzees. It took several weeks to get the apes to accept her presence and not run away. Photo:The Jane Goodall Institute

She approached her research in Gombe, Tanzania, with no preconceived notions about her subjects. In doing so, she created a new standard for the study of these chimpanzees in the wild and in the process made discoveries that seemed impossible to the scientific world. When advised of her observation of chimpanzees making and using tools, her mentor Louis Leakey said, “Now we must redefine ‘tool’, redefine ‘man’, or accept chimpanzees as humans”.

It was not an easy trip. When Goodall was in Gombe, the Belgian Congo had just entered into a civil war. Her initial stay was in an old army tent. It took several weeks to get the chimps to accept her presence and not run away. One of the first to accept her approach was a male, whom she named David Greybeard for his grey tufted chin. He was also the same chimp she first recorded making and using the twig as a tool to fish for termites.

When Dr. Leakey arranged for her to attend Cambridge University, her methods of research were not accepted by other scientists who did not approve of her approach such as giving the chimpanzees names. However, for Jane Goodall, ethology did not have to be a hard science and she believed firmly that animals, like humans, do have personalities and feelings. She says that while her colleagues insisted that she shouldn’t talk about chimps having emotions and personalities, she knew even as a child playing with her dog, Rusty, that they are intelligent and share a lot of emotions that we consider unique to humans.

Jane Goodall was only 26 years old when she travelled from England to Tanzania, and into the world of wild chimpanzees. Since then, over nearly six decades, she has redefined species behaviour and helped us understand fascinating aspects of our closest living relatives. Photo:The Jane Goodall Institute/Bill Wallauer

Jane Goodall was only 26 years old when she travelled from England to Tanzania, and into the world of wild chimpanzees. Since then, over nearly six decades, she has redefined species behaviour and helped us understand fascinating aspects of our closest living relatives. Photo:The Jane Goodall Institute/Bill Wallauer

Student, Protector, Historian

Goodall went on to get her doctorate in 1965 and continued to spend the next few decades researching the families of wild chimpanzees in Gombe. Apart from making and using tools, she also recorded their interactions with each other, watching them embracing, patting and kissing each other and witnessed their family interactions. She also found that they had strong mother-infant bonds, experience adolescence, express compassion, fight brutally – even killing members of their own species and that they could be wily in their actions to achieve their needs. She also discovered that they were omnivorous, hunting and eating not only insects but also bush pigs, colobus monkeys and other small mammals.

In her 1971 book, In the Shadow of Man, she wrote of David Greybeard expressing trust in her one day as she offered a ripe red palm nut lying on the ground. “When I moved my hand closer, he looked at it, and then at me, and then he took the fruit, and at the same time held my hand firmly and gently with his own. As I sat motionless, he released my hand, looked down at the nut, and dropped it to the ground. At that moment, there was no need of any scientific knowledge to understand his communication of reassurance. The soft pressure of his fingers spoke to me not through my intellect but through a more primitive emotional channel: the barrier of untold centuries which has grown up during the separate evolution of man and chimpanzee was, for those few seconds, broken down.”

In 1977, she founded the Jane Goodall Institute to continue her research and to advance the protection and conservation of wild chimpanzees and improve the lives of those in captivity. There are now 24 JGI offices around the world and one of the latest is the Jane Goodall Institute - India. In 1991, she started her global humanitarian and environmental programme Jane Goodall’s Roots & Shoots to empower young people of all ages to become involved in hands-on projects of their choosing to benefit the community, animals (including domestic animals) and the environment we all share. There are growing programmes of Roots & Shoots in India led by Executive Director Shweta Khare Naik who has extensive knowledge of the programme, having lived in Tanzania where Roots & Shoots first began three decades ago.

Dr. Jane Goodall with Roots & Shoots members in Salzburg, Austria. This global humanitarian and environmental programme was started by Jane in 1991 to empower young people to become involved in hands-on projects to benefit the community, animals and the environment. Photo: Robert Ratzer

The Jane Goodall Institute

Dr. Jane Goodall with Roots & Shoots members in Salzburg, Austria. This global humanitarian and environmental programme was started by Jane in 1991 to empower young people to become involved in hands-on projects to benefit the community, animals and the environment. Photo: Robert Ratzer

The Jane Goodall Institute

Since its establishment in 1977, JGI has focused on various ways in which it can support chimpanzee conservation, keeping science at the core of its work. The Tchimpounga Chimpanzee Rehabilitation Centre in the Republic of Congo was created to care for chimps orphaned by the illegal bushmeat and pet trades. In South Africa, the Chimp Eden Sanctuary cares for chimpanzees rescued from unhappy circumstances in assorted African countries. The Lake Tanganyika Catchment Reforestation and Education (Tacare) community centred conservation programme in western Tanzania was created to support sustainable livelihoods in villages around Lake Tanganyika while stemming the degradation of natural resources in the area and is now replicated in five other African countries.

Meanwhile, JGI’s conservation science programmes are focused on working toward science-based management solutions for conservation of chimpanzees and their habitats. From publishing hundreds of scientific papers and theses based on research at the Gombe Stream Research Centre to encouraging local girl students to return to school, providing scholarships to young women for their education and training locals in forest monitoring technology, JGI has been committed to truly make a difference. JGI’s conservation science vision focusses on exploring, innovating and uncovering solutions, cutting edge geospatial technologies and tools to protect the wilderness and wildlife. It also relies on citizen science and crowdsourcing to engage and empower local communities, thus working to expand Jane Goodall’s vision into a global mission to build a better tomorrow.

In the 1900s, there were more than a million wild chimpanzees across their range in Africa. Today, there are only around 340,000, and wild chimpanzees are highly endangered. This is caused by loss of habitat, poaching, logging and the bushmeat trade. Jane Goodall, who continues to be a tireless advocate for conservation, animal rights and climate change expressed her dismay in a 2020 interview with ABC News, that big business continues to be reluctant to change the way they operate. “We brought this pandemic to a large extent on ourselves – we have disrespected the natural world, we disrespected animals, and we’ve been cutting down forests. Animals are being driven in closer contact with people. Animals are being hunted, killed and eaten. They’re being trafficked,” she said, adding, “If we don’t get together soon and start respecting the natural world and realising we’re a part of it… then it’s going to be a very, very, very bleak look for our great-great grandchildren.”

Dr. Goodall has visited India on several occasions in the past few years and looks forward to a time when she can return to witness the growth of Roots & Shoots here. She is delighted that the Sanctuary Nature Foundation has offered to work with Shweta Khare Naik and the Jane Goodall Institute India to help develop the Roots & Shoots programme in the country.

Author of many books for both adults and children, Dr. Jane Goodall’s latest book is The Book of Hope. Recipient of many awards and featured in countless films and documentaries, Dr. Goodall is currently working virtually from her family home in Bournemouth in the U.K.