Eastern Himalayan Rural Futures

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 40

No. 4,

April 2020

By Joanna Dawson, Ranjit Barthakur and Saurav Malhotra

It was early in 2016, when we first found ourselves in a young, green forest in the tiny town of Bhairabkunda, in the heart of elephant country in Udalguri district, Assam. Years of insurgency had stripped the area of its forests, however, leaving the elephants that once roamed this land with nowhere to go. Not surprisingly, in recent years, human elephant conflict has ravaged the nearby villages.

We were lucky to even have this young forest. Since 2005, 35 men and women of a programme under the government’s Joint Forest Management Committee (JFMC) planted 750 acres, on their own initiative. Their efforts were a tiny drop in a bucket: human-elephant conflict was on the rise and the area still desperately needed habitat corridors for elephants to move freely without invading human settlements.

On paper, we had the perfect solution. With their help and the support of communities around the area, we would be able to restore habitats at a scale that would allow free movement for the elephants that once ruled this landscape. We would do this by going straight to the heart of the problem: the communities that had cleared the forests over the years.

We soon discovered that tackling a problem as complicated as this at its root cause raised a hundred other questions. The broader community had plenty of other concerns – with more elephants passing through, were they meant to accept a state of perpetual risk for their crops and homes? Wouldn’t this land be put to better use as a pasture? What about agriculture? How was this going to benefit them?

A year later, we faced the same questions in a tiny village on the fringes of the Balipara Reserve Forest. In Bhairabkunda, the JFMC had spent years changing minds. They had negotiated negligence, scepticism and even spiteful destruction: parts of the forests were burned to demonstrate opposition to the whole idea. Years of persuasion had brought their neighbours around to the idea of a new forest in their backyard.

At Bogijulee, surrounded by the wasteland remains of what once was a lush green forest, we went back to the basics as we tried to answer two simple, recurring questions: Why forests? Why not people?

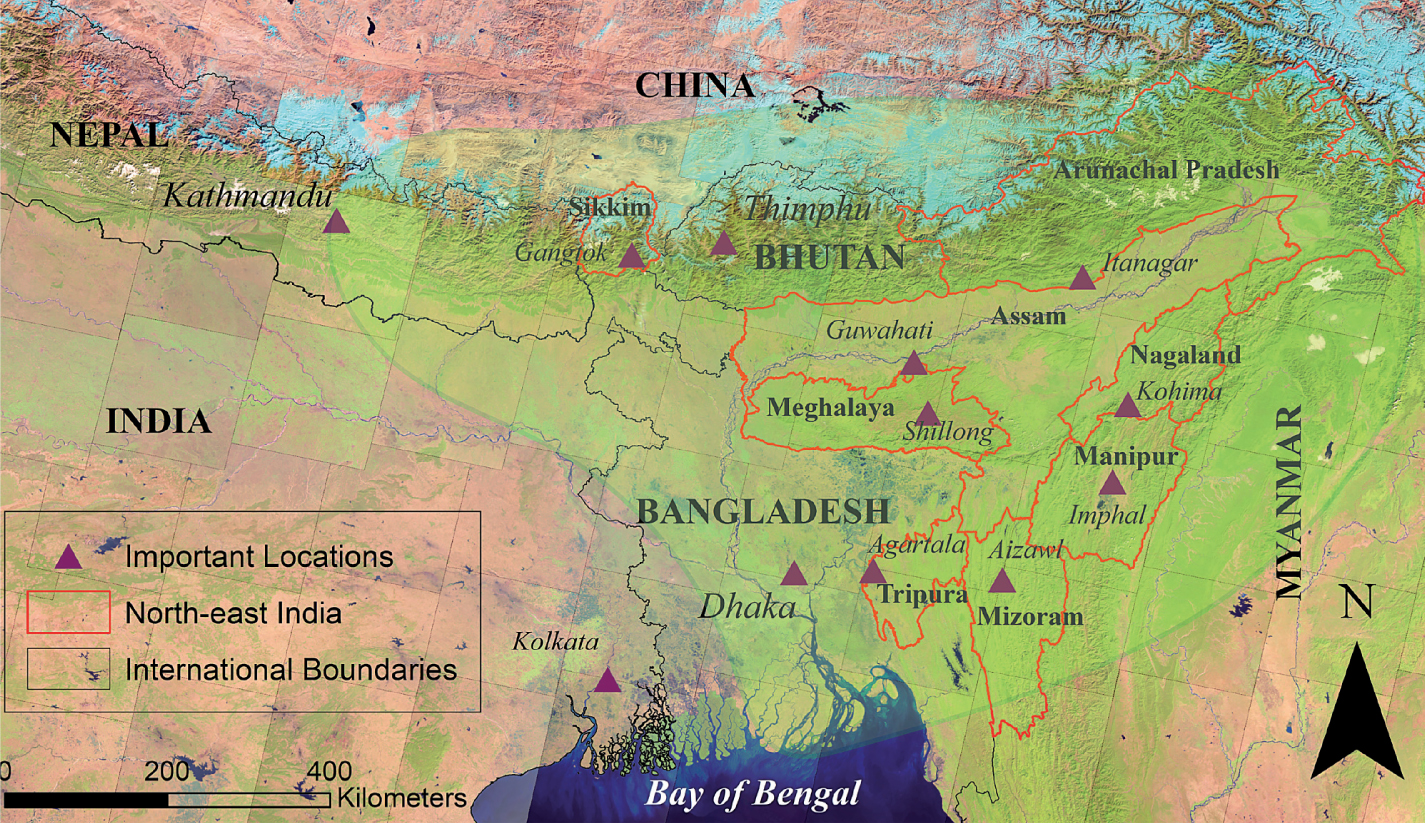

THE EASTERN HIMALAYA – FROM SNOWLINE TO SEALINE

For representation only. Map not to scale. Borders neither authenticated nor verified.

Stretching all the way from Eastern Nepal to Yunnan in China, the Eastern Himalaya encompasses Bhutan, the Northeastern states and the North Bengal hills in India, Bangladesh, South Eastern Tibet, and parts of northern Myanmar. Of the four global biodiversity hotspots present in India, it is home to two of the richest biodiversity hotspots – the Indo-Burma hotspot and the Eastern Himalaya hotspot. In the east, the mountains of Southwest China constitute a third biodiversity hotspot.

Spanning snowline to sealine, it features habitats as diverse as the coniferous forests of Bhutan, grasslands in Nepal, the dense subtropical forests of Meghalaya, the swampland forests and mangroves of Bangladesh’s Sundarbans, freshwater habitats along the Brahmaputra river and alpine shrubland, meadows and montane ecosystems in the mountains of Arunachal Pradesh and southwestern China. The region is also a lifeline for Asia: its biggest rivers – the Yangtze, Ganges, Brahmaputra, Indus and

Mekong – all find their sources in these mountains, supplying water to billions.

The biodiversity of the Eastern Himalaya is as unique and as wide-ranging as its ecoregions, nurturing over 10,000 plant species, 300 mammals, and over 900 species of birds. Several of these are endemic to the region, and new species are still being discovered every year: nearly 200 were discovered between 2009 and 2014 alone. In addition to iconic charismatic species such as the Asian elephant and the one-horned rhino, the Eastern Himalaya is also home to highly endangered species such as the pygmy hog, Bengal Florican, hispid hare, golden langur, river dolphin, Rufous-necked Hornbill and snow leopard – among many others.

In the mountainous tea estates of Udalguri, Assam, the inevitable passage of elephants through farms and tea estates results in conflicts throughout the year. Photo: Niraj Mani Chourasia

NATURE NEEDS HALF NEEDS THE EASTERN HIMALAYA

With a quarter of its ecosystems completely intact, the Eastern Himalaya is a landmark for conservation efforts globally. Around 60 per cent of the region is still under forest cover and within India, the Eastern Himalaya represents over three quarters of its intact forest cover. It spans 99 Protected Areas, including iconic world heritage sites such as the Kaziranga and the Sundarbans – though only 15 per cent of its total area is Protected Area.

The region represents one of many test cases in how the 'Nature Needs Half' goal of turning half the earth over to nature can be met, while protecting indigenous community interests in the area. The Eastern Himalaya is culturally rich and diverse, with over 200 distinct ethnic groups and 40 different spoken languages, representing all the major religions of the world – in addition to a myriad indigenous faiths and practices. Many of these landscapes are spiritually significant to these communities and protecting them is deeply interwoven in their cultural fabric. Sacred groves dot the region, allowing unique biodiversity to thrive untouched. Sacred peaks such as Khangchendzonga in Sikkim and Jomolhari in Bhutan are now Protected Areas, recognised as vitally important conservation zones because of the pristine and well-preserved nature of their ecosystems – tended to by the indigenous communities living within them.

Special protections under the constitution in India grant communities relative autonomy and control over traditional lands: over two-thirds of forests within the region. Within these forests, communities often have designated conservation zones, whether in the form of sacred groves, community-managed forests or community conservation areas. Despite the rich mineral, coal and oil deposits in these hills, community land control has protected them against exploitative extractionism. Community autonomy and control over land and traditional land management practices have effectively turned these areas into protected zones, despite the lack of official designation.

With a quarter of its ecosystems completely intact, the Eastern Himalaya is a landmark for conservation efforts globally. Around 60 per cent of the region is still under forest cover and within India, the Eastern Himalaya represents over three quarters of its intact forest cover.

WHY NOT HABITATS AND PEOPLE? GETTING TO THE RURAL FUTURES MODEL

As a result, conservationists across the Eastern Himalaya are changing the way they work to actively make communities part of conservation activities. KTK-Belt in eastern Nepal works with indigenous communities to preserve their knowledge and empower them as educators for conservation awareness. International initiatives such as UN-REDD and GEF-Satoyama are partnering with indigenous communities in Nagaland and Meghalaya to restore forests and protect biodiversity within their lands.

Livelihoods are swiftly becoming the key to turning communities into conservationists. Conservation NGO Aaranyak, for example, works with women-led SHGs in communities on the fringes of Manas National Park to build livelihoods through high value fruit products, fisheries and weaves as an alternate to exploiting ecosystems and wildlife in the park. The Mountain Futures programme in Yunnan functions similarly, using agroforestry and smart farming to ease agricultural burdens on fragile ecosystems.

Back in elephant country, our real breakthrough happened when we reframed the question: why not forests and people? Changing the question birthed Rural Futures: a vision for community livelihoods through habitat restoration. Through this, communities would have stronger incentives to protect and nurture new habitats. In time, planned agroforestry along the newly restored forest buffer zones would provide a sustainable stream of income for communities.

The key was not just incomes, but changing the way people saw the earning potential of forests by restoring symbiotic relationships between people and forests – from commodification through destruction to natural capital through regeneration. Early successes in Udalguri and Balipara Reserve Forest showed this didn’t just look good on paper; it worked. In less than three years, communities earned over INR 10.3 million while restoring over 450 hectares.

.jpg)

A Phayre’s leaf monkey, also known as Phayre’s langur, clings to his arboreal home in Tripura, Assam. Phayre’s langurs live in groups on trees on the fringes of Tripura’s tea estates; they rarely descend from the safety of the canopies, but lately are being forced to due to deforestation. Photo: Manish Gadia

THE CHALLENGES

The Eastern Himalaya is a challenging terrain and as temperatures warm rapidly in the mountains, the race to save its fragile ecosystems grows ever more desperate. Big dams for hydropower such as the Teesta-V in Sikkim and the ongoing Yarlung Tsangpo hydroelectric project threaten to dry up river systems across the region, resulting in devastating consequences. Mining and big infrastructure development projects like road-building permanently disrupt habitats and wildlife corridors. The timber trade remains a lucrative source of income, flourishing despite being highly restricted by government authorities.

While the scale of these challenges are daunting, requiring international and corporate cooperation for long-lasting change, there are smaller, everyday challenges in the field that can and must be met head on. Poaching, encroachment for agriculture, limited livelihood and employment opportunities – all three must be combatted together to put a stop to the localised causes of biodiversity loss.

There are challenges within conservation too, as we discovered in the Balipara Reserve Forest. Invisible gendered social norms in participatory dialogues prevent women from being decision-makers within conservation programmes. This invisible barrier also bars them from accessing benefits tied to conservation activities, while also burdening them with the bulk of labour. It took us multiple dialogues and negotiations, in Balipara, to bring men on board with paying women workers equally and having them participate as peers in the Joint Management Forest Committee.

Flowing through Sikkim, West Bengal and Bangladesh, the Teesta river supports abundant life in the forests and communities that abound it. The National Hydro Power Corporation’s (NHPC) plan to build around 28 dams (of which five have already been built) along the river threatens to destroy this rich biodiversity, destabilise the fragile geology of the region risking earthquakes and landslides, and drown the communities that reside near it. Photo: Samsul Huda Patgiri

THE FUTURE

It’s August 2019, the height of planting season in the Balipara Reserve Forest and rain is coming down in torrents as women from the Bodo, Garo and Nyishi communities involved with the project congregate in an empty school hall for a special workshop on what they see as the challenges for the future. Months of us working to get them equal pay and a voice on the JFMC have paid off and it’s not long before they’re telling us all about their hopes for the future.

We’ve come a long way since our early vision for Rural Futures. What began as a vision for livelihoods through habitat restoration has now morphed into something bigger: can restored habitats and natural capital revolutionise social service and assets provision? We think it can, with its under-accounted values plugging in the financial gap that forest fringe communities across the country face. As the women tell us about the need for education, for better healthcare and for greater community autonomy and political empowerment, we can only nod along in total agreement. As long as communities lack access to these universal basic assets and services there will always be a risk of them turning on habitats and ecosystems to find the cash to make ends meet.

Delivering universal basic assets through natural capital is a distant dream, and sustainable development and conservation have a huge gap to bridge before they meet in the middle to achieve an equitable and just transition to a Nature Needs Half future. Community-led conservation in the Eastern Himalaya still has a long way to go, even if the women of the Balipara Reserve Forest can now imagine a future full of possibilities: verdant hills, elephants passing peacefully through, autonomy and control over land and livelihoods that allow them to live interdependently with nature as they would like to.

Back at the workshop, the rain is easing off and everyone is restless to get outside and get planting. The women’s enthusiasm is infectious and for a moment anything seems possible: there are hundreds of thousands of saplings waiting to be planted – and a whole new future along with it.

COMMUNITY CONSERVED AREAS

Who: Indigenous communities across Nagaland, supported by GEF-Satoyama

Where: Nagaland, India

What they’re doing: Wildlife protection, biodiversity documentation, habitat preservation, regenerating and restoring forests, conservation of nesting sites, hunting bans, and managing areas for sustainable bioresource use.

The impact: 407 areas, over 245 sq. km. of Protected Areas, 1/3 of all villages in Nagaland involved in conservation, restoration of degraded ecosystems, increased natural regeneration within forests, people’s biodiversity registers documenting traditional ecological knowledge, and improved protection of biodiversity.

CONSERVATION & LIVELIHOODS

Who: Aaranyak

Where: Manas National Park, India

What they’re doing: Providing alternate, ecologically non-destructive livelihoods through agroforestry, weaving, and apiculture to communities on the park fringes.

The impact: 116 SHGs, bringing back traditional knowledge into livelihoods, minimised dependency on forest resources through poverty reduction and alternate livelihood streams

COMMUNITY CONSERVATION & AFFORESTATION

Who: 10 indigenous Khasi councils, UN-REDD

Where: Khasi Hills, Meghalaya, India

What they’re doing: Restoring degraded forests, protecting old-growth forests, forest Management, reducing dependency on fuel-wood through energy-efficient cooking stoves, improved livelihoods through carbon rights, and fi relining to protect forests.

The impact: 62 communities involved, over 27,000 hectares of forest land protected, expansion of habitat areas, improvements in wildlife connectivity, community-based species monitoring, conservation of cloud forest ecosystems and biodiversity, and reduced forest fires.

THE VERTICAL UNIVERSITY

Who: KTK-Belt

Where: East Nepal

What they’re doing: Documenting indigenous knowledge, empowering local farmers and communities to become conservation educators on species diversity and protection in east Nepal, protecting and restoring habitats and biodiversity from Koshi Tappu Wildlife Sanctuary to Kanchenjunga, livelihoods programmes for local farmers for wildlife friendly farming and ecotourism, habitat mapping and research.

The impact: 33 learning plots for place-based education in conservation led by indigenous communities, identifi cation of 660 plant species, and documentation of habitats and watersheds.

RURAL FUTURES

Who: The Balipara Foundation

Where: Assam, India

What they’re doing: Participatory habitat restoration as a source of livelihoods, documenting traditional knowledge, building alternate livelihoods through ecotourism, organic weaves and agroecology, and using natural capital to deliver access to universal basic assets and services.

The impact: 22 communities received INR 11.6 million in income through habitat restoration, 9,000+ people impacted, and 1,200 hectares of forest restored.

Ranjit Barthakur is the President and Founder of the Balipara Foundation, and one of the leading minds behind the proprietary concept, NaturenomicsTM. Saurav Malhotra oversees operations at the Balipara Foundation and is co-founder and designer of the Foundation’s proprietary action framework, Rural Futures. Joanna Dawson is involved in developing organisational strategy and thought leadership at the Balipara Foundation.

.jpg)