Expanding Tiger Conservation

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 40

No. 4,

April 2020

By Raghu Chundawat and Joanna Van Gruisen

We had crawled onto a small ledge overlooking one of the many sehas (gorges) that are a key feature of Panna. One of the collared tigresses had been located here and we suspected that she had given birth. We sat quietly in the shadows with the sun behind us, inconspicuous to the animals below even if they were to look up. We watched a langur hop along the ledge further away as a few Indian Vultures swooped by. And then, the moment we were waiting for. The tigress known to us as 120 for her radio frequency position, appeared at the top end of the gorge. She walked over the rocks below, looking magnificent in the glow of the morning sun, her coat lustrous against the black boulders. When she was almost in line with us, she veered right towards the opposite side and entered a small cave. The opening had an almost leafless creeper across one side of the entrance. Within a few moments, she had lain down inside and was looking in our direction. And suddenly a movement. We held our breath! So small, they were hardly bigger than her paw, first one and then a second, two cubs emerged to greet her, stumbling clumsily on their short legs. The mother gently licked and caressed them with her paw before lounging back to suckle them. They were hardly a week old. What a privilege!

The tigress 120 or Sayani as she was known in the BBC documentary Tigers of the Emerald Forest, was one of three sisters, daughters of Baavan, the ‘queen’ of Panna and the most successful female tigress of that time (1996-2005). She and her three daughters were all collared as part of Dr. Raghu Chundawat’s tiger ecology project initiated at the Wildlife Institute of India. But Sayani won our hearts more than all others. She had the gentlest nature and was the most comfortable around jeeps and elephants, which meant we shared more of her life than we did of the others. Where other tigers would seek a secluded shady spot, she would be found in the most open part of the grassland or forest. We knew her from when she was a cub, and watched her settle into her territory, adjacent to that of her mother’s, and raise her litters. It was therefore all the more heartbreaking when she came to an untimely end in a poacher’s snare while still in her prime at six or seven years. Those young cubs we had watched in the cave must have died too as they were still too small to be independent. Their father met his premature death not many months later.

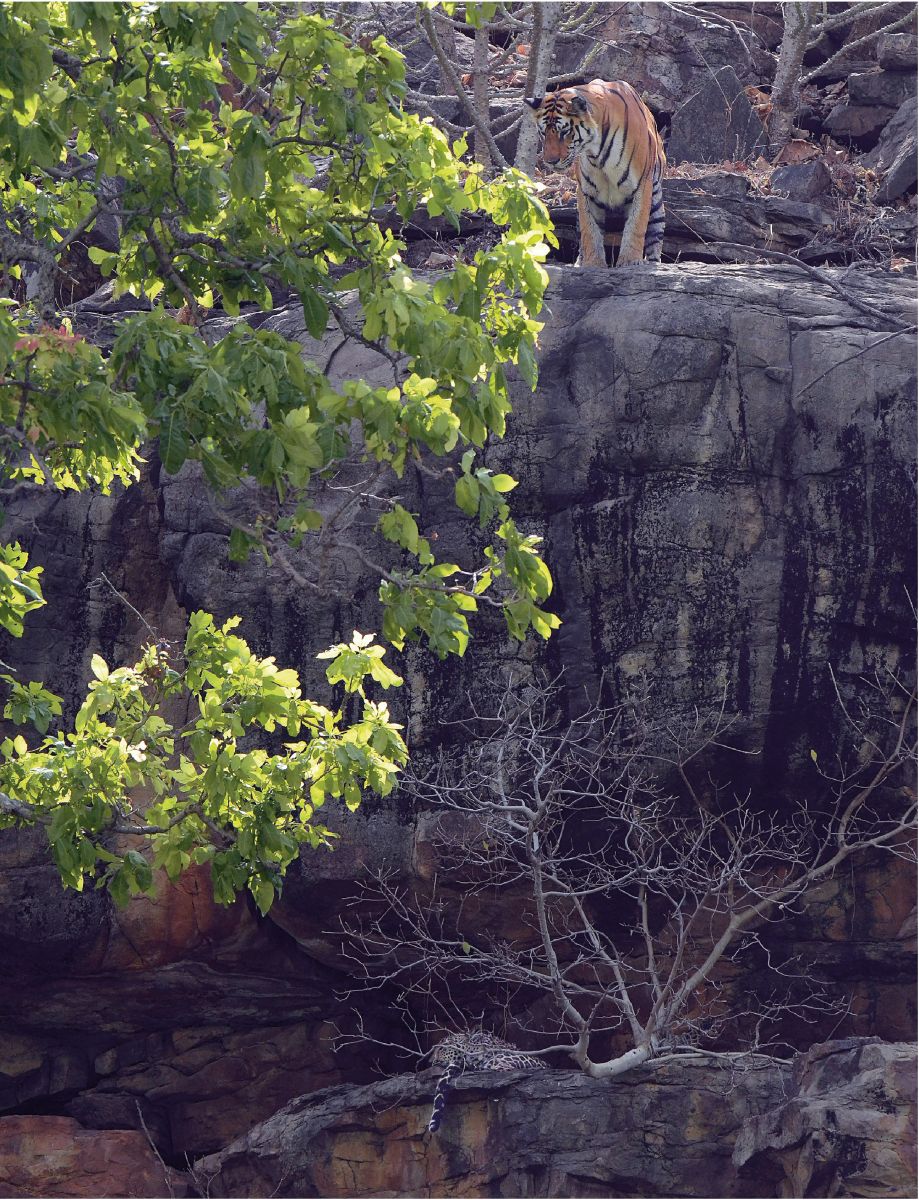

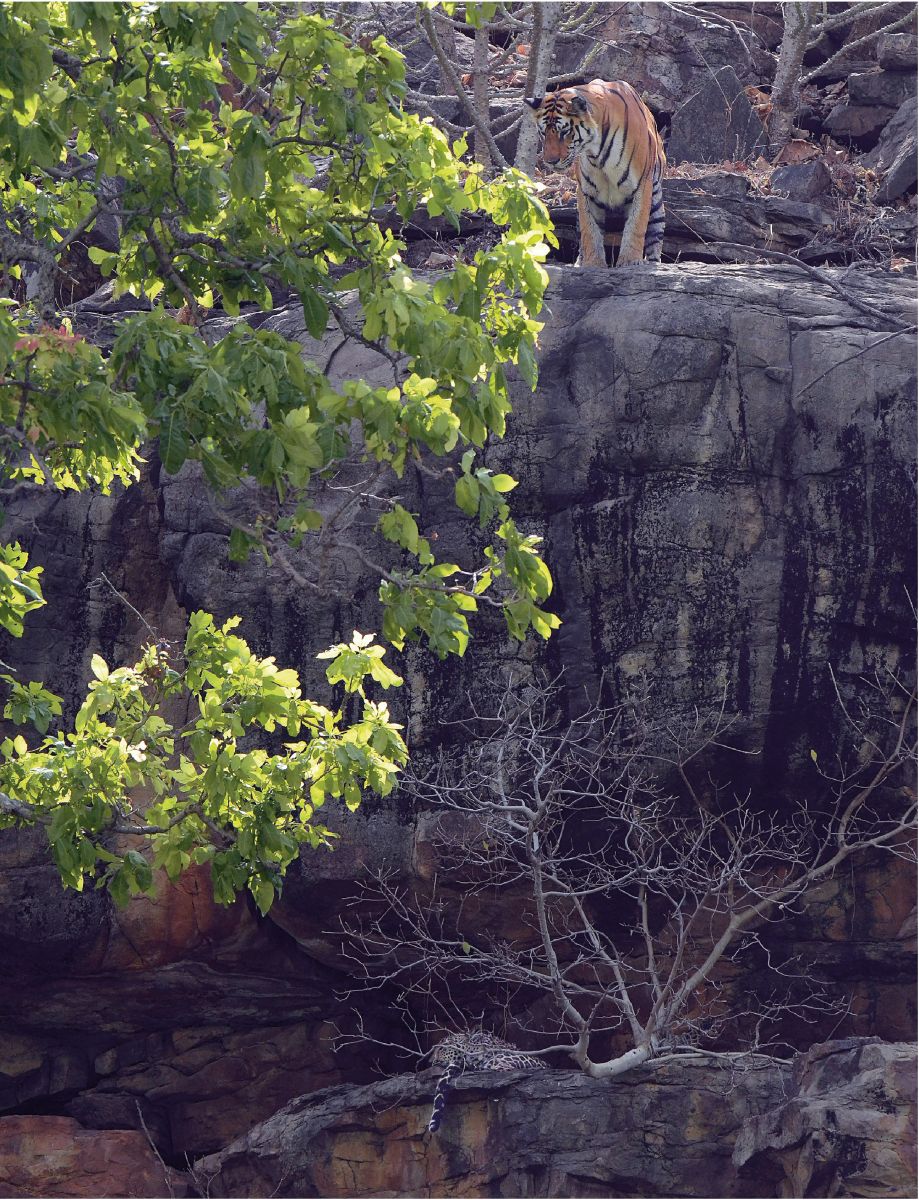

A tiger peers over the rocky cliffs of Panna at a leopard lounging in the shade. Though the successful reintroduction of tigers in the region is a laudable feat, it is premature to celebrate a countrywide population increase, considering the numbers are only a few hundred more than 50 years ago. Photo by: Devendra Gogate

An Increasing Tiger Population?

That was the sad state of Panna around a decade ago. Since then there has been a successful reintroduction programme there and tigers are flourishing again. However, has there been an India-wide increase? In 2006, India initiated a four-yearly nationwide camera-trap tiger census. Since the first announcement in 2008, the numbers have been rising and each rise is greeted with ever increasing fervour. In 2019, an estimate of 2,900 tigers was announced and a doubling of the tiger population was claimed.

The methodology used to arrive at these estimates has been critiqued by several experts on theoretical and other technical grounds. The adult tiger population may not have changed much but, by tweaking and adding a younger cub population to the total number (those above 12 months instead of those 18 months and older), a different perception was created; in earlier years, increased coverage area had helped them raise the estimate.

The celebrations around the announcement and increase in tiger numbers are of concern since they build an environment of conservation amnesia – a syndrome of shifting baselines. In people’s minds, the baseline has shifted from 2,500 tigers in the late sixties to 1,400 in 2008. The celebrations lead us to forget that in 1969, when India told the conservation community that only 2,500 tigers were left in India, this low number shocked the world. The situation was considered so drastic that India stopped all hunting and took extraordinary steps, launching Project Tiger to save the tiger. Fifty years later, with only a couple of hundred more tigers added to the original numbers, we celebrate the same number as a huge success. Those of us who review it with historical reference, cannot be as excited. Considering the political will, legislation support, funds, expertise and time that was made available for tiger conservation, 5,000 would be a more laudable figure.

Technological advancements such as camera trapping and geo-tagging have facilitated easier counting and tracking of tiger populations; this is vital as most of these populations are small and isolated and thereby more susceptible to the threat of local extinction. Photo by: Dnyanesh Rathod.

Is There Hope?

The most impressive achievement of tiger conservation in India – rarely lauded - has been its ability to hold on to the tiger’s geographical distribution. Not many conservation programmes around the world are able to achieve this. In India, in spite of a few hiccups, we still have tigers occupying all the habitats they were occupying at the beginning of Protect Tiger. It was indeed a long-term vision of the programme that distributed Project Tiger conservation areas or tiger reserves according to geographical importance. But many of the areas occupied by tigers today are small and isolated. When this is so, local extinction threats are operating simultaneously on each of them.

Unfortunately, we don’t see a road map or long-term vision in these four-yearly reports to address these issues. What otherwise is the purpose of these exercises? Many of the areas occupied by tigers are small and isolated – how can we connect the populations and make them viable? How are we going to protect our non-Protected Area (PA) tiger populations and habitats – outside the designated tiger reserves – and expand the range?

The eulogising of new numbers creates a somewhat complacent perception and some tiger “experts” are even taking advantage of the celebratory atmosphere to plant stories in the media that India does not have enough space for more tigers. This perception exists because some cannot see the possibility of conservation beyond the Protected Area boundaries. But if we approach the issue with a different perspective, where the tiger adds value to the forest, then there are plenty of places still available. We believe that not only do tigers need forests, but the forests also need the tiger.

The most impressive achievement of tiger conservation in India – rarely lauded - has been its ability to hold on to the tiger’s geographical distribution. Not many conservation programmes around the world are able to achieve this.

Reconsider the Conservation Model

The current conservation approach in India is entirely dependent on one model: this is an exclusive conservation model based on a PA approach. Within the PAs, all threats are removed. This approach has played a very significant and successful role in the wildlife and biodiversity conservation of India. However, the problem with this model is that its conservation reach is limited and with a growing population, in numbers and aspirations, expansion for the PA system is finite.

According to the 2014 National Tiger Conservation Authority tiger report, Madhya Pradesh has 89,000 sq. km. of tiger habitat. Tiger presence was recorded from 15,000 sq. km. of this and approximately 8,000 sq. km. is protected. The rest of the 7,000 sq. km. tiger occupied area is beyond the reach of the present conservation model. If we include buffer zones (5,000 sq. km.) as part of the conservation area, then hardly any tiger population survives beyond the PA boundaries. This shows how detrimental it is to entirely depend on only one conservation model. It is also why some conservationists who only believe in this exclusive conservation model, cannot see beyond it and believe that there is no space left for tigers in India.

In the non-protected habitat, the tiger, or indeed any wildlife, can only survive with the goodwill of the people who live in these areas. The exclusive conservation approach that India has adopted leaves communities to participate on a voluntary basis: the only reasons given to them are the ethical and moral ones. But why would they want wildlife in their neighbourhood when they already struggle to survive and these are but additional threats to their livelihood? Our surveys have revealed that communities are not against having wildlife in neighbouring forests per se, but, understandably, they do not want any additional threat that makes achieving a livelihood more difficult.

The local economy of villages in these habitats is dependent mainly on agriculture, labour, livestock and forest produce. In the past few decades, due to climate change and other factors, the health of this economy has deteriorated and is fast becoming unsustainable. Thus, a harmony that existed for centuries is breaking, and the demands on the forests and wildlife are increasing, bringing damage in their wake. In this struggling economic environment, conservation messaging can have little impact if it is left for people to participate on a voluntary basis.

There is an urgent need to extend tiger conservation beyond the boundaries of Protected Areas, mapped at the beginning of Project Tiger. Protecting tiger corridors to enable dispersal and interbreeding for a viable gene pool diversity is vital to the survival of tigers in India. Photo by: R. P. Omre.

If we want to maintain the forests and encourage conservation in these areas, we need to look to the financial security of the communities; help is required to bring change in these remote areas, to build new economies that are contemporary but still conservation and nature-friendly and even capable of reversing ecological degradation. Only by focussing on improving their livelihoods can we expect

people to participate in conservation. Conservation measures must bring welfare and direct benefits to them.

Unfortunately, these populations are not only poorly educated but also have limited skills to deal with an increasingly urbanised world. The dilemma therefore is how they can be assured of jobs and livelihoods. How can we ensure that local communities living next to our PAs become the primary beneficiaries of the conservation initiatives? Is it possible to create conservation-based economies?

Around the world, tourism is used effectively as a conservation tool. Scotland’s nature tourism attracts around 1.8 million international visitors a year. We calculated that Madhya Pradesh – nearly four times the size of Scotland and with many charismatic species like tigers and leopards – receives less than 10,000 wildlife tourists from overseas annually. Scotland generates over £1 billion (roughly INR 9,500 crores) from their visitors. Clearly M.P. – and the rest of India – is missing a golden opportunity!

Rethink Wildlife Tourism

One of the problems is that wildlife Tourism in India is run no differently from tourism in Agra or Khajuraho. The model is not designed, promoted or encouraged as a conservation tool. We expect conservation value from it but we have left it to grow with market forces. It has developed without clear conservation goals and without appropriate guidance and direction, so now many conservationists even include tourism as one of the serious threats to wildlife. From a potentially major support, it has slid to being regarded as a menace.

This is more than unfortunate when it has the potential to be an important conservation partner. We believe that it has great potential if we can spread nature/wildlife tourism widely across non protected habitats. Even now, our research in M.P. shows that tourism brings major financial benefit to local communities and plays a major part in generating goodwill towards wildlife in the areas where it operates. Almost 45 per cent of the revenue generated goes into the local economy and another 10 per cent goes directly to conservation through fees. It also provides substantial employment opportunities for local communities. Handled sensitively, the tourism industry can play a significant role both in expanding wildlife habitats and in bringing improved livelihoods and development to remote communities in the villages of India. The tiger can be a major catalyst in this – to be a forest and livelihood saviour. In India, almost all wild habitats are controlled by one government agency, the Forest Department. It has followed and continues to follow, only one – exclusive – model of conservation. We believe that now we need to look beyond this. Parallel inclusive conservation models are needed to run simultaneous to the existing one; models that will strengthen the protected area approach.

Through public-private partnerships or community private endeavours, it is possible to extend a conservation model beyond PAs and thereby protect both biodiversity and the livelihoods of communities. Photo by: R. P. Omre.

With little scope to enlarge the PA network, if allowed, public-private partnerships (PPPs) or community private endeavours could fill the gap and this could also enhance the conservation orts of the Forest Department of all Indian States. But the government must open its arms – not keep everyone at arm’s length. It needs to recognise its friends and join hands with them. There are many square kilometres of wildlife habitat outside the PA system where such partnerships could be developed, allowing biodiversity conservation to be extended.

The tiger need not be the only catalyst or beneficiary: we can have such PPP models for wetlands, breeding programmes and simply to preserve areas with natural beauty. We look forward to conservation-based development alternatives, where tiger presence will add enough value to the forest and sufficient livelihood to the community to justify and arrest exploitative developments such as dams, mining and urbanisation.

Originally from the U.K., Joanna Van Gruisen has lived in the Indian subcontinent for over three decades. She is a writer, photographer and conservationist. Raghu Chundawat is a noted tiger biologist and author of The Rise and Fall of the Emerald Tigers. The duo run an ecotourism venture near Khajuraho and the Panna Tiger Reserve.