Expedition Angria Bank

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 40

No. 12,

December 2020

By Vardhan Patankar

When you think of coral reefs in India – Andamans, Lakshadweep, Gulf of Mannar and Gulf of Kutchh come to mind… not Angria Bank, located approximately 65 nautical miles (or about 120 km.) offshore from Vijaydurg, Maharashtra.

The Angria Bank is a submerged plateau, a shallow region formed during the Holocene sea-level rise thousands of years ago. Historical records indicate the area was a stronghold of Kanhoji Angre, one of Maratha Emperor Chhatrapati Shivaji’s first Admirals. Angre used the submerged bank as a battleground where he fought against enemy ships and protected the Maratha empire from foreign invasions.

Even though visiting Angria Bank has always been on the radar of WCS’s Marine Programme, the real impetus came in July 2019, when the former Additional Chief Conservator of Forests, N. Vasudevan convinced us to explore the area. It appeared to be a far-fetched goal, but Prakriti Srivastava, Country Director, WCS-India, encouraged us to launch an expedition to Angria.

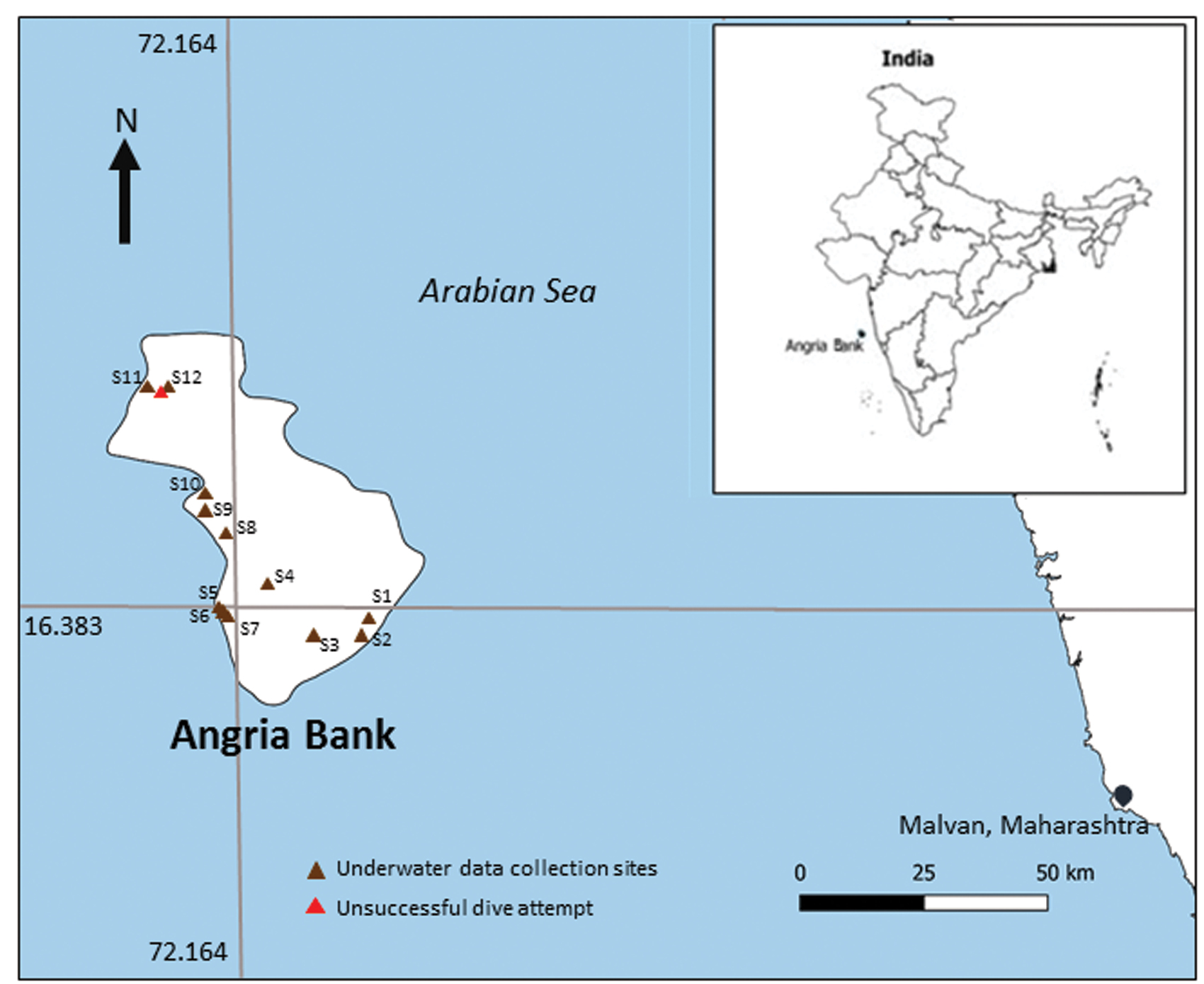

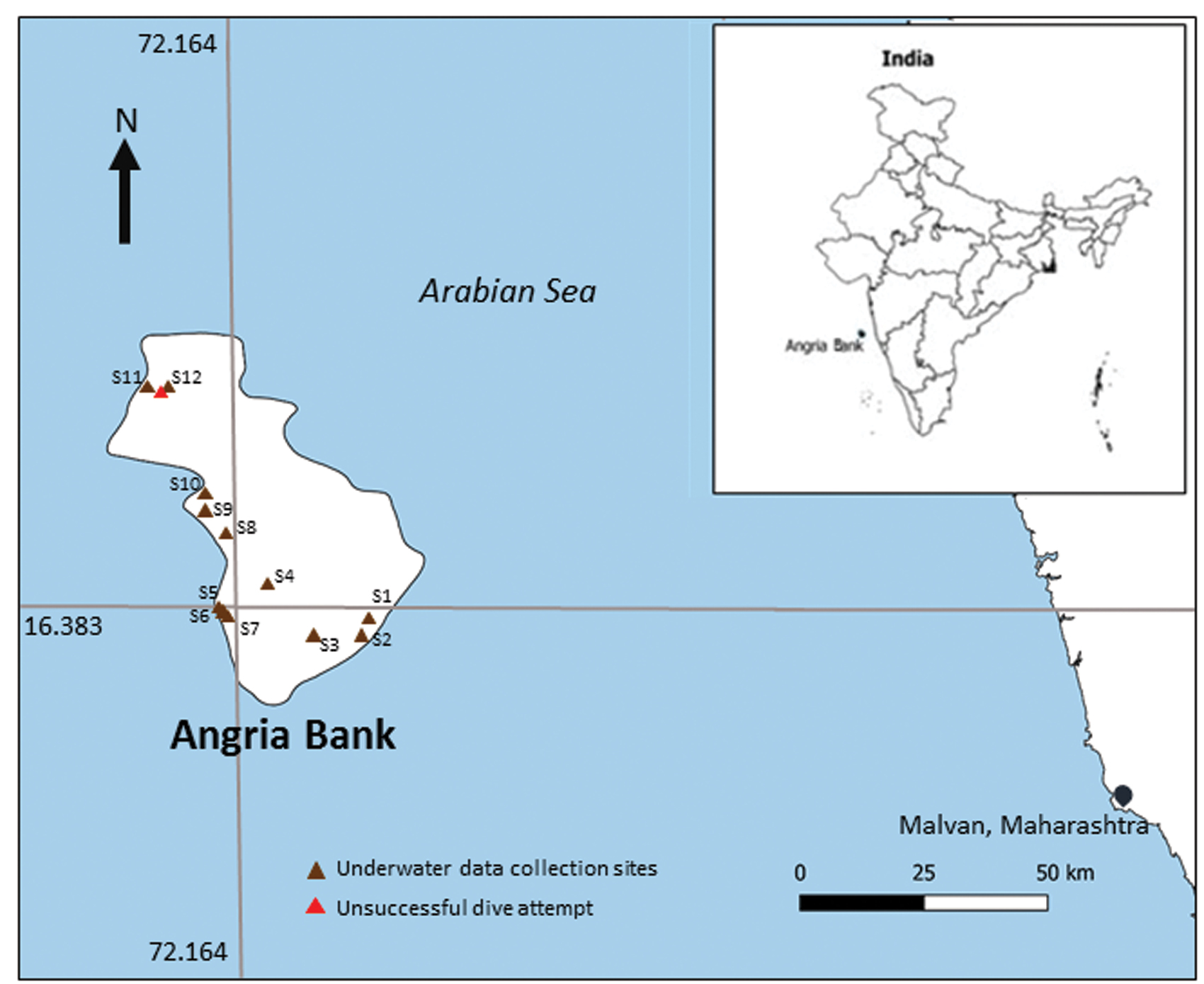

The author led the team that conducted a marine survey of the Angria Bank. In the course of several dives, they spotted bottlenose dolphins, barracudas, silver-fin jacks, groupers, snappers and thousands of reef fish that displayed a stunning array of hues. Map Courtesy: WCS-India.

Journey into the Sea

On December 19, 2019, we were up before dawn. A beautiful morning sun sparkled gold across a gentle sea. Within 15 minutes of leaving the Kochi port, we sighted a pod of Indo-Pacific humpback dolphins Sousa chinensis, cavorting, idling and feeding. The journey to the Angria Bank took 52 hours, time enough to plan and prepare. Exactly six hours and 30 nautical miles off shore, the cell phone range vanished, as did any sight of land. All round Sagar Sampada, our home for the next few days, were relatively smooth seas, a gentle breeze and the throb of the engine that drove us along at a steady speed of seven or eight nautical miles per hour.

We chose to use the double-observer survey method for our marine mammal survey. Two primary observers (facing port and starboard respectively) used the Big Eye binoculars mounted on the vessel bridge to observe, identify and count birds and marine mammals. Others used handheld binoculars, mainly to spot dolphins. We took turns to do shifts until dusk… without luck. Night came early and soon we were sailing under a canopy of a million stars. We gazed at cirrus clouds, constellations of stars and long strides of flying fish, as our ship swayed gently through dark blue waters. By the second day, when we crossed the continental shelf the water looked much darker. The occasional tern soared overhead. We did spot a few ships in the distance, but for the most part, it was just us and the seemingly endless sea. We continued our lookout for dolphins and other mammals. The wind was against us; we were still several hours from reaching Angria Bank and saw more flying fish gliding long distances, touching the surface of the water intermittently. We also spotted gulls, petrels and skuas. Finally, before evening turned to night, we sighted a pair of pantropical spotted dolphins Stenella attenuata and an Indian ocean bottlenose dolphin Tursiops aduncus that rode our bow for a full 10 minutes.

On our third day, the sea felt exceptionally calm. The texture and colour of the water was a clear, wonderful blue. At 10 a.m., to our delight the captain announced that Angria Bank was just 30 minutes away.

Named after their spheroid, grooved appearance, brain corals are a type of stony, hard coral common in shallow warm-water reefs across the world’s oceans. Photo:Vardhan Patankar.

Diving at Angria Bank

As the popular saying goes – in military operations, nothing goes according to plan. Perhaps that is apt for field biology as well. In the 34 years that the research vessel FORV Sagar Sampada has been operational, no work has been carried out that involved scuba diving. None of us had ever dived off a large ship before and trial and error was therefore the order of the day. As the first group of divers readied for an exploratory dive, one diver excitedly jumped off early and the others soon followed suit. But our outboard engine refused to start! And by the time it did, the five divers had drifted apart, pulled along by strong surface currents. There was overall panic among the divers and those onboard. Mercifully, all the divers soon clambered into the inflatable. But one of us got stung by a jellyfish and the dive had to be aborted. After administering first aid treatment, we changed our dive plan. We next chose to climb down the pilot ladder into a smaller inflatable, into which we lowered our SCUBA gear and found our respective dive sites using handheld GPSes and depth finders.

On our first exploratory dive, it took us nearly 30 minutes to find a site where the depth was less than 28 m. As we plunged into the crystal-clear water, we heard nothing but our own breathing. Once we hit the top of the plateau, we saw a school of giant silver-fin jacks and barracudas in the dappled sunlight. Curious groupers glided past and on the sea floor, we watched a veritable symphony of multicoloured reef fish with wonder. We swam awhile in the dense ‘thicket’ growing along the reef edge amidst a profusion of vermilion red, canary yellow, citron orange, royal purple, all against the backdrop of an electric blue sea. In a wonderland that few had ever seen before, we watched groupers and snappers jostle for space in coral crevices, looking for all practical purposes as if engaged in a game of musical chairs. In eighteen minutes, we ascended slowly, with two safety stops, to prevent decompression sickness, caused when the nitrogen in human bodies expands too quickly.

Our first dive was beyond delightful.

Expedition divers were astonished at the fecundity of fish populations in the Angria reefs where they saw impressive species such as this honeycomb moray eel Gymnothorax favagineus. Photo:Vardhan Patankar.

Expedition divers were astonished at the fecundity of fish populations in the Angria reefs where they saw impressive species such as this honeycomb moray eel Gymnothorax favagineus. Photo:Vardhan Patankar.

Execution of Surveys

As we were diving in unmapped habitats, we had no way of predicting what we might encounter underwater. The average depth of the Angria Bank was over 25 m. in most places and that limited the time we could spend underwater. We planned it such that five of us would do the data collection, with one person in the inflatable rib to maintain contact between the dive team and our ‘mother ship’ Sagar Sampada. Apart from filming and photography of marine biodiversity, we laid transect tapes to collect data on reef fish, invertebrates, corals and algae.

A close up of brain coral reveals the intricate patterns of its polyps. A diversity of corals was recorded, interspersed with dense microalgae across the bank. Photo:Vardhan Patankar.

A close up of brain coral reveals the intricate patterns of its polyps. A diversity of corals was recorded, interspersed with dense microalgae across the bank. Photo:Vardhan Patankar.

The reef here was different to those where we usually dived. Some sites were studded with corals and marine life, others clothed by dense macroalgae interspersed with sand. Occasionally, we were hit by cold currents and intense swells that were difficult to deal with. After every dive, we took a good one-hour safety stop, strictly following our dive-computer safety algorithms. Each day, we witnessed something new and unusual and the visibility stayed great and unchanged. At many sites, red whip corals rose like lilies from beneath the fans, with a host of small fish going about their business in between. There were thousands of fish and invertebrates of different shapes and sizes and colours, all busy doing what marine creatures do. Groupers were abundant at most sites. Eagle rays swooped in, moving like birds of the sea. Large tuna and sharks cut the water above us as we crawled through underwater rocks to avoid being swept away by strong currents. We were aliens in the land of moray eels, scorpionfish, wrasses, and literally thousands of fish.

Refilling scuba tanks, washing cameras and dive gear, data entry, followed by intense discussions to plan more efficient dives took over most of the evenings. Oranges, dry fruits and farsaan (crunchy Indian snacks) kept us going between dives. Post-dinner, the ship was manoeuvred across predetermined lengths and breadths, following structured transects. We used the onboard Electronic Depth Profiler (EDP) to map the Angria Bank floor that ranged between 16 m. to 32 m., and revealed an undulating bed, whose average depth was 24 m. The verge of the bank plunged from between 28 m. to roughly 70 to 300 m. in places.

The daisy-like polyps of the flowerpot coral of the genus Goniopora extend from their base, each tipped with 24 stinging tentacles to overcome prey.Photo: Vardhan Patankar.

The daisy-like polyps of the flowerpot coral of the genus Goniopora extend from their base, each tipped with 24 stinging tentacles to overcome prey.Photo: Vardhan Patankar.

A Sea of Change

After a few days, the wind picked up and the waves began hitting the ship from starboard. We stayed strong and undeterred, and regrouped with a new dive plan. We had to be sharp in terms of our reflexes, especially while lowering the inflatable boat and then descending into the water with our dive gear on. The most experienced amongst us dived, while others helped plan the dives. The surface currents were strong, but below, at the Angria Bank, the sea was largely calm. We continued our surveys, exploring new sites. Our days began with the sun’s first rays and ended with the last. We managed to complete surveying and exploring three or four sites each day. Some days it felt like we were in the middle of an action-packed James Bond movie: big fish chasing small fish, sharks cruising in search of prey and fish moving in and out of coral crevices like rush hour commuters in a subway. On other days all we saw was sand and vast stretches of macro algae… but even the gentle swaying of algae was hypnotic. On one occasion, a strong bottom current swept us along and we drifted so far that when we surfaced, neither our inflatable nor the mother ship was in sight! We held onto each other’s hands and legs to ensure that none of us were separated. Luckily, eagle eyes on the boat spotted us through binoculars and much to our relief arrived to rescue us from our not-very-welcome adventure. Another time, we surfaced so close to the ship that we had to scramble to get out of its way.

During the expedition, the divers spotted sea stars of the genus Protoreaster, which are often victims of the illegal, wildlife pet trade. Photo: Vardhan Patankar.

During the expedition, the divers spotted sea stars of the genus Protoreaster, which are often victims of the illegal, wildlife pet trade. Photo: Vardhan Patankar.

There was never a dull moment, but as the days went by, the sea became our new normal, with land just a faraway mark on our map. Ultimately, our expedition had to be cut short because the propeller of the inflatable went bust, but what a fantastic adventure it was and what a successful survey.

The return journey comprised discussions on time spent at sea, watching the sun rise and set, listening to the waves and marvelling at the grace of marine life. The expedition had opened a unique window to virtually unexplored reefs and its thriving marine life. In all we completed 66 dives and observed uncounted corals, reef fish, invertebrates, plus dolphins, sharks, sting and eagle rays. We were able to collect several new records of biodiversity. Our 14-strong expedition team with 16 SCUBA cylinders, six underwater cameras, 39 crew members, the 72.5 m. long FORV Sagar Sampada, and tons of adrenaline coursing through our veins, we returned to the Kochi harbour after spending 10 days at sea.

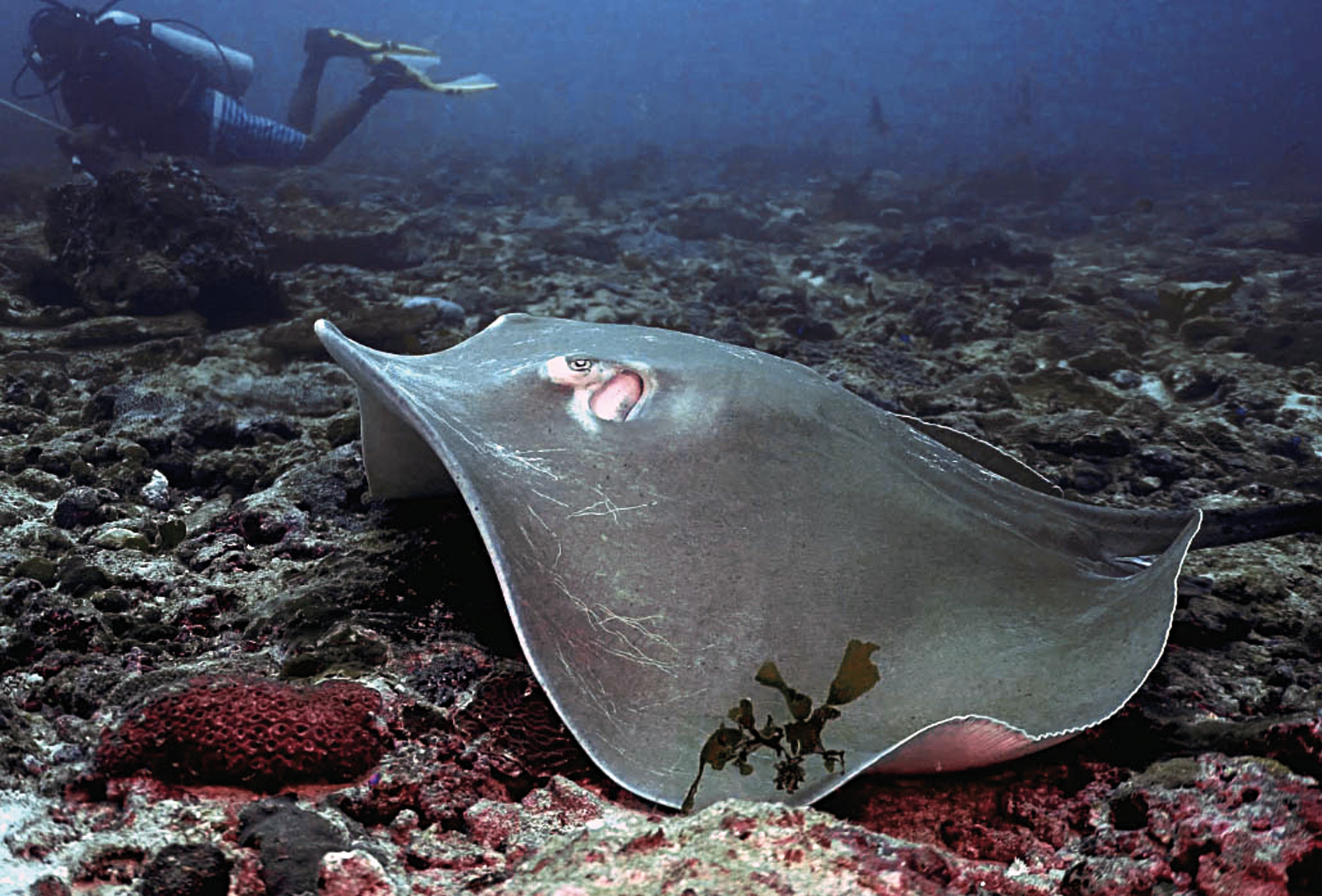

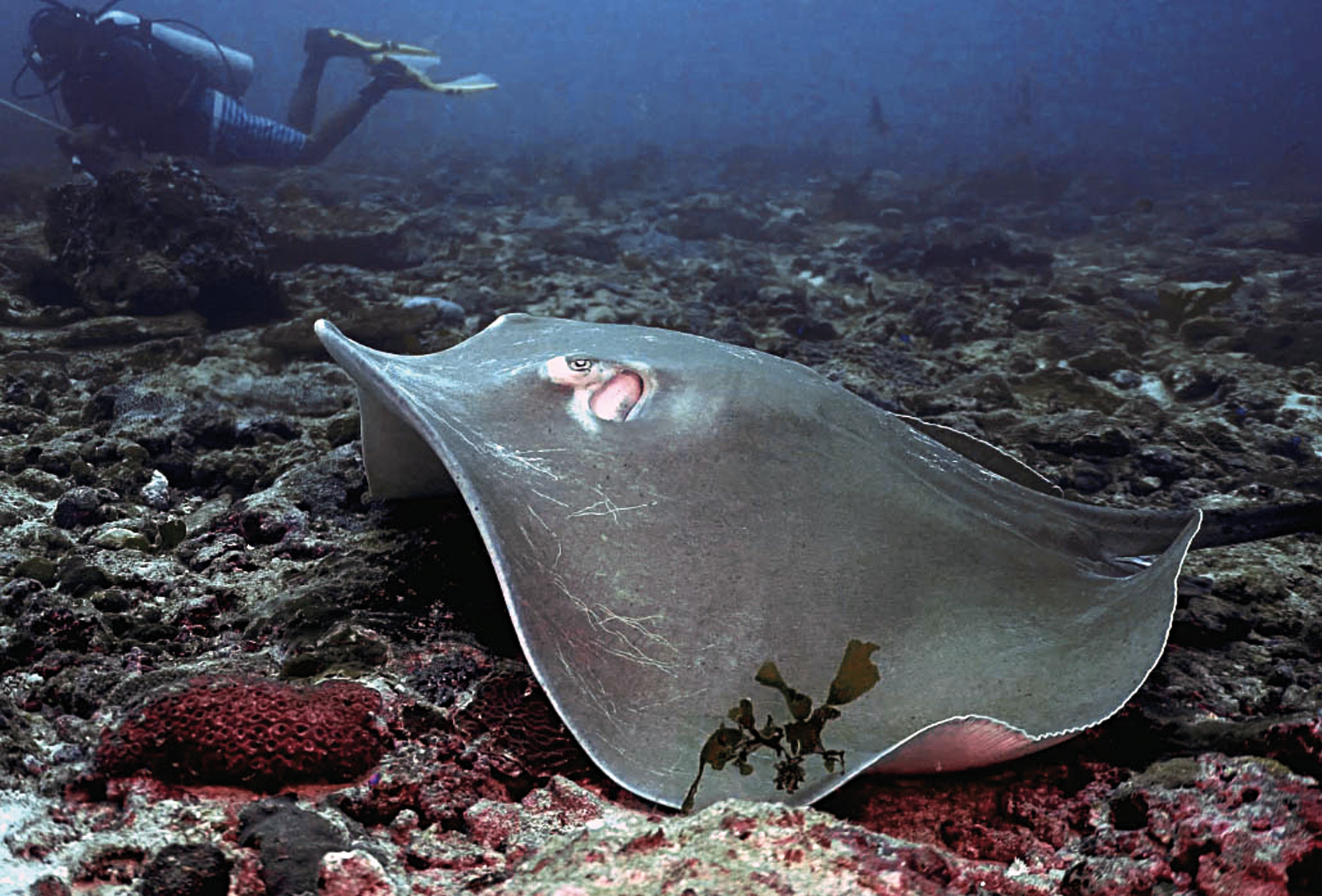

The Angria plateau was submerged on account of rising seas during the Holocene. Reefs soon took over the waterscape, offering sustenance to large marine creatures including sting rays. Photo: Jolchhobi films.

The Angria plateau was submerged on account of rising seas during the Holocene. Reefs soon took over the waterscape, offering sustenance to large marine creatures including sting rays. Photo: Jolchhobi films.

While reefs around the world are grappling with coral mortality at the hands of climate change, storms, cyclones and bleaching events, we wondered how and why the reefs and marine life at Angria Bank managed to thrive. What we do know is that the mysterious Angria Bank is a wonderland that represents the true wealth of India and the planet. We hope our findings will help conserve this unique ecosystem and create a roadmap for marine conservation.

Postscript: Having released our report on Angria, and as we write this piece for Sanctuary Asia, the Maharashtra Government has agreed to declare 2,011 sq. km. of Angria Bank as a Protected Area.

Preparing for the Expedition

Photo: Jolchhobi films

Photo: Jolchhobi films

To begin the process, we approached all seaworthy boats along the coast of Maharashtra. A few expressed support, but we did not receive a definitive answer. We reached out to several research institutions and pitched the idea of a joint expedition. M. Sudhakar, the former Director of the Centre for Marine Living Resources and Ecology (CMLRE) had the immense foresight to understand the significance of the expedition. He agreed to partner with us by providing the support of their research vessel FORV

Sagar Sampada, a 72.5 m long ship built in 1984 and equipped to carry out multidisciplinary research expeditions from oceanography and marine biology to fishery science. We then approached partner organisations and individuals who would contribute to the success of the expedition. Our team organised a tentative itinerary, survey plan, expedition team and necessary SCUBA and research equipment on a one-week notice. On December 16, 2019, we assembled at the Kochi port and spent two days planning the finer details of the expedition. We received clearance from the port authority and boarded the FORV

Sagar Sampada on December 18. The Captain of the vessel, Pradeep Chanan, and the Chief Scientist of the expedition, Dr. Hashim Manjebrayakath, who works with CMLRE along with 29 ship crew members welcomed us onboard.

The ship was fully equipped with spacious cabins, a helicopter pad for emergency evacuation and all means of recreational facility – from table tennis to a TV room. The kitchen was stocked with fresh supplies of vegetables, meat, fruits and beverages. As the ship is operated by the Shipping Corporation of India, under the Government of India, we had to follow fixed timings for meals. After a brief introductory session, a run-through of the dos-and-don’ts and a tour of the ship, the Captain announced that we would leave the Kochi port on December 19, 2019 with the first ray of light.

Marine Program Head of WCS-India, Vardhan Patankar pursues reef-related research with a critical eye and a fine-tuned appreciation for weirdness. He observes marine life within and outside coral reefs with wonder and amazement.