In Search Of The Elusive Finn's Weaver

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 39

No. 2,

February 2019

By Rajat Bhargava, Ph.D.

An ornithologist’s account of a bird that few people have even heard about, leave alone seen in India. The presence and absence of species is a key indicator of the ecological status of the Indian subcontinent, which is why the invaluable collections so carefully protected by the Bombay Natural History Society must be recognised as national treasures.

Few people have heard of the Finn’s Weaver. Fewer still have seen one. In fact, no one in Udham Singh Nagar – where most Finn’s Weavers cling on for survival – has actually set eyes on one. I should know! For the last two decades, I have been visiting the heartland of this district in Uttarakhand in pursuit of this rare bird. Of the four species of weaver birds found in our country, the Finn’s Weaver Ploceus megarhynchus is the least known.

In June 2016, a field visit to Assam and Arunachal Pradesh with the Director of the Bombay Natural History Society (BNHS) Dr. Deepak Apte and fellow ornithologist Dr. Girish Jathar paved the way for a new project. Dr. Apte was surprised when I explained that of the 188 threatened species (from the over 1,250 species found in India), it was vital to study endemics with a significant population in India. One such endemic, the Finn’s Weaver, despite being included in the IUCN Red List since 1988, had garnered little attention. Dr. Apte agreed to commission a study under the Sálim Ali Conservation Fund to assess the species’ population and conservation status.

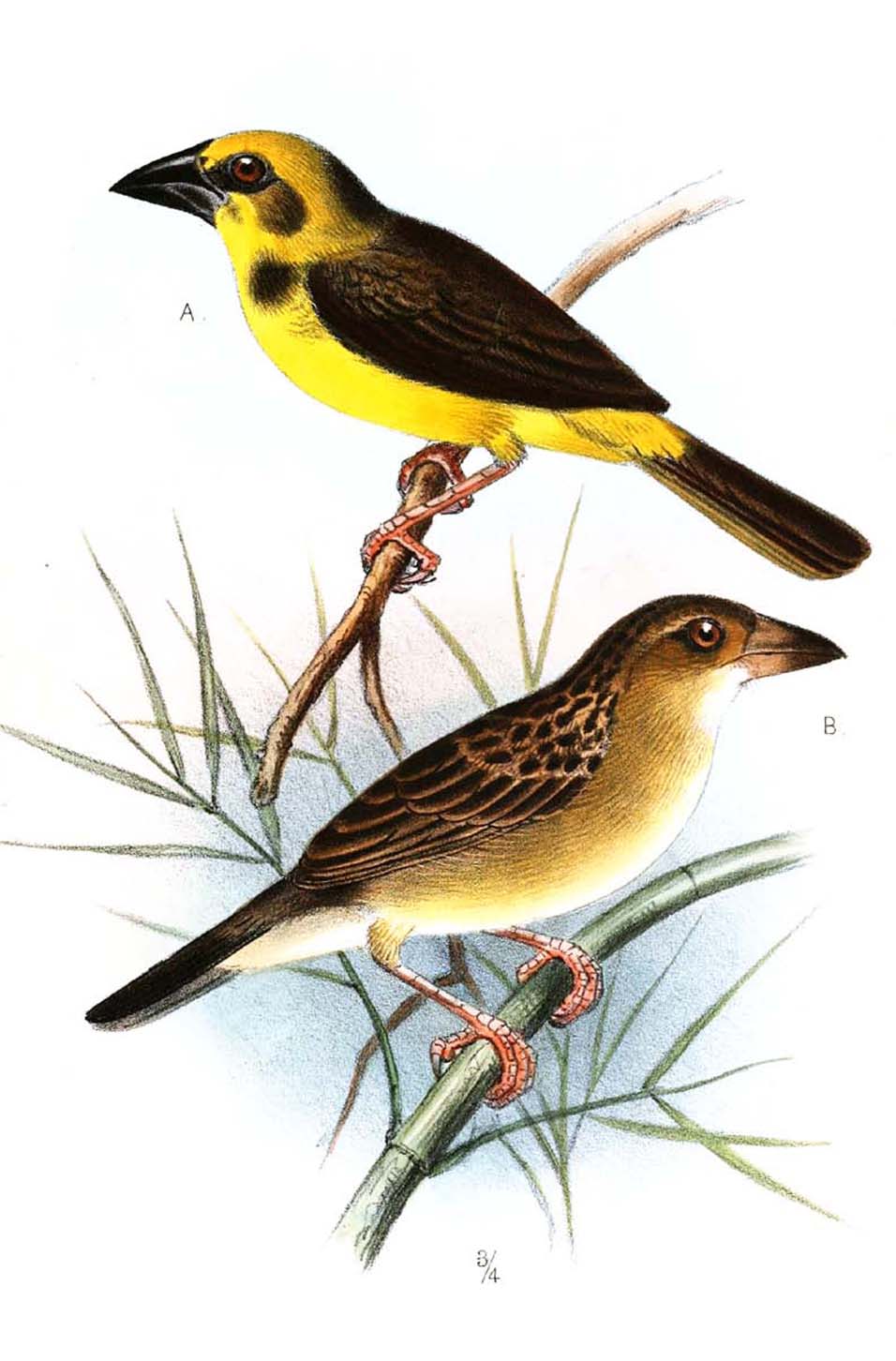

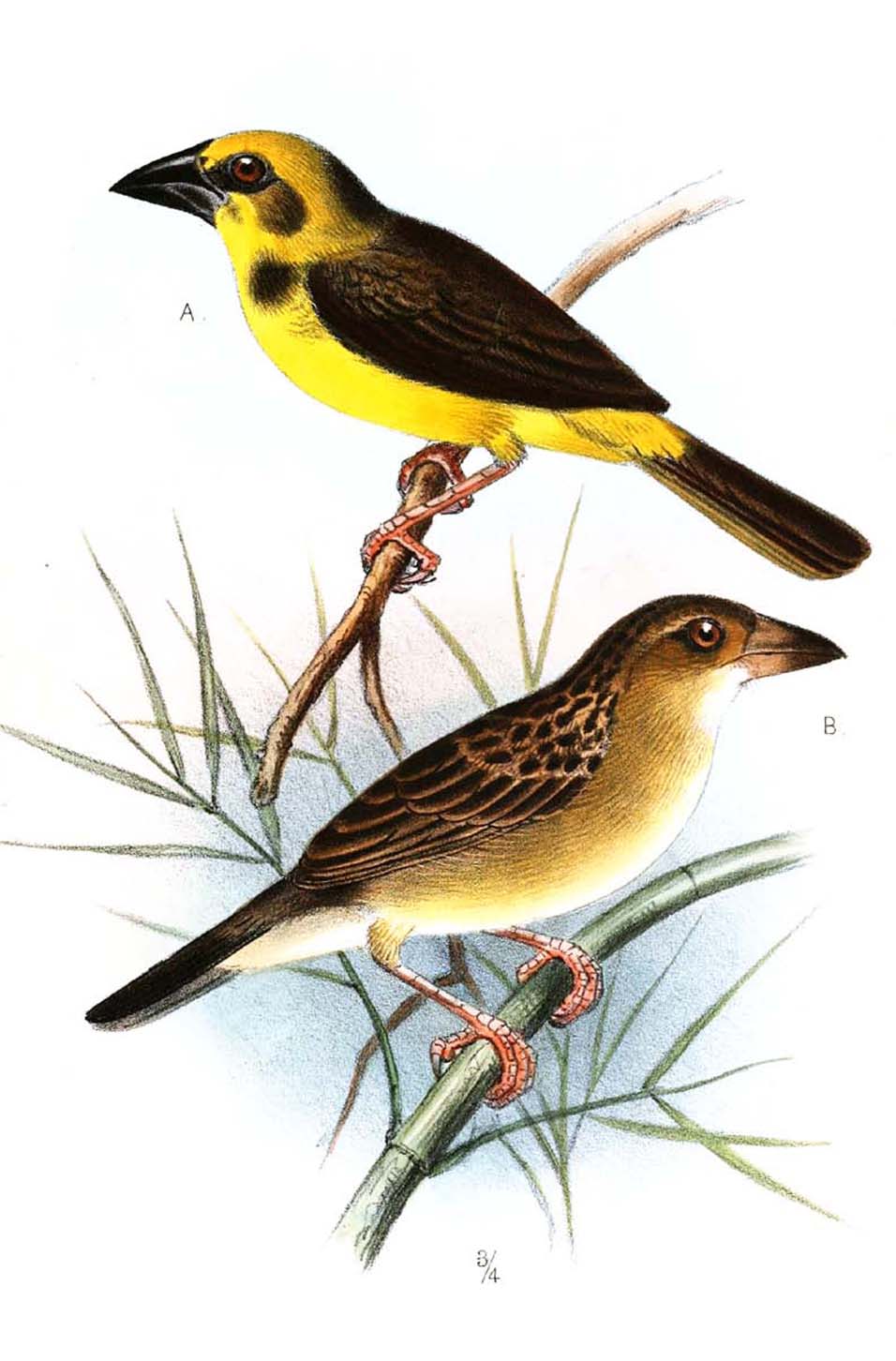

The Finn’s Weaver

Finn's Weaver male in breeding season. Photo: Rajat Bhargava.

Finn's Weaver male in breeding season. Photo: Rajat Bhargava.

Distributed locally in the lower

Terai from the plains to 1,300 m, the Finn’s Weaver is endemic to India and Nepal with two recognised subspecies –

Ploceus m. megarhynchus found in Uttar Pradesh, Uttarakhand and western Nepal, and

Ploceus m. salimalii, distributed in West Bengal and Assam. At 17 cm., it is larger than the other three Indian weavers. It is large-billed, heavy-legged and long-tailed and differs from other native weavers in that the female acquires a distinct yellow breeding nuptial plumage, but is less bright than the male. Unlike the three Indian weaver species that have suspended nests hanging from branches or fine twigs, Finn’s Weaver nests are large, globular structures, untidily but firmly woven with the entrance on one side near the top. At the onset of the breeding season, a flock of males will first select a tree, then strip leaves off twigs near their nests, denuding the upper canopies. This makes the nest-building activity easily visible. Just before the breeding season, all-female flocks can be observed. The Finn’s Weaver inhabits pure

Terai country with marshes and tall wet grasses sparsely dotted with isolated trees, especially silk cotton (

semal)

Bombax ceiba and shisham

Dalbergia sissoo. These are used for nesting and within areas interspersed with patches of rice and sugarcane cultivation.

The species is gregarious while moving in flocks and they feed together, primarily on rice grain, small seeds and insects. The birds are often seen foraging in ploughed fields or semi-ripe paddy and are particularly fond of hemp Cannabis sativa seeds. They also feed on invertebrates. Their calls are louder, harsher, and more ‘nutty’ than that of the Baya Weaver. The male song often chorused, may be rendered as

twit-twit-tit-t-t-t-t-t-trrrrr wheeze whee wee we, sometimes followed by a high

seep, seep. Calls that include a

skeer, skeer, skeer or tseer, tseer, indicate aggression.

Two distinct breeding periods are known; from May to the middle of July, and in August and September. In the first period, the birds build their nest in tree-tops prior to the monsoon, and in the second, low down in the Typha reed beds standing in water, after the rains have set in. An interesting feature is that a single male may make several composite nest units linked together with connecting walls appearing as partial fusion of each individual unit with the other. The nest units are not interconnected, each one being quite independent. The entire inside of the nest is lined, unlike other weavers, which line only the floor. The male exhibits sequential polygamy mating with two to four females one by one. Once a female has selected a nest and begun laying eggs, he goes to another female. Clutch size generally varies from two to four white eggs. Incubation is done by the female. It usually begins with the first egg and typically lasts 14 to 15 days. The young remain in the nest for 12 to 17 days. The Finn’s Weaver shows a preference to build its nest colonies on trees occupied by breeding pairs of the Black Drongo

Dicrurus macrocercus. The drongos are extremely aware of any potential predators such as raptors and crows, which they aggressively drive away.

Back to the Future

In December 1866, the Finn’s Weaver was discovered in India by Allan Octavian Hume based on two specimens of a previously-undescribed weaver bird in winter plumage, obtained from birds in trade. Hume, referred to by Dr. Sálim Ali as the ‘Father of Indian Ornithology’, was a Scottish civil servant and founder of the Indian National Congress. In his original description in 1869, Hume wrote:

“Also a new Ploceus, which I got in the Terai, much larger than any of our Indian species; and though closely resembling P. baya, it is nearly double the weight of that bird, with a bill fully half as large again. Dr. Jerdon agrees with me that this is a new species, at any rate to our Indian avifauna; and I name it provisionally Ploceus megarhynchus.”

Hume, chose this name on account of its strikingly massive bill (in Greek megas means great or large and rhunkhos means bill). The Terai habitat in ‘Kaladhunghi’ was previously referred to as the ‘Type locality’ for the Finn’s Weaver.

Post Hume’s discovery, in 1899, Frank Finn, the then Deputy Superintendent of the Indian Museum, Kolkata, obtained two live male weaver birds in yellow breeding plumage from W. Rutledge of Entally. A live animal trader from Kolkata with over 40 years’ experience, Mr. Rutledge had never seen this kind of a bird before procuring the two specimens from Nainital. Finn considered these two birds to be the undescribed form of Ploceus and named them Ploceus rutledgii and briefly described the species as similar to the male of P. baya in breeding plumage, but easily distinguishable by the larger size and the entirely yellow under-surface. As time passed, these weavers, which had been kept alive in captivity, began to change colour (non-breeding plumage), and resembled the corresponding phase of the Baya Weaver. Their colour was however darker and more uniform than the Baya Weaver, and closely corresponded with that of Hume’s bird. Finn noticed that their great size also resembled P. megarhynchus and concluded that Hume’s megarhynchus individuals were a valid species, easily distinguishable from all other Indian forms of Ploceus by the yellow colouration in summer plumage, and to a less extent by their more uniformly ‘stinted’ winter dress. The species was named as Finn’s Baya based on Frank Finn’s discovery of the weaver in breeding plumage.

An illustration by Joseph Smit of a male Finn’s Weaver in nuptial (breeding) plumage and eclipse (non-breeding) plumage.

Curiously enough, during the next 60-odd years, prior to Sálim Ali’s rediscovery of the bird species in the Kumaon Terai in 1959, nothing further was added to our knowledge except for the discovery of a breeding colony in the Bhutan Duars. In 1912, another ornithologist V. O’Donel found a breeding colony in Hasimara, Jalpaiguri district of West Bengal.

Although Humayun Abdulali examined and reported the appearance of the species in Kolkata and Mumbai bird markets occasionally, nothing was known about the exact locations of the species in the wild. Dr. Sálim Ali felt that a well-organised effort should be made to discover it. However, a special expedition to Kaladhungi in 1934 failed. In September 1954, Sálim Ali, with Horace Alexander, made one more fruitless quest around Terai; the same year in June, Mr. Alexander had presumably seen 12 to 15 birds around Bilaspur (Rampur District, Uttar Pradesh) where professional bird catchers distinguished a larger ‘Pahari Baya’ from the other three Indian weaver birds.

Sálim Ali and John Hurrell Crook made a third expedition to Rampur and Haldwani districts of Kumaon in Uttarakhand between July 10 and August 8, 1959, when the Finn’s Weaver was rediscovered breeding in the wild around Rudrapur in Udham Singh Nagar district and its surrounding areas. The species was then studied from 1961 to 1963, by Dr. V. C. Ambedkar. More breeding colonies of the Finn’s Weaver were discovered near Kolkata, West Bengal in 1967 and in 1976 in Darrang district in Assam and in Meerut, Uttar Pradesh in 1979. This species has also been sighted and reported breeding from some Protected Areas of Assam in recent years.

In May 1996, following the bird’s discovery in India in 1866, this weaver once presumed endemic to India, was recorded from Nepal’s Shuklaphanta National Park by Dr. H. S. Baral.

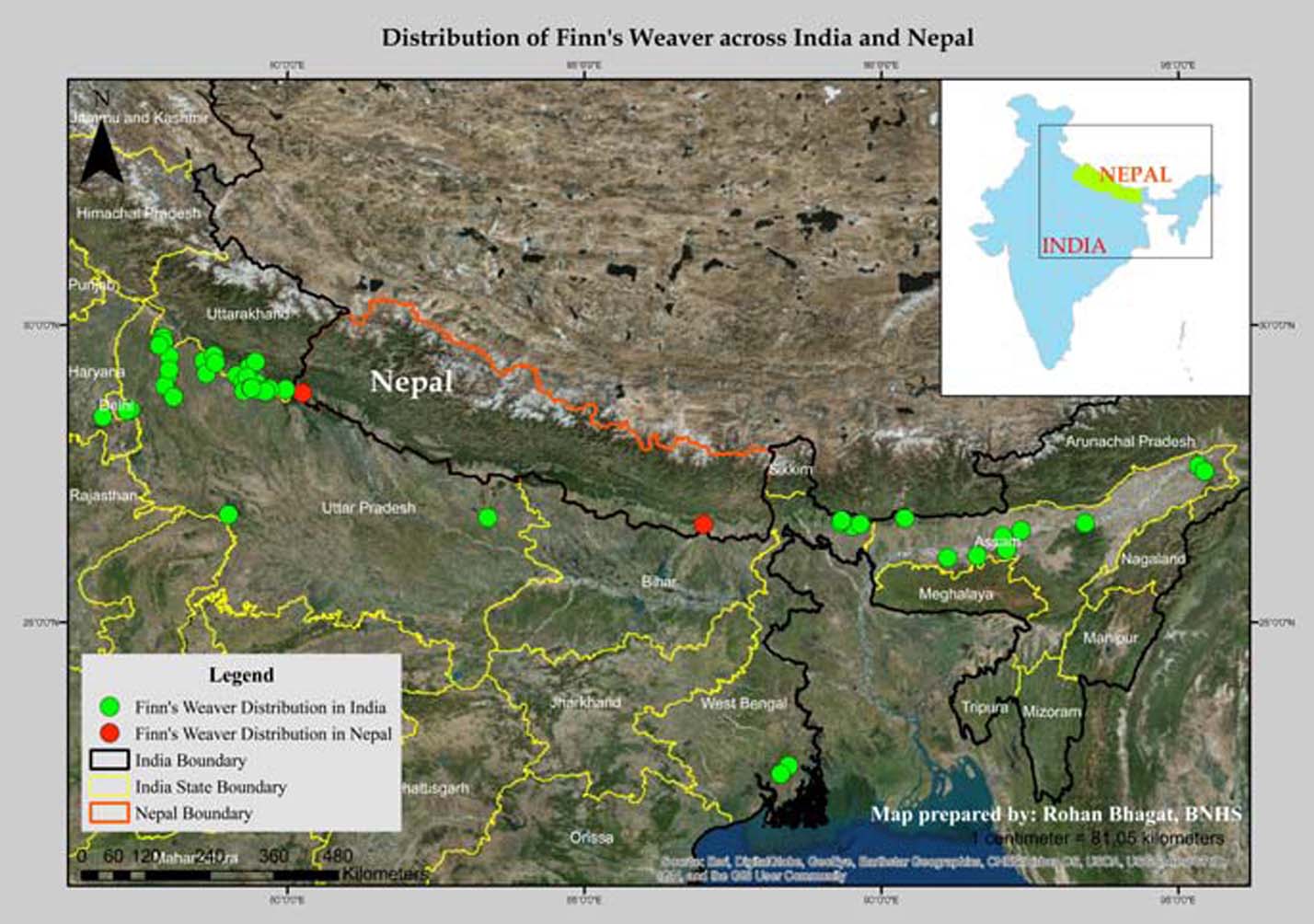

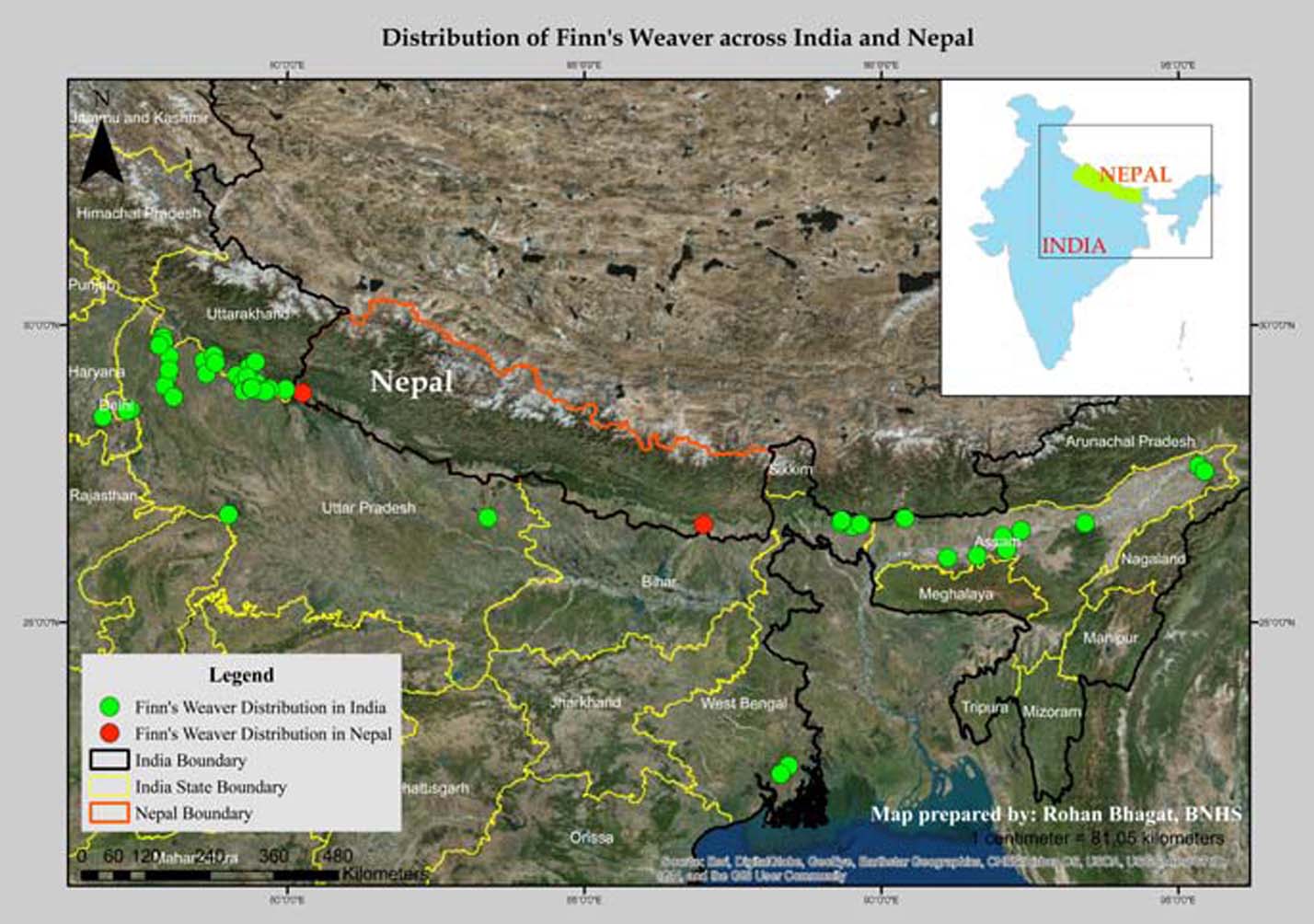

A map showing the distribution of the Finn’s Weaver across India and Nepal, with maximum occurence observed near the border of Uttarakhand and Uttar Pradesh, followed by Assam and Sikkim.

My rendezvous

Ironically, my tryst with the Finn’s Weaver began in my backyard in Meerut. The city was an important bird export centre prior to the blanket ban on domestic trade and trapping of wild native birds in 1990-91. Some Baheliyas infrequently caught and brought the Finn’s Weaver from the Khadhar areas (floodplains) of Haridwar, Muzaffarnagar and Meerut. At one time, the Baheliyas had a footprint all over the Terai, including the Himalayan foothills and Gangetic plains and some of these bird trappers were unparalleled in their field knowledge about birds.

My interest in the species began in 1985, when as an aviculturist, I kept a few for almost two-three years. It was only in 1991, when I joined a Master’s programme in Wildlife Science at the Aligarh Muslim University, that I learnt how rare it was from my ornithology teacher Dr. Asad R. Rahmani. Purely for academic interest, I began collecting all existing literature on the Finn’s Weaver.

Access to old bird traders who transported this species from Uttar Pradesh/ Uttarakhand to Kolkata and Mumbai bird markets were a vital source of information for me. The publication of Finn’s Weaver reported from Hastinapur Wildlife Sanctuary in Meerut by Y. M. Rai in 1979 was another story that kept me searching for the bird around my district. Throughout the 1980s, I regularly observed Finn’s Weavers (up to 40–50 birds each year) near my house. They were brought to Meerut along with other weaver birds for export, mostly from Udham Singh Nagar, and some from around Hastinapur in Meerut.

I began my field surveys on the species from 1997, when I revisited areas in Udham Singh Nagar and located the birds some 40 years after Dr. Sálim Ali’s rediscovery. Again in 2002 and 2003, on an IBA/BNHS funded study, I visited Uttarakhand and Uttar Pradesh where the species still existed in fair numbers. I also visited Manas and Kaziranga. More recently, post 2012, I failed to locate nesting birds at Udham Singh Nagar. One of their key habitats, Rudrapur and its surrounding blocks, had been transformed into a concrete jungle when Uttarakhand was carved out from Uttar Pradesh.

Such mixed flocks of weaver birds are now an uncommon sight. Photo: Rajat Bhargava.

Specific findings

While BirdLife International in 2001 mentions 17 locations of Finn’s Weaver in India based on records from 1866–2000, the BNHS’ study up to 2017 suggested a much higher number – 47 locations. Five visits between 2012 and 2017 revealed that the Finn’s Weaver is currently present in only nine of those 47 locations, three out of the 14 in Uttarakhand, two out of the 16 in Uttar Pradesh, four out of the nine in Assam, and none from the seven in West Bengal or the single location in Haryana.

Of the nine locations where it is currently sighted, three were newly identified during the one-year BNHS survey in 2016–2017, based on information provided by former bird trappers. This includes the Haripura Dam in Uttarakhand, and the Harewali Dam and Bhagwanpur Raini in Uttar Pradesh. Of these nine locations, the western subspecies Ploceus megarhynchus was recorded from five areas, all of which are unprotected. The eastern subspecies Ploceus megarhynchus salimalii is presently found in four Protected Areas in the Northeast, with Kaziranga undoubtedly the best place to see the Finn’s Weaver in India.

Repeat surveys in and around Udham Singh Nagar district reveal a decline from 220 birds and 268 nests in 14 colonies in 2002, to 35 birds and 11 nests in only one colony in 2017. Depending on whether nests or individuals are used as the key metric, this shows a drastic decline of 84.1– 95.8 per cent over 15 years. The BNHS estimates a global population of less than 1,000 Finn’s Weavers, with about 500 adult birds in India.

Of the 124 weaver bird species worldwide, the Black-breasted Weaver Ploceus benghalensis, Streaked Weaver Ploceus manyar, Baya Weaver Ploceus philippinus and Finn’s Weaver Ploceus megarhynchus are found in the Indian subcontinent. Weaver birds are largely granivorous, with adults feeding on seeds, supplemented with invertebrates, although their young are chiefly fed on invertebrates. They inhabit grasslands, marshes, cultivation and very open woodland and are extremely gregarious birds in all seasons, roosting and nesting communally. Known for their excellent nest-weaving skills, males weave elaborate roofed nests with entrance tunnels during the monsoons. Their nest is a vertical oval structure woven with coarse grass strips placed in reeds, suspended from a branch or woven into branches (depending on the species) with a side opening. All weaver birds have a breeding and non-breeding plumage. The males acquire a distinctive breeding plumage with a yellow crown, head and breast ornamentation.

Threats and causes of declines

This species has a small, rapidly declining and severely fragmented population, primarily because of grassland habitat destruction over the last 70 years together with other land use pattern changes in most non-protected sites. Rudrapur, which hosted one of the world’s best Finn’s Weaver populations almost a decade ago, is now transformed into the State Industrial Development Corporation of Uttarakhand Limited (SIDCUL). What you will see in Rudrapur today are government offices, the secretariat, five-star hotels, malls and residential colonies. Industrial effluent polluted swamps, monoculture plantations of commercial trees, booming livestock populations and overexploitation of grasslands continue to adversely impact the birds.

Another reason for the decline is the predation by crows on nesting colonies.The rising population of crows (related to development pressures with increase of garbage and human habitations) could be the reason for unsuccessful breeding. The eggs and nestlings in the globular nest of the Finn’s Weaver on treetops are more accessible to predators, when compared to nests of the other three Indian weaver birds, which build suspended tube-like nests that are harder to raid.

Unlike the three other Indian weaver birds, which build suspended tube-like nests, Finn’s Weavers build a globular nest on treetops, which are unfortunately easier for predators, such as crows. This is the biggest threat to their survival. While the Finn’s Weaver’s population has reached a bottleneck, the crow population is escalating with the ever-increasing human habitation and garbage. Photo: Rajat Bhargava.

Can something be done to arrest the decline of avians such as the Finn’s Weaver? Undoubtedly yes, provided we understand the connection between biodiversity protection, ecosystem health and the quality of human life. To begin with, State Governments need to formulate, draft and implement a ‘state-specific Finn’s Weaver recovery plan’ to restore existing grassland habitats. Needless to add, this will benefit all grassland species ranging from soil microflora, insects, reptiles, amphibians, birds and mammals. On its part, the Central Government should initiate a full-fledged study on the Finn’s Weaver ecology, current status and threats so conservation breeding of the species can begin. The issue of crow predation is also crucial and is probably the easiest to address without waiting for long-term plans to fructify.

Clearly, this species must be uplisted from its Vulnerable status to Critically Endangered category. Campaigns at local, national and international levels would help greatly. I find it ironic that such an elusive and seldom-seen bird, the epitome of Terai grasslands should live surrounded by millions of people, who are barely aware of its presence. As with the recent Great Indian Bustard campaign catalysed by the Sanctuary Nature Foundation, it’s time for conservation organisations around the world to remove the veil of anonymity from the Finn’s Weaver to prevent it from vanishing unmourned.

The author would like to thank Dr. Deepak Apte, M. R. Maithreyi, Dr. Girish Jathar, Gopi Naidu and Rohan Bhagat.