Kaliru

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 42

No. 2,

February 2022

Reviewed by Abinaya Kalyanasundaram

On a summer night in June 2020, firecrackers and Forest Department sirens rip through the air in Mettupalayam town. A jeering crowd chases after a male tusker, pelting fire, sticks and stones. Known as Bahubali by locals, the traumatised tusker flees across coconut plantations and open roads, attempting to climb fences, even as he shrieks in fear, tail and trunk upright.

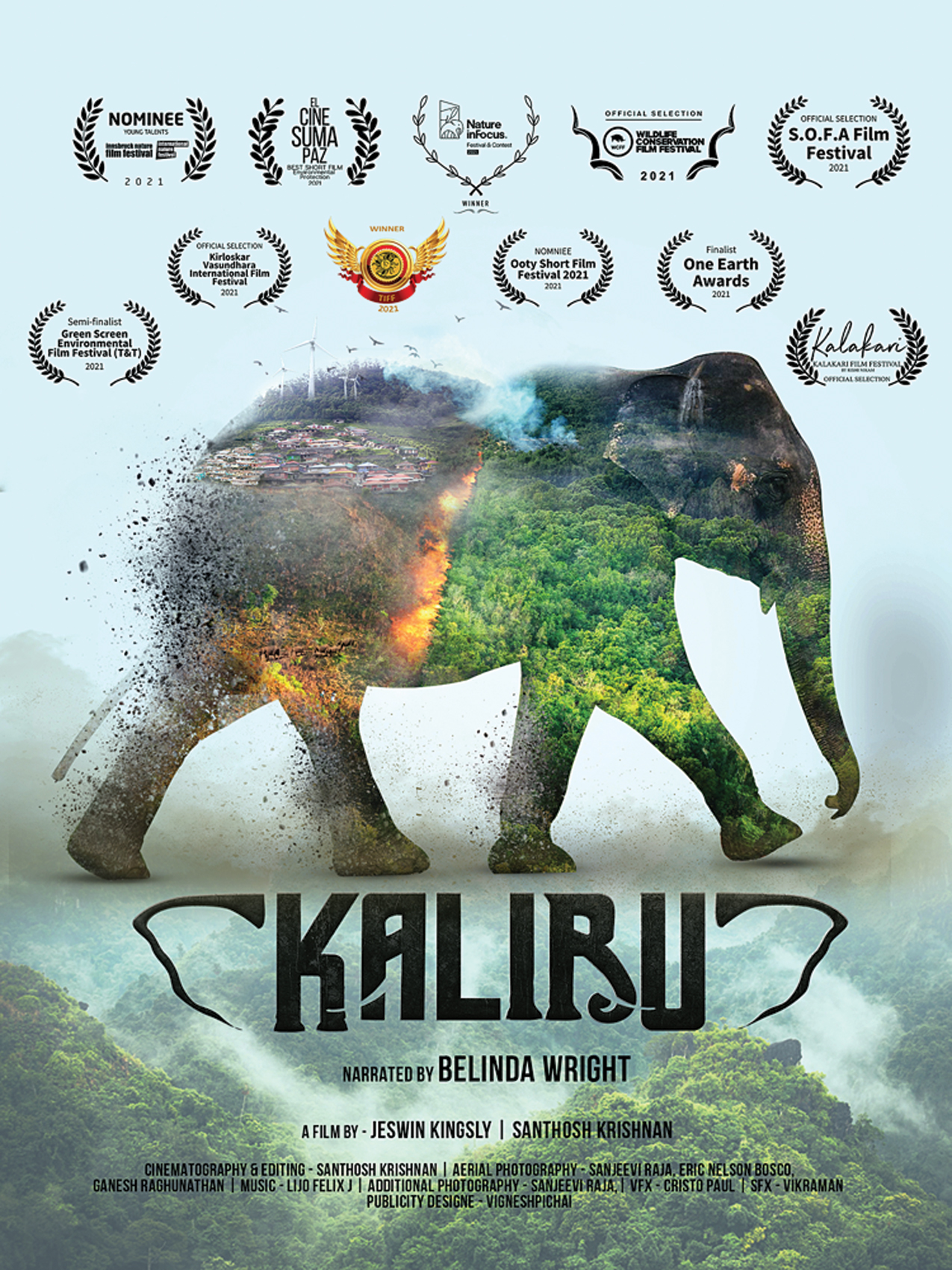

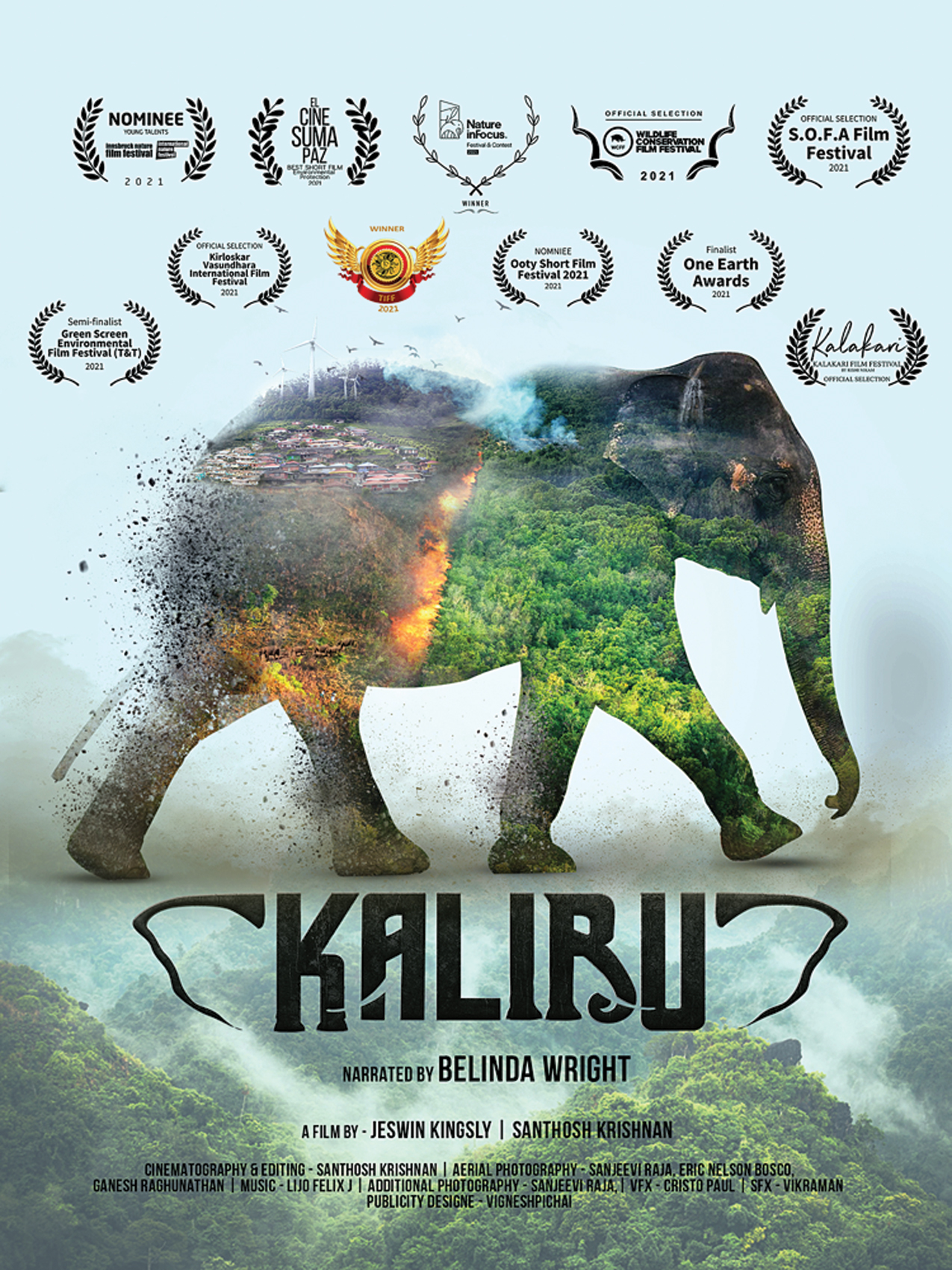

Kaliru released to a global audience in January 2022, on Felis Creations’ YouTube channel. During its circuit of film festivals, Kaliru bagged several national and international awards including the prestigious El Cine Suma Paz, Colombia (Best Environmental Film) and Nature InFocus, India (Winner - Emerging Talents in Conservation), to name a few.

The opening scene of Kaliru, I’m told by film director Jeswin Kingsly, is a relatively common and terrifying occurrence in the towns of Valparai, Mettupalayam, and around Coimbatore district. As human habitations expand into forests, blocking centuries-old migratory elephant paths, the pachyderms are forced to cross through farms and towns. Conflict is an inevitable result.

Kaliru manages to cover the tumultuous relationship between humans and elephants. We catch a glimpse of humanity’s love for Elephas maximus in the prehistoric art paintings in Kumuthipathi, seventh century rock carvings in Mahabalipuram, and large, adorned idols of Ganesha. And we also see the devastating impacts of human action – elephants injured or killed on account of accidental electrocution, poisoning and harassment, and humans suffering injury and, in some cases, even death. Cleverly interspersed with awareness messages conveyed through bommallattam (a puppet storytelling technique common in regional Tamil Nadu), aerial vistas that show beautiful forests contrasting with plantations and buildings, and optimistic solutions being ideated by the Forest Department and NGOs in the region – Kaliru packs a lot in just under 18 minutes.

As human habitations encroach upon ancient elephant migratory pathways, the pachyderms are forced to walk through towns and plantations, where they get accustomed to feeding on bananas and other produce. Photo: Aneesh Sankarankutty.

For a debut wildlife film, Jeswin Kingsly (marine engineer-turned-Head Naturalist at Kipling Camp, Kanha), and Santhosh Krishnan (mechanical engineer-turned-filmmaker and working in Felis Creations), natives of Mettupalayam and Tiruppur respectively, have done a remarkable job. Kaliru is a nuanced, homegrown and honest film that balances authenticity and poignancy without being melodramatic. Perhaps it is this that makes Kaliru so appealing to viewers and critics alike.