Manas Magic

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 26

No. 2,

February 2006

Text and Photographs by Joanna Van Gruisen

A long-time Manas aficionado, the author revisits this Assamese World Heritage Site on the occasion of its centenary celebrations and returns with memories and hope for the future.

One of my most enduring and delightful memories of Manas is of a winter float down the river in a wooden boat. It epitomised the diversity and beauty of this magical area; every moment presented new feasts for the senses.

Immediately, the water birds impress – the migratory ducks, mergansers and the Brahminy with its distinctive soul-touching call. Wintering ibisbills, greenshanks, sandpipers and other waders feed along the waters’ edge while a stunning contrast of black and white fly past – a large skein of cormorants followed eagerly by a flock of little egrets, moving upstream to a new feeding area. Groups of the rare golden langur and a troop of macaques may be spied in the forest canopy to the north and as the river bends south on the eastern bank with its grasslands, hog deer could be seen feeding. In the quiet pools of a side channel, a pair of wild boar wade to feed on the algae, a favourite also of the buffaloes that feed with heads and widespread horns submerged beneath the water surface. Further down, another buffalo herd rests on an open pebble island. The lap of water on our boat disturbs a tiger, watching the herd from behind a small crest. He leaps up in surprise, galloping along the sandy bank before plunging into the water with a mighty splash to swim across the stream and disappear in the long grass. Awed, we float on slowly with the current.

The breakdown of law and order in the 1990s resulted in massive tree felling in Manas, which seriously affected species such as the capped langur that depend on the dense forest canopies.

An Osprey surveys the water from a high perch and on the opposite bank, yellow markings glisten in the afternoon sun to reveal a large water monitor basking beneath the roots of a young simul tree, tenuously maintaining its hold against the river’s erosion. The monitor lizard disappears into a hole, which we pause to inspect, until distracted by a herd of elephants emerging from the grassland upstream. The adults suck up the clear water to slake their thirst and spray their sun-beaten bodies, while the playful babies enjoy their water games, beating the surface with splashes and throwing themselves amongst the legs of their protectively bunched mothers. As the herd moves in single file across the channels, a large tusker takes his turn at the water before following the matriarchal group. We drift on, stopping for the night to camp on a small sand and stone island, opposite an otters’ holt outside which we see their tracks and spraints. We wait hopefully. A sambar hind appears from a patch of forest, submerging herself in the river, to escape bothersome insects, perhaps. The swift current carries her down until she finds a foothold and steps out to stand motionless, drying in the last of the day’s sun. A dainty barking deer steps nervously down for an evening drink. After two hours, our wait is rewarded – the breaking surface of the water reveals five otters returning to the holt. En route they pause to cavort in the water, diving and surfacing in ever-changing patterns; they emerge from the water to run after each other along a fallen tree trunk before diving once again into its depths. Play ends at dusk and they disappear into the bank.

The sun descends: an orange globe reflecting burnt-gold ripples in the water. The pebble islands erupt with a chorus of ‘peeps’ as a shower of pratincoles lift to wheel and turn before diving and darting with sickening speed to catch insects above the water’s surface. The stars appear and the moon rises beyond the Bhutan hills; a greenshank calls and the cry echoes in the gathering darkness.

The unique location of Manas at the confluence of the Indian, Ethiopian and Indo-Chinese realm makes it a treasure trove of biodiversity that includes delicate creatures such as the hoary-bellied squirrel and the only viable population of the smallest and rarest wild suid, the pygmy hog (above) and of course, the elephant, rhino and wild buffalo.

Much of this still remains – in 2005, encouraging signs of otter, leopard and buffalo could still be seen in the mud along the river’s edge – so it is lovely to think that others may still be able to enjoy Manas’ magic as I once did.

‘Know Manas, Love Manas, Save Manas’ – this was the slogan for the centenary celebrations that were recently held in the Manas Tiger Reserve. Hundreds, possibly even thousands, of people walked, biked and drove to Bansbari in Assam to participate and at least approach step one! It was an exciting occasion with much hope and goodwill in the air. After more than one and a half decades of strife and conflict, for those of us who already loved Manas and at times feared that it may not survive, it was a turning point.

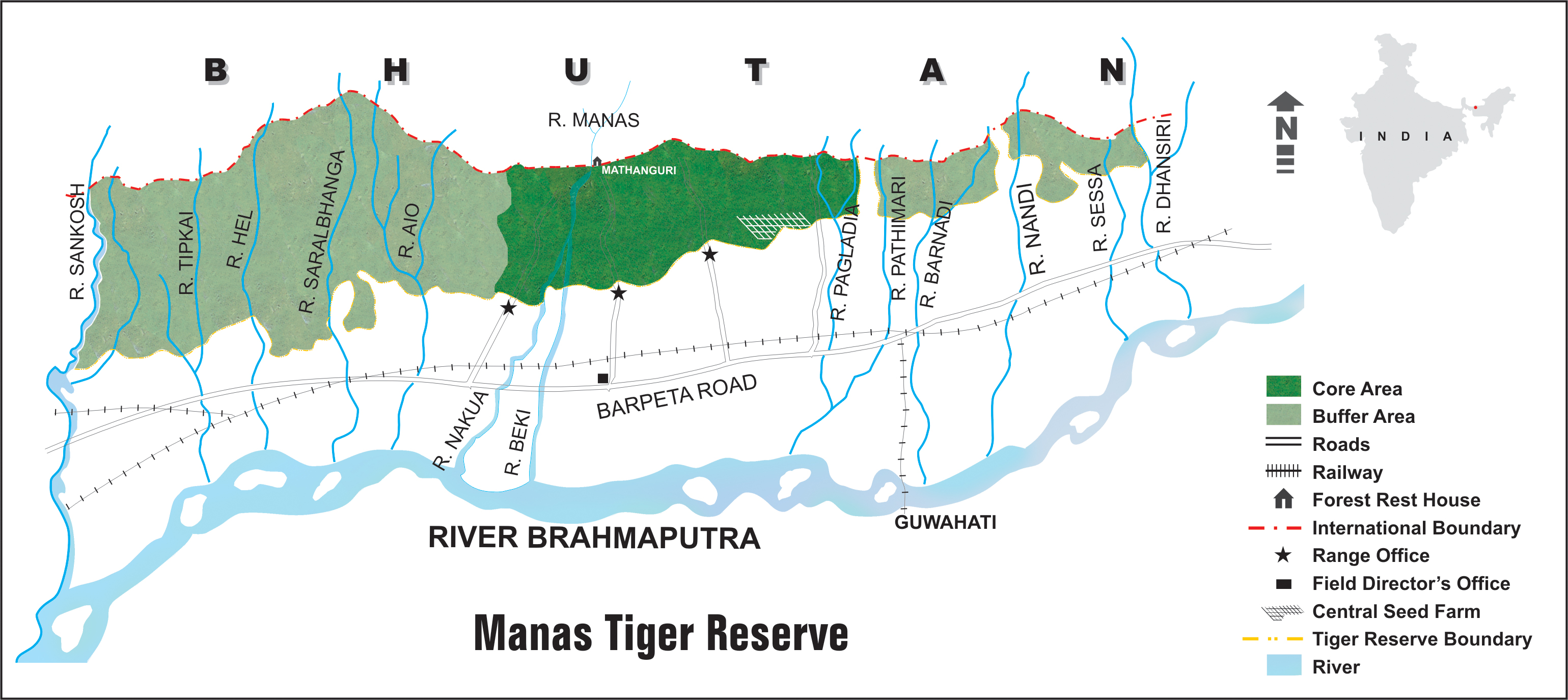

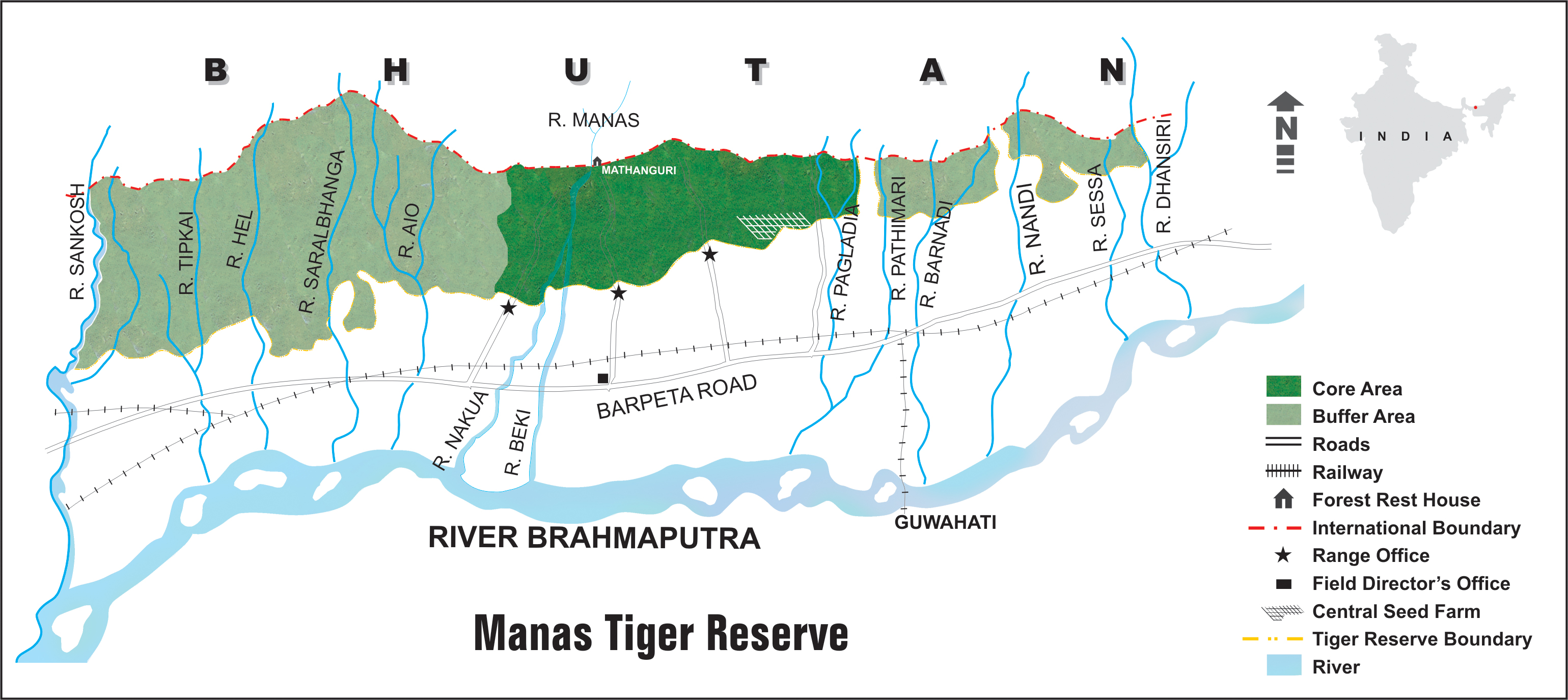

Manas is at an interesting juncture, geographically and politically; the area is protected on both sides of the India-Bhutan border and the national park is situated within the newly formed Baksa and Chirang districts of the Bodoland Territorial Council (BTC). This means that, within India, the Forest Department and the BTC will be working in tandem to bring Manas back from the brink. If they can establish a good equation to do this, it could provide a blueprint for forest departments and communities to work together to conserve other Indian parks. This will not be an easy task but there are admirable individuals from both camps who inspire optimism; if it can work, then now is the time and Manas is the place.

Already a number of poachers have been persuaded to hand over their guns and turn protectors and the celebrations saw several more doing so. It is shocking to hear the number of highly-endangered species (elephants and tigers amongst them) that they have killed in Manas, but elating to see their change of heart. The patience, persuasiveness and persistence of the Bansbari Range Officer is credited with being the key to this turnaround.

My love of Manas began 20 years ago when I spent 10 months there over a two-year period. Manas was facing a different threat at that time. There were plans for major dams to be built on the Manas and Sankosh rivers as part of a flush-the-Ganges project. Ashish Chandola and I were making a film as part of a campaign to illustrate the disastrous nature of such a project. Fortunately, the plan was scrapped, even before the film was made. These two years, 1985 and 1986, were heyday years for Manas. The ‘father’ of Manas, Sanjay Deb Roy was the Field Director, and under his and the staff’s care, management and protection, the area had reached such a pinnacle that UNESCO declared it a World Heritage Site in 1985.

The late Mr. S. Deb Roy, son Saurav, Esmond Bradley-Martin and Lucy Vigne at Manas in 1986. Deb Roy loved and worked for the protection of Manas to the day he died.

Manas’ rich abundance is now much depleted: the pygmy hog and hispid hare still exist here, but some of the larger mammals have not fared so well: the rhino, swamp deer and chital may have disappeared altogether. Tiger, elephant, buffalo and hog deer populations are believed to have dropped drastically. Poaching was always a threat, both for commerce and meat, and in the chaotic times of the Bodo struggle, the plunder was uncontrollable and has had a major impact on the wildlife populations. It was on account of this and the collapse of the Park’s infrastructure, that UNESCO placed Manas on the ‘World Heritage in Danger’ list in 1992. It is yet to be de-listed. Over these years, large areas of the Park also suffered major timber theft and the important fire management of the grasslands was neglected. However, on the more positive side is the fact that there has been limited permanent encroachment into the Protected Area; so, with time and good management, recovery is a possibility.

Apart from protection from poaching, grassland management is another important priority. Appropriate maintenance of the grassland habitat is particularly essential for the Bengal Florican, one of the 382 bird species of the Park. On my recent brief visit to the Park, the grassland areas looked quite different from my 20-year-old memories – the effect of over-grazing and a less than regular burning regime, perhaps.

The jewel in Project Tiger’s crown in the 1970s and 80s, Manas had a healthy population of tigers then and the protection afforded to the striped predator benefitted more common species, such as the peacock and hog deer (above).

Another major change, but a natural one, was in the Manas river. The river is a key to the reserve’s uniqueness; flowing swift and cold from the Himalaya, it enters the Park through a deep gorge in Bhutan. From this exit at Mathanguri, the internal headquarters of the Indian part of the reserve, it immediately broadens and splits into many channels as it flows through the Park. Each year, with the monsoon flood, these channels move and change, the water eroding banks here and creating new deposits there. These islands and old courses soon sprout small plants and then grasses and are an important habitat, especially for the wild buffalo, which are some of the last truly wild specimens remaining in India. With the grass, shishum and simul saplings may appear and so the forest begins its evolution to flourish until, perhaps decades later, the river again returns to gouge away the land and begin the cycle anew. Returning after two decades, these actions were clearly in view. The river no longer flowed in the same channel as it did in 1985. What used to be the main channel is now dry and the full flow of water runs down the course of the Beki, a channel that has not seen so much continuous water for decades.

It was moving to talk to the large crowd of visitors at Mathanguri during the centenary celebrations; many were from nearby Barpeta Road but were visiting for the first time. It was also encouraging to see students and several NGOs participating in the celebrations and to talk to so many talented and enthusiastic young people dedicated to conserving the area. The huge participation and interest in the celebrations represent enormous potential; but the way forward will not be simple. It also appeared that little had changed for the people living around the sanctuary in the 20 years since I was last there; development and conservation are twin challenges that demand creative thinking and hard work to achieve. We must be grateful to all those, rather too numerous to list here, who are dedicating themselves to this challenge in Manas, for truly it is a site of world heritage whose continued existence will be a valuable bequest to us all.

A Glorious Past

Manas was home to 21 of India’s most endangered species – the largest number for any park in the subcontinent. The Park once harboured one of the world’s highest densities of tigers, as well as a large population of leopards. Uniquely, both wild buffalo and gaur were found in large numbers; there were 95 to 100 rhinos and it was estimated that over 2,000 elephants used the area. A population of nearly 500 swamp deer could be found as well as thousands of hog deer.

It is a reserve with a range of diverse habitats: alluvial grasslands, tropical moist and dry deciduous forests, tropical semi-evergreen forests and wetlands. This multiplicity of habitats is what supports the unique variety of species. The golden langur was also first found and described from this area by the well-known naturalist, E.P. Gee in 1953. The pygmy hog was ‘rediscovered’ here in 1971 and was thriving, along with another extremely rare grassland species, the hispid hare. In 1988, there was an even more recent discovery when the then Range Officer, S.K. Sharma, found an Assam roofed turtle Kachuga sylhetensis. There had been no recent record of this rare turtle in India and Manas had not previously been known to be part of its range.

Originally from the U.K., Joanna Van Gruisen has lived in the Indian subcontinent for over three decades. She is a writer, photographer and conservationist.