Meet Dr. Erach Bharucha

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 43

No. 12,

December 2023

A self effacing stalwart in the field of environmental education and conservation, Doctor Sahab has also been a surgeon, surgery teacher, and hospital administrator! Along the way, he has written several key books about nature, including a set on the Wonders of the Indian Wilderness, a must-have for any wildlife aficionado. He also set up various programmes at the Bharati Vidyapeeth Institute of Environment Education and Research (BVIEER), Pune, and implemented long-standing outreach in village schools in Maharashtra. Jovial and lively, the effervescent Sanctuary Lifetime Service Award 2023 winner spoke with Shatakshi Gawade and Prachi Galange who enjoyed a robust tête-à-tête with him, as he reluctantly shared details of his trailblazing life and his steady march onwards, even at 80, to protect the wild world that he loves with an undying passion.

Your involvement in saving human lives and saving wildlife – both such intense fields – is so inspiring! How did you go from being a surgeon to being a conservationist?

I have had two professions all my life. While I was a surgeon, I was also involved with several conservation organisations. Both my parents were nature and wildlife lovers, so that was a natural inclination for me. I was a teacher in surgery, and I administered at two hospitals in Pune. I did a lot of things at the same time. My systematic approach and thorough work ethic allowed me to multitask. When you’re passionate about something, you do that. But it did come with its own share of challenges. I always had very little time, and very long days.

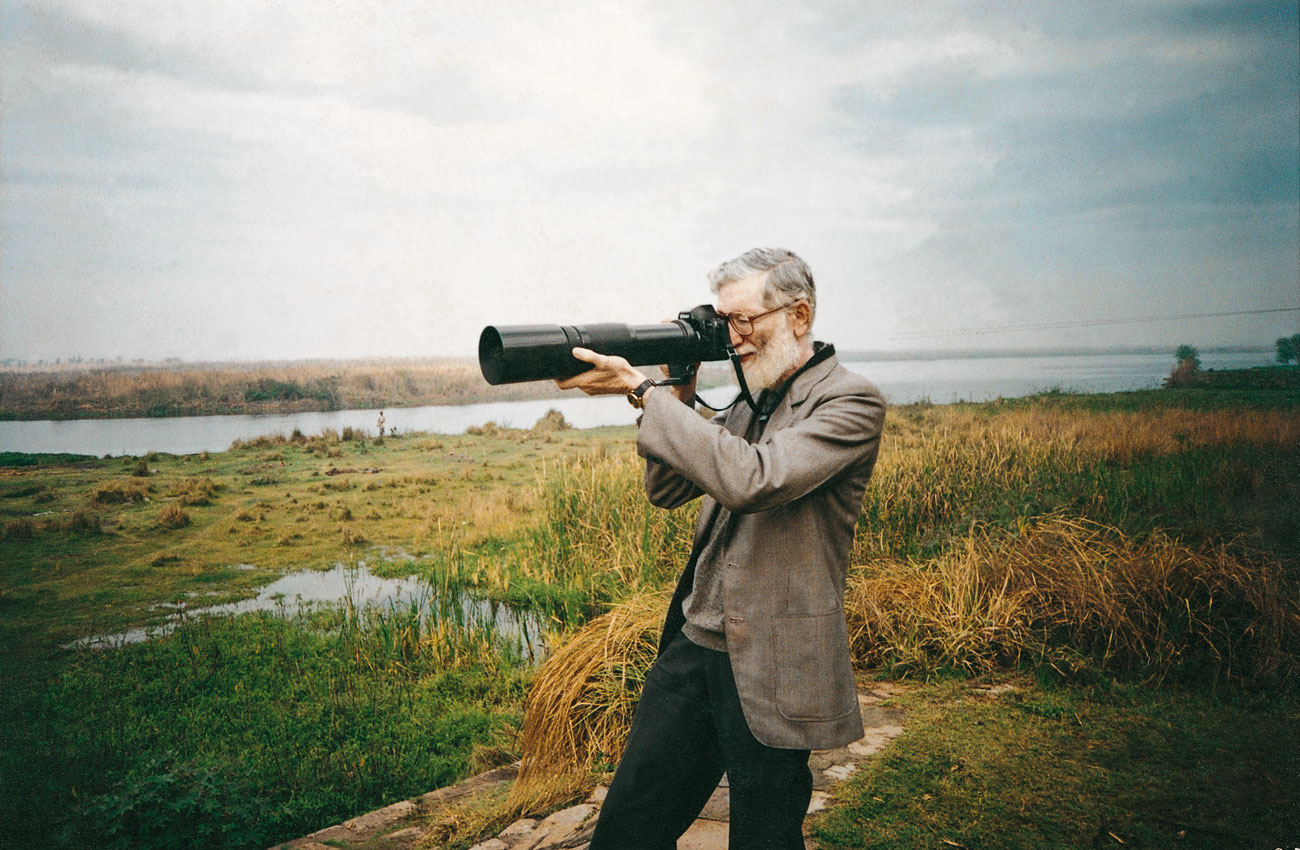

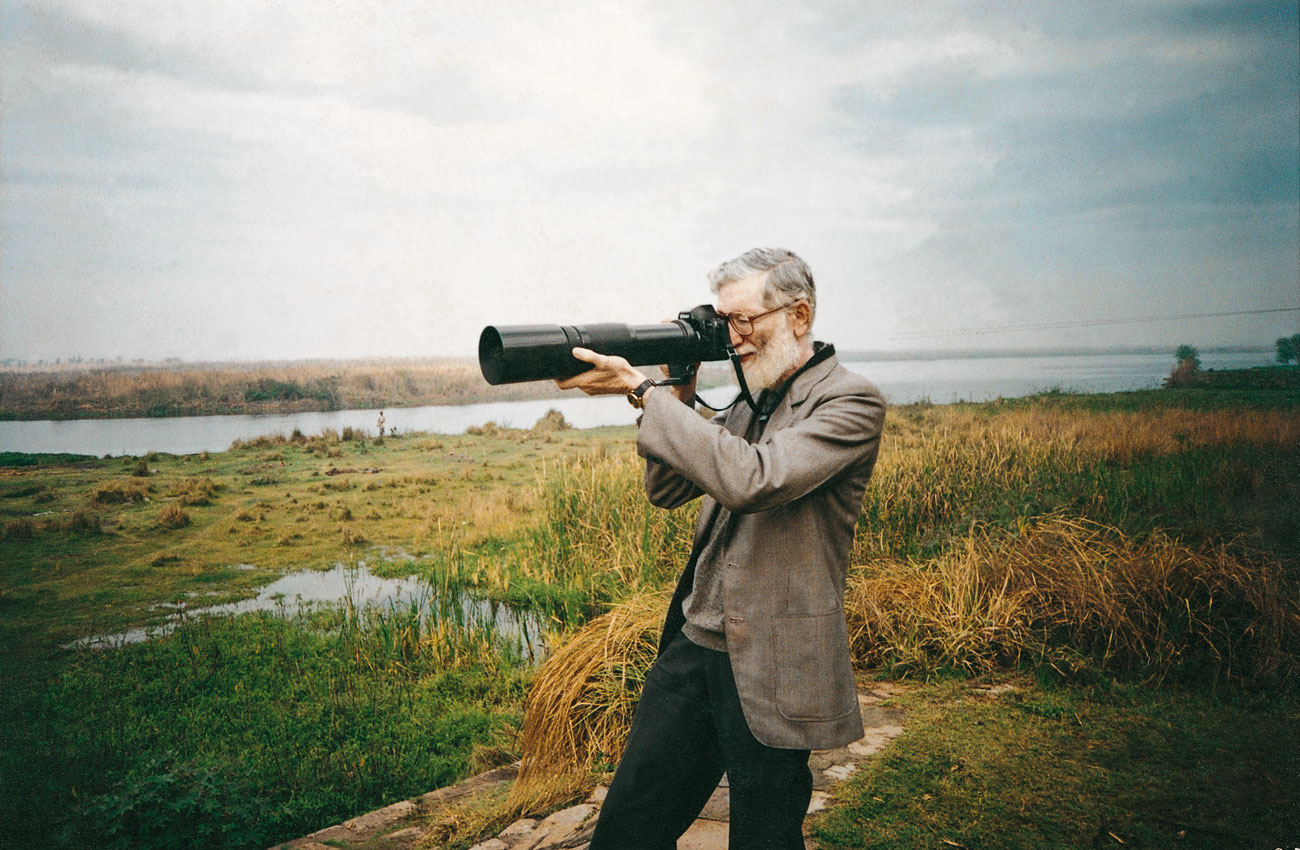

Dr. Erach Bharucha at Bhigwan, photographing flamingos when they first started arriving at the lake 30 years ago. He had a close relationshsip with Dr. Sálim Ali, from whom he absorbed the traits of birdwatching and had his first introduction to nature. Photo Courtesy: Dr. Erach Bharucha.

Who were the people that inspired you in your conservation journey?

There were so many, including stalwarts such as Dr. Sálim Ali, Maharaja of Bansda, J.C. Daniel. Sohrab Pirojsha and Soonuben Godrej, and my BVIEER staff. Each of them played an incredibly important role. As a kid, I rode with Sálim Ali on his motorcycle and he was a key part of what brought me into the conservation fold. The Maharaja of Bansda took me into the Dangs to look for wildlife. J.C. and I explored all the sanctuaries in South India together. Sohrabji Godrej talked to me repeatedly about the importance of sending the message of conservation to children. My BVIEER staff, who are with me for so many years, my students, and the tribal folk that I met across the country over many, many years and who gave me the pleasure of taking photographs and talked to me about their life are all a constant source of inspiration and support. Above all, I owe my deepest gratitude to the rich biodiversity bestowed on our country.

Sálim Ali has shaped the lives of so many, and also the way the environment was studied and taught in India. Tell us how the Birdman of India influenced you.

I had a pair of budgerigars when I was a kid. I was so concerned that they were not laying eggs! Sálim Ali was a family friend, so my father suggested I ask him. He asked me to have patience, and that was one of my first lessons – everything has a time and place in nature. My budgerigars did become parents soon after. Back then, Sálim Ali was studying Baya nesting and would take me to search for new colonies. We built a close bond, a personal relationship, and I only began calling him Sir later at the Bombay Natural History Society, after he asked me to join the committee. The funny thing was he used to call me Doctor Sahab! Though I initially agreed to join the BNHS for a short time, I went on to stay for many years.

From him, I primarily absorbed the traits of birdwatching, and he was responsible for my introduction to nature. A lot of my interactions with him were about what the BNHS did in those days and why it should be done in a certain way. Those were discussions that he had with me many, many times, one on one, long before I officially became a committee member.

There are some sad memories of this time too, because he was ill in the last few years of his life, and I was one of the few people who knew about this. It was traumatic, but his humour was always incredible. I remember how once a government body asked me to use my influence with him to ask for him to speak to some IAS and IFS officers. Given his ill-health, I informed him but added that he shouldn’t feel pressured to come. He immediately quipped, “Dr. Sahab bolenge to karna padta hai (If the doctor says, I will have to do it)!”. He came and gave a delightful talk on flamingos and other birds. He could talk about any subject under the sun! By then he was hard of hearing, like I am now. So, when someone from the audience asked why birds ate crops instead of natural food in the forest, he turned to me and said, “Why don’t you answer that?” I sheepishly replied that I didn’t know and that he was the expert. He stood up and said, “Well, gentlemen, that’s a very good question. I will have to go out and ask the birds!” And he just walked out! He was hilarious!

Dr. Bharucha has focused on grassland ecosystems for a majority of his conservation career. This has included working on blackbucks, Indian wolves, the Great Indian Bustard, flamingos and the rusty spotted cat, with landscape and habitat issues being a focal point. Photo: Surya Ramachandran/Sanctuary Photolibrary.

You have been involved in environmental education for decades. How did you choose academics, when you could have rather been in the forest somewhere?

I didn’t! I’m a conservationist at my core. I love wild places and wildlife. For me, that is most important. But I realised that if I had to spread this message, I would have to spread it through children and the youth.

BVIEER has become a formidable institution over the years. What magic mantra do you give the students for them to stay committed to the planet?

See, most of the students already come with some interest in nature, and that passion has to become a permanent source of inspiration for their lives. This is what we need to transmit, because what we need to do is change their behaviour. They come here with some interest, but most of them go out with an enduring love for nature.

I owe Dr. Patangrao Kadam, the visionary founder of Bharti Vidyapeeth, for having given me the opportunity of initiating and running the BVIEER for several decades. He believed that environment education was a core aspect of school and college education. His faith in my efforts to further conservation education gave me the confidence of spreading the message to our future generation through formal curricular processes.

We run three graduate programmes – Environment Science and Technology, Geoinformatics, which I actually introduced in India, and Wildlife Conservation Action, which we conduct in partnership with the Wildlife Trust of India. We’ve offered diplomas for school teachers, and run environment education, primarily on biodiversity and climate action, in around 45 schools in the Western Ghats, currently funded by the Tata Trust.

Conservation can get really hard, knowing that it takes so long to effect change. How can one sustain this passion and interest?

I think nature itself is sufficient. Humans have a tendency towards biophilia – this innate link that you have with nature, which is triggered by various aspects – like a mentor (for me, it was Sálim), by books, by visuals or even videos. The evolution of visuals for nature is interesting… We began with slideshows, and then came explosive mediums such as the Discovery Channel. Unfortunately, then it was at an international level, and we didn’t have the Indian perspective. This changed with the BNHS’s Hornbill, and Sanctuary magazine. I think Sanctuary played an important part in attracting people to conservation issues. It encouraged mildly interested people to look at nature in detail and change their behaviour accordingly.

Today, behaviour change can’t be brought about through the old nature conservation club systems of 20 students, but it has to happen through the formal education process. Only then will it work, which means training teachers. The problem is that capacity building of teachers is not adequate though fortunately, it is now included in the National Education Policy 2023. You have to take children out, talk to them, have discussions, inculcate critical thinking, and create a behaviour-change approach to learning. We are able to do it because we are a specialised institution. But how many kids and schools can I reach? So, in one way, we failed. We didn’t bring this method in fast enough.

I understand you designed the BVIEER campus! It is such a serene place. Tell us about it.

The flourishing garden in the campus was a dump at one time. We have transplanted some of the trees here. There is a large diversity of bird life, insect life, butterflies here… It’s a caucus of nature in the big campus. A part of the campus area is a water catchment that charges the well downstream!

White-rumped Vultures photographed by Dr. Bharucha at the Mula-Mutha Bird Sanctuary in Maharashtra. The Sanctuary was inaugurated by Dr. Sálim Ali, and is now threatened by road construction. Photo: Dr. Erach Bharucha.

Sanctuary published an article about your work at Bhigwan. What are the other projects that you were involved in?

I’m very much a grassland person. This has included working on the blackbuck, wolf, and the Great Indian Bustard. I also worked on conservation of the flamingo and the rusty spotted cat, focusing on landscape and habitat issues.

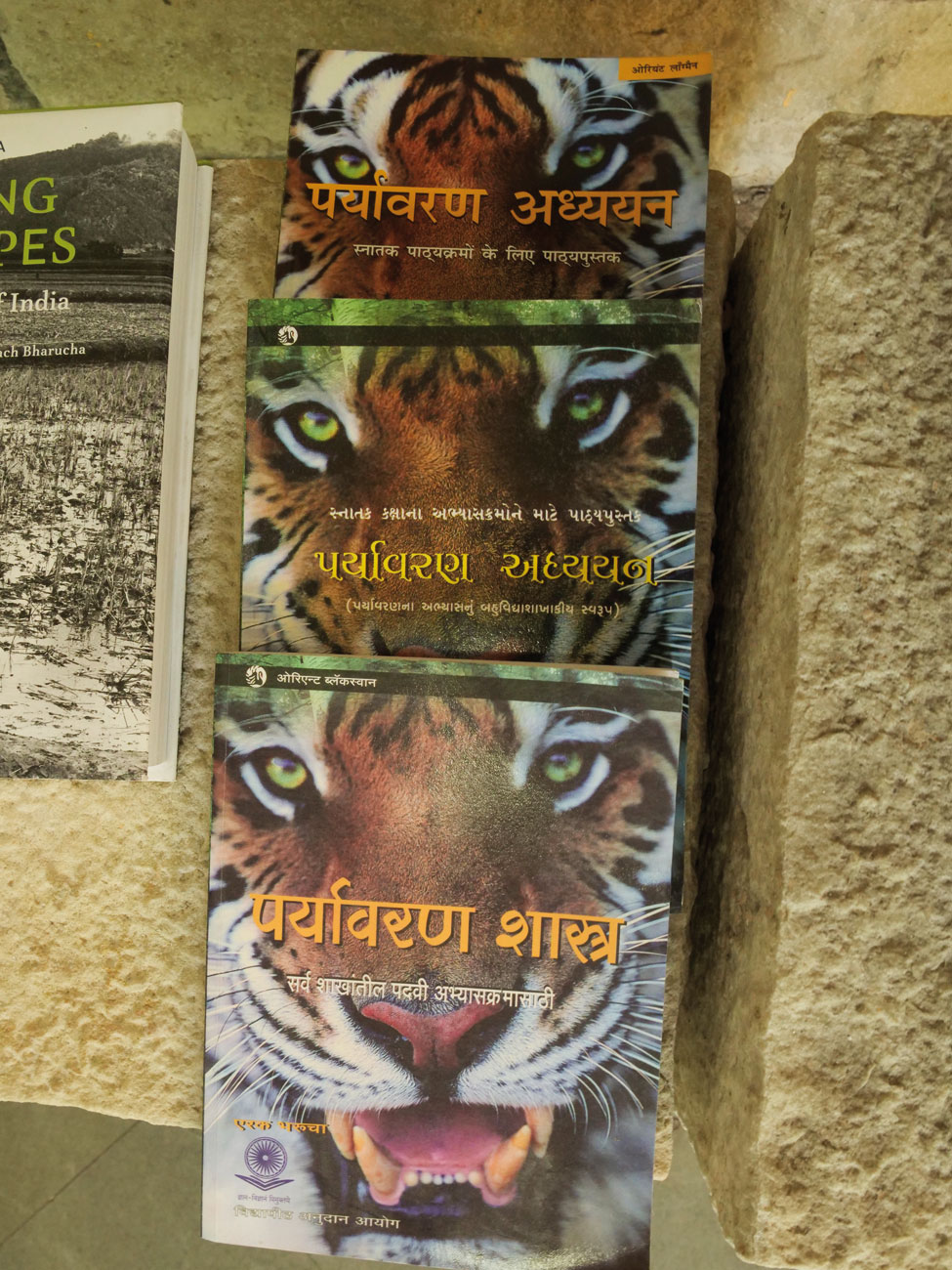

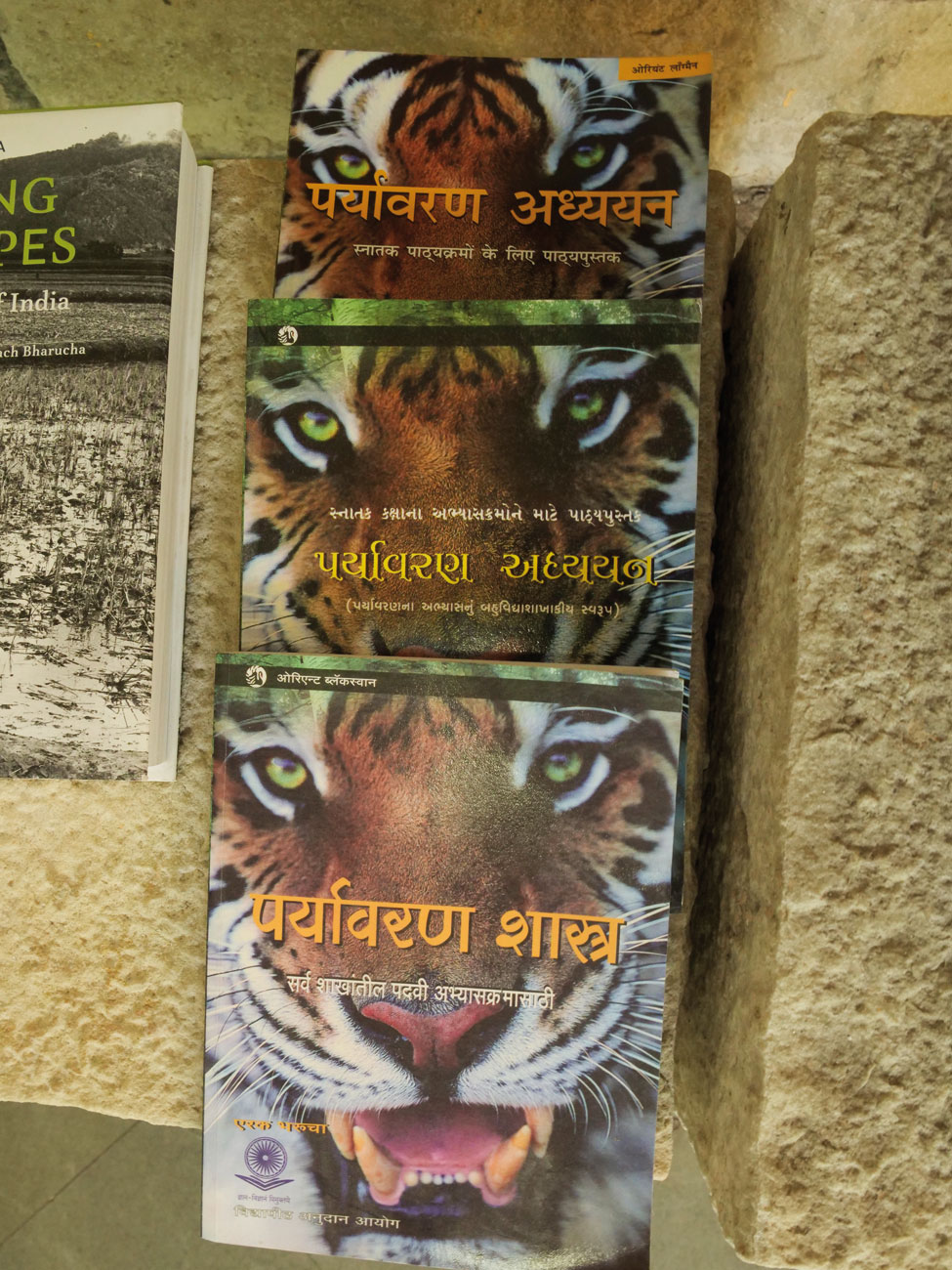

I am happy to have developed the core module course for the University Grants Commission and to have written the first textbook on the environment – Environmental Studies for Undergraduate Courses. It was written in English and translated into seven languages. It is for undergraduates, but surprisingly, it is used by those appearing for the UPSC exam.

BVIEER created a software to analyse 2,000 English and local language books. Based on our study, we changed how the environment was taught, from taxonomy to nature’s processes. We encouraged children to discover nature and link it with what they learnt in their textbooks. This changed how nature education should be done. The Centre for Environment Education (CEE), C. P. R. Environmental Education Centre (CPREEC), and BVIEER all carried this style of environment education forward. Later, we also brought in an understanding of Sustainable Development Goals, and linked them to the formal education process. I brought in biodiversity because I love it, and it is something that every person can appreciate. We are now moving towards climate action and education.

I did an aerial survey of the Dang Forest, and it led to one of the earliest GIS studies on forest fragmentation in India, along with my then student, Dr. Sejal Worah, which then got converted into a GIS programme with Germany. Over the years, I have worked with various organisations – BNHS of course, WWF in the early part in Pune, then WII for years and years, and SACON.

How is it to work so closely with different government bodies?

I’ve never had a problem. I was chairman of the State Biodiversity Board for Maharashtra, the first board was chaired by me. And I worked with the National Biodiversity Authority in various ways. I also was with the government Central Zoo Authority, and I’m currently with the National Tiger Conservation Authority (NTCA). I’ve been well accepted by the Forest Department, especially in Maharashtra, and also at the national

level. They have often listened to what I had to say, whether they implemented it or not.

You mentioned that you initiated geoinformatics in India. How did that come about?

During my trips to the Dang forest with the Maharaja of Bansda, we saw a small cat, but we were not sure if it was a rusty spotted cat. E.P. Gee’s book said it was likely to be extinct. I went to Ranjit Singh, then secretary in the Environment Ministry, and asked for a small budget to look for this cat, with which we could afford one field scientist – the very bright Sejal Worah, one jeep and one driver. We realised we were looking at a very fragmented forest. Work on fragmented forests was new, and nobody had studied corridors, which we tried to map. J.C. Daniel called me and said that there are some scientists in Germany and Italy who wish to do something on geoinformatics. By then I had done an aerial survey and taken photographs of the Dangs’ forest patches. This study became Sejal’s Ph.D. thesis. We identified corridors and changed the boundaries of the Purna Wildlife Sanctuary on those aerial pictures. Changing borders today would be impossible. Nobody knew what GIS was, not J.C., not I, nor anybody in India. We sent the images to Germany and they would come out with maps to tell us about our cat, the tiger, and the corridor pattern. As luck would have it, Sumant Mulgaonkar of Telco (what is now Tata Motors) had the foresight to support our work, and gave Sejal a check to fly to Germany and back. That’s how the first images were produced. That’s how GIS started in India.

And what started your tryst with wildlife photography?

Observing the environment and photographing it went hand in hand for me. I began carrying cameras when travelling around the 1960s. Ah yes… I still think about the wetlands of Ladakh, the landscape of the Western Ghats. All the tribal folk of the Northeast, who interacted with me so much… I really appreciate what I learned about the people of India. That’s where the real India truly lives. Of course, in the midst of all this beauty, I’m hurt by the poverty, the lack of education and healthcare especially.

Was it tough to talk about conservation with those who might not even have basic necessities?

Oh, you don’t need to! They tell you, honestly. If you are empathetic towards them, you learn how to do that. I’ve been welcomed across the wilderness of India. Those books (Wonders of the Indian Wilderness: Three Volume Set) are a testimony to that, especially the last two, Living Bridges and Changing Landscapes. They welcome you to their homes. They have nothing, but they’ll give you tea with milk, which they can’t afford, they will make you a meal. You talk to them about conservation, they already know it. You might have to bring up the fact that you know it is not them, but others who destroy nature, those who have no sensitivity to it.

Dr. Bharucha developed the core module course for the University Grants Commission and wrote the first environment textbook – Environmental Studies for Undergraduate Courses. Written in English, it has been translated into multiple languages, and is even used by students for the UPSC examination. Photo: Prachi Galange/Sanctuary Photolibrary.

BNHS used to sell your CDs of bird songs. How did you produce those fantastic recordings that sold so well?

I was a schoolboy when Brother Nawaro – he was with the BNHS – used to record bird calls in Lonavala and Khandala using a tape recorder with a big spool, and a parabolic mirror with a mic. I would carry the tape recorder on my shoulder for him, the equipment was cumbersome for one person. I thought it was a very fascinating idea, that we could hear those calls back. Later in life, I decided I should do something about these recordings. BNHS also had a list of cassettes recorded by one foreigner. I collected those, got Brother Nawaro’s work and also the large number of bird calls I had recorded across India, and put them all together. That’s how the first cassette came into being. Later, I converted it into a CD on bird calls, long before eBird existed. Those CDs still exist at the BNHS. They were, in some ways, even more useful than the current eBird, because you could hear birds categorised by habitats – grasslands, mountains, and so on.

What would you say is your strength?

That’s a tough one. I think you should ask Bittu, who has known me forever. One of the earliest articles that I ever wrote was in the Sanctuary magazine on Black-winged Stilts on the rivers in Pune. He was excited about the idea that I’m writing about a common bird in the river. And coming back to my strength… It is conservation education. That’s what I love doing most.

In the face of such a grim situation, what keeps you going after all these years? And what is coming up for you next?

I’m very concerned about what is happening, but I believe that one never gives up on conservation, and my love and connectedness for nature keeps me going.

I’m glad you asked about my next work! I’m writing a book on the environmental history of India from the Vedic period to now, and how environmental governance has occurred through different ages. It deals with triggers of environmental issues, such as disasters and international influences; how systems such as NGOs, research and media influence policy making, executive action and judicial issues in the country. I am thoroughly enjoying writing this – this will really be my favourite book!