Meet Dr. Ullas Karanth

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 27

No. 12,

December 2007

One of the worlds foremost authorities on tigers, Dr. Ullas Karanth is a senior conservation scientist and Director of the US-based Wildlife Conservation Societys India Programme. Originally trained as an engineer, he even tried farming before finally homing in on wildlife science as his profession. The central thesis of his work has been the connection between prey and predator numbers and the arena of most of his field work has been Karnataka, particularly Nagarahole, though he has, of course, studied tigers across India. Besides dozens of scientific papers, Karanths popular books ‘A view from the Machan and ‘The way of the tiger have been acclaimed widely. The winner of the Sanctuary-ABN AMRO Lifetime Service Award 2007, he speaks here with Bittu Sahgal about tigers, science and conservation.

Some would say you live a most adventurous life. You must have a host of unforgettable wildlife experiences to share with our readers.

I think darting of tigers from a precarious tree perch, which was well within a tigers leap certainly ranks high in terms of sheer thrill. I will never forget moments like the one from my field diary of 17 years ago: “Then, I spotted the tiger: a brief glimpse of black and sunlit gold. The Randia leaves made a harlequin pattern of light and shade on his body. Padding calmly down a trail, massive head swinging side to side, the tiger was a picture of power and grace… I swung my dart gun around very slowly hoping his keen eyes would not catch the movement… As his shoulder, flanks and, then the right thigh appeared behind the crosshairs, I gently squeezed the trigger…"

Has your life ever been threatened in the course of your work?

Not really. There have been potentially risky moments with elephants while sneaking quietly on transect surveys, or I might have been darting tigers, but I would say I face a greater potential risk by driving on the streets of Bangalore.

How much of an influence on you was your illustrious father, Dr. Shivrama Karanth and what were his views on the wildlife issues so close to your heart?

He was a huge and a very early influence. He was the one who pointed me towards nature. He absolutely loved wildlife and read widely about animals. Our home was, in fact, a haven for all sorts of animals, and I grew up on stacks of nature books and Jim Corbetts tales of man-eaters.

I guess there must have been several other influences from your family.

My ‘aunt Vasantha Satyashankar who gave me my first Sálim Ali book in the 1950s and encouraged me to watch birds; my cousin, senior forester Shyam Sundar who took me to the jungle in the 1960s, and forest ranger and long-time friend since the late 1960s, K.M. Chinnappa, who taught me field craft in Nagarahole. Of course, looming large as an intellectual influence, there was George Schaller, whose work on tigers I read first in 1965 in Life Magazine.

A senior conservation scientist with the New York-based Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) and the Director of its India Programme, Dr. Ullas Karanth, the recipient of the Sanctuary-ABN AMRO Lifetime Service Award 2007, has pioneered reliable tiger population estimation techniques in India and is a role model for many young, conservation-oriented minds. Photo: Julie Maher/WCS.

Where did you actually grow up and where did you complete your schooling, Masters and Doctorate?

I grew up in Puttur, a rural town in the Western Ghats region, 50 km. from Mangalore in Karnataka where I studied in a Kannada-medium school. I then went on to study engineering, and worked for a while. I got to study wildlife formally for my Masters degree in Florida and completed my Doctorate in Mangalore.

What does a day of your job entail?

At one time, my day involved getting up early morning to radio-track tigers. Now, I mostly supervise the work of my younger colleagues or students. I do try to get to the jungle as often as I can… when I do so, I go around checking camera traps set in the forest to photograph tigers and identify them in order to count them…

The photographic capture-recapture method can provide more accurate estimates of tiger densities in a wide array of habitats. Dr. Karanth's achievement in the field of tiger monitoring becomes more significant because he has been able to involve people from all walks of life - engineers, lawyers, activists, naturalists, wildlife connoisseurs and even tribals, in the process of data collection. Photo: Eleanor Briggs.

So would you say the rigors of academia are imperative for sound wildlife conservation action on the ground?

Absolutely, while it is really our hearts and passion that lead us to conservation action, unless we ensure that reason and science guide these, such actions may not deliver effective conservation. As in technology, medicine or agriculture, science has a major role in shaping results and letting us know in real time whether we are on the right track.

And Wildlife First, what prompted you to start and invest time and energy into this organisation?

I am an advisor to rather than an activist of Wildlife First. When a mob of thoughtless locals invaded Nagarahole in 1992 and tried to destroy the wildlife that Mr. Chinnappa (see Sanctuary Vol. XXIV, No. 6, December 2004) had protected for two decades and tried to hamper our efforts to learn through science, I realised that focussed advocacy was necessary to counter such ignorance.

I also saw that most ‘wildlife conservation was confined to big city folks in India. The need to recruit middle class youth from rural and small town areas was essential to break the barriers of class and English language that isolated conservationists from people who made decisions on ground … After all, look at passionate advocates of other interests… women, adivasis, farmers - or at outfits like Maoists, communists or RSS - their core cadres come from this middle India. Now my Wildlife First idea has blossomed in the form of other advocacy groups: Bhadra Wildlife Trust, Kudremukh Wildlife Foundation, Wild Cat-Chikmagalur, Growing Wild and others are some newer examples. Another key element of the Wildlife First philosophy is not just to take ‘action, but take action that is guided by reason and science.

What is the future of tigers in India now that the Forest Rights Act is a reality?

Most breeding tiger populations in India are now confined to some Protected Areas and a few critical habitats - less than 10 per cent of the tigers natural range. It is time to show some generosity towards nature. If the Rules framed under the Forest Rights Act ensure that within critical areas, a policy of fair and adequate relocation and compensation should guide the process of redressing past injustices, tigers can still survive. At least those who claim to have interests of both tigers and people at heart must now focus on this win-win approach rather than go on day-dreaming about painless coexistence of tigers and people in the face of increased forest use, even within remaining critical habitats. Conservationists must never forget that, Act or no Act, every forest dweller is free to move out voluntarily to a better life - no one can stop that.

Of course, there are those who say we dont need tigers or nature anymore and India should be carpeted wall-to-wall with Special Economic Zones (SEZs), sugarcane fields or even tiger farms! I would like to politely differ: as the Earth heats up and becomes less and less habitable, they will, hopefully, change their views.

Much of your work has centered around Nagarahole. What is the current status of the park where most of your early tiger studies took place?

Because of the continuous vigilance of conservation groups that the Wildlife Conservation Society and I are privileged to work with here, in tandem with the efforts of many sincere forest department personnel over the years, Nagarahole is in reasonably good shape. My data shows high tiger densities of 8-15 tigers per 100 square kilometres in the Nagarahole-Bandipur tract. Even more encouragingly, this tiger population is highly productive and able to withstand annual losses of around 20 per cent from mortalities and dispersal…The key to all this is the high prey density of 30 ungulates per square kilometre. I believe Nagarahole exemplifies how civil society groups and scientists can effectively monitor conservation and wildlife, and why such monitoring should not be a bureaucratic monopoly as it is elsewhere in the country.

This is where you put into practice the capture-recapture methodology for tiger estimation. Can you explain this simply for our readers? And what about the pugmark method that so many park managers still swear by?

Capture-recapture sampling is an established, powerful method to ‘catch samples of tigers from populations, in order to estimate numbers without the necessity of being able to ‘catch and count every tiger as the so-called pugmark census demanded. Capture-recapture sampling has intellectual foundations going back to the mathematician, Pierre La Place and has since been developed by some of the best brains in biostatistics like Ken Burnham and Jim Nichols.

The ‘pugmark census was a home grown ad hoc method, which has been hopefully given a decent burial by the Tiger Task Force… I dont think it is worth reviving it, despite the nostalgia on display by officialdom that you talk about. To me the real key to future progress is to allow qualified scientists and institutions to set up projects to rigorously monitor tiger and prey populations in different areas across the country, and abandon the present practice of making tiger monitoring a government monopoly. It surprises me no end that our PM, who takes great pride in abolishing inefficient government monopolies in other fields is actively encouraging such a monopoly in tiger monitoring!

Project Tiger? Success or failure?

Briefly, I would say from the 1970s to late 1980s, it was a qualified success. Since then, the project is in decline and the past few years have seen the worst of this decline. The major problem all through has been lack of science: whether in measuring results or in learning from past successes and failures. The decade-long overall mission-drift in the forest department - away from protection towards wasteful, World Bank style “eco-development" - has also undermined Project Tiger.

Dr. Karanth examining a tranquillised tiger in the Nagarahole National Park, Karnataka moments before radio-collaring the big cat. His study in Nagarahole, which spans over 20 years, has provided us with invaluable insights into both tiger biology and prey-predator relationships. Photo: Fiona Sunquist.

Do you subscribe to the view expressed by so many people that tigers could go extinct by 2010?

Periodically, conservationists have predicted the tigers demise, shifting the “last date" from the 1950s (Jim Corbett), to the end of the last century (Peter Jackson), to 2010 or some other date now. Fortunately for tigers, they keep moving the goal post! I believe tigers will manage to survive in well protected forests, provided dedicated government staff and NGOs are able to find the wisdom to work together. But yes, local extinctions are inevitable where cooperation to save forests and wildlife vanishes: Sariska is a classic example. I do not believe all the worlds wild tigers are going to be extinct any time soon.

What would your first three priorities be if you were given the authority to change wildlife policy in India?

Divert sufficient money from budgets now earmarked for rural development, roads, power transmission (and other sources like CAMPA) to pro-actively promote and implement voluntary resettlement of people now marooned within critical wildlife habitats, in a fair, generous and time-bound manner. However, identification of such critical wildlife habitats must be through a scientific process and not a bureaucratic one, as it is now.

Modernise, educate and economically develop rural areas around our wildlife habitats so that their present dependency on all forms of forest biomass exploitation decreases rather than increases in the long run. Of course, the forest department should not be the agency doing this through “eco-development"!

Put in place a technically-trained management agency (as in engineering and health sectors) in place of the present UPSC-IFS recruitment system. This ‘steel frame model may be okay for IAS, but not for managing land, forests and local people. The personnel at higher levels should only be recruited from within respective states, should have a five-year professional degree in wildlife conservation and preferably be on five-year renewable contracts. All the lower level wildlife positions must be earmarked 100 per cent for tribal and traditional forest groups and other local stakeholders who possess field skills and jungle-craft.

How do we deal with the policy of the government to keep researchers out of the Protected Areas when it disagrees with their findings or their basic positions?

It is NOT government policy to discourage wildlife research. It is the absence of clear and unambiguous directions in the Wildlife (Protection) Act in this regard, which is leading to this problem. The officials are guided by the Act and they dont see wildlife research as a priority in it. The only solution is to put in a set of amendments to the WPA prioritising research that is independent of the managements perceptions and governments own research monopolies. This task of amending the Act should be entrusted to the Ministry of Science and Technology and reputed wildlife scientists if the problem is to be really solved. All attempts of the Ministry of Environment officials to solve this serious problem during the past 10 years have only made the problem worse.

And your MSc. programme at the National Centre for Biological Sciences (NCBS)? How did you come to be involved with this institution?

A few years ago I saw a huge, unfulfilled need for training wildlife biologists to guide future conservation in a mega-diversity country like India that faces myriad problems. My own organisation, Wildlife Conservation Society, agreed to support such a programme, but we did not want to invest funds in buildings, laboratories and what have you, preferring instead to try and harness special technical skills and the manpower necessary to support the programme. We were looking for a partner and contacted NCBS, a part of TIFR and a reputed research institution in cell biology, genetics and related areas. It has a world class campus, labs and faculty in Bangalore. NCBS became a natural ally because its director K. Vijayaraghavan shared our vision.

Do you think conservation education should receive more funds in India?

The problem is not one of just putting in money. There are now too few people who can really teach wildlife subjects. Therefore, the priority task should be to retain our qualified wildlife scientists (and attract them back into the country) and absorb them into the numerous biology, zoology and botany departments in the University system. At present, these departments are all filled with faculty who have no training or focus in wildlife or conservation. Even now, colleges are creating more and more so-called ‘wildlife, ‘environment and ‘conservation departments, but packing them with instructors who are only trained in the traditional laboratory oriented zoology and botany…This is what needs to be changed.

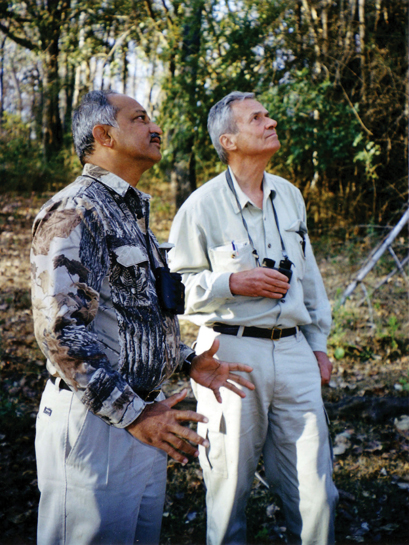

The legendary George Schaller's seminal work on tigers in the mid-1960s greatly influenced Dr. Karanth, who was an avid reader of wildlife and conservation-related literature since his childhood. Photo: Shekar Dattatri.

Any message you would like to pass on to young persons today?

Learn to watch animals and birds, the joy and satisfaction you will get from this will far exceed anything cricket, cinema or rock music can give you! Also, remember that people from all professions, not just wildlife conservationists can act decisively to protect nature. Meet and badger key officials, educate important decision makers and officials, write to the press, file court cases. But be clear that all such action must be based on a clear understanding of the problem and always articulate realistic solutions.

What is the legacy you would like to leave your own children and the children of India?

Legacy is too grand a word to describe what I will leave. A few ideas that work on ground and help to save wildlife at best… In any case, I now think beyond my daughter and granddaughter! If my great-granddaughter sees wild tigers, and if I have played some role in making that happen, I will be happy. In the final analysis, my view is an unapologetically bi-centric one: I am deeply concerned that wildlife and wild lands, which have evolved over millions of years must survive on this planet at least in their present remnant form. I believe that the present generation of humans has no moral right to extirpate wild nature, and that we hold nature in trust for future generations.