Monitoring Trans-Himalayan Migrants in Ladakh

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 41

No. 6,

June 2021

In 2013, Simon Delany received an email from Praveen J., Associate Editor of the journal IndianBIRDS, requesting historic details of bird species he and birder colleagues had recorded in Ladakh as young graduates of Southampton University in the 1970s and 1980s. Over the course of three expeditions, they had documented over 130 species migrating through the region, and individually marked nearly 8,000 birds with rings provided by the Bombay Natural History Society.

Simon Delany and Clive Denby observing migrant swallows and martins brought down by cloudy weather at the Thikse plantation in the upper Indus valley, in the autumn of 1980. Photo: John Norton.

Simon Delany and Clive Denby observing migrant swallows and martins brought down by cloudy weather at the Thikse plantation in the upper Indus valley, in the autumn of 1980. Photo: John Norton.

Expedition Ladakh

I had developed a fascination for migration across the Himalaya after reading Horace Alexander’s Seventy Years of Birdwatching published in 1974. Alexander was a teacher, writer, pacifist and ornithologist who spent many years in India during which he even became friends with Mahatma Gandhi. His book drew attention to the readiness of some migratory birds to follow a direct route to their destination, even over high-altitude barriers. Alexander described how in late May and early June, he had often observed swallows, martins, swifts, warblers and Golden Orioles in the western Himalayan foothills above Dalhousie in Himachal Pradesh, at 2,450 masl., flying directly towards the high ranges.

Alexander’s account somewhat contradicted the magnum opus of Reginald Moreau, The Palearctic-African Bird Migration System, a masterpiece of scholarship published in 1972. This book described how migrant birds breeding in northern Asia avoid the Tibetan-Himalayan region by taking routes to the east and west, and concluded that there was “virtually no evidence” of migration by a significant number of passerines across this extensive high-altitude region.

The Forest Department-run Thikse plantation in 1977, looking south towards the Zangskar Range. The combination of wetland, scrub and low tree habitats on the banks of the Indus river provide an excellent area for migrant birds to rest and feed. Photo: Charles Williams.

The Forest Department-run Thikse plantation in 1977, looking south towards the Zangskar Range. The combination of wetland, scrub and low tree habitats on the banks of the Indus river provide an excellent area for migrant birds to rest and feed. Photo: Charles Williams.

The migrants described by Horace Alexander would have reached Ladakh from Dalhousie with a flight of less than 200 km. across the Great Himalaya. During a preliminary visit to Ladakh in 1976, my friend Clive Denby had recorded migrant waders in the upper Indus valley. It seemed likely that an expedition to Ladakh, adopting an intense and systematic approach to the recording of migrants, would make interesting discoveries. Our 1977 expedition established a migration watchpoint in a Jammu and Kashmir Forestry Department plantation, close to Thikse village in the upper Indus valley, 18 km. from Leh at an altitude of 3,300 masl. We set up our mist nets in the plantation and opened them every morning at dawn during the autumn migration seasons of 1977, 1980 and 1981. We observed and recorded birds throughout the hours of daylight every day, often walking a 10 km. stretch of the valley down to Choglamsar in the afternoons. In 1981, we extended our stay through the winter and continued working through the spring migration season of 1982. Our expeditions were supported by a number of organisations and institutes including the Smithsonian Institute and the British Ecological Society. We produced comprehensive unpublished reports for these funders, but we were unable to obtain funding for formal publication of the results.

Ornithologists (left to right) Keith Godfrey, Simon Delany, Paul Harvey, Clive Denby and John Norton photographed in 1980 on the veranda of the Forestry Department hut that was the expedition base. Photo: John Norton.

Ornithologists (left to right) Keith Godfrey, Simon Delany, Paul Harvey, Clive Denby and John Norton photographed in 1980 on the veranda of the Forestry Department hut that was the expedition base. Photo: John Norton.

Following Avian Migrants

In response to Praveen’s email, I wrote a paper for IndianBIRDS in 2014, which provided details of nine of the 10 species recorded in India for the first time (the 10th, Naumann’s Thrush Turdus naumanni was added in 2017 as a result of a taxonomic split). The nine first records for India were the Lesser Grey Shrike Lanius minor, Great Reed Warbler Acrocephalus arundinaceus, Black-browed Reed Warbler Acrocephalus bistrigiceps, Sedge Warbler Acrocephalus schoenobaenus, Garden Warbler Sylvia borin, Song Thrush Turdus philomelos, Common Redstart Phoenicurus phoenicurus, Eurasian Linnet Linaria cannabina, and Yellowhammer Emberiza citrinella. Most of these species have since been observed elsewhere in India, but our two records of Sedge Warbler remain the only Indian records of this species. Five of the species recorded in India for the first time were migrants that breed in Siberia and winter in Africa, unexpectedly taking a route through the Ladakh trans-Himalaya. Altogether, we found 18 species that breed to the north of the Himalaya and winter in Africa, migrating through Ladakh.

(Left) The two records of Sedge Warbler Acrocephalus schoenobaenus by the author and his team remain the only Indian records of this species to date. Photo: Clare Sulston. (Right) The Güldenstädt’s Redstart Phoenicurus erythrogastrus is a winter visitor to the upper Indus valley in large numbers from breeding sites at high altitudes. Photo: John Norton.

A special feature of the ornithology of Ladakh is the altitudinal migration that brings species that breed at extreme altitudes down into the valleys for the winter. At this time, the Thikse plantation and other valley bottom sites host large numbers of Güldenstädt’s Redstarts Phoenicurus erythrogastrus, Brown Accentors Prunella fulvescens and smaller numbers of other species.

We described the migration patterns of many species, and noted how cloud cover and rain increased the number and diversity of migrants recorded, suggesting that in clear conditions, migrants pass over at high altitude without stopping. We concluded that – as observed by Moreau – a sizeable majority of migrants appear to avoid the Tibetan-Himalayan region, but that a large number of a high diversity of species nevertheless pass through or over the mountain ranges. Trans-Himalayan migration therefore probably takes place on a previously unrecognised scale. To take the example of one group – waders (shorebirds) – we recorded 27 wader species migrating through Ladakh, but only four were seen frequently, namely, in order of abundance, Green Sandpiper Tringa ochropus, Temminck’s Stint Calidris temminckii, Wood Sandpiper Tringa glareola, and Common Greenshank Tringa nebularia. We speculated that a minimum of 1.4 million waders might be passing over the Tibetan-Himalayan region each autumn – a small but nevertheless important proportion of the waders that migrate out of Siberia. These findings have recently been reinforced by the work of David Li and colleagues, who used satellite telemetry to track Common Redshank Tringa totanus and Whimbrel Numenius phaeopus migrating over the Himalaya from their wintering grounds in Singapore.

_1624346440.png)

(Right) This Common Redstart Phoenicurus phoenicurus, the first recorded in India, was trapped and ringed on May 25, 1982. It was on its way to its breeding grounds in the Siberian forests from the wintering area in sub-Saharan Africa. Photo: Charles Williams. (Left) The Common Snipe Gallinago gallinago was recorded occasionally in small numbers at the Thikse plantation. Photo: John Norton.

Conserving Flyways

The world’s bird migration systems have been divided into so-called ‘flyways’ to provide a political and legal framework for international cooperation in the conservation and management of migratory birds. Each flyway comprises the broadly similar migratory routes followed by many different species, and includes all the sites and habitats used by these species throughout the annual cycle. India is the destination of a high proportion of the millions of birds that use the Central Asian Flyway, and the Tibetan-Himalayan region forms a barrier that spans much of the mid-latitude part of this Flyway. The Government of India, as a signatory to the UN Convention on Migratory Species, recognises its responsibility to conserve the Central Asian Flyway migration system. At the 13th Conference of the Parties to the Convention in Gandhinagar in 2020, the Prime Minister of India referred to this responsibility in a keynote address, and implementation of the long-delayed Central Asian Flyway Agreement is keenly anticipated. Nishant Kumar and colleagues recently tracked the high-altitude migration route used by hundreds of thousands of Black-eared Kites Milvus migrans lineatus wintering in Delhi to widespread breeding sites ranging between Kazakhstan and Mongolia. Despite its scale, this migratory route was completely unknown until the study was published in 2020, and this pioneering work drew attention to the urgent need for more research and monitoring on this flyway.

Clare Sulston carefully extracts a bird from a mist net in September 1981. The team installed the nets at Thikse, and would open them at dawn each morning, then check them every half hour. Mist netting is a capture method commonly used by trained scientists studying wild birds and bats, who individually mark and measure their study subjects before quickly releasing them back into the wild. Photo Courtesy: Clare Sulston.

Clare Sulston carefully extracts a bird from a mist net in September 1981. The team installed the nets at Thikse, and would open them at dawn each morning, then check them every half hour. Mist netting is a capture method commonly used by trained scientists studying wild birds and bats, who individually mark and measure their study subjects before quickly releasing them back into the wild. Photo Courtesy: Clare Sulston.

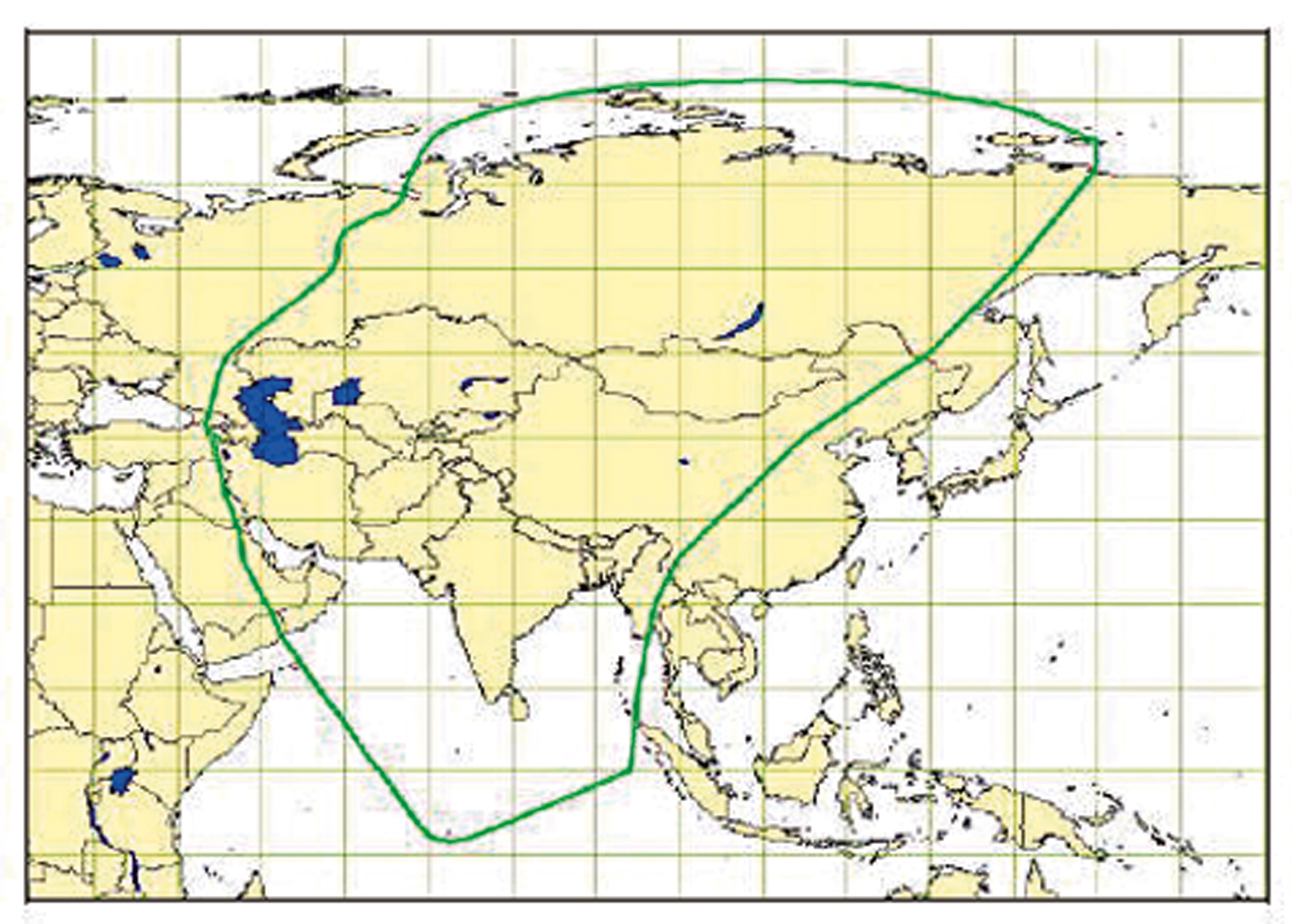

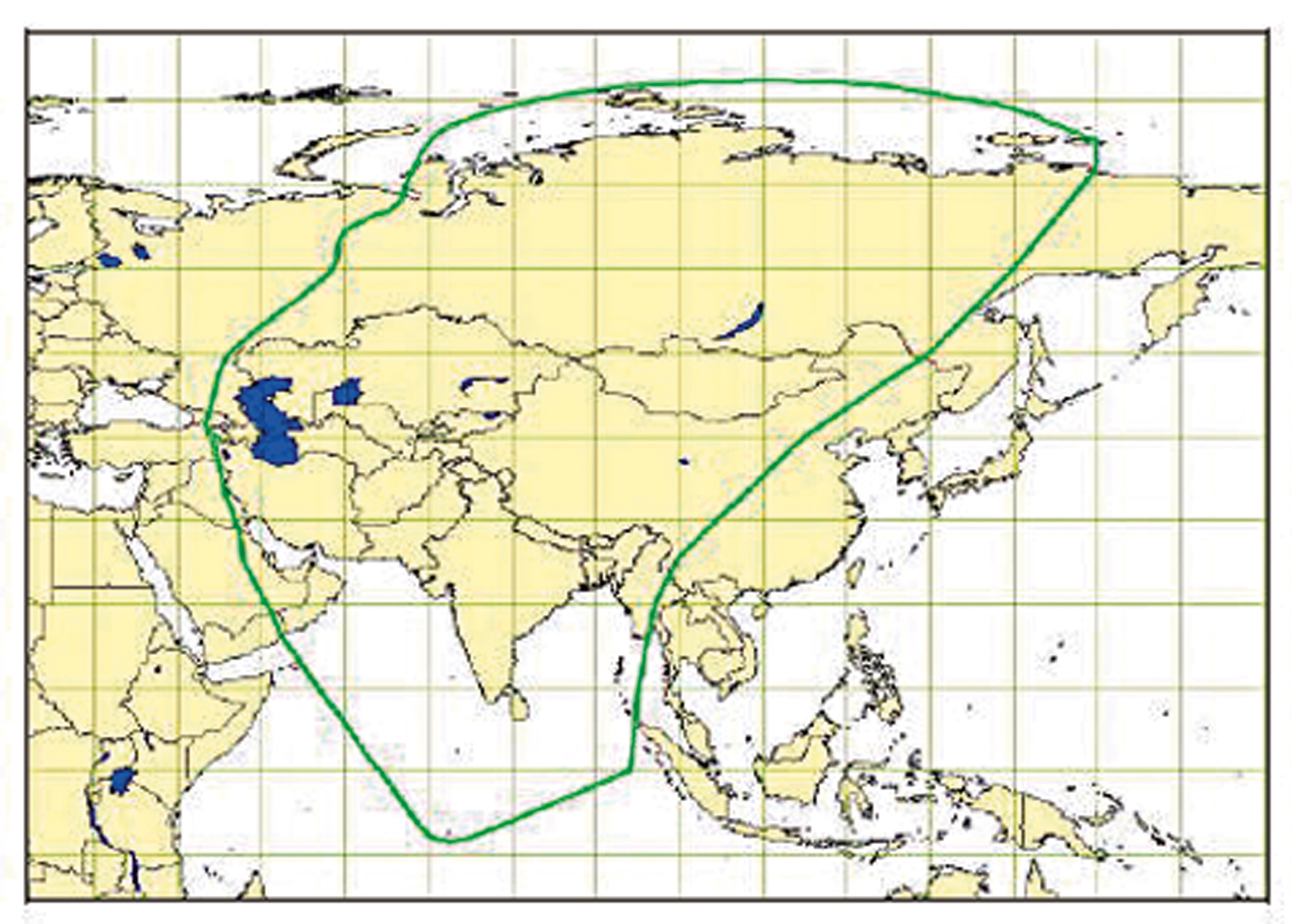

The migratory routes of the Central Asian Flyway begin from northerly breeding grounds across Siberia and extend down to wintering grounds in South and West Asia, on the mainland and neighbouring island chains. Map Source: CAF Action Plan, New Delhi, 2005.

The migratory routes of the Central Asian Flyway begin from northerly breeding grounds across Siberia and extend down to wintering grounds in South and West Asia, on the mainland and neighbouring island chains. Map Source: CAF Action Plan, New Delhi, 2005.

It was wonderful to delve into our archive and review our results for the 2014 IndianBIRDS paper, and contributions to the 2017 book Bird Migration Across the Himalayas, edited by Herbert Prins and Tsewang Namgail. It brought back memories of exciting times in the field, making discoveries in spectacular landscapes with dear friends, and also of the warmth, hospitality and good humour of the Ladakhi people among whom we lived and worked for a total of nearly two years. After the award of the Ph.D. that has been keeping me busy in my spare time for the past seven years, I hope to return to Ladakh to discover how things have changed since our expeditions all those years ago.

Simon Delany is an English ornithologist and environmental consultant living in the Netherlands, he spent his teenage years training as a bird ringer. He is currently finishing a Ph.D. on migration strategies of birds in Ladakh.

_1624346440.png)