Operation Save Kaziranga

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 40

No. 6,

June 2020

By Naveen Pandey and Rohini Ballave Saikia

Krishna Saikia, a villager in Sukanigaon, looked worryingly at the floodwaters bracing the rim of the water outlet of her hand pump. The surging floodwater was engulfing the last remaining potable water source in her village. Her freshly sown rice saplings were under three metres of water as she looked at the aquatic horizon merging with the treeline of the Kaziranga National Park (KNP), some two kilometres behind her thatch-roofed hut. The bamboo grove in her courtyard sheltered half a dozen hog deer, a couple of wild pigs and three swamp deer. She would monitor them and warn anyone who attempted to harm her wild guests. She hoped they would regain their breath to swim further away and cross the highway towards the Karbi hills. Krishna knew she was neither alone in her struggle to stay afloat, nor would this be the last time she faced the flood.

Around 33 high grounds have been built in the park to provide safe refuge for wild animals during peak flood seasons. During floods, large congregations of animals can be found here, all inter-species hostility temporarily forgotten. Photo courtesy: Arun Vignesh

A Seasonal Flood

Hundreds of years of flooding, siltation, and erosion have defined the Kaziranga National Park as a forest-wedged riverine grassland and predominantly shaped the culture and socio-economic matrix of thousands of native inhabitants. Flood management in Kaziranga has its inherent challenges, which call for non-conventional approaches. As people experience the floods, year after year, their perception of it shifts from that of a furious phenomenon to a natural component of the locals’ lives. While the rest of Assam faces floods of a different scale and intensity, flooding in Kaziranga is unique in its arrival, progression, impact, and even its retreat. All the stages of flooding in Kaziranga are graceful, with some pain for the community and escalating stress for the wild animals as access to the natural high lands gets tougher every successive season.

Contrary to popular belief, the preparedness for floods originates beyond the boundaries of the park. The Kaziranga National Park, with its two administrative units – Eastern Assam Wildlife Division and Biswanath Wildlife Division – is spread over 884 sq. km. and it is actively protected by 180 anti-poaching camps. But the flooded river transcends all boundaries and necessitates close collaboration of various arms of the State administration and civil society organisations.

In July 2019, floods inundated more than 70 per cent of the Kaziranga National Park. However, careful preparation and mitigation measures allowed several more animals to survive than in previous years. The death toll tallied to 223 (almost half from the 401 recorded in 2017). Photo courtesy: Arun Vignesh

The 2019 Experience

Nearly three months before the flooding, on April 22, P. Sivakumar, IFS, Director, Kaziranga National Park and Tiger Reserve, called for a flood-preparedness meeting. The meeting set in place a module of networking between the civil administration, park authority, NGOs, 33 Eco-Development Committees (EDCs), Village Defense Parties (VDPs) and various media outfits. A roadmap for effective pooling, mobilisation and allocation of resources channelled through all the stakeholders was created. A common goal – protecting the integrity of the park, safeguarding movement of the wild animals and addressing the needs of villagers around the park – connected all the teams.

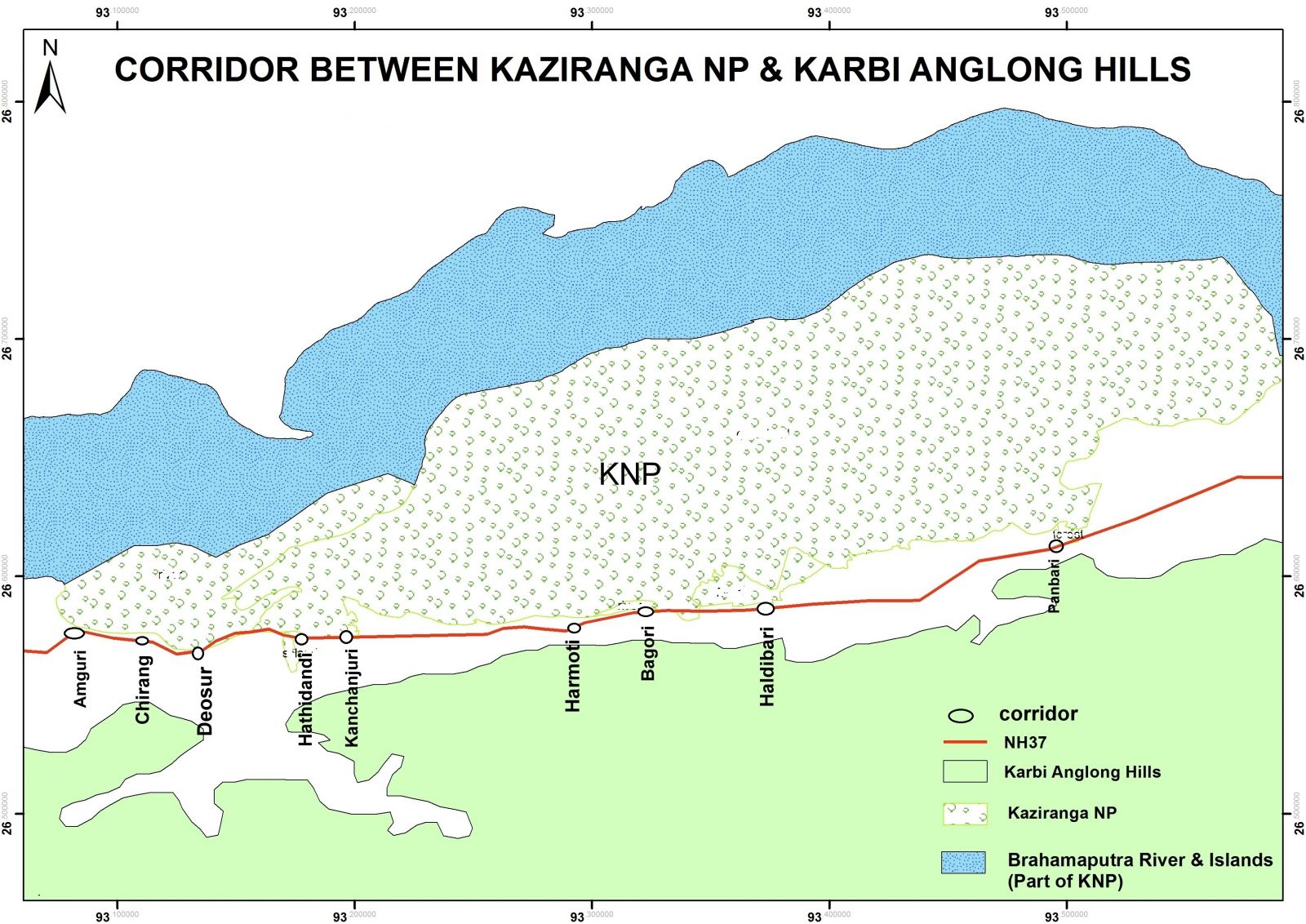

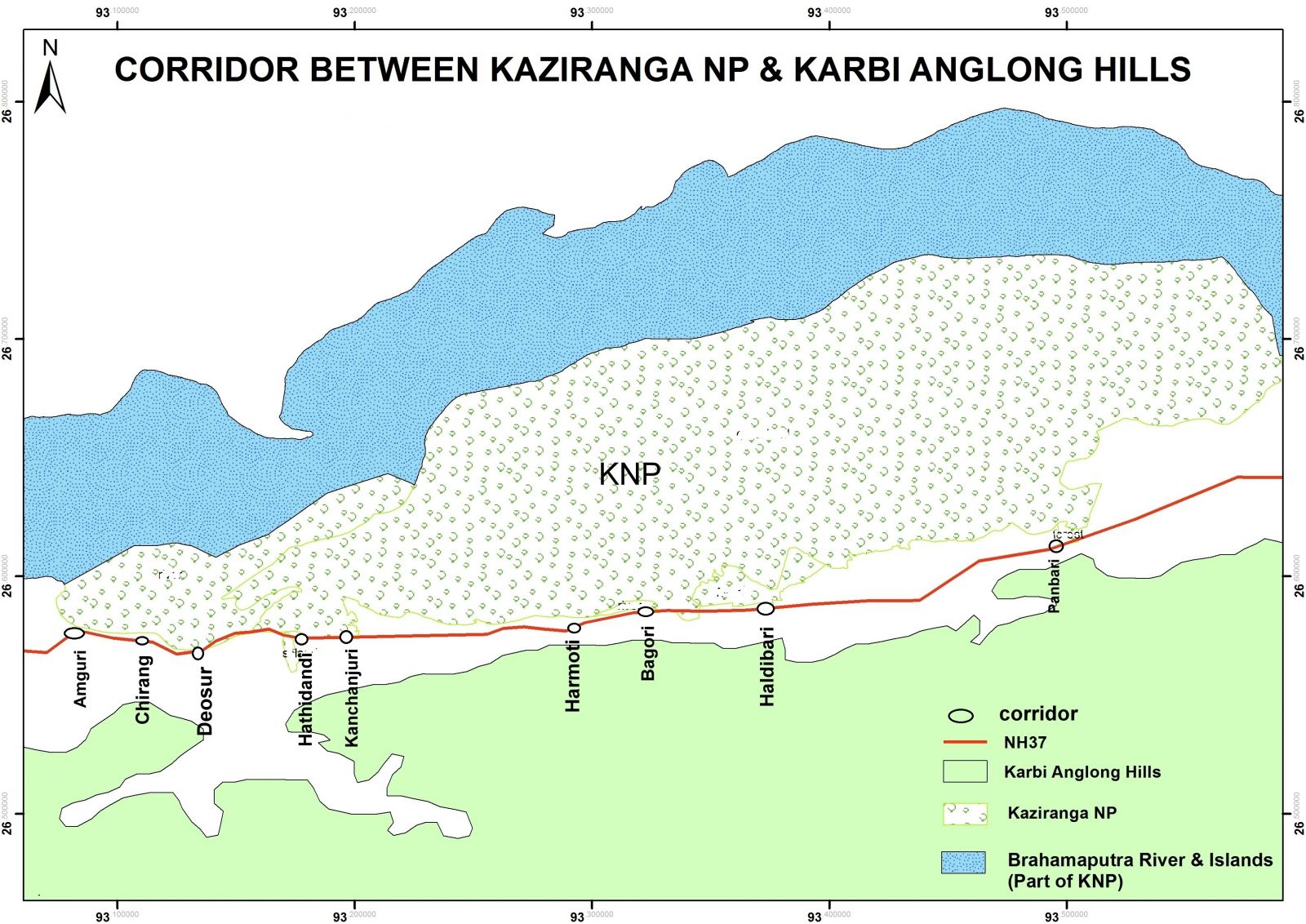

The Asian Highway 1 (erstwhile National Highway 37) is the lifeline for people in Northeast India. It also has ‘lines of life’, or wildlife corridors. The nine known wildlife corridors here are Panbari, Haldibari, Bagori, Harmoti, Kanchanjuri, Hatidandi, Deosur, Chirang and Amguri. Wildlife that attempts to escape the flooded waters in the park must cross Asian Highway 1 to seek refuge in the Karbi Anglong hills.

However, population growth and demographic changes have impacted the corridors. The mushrooming of hotels, resorts, restaurants, dhabas, shops, ancillary structures of the tea industry and other amenities with boundary walls have compromised the integrity of the corridors.

Every year as Kaziranga floods, animals must seek refuge on higher grounds in the Karbi Anglong hills. However, this journey is filled with perilous threats including having to cross a busy national highway (NH37). To prevent accidental roadkill, barricades are set up by the Forest Department to control vehicle movement. During the floods, Section 144 of CrPC was imposed to restrict vehicle speed to less than 40 kmph. Photo courtesy: Arun Vignesh

When the Waters Breach

On July 13, 2019, standing glued to our binoculars at the edge of the Gajraj viewpoint, we could appreciate the Brahmaputra spreading its wings and rushing in to engulf the park. The sandbank had disappeared. The grassland, where we had seen a rhino mother grazing with her calf by her side the previous day, was now an expanse of infinite water. The flood had arrived. It was not a surprise, as we were being updated twice a day by the Central Water Commission on the flow and water level of the Brahmaputra at key locations like Passighat, Dibrugarh, Nimatighat, Numaligarh, Dhansirimukh, and Tezpur. Dr. Satyendra Singh, IFS, former Director of Kaziranga National Park and Tiger Reserve, had said, “If the Brahmaputra flows at 106 m. at Dibrugarh for six hours, then you have less than 72 hours to fine-tune preparations before the flood hits Kaziranga.”

Section 144 of The Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 (CrPC) was imposed by the civil authorities on Asian Highway 1 to restrict the speed of vehicles, and the RTO/DTO was engaged for monitoring the speed restrictions (40 kmph.). Adequate barricades were placed along the highway between Panbari and Aamguri where wild animals were known to cross. An additional team of vets from Wildlife Trust of India-led Centre for Wildlife Rehabilitation and Conservation (CWRC) were also placed at the Western range, Bagori for clinical treatment of the injured wild animals.

By the next morning, the flood had inundated more than 70 per cent of the park. About 95 camps had witnessed the entry of water into the camp areas, and the roads inside the parks were inaccessible. There was a massive movement of wild animals crossing the highway and heading towards the only natural high ground in the south, the Karbi hills. Asian elephants, one-horned rhinos, Eastern swamp deer, hog deer, sambar, wild water buffalos, and snakes like king cobra, monocled cobra, Burmese python and many others attempted to cross the highway in search of natural highlands. Volunteers from the local community, through many NGOs, joined hands with the Forest Department and the district police day and night to ensure that road traffic accidents were minimised. The Corbett Foundation’s (TCF) wildlife rehabilitation project, which channelises the community’s concern for conservation, helped 63 wild animals during the flood. TCF’s 4WD vehicle – exclusively dedicated to the rescue and release of stranded wild animals – helped the timely transfer of wild animals either to safer locations when they were found fit or to the CWRC for better care and recovery. Adding to the stress, free-roaming dogs in the fringe villages were chasing and injuring hog deer. The floodwater was still rising.

The civil authority had to close down the highway the following morning. The floodwater was flowing a metre or so over the highway at five different stretches. A sense of disconnection prevailed upon us but fortunately, it didn’t last long. The floodwater started receding on July 16 and the highway was opened for vehicles. Intensified patrolling through the deployment of an additional 50 staff deployment and time card system continued as the wild animals kept moving across the highway. A passionately committed team of 1,374 individuals, dedicated for the protection of wildlife (ranging in ranks from forest guards to the Field Director) stayed away from their families and braced the challenges that the flood had forced upon them.

There are nine documented wildlife corridors connecting the Kaziranga National Park (KNP) with the Karbi Anglong hills. National Highway 37 slices these corridors, impeding safe passage of wildlife when floods strike. Map courtesy: Sumanta Kundu

Working Together for Safety

Three high grounds built in the villages adjacent to the western range of KNP In 2019, 95 of the 180 anti-poaching camps had become inundated due to flood waters. However, quick evacuation of staff ensured that there were no fatalities. for villagers and their livestock by The Corbett Foundation with support from the Hem Chand Mahindra Foundation proved helpful as a safe refuge for their livestock. There was also an exciting incident wherein a tiger entered a roadside shop; the alert and calm response of the park authority, according to the NTCA guidelines, ensured the tiger’s safe departure into the forest. The park also witnessed five of its sentinels sustain injuries while performing their duties. “Working for the park’s protection is supreme. I respect the buffalo, which injured me. My family is mentally prepared for such incidents, even when the park is not flooded. It is not only a question of making a living; we protect our heritage,” says Khageswar Gaur, a forest guard who was severely injured by a wild buffalo in the Western Range at Bagori. His colleagues Bhaskar Bora, Havildar Badan Phukan, Forijul Islam and Bastab Borkakoti, echoed similar sentiments despite encountering the rage of stressed wild animals during the flood.

While every death would hurt, the number of deaths of wild animals in 2019 during the flood eventually tallied to 223 (almost half of the 401 deaths recorded in 2017). The number of animals dying due to vehicular hits was 17. We wish it were nil, but it is a nearly impossible challenge. Floods are a natural way of weeding out poor, weak, old and sick animals, allowing the forest to restore itself with a healthy population. Some may argue then, why do we interfere at all? We do because there have been irreversible actions by humans in the last few centuries altering the landscape in such a way that fair competition in the wild is challenged today.

In 2019, 95 of the 180 anti-poaching camps had become inundated due to flood waters. However, quick evacuation of staff ensured that there were no fatalities. Photo courtesy: Arun Vignesh

Timely Interventions

In the last couple of years, 33 high grounds (the biggest one measures 200 m. x 50 m. x 5 m.) have been added to the existing elevated structures inside the park to provide safe refuge to wild animals during peak flood seasons, as a temporary shelter. One day, when the floodwater was at its peak, more than 80 animals were seen on two high grounds, which stood as giant rocks in the middle of the most massive temporary freshwater accumulation we had ever seen. Onehorned rhinos, a ‘not-so-social’ species, were found sharing the flat top surface of the mounds as well as the slant edges leading to the floodwater with over 80 other individuals of either their clan or a different species. The stress of an unfavourable season seemed to take away interspecies hostility.

The south-centric locations of these high grounds act as a temporary stopover for the animals to catch a breath before they restart their exhausting swim, as suggested by Dr. Satyendra Singh. We observed an evident use pattern, good intent, and an ecological micro-habitat building upon many such high grounds in the park. The greatest danger with such a temporary association lies in the threat of a disease outbreak due to stress or a decaying carcass. Building high grounds inside the park cannot be the quick-fix for challenges of corridor congestion along the southern boundary. “The only long-term and viable ecological approach would be to secure the Kaziranga-Karbi Anglong landscape as a unified entity”, says P. Sivakumar.

Village meetings held by partner NGOs and the Forest Department before the floods serve to prepare communities with adequate safety measures. They are also discouraged against interfering with or capturing distressed wild animals. Photo courtesy: Jadumoni Goswami

The Ecological Impact of Floods

Kaziranga did not get flooded during 2018. However, there was no study assessing the immediate impact of non-flooding on wetlands, exotic weeds, agriculture production and fishery around the park. We know that there is a positive relationship between historical catches of fish and water level in the Mekong river from studies there. It would be safe to assume that ecological, environmental and hydrological variables would moderate fish and agricultural production in the Kaziranga landscape too. It is vital to conduct scientific assessments and monitor how water level, duration and regularity of floods, the total area of floodplain and area of flooded vegetation affect food availability for the wild fauna and the agrarian community along the park. Rigorous research aimed at seeking ecological answers will unearth lessons for us for future food management. For now, the flood has recharged wetlands, and freed them of invasive Eichhornia crassipes. We lost part of the park to erosion – it has been established that around 90 sq. km. of the park landmass was lost during the course of the last century.

Various hydrological changes upstream in Brahmaputra’s national and international waters, coupled with climate change, are bound to bring a considerable difference in the flood patterns of the river in the future. Farmers like Krishna Saikia and iconic species like the one-horned rhinoceros and Bengal tiger will equally feel the wrath of the resulting habitat shifts. Can we, Homo sapiens get the pulse of these changes and make ecologically sound decisions for all living creatures that we share space with?

.JPG)

Villagers and their livestock find temporary refuge in one of the three high grounds built for them by The Corbett Foundation with support from the Hem Chand Mahindra Foundation. Photo courtesy: Naveen Pandey

A door-to-door vaccination drive based on a public-private partnership (PPP) is now annually organised in the area for active immunisation of livestock against diseases, considering the close interface they share with wild animals. Photo courtesy: Naveen Pandey

Saving People and Livestock

The Forest Department recognises that flood management also involves the protection of people and livestock near the park. There are hundreds of families living around the park rearing over 30,000 livestock. Inevitably, thus, an active interface exists where wild animals and livestock share space. With better knowledge and understanding of the risk patterns, disease outbreaks and impact of previous immunisation drives, a massive door-to-door vaccination is annually organised in the area for active immunisation of livestock against diseases such as Foot and Mouth Disease (FMD), Haemorrhagic septicaemia (HS) and Black quarter (BQ). Reaching out to every household with vaccines stored in ice-boxes is a timetested approach. In the first half of June 2019, a public-private partnership (PPP) model was put in place in the field of landscape epidemiology, implemented by the park authorities in collaboration with The Corbett Foundation, WWF India, Aaranyak, Wildlife Trust of India, Bhoomi and, State Animal Husbandry and Veterinary Department. Five teams led by nine veterinarians reached every household in 41 villages adjoining KNP and five small islands, locally called chapori, and immunised 8,822 livestock against FMD, HS and BQ.

The next step in ensuring flood-preparedness was village-level meetings with the community before the flood. Such meetings are attended by men, women and children of all ages and help in establishing communication channels for minimising potential losses and suffering. The discussions focus on how the community could safely respond to the challenges of the flood and how wild animals could be provided safe passage during the flood. Issues like capture myopathy in deer due to ignorant confinement and handling are discussed and discouraged. The park authority explains the legal consequences of confinement, capture and killing of any stranded wildlife. NGOs, often, are better connected with the community and effectively lead such meetings. In June 2019, 42 village meetings were organised in villages and schools of Kaziranga jointly by partner NGOs and the park authority. Torchlights were distributed to the members of Village Defense Parties (VDP) for effective patrolling of the area during and immediately after the flood.

A documentary film ‘Sahjeevan’, made by Pelevizo Meyase and Lalboy Misao from Tezpur based Green Hub, was widely screened during these meetings. The film, shot during the flood of 2017, showcased various mitigation measures by The Corbett Foundation and park authorities to face annual flooding.

Floods are vital to Kaziranga’s ecosystem health. But mismanagement of land outside has disturbed the ancient equilibrium that enabled wild species to hold their own. Here are 15 ways to protect Kaziranga from flood impacts caused by outside mismanagement.

1. Conduct awareness meetings before the flood

2. Promulgation of Section 144 of CrPC

3. Establish a flood monitoring cell

4. Network with volunteers

5. Create mobile patrolling squads

6. Evacuate staff from flooded camps

7. Set up temporary camps at vulnerable sites

8. Deploy additional forest staff

9. Engage District Transport Officers

10. Deploy an additional police force

11. Issue time cards for vehicular speed control

12. Use country boats alongside powerboats

13. Round-the-clock rescue and rehabilitation

14. Intensification of patrolling

15. Communicate daily updates to all stakeholders

Naveen Pandey is the Deputy Director and Veterinary Advisor, The Corbett Foundation, Kaziranga, and Rohini Ballave Saikia is an IFS and former Divisional Forest Officer, Eastern Assam Wildlife Division, Kaziranga National Park.