Pakke's 'Irregulars'

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 41

No. 8,

August 2021

Unheralded heroes on the frontlines of conservation

By Pranav Capila

In June 2021, ‘casual’ or ‘temporary’ frontline staff working in the Pakke Tiger Reserve, Arunachal Pradesh, went on a day-long strike to protest the non-payment of their wages since December 2020. This included members of the Special Tiger Protection Force (STPF), who constitute the backbone of wildlife protection in Pakke. Pranav Capila had visited the tiger reserve in January 2020, staying with and walking on patrol with STPF personnel. This is a story about those invisible, unsung frontline heroes.

PART I: BOOTLESS IN KHARI

Three damp field boots huddle in a patch of sunlight next to the frontline staff quarters at Khari Camp, Pakke Tiger Reserve. They shiver in the stiff morning breeze, eyelets laced with fear, tongues hanging out from the previous day’s exertions. The fourth of their company is missing, having perhaps legged it under cover of night.

Tinku Kino emerges from the room nearest to them – the room with the monobloc and the cane chair on the porch, the clothes flopped onto the washline, the sky blue door with ‘Dil Mange More’ (The Heart Asks More) and ‘tinku’ calligraphed on the outside. He wears a cap, a brown jacket over his camo uniform, and bright orange flip-flops. A dao (a short sword that takes various forms across the tribal Northeast) is slung around his shoulders. A waterproof pouch hangs from his neck.

A sigh of relief rises like a mist around the boots as Tinku walks past them without a glance. His patrol today will take him along the riverbed, the wet conditions making boots a liability. Field boots are lucky if they last three months in these parts. At least they’ve been spared this morning’s grind.

Velcro sandals would have suited Tinku’s purpose more than flip-flops but his last pair broke some weeks ago. Since he buys them out of pocket, he is making do. He walks downhill to the Khari river and turns upstream towards a minor tributary, the Lalling nullah. He stops a moment here, retrieves his cellphone from the waterproof pouch and launches the M-STrIPES app – ‘Monitoring System for Tigers: Intensive Protection and Ecological Status’, deployed across tiger reserves by the National Tiger Conservation Authority (NTCA) in 2010. He takes a selfie and enters his name into the app. His position appears on an offline map of the tiger reserve; the route and distance of his morning patrol will now be part of the official record.

_1628505827.jpg)

Tinku Kino has been an STPF guard since 2013, with a salary of Rs.14,000 a month. As the STPF has not been regularised in Arunachal Pradesh, such foot soldiers are deemed ‘temporary’ or ‘casual’ workers. They often fall into debt traps as they are forced to borrow money to sustain their families, since their wage disbursements are routinely delayed by the state government. Photo: Pranav Capila.

It is 6.30 a.m. and the dawn sun feathers a rosy blush across all of Pakke. The nullah sings and gurgles, meandering its manyfingered way through the tangle of subtropical jungle. Tinku maintains a brisk pace along a jeep track, stopping occasionally to photograph animal signs and sightings. Jungle cat scat, leopard pugmarks (still wet), bear pawprints, elephant footprints, the spot where a wild pig poked his tusks out of a thicket and beat a panicked retreat a minute ago, fresh elephant dung, more elephant footprints – everything is logged in the app.

Tinku wades across a knee-deep rivulet and reaches under a bush, retrieving a dull brown rectangular box: a camera trap. He adjusts the preset capture interval, replaces the batteries and conceals the camera once again. With the nullah sickle-curving around a bend, he decides to take a trail that cuts through the jungle. On the other side, just as he emerges from the undergrowth, he stops dead. His right arm shoots out to the side, rigid, like the boom barrier at Pakke’s West Bank entrance. With that outflung arm he probably saves my life.

A Tuskless Dilemma

Tinku is a member of the Arunachal Pradesh Special Tiger Protection Force (STPF). He has been with the STPF since August 2013, posted first at Upper Dekorai and subsequently at Khari. His association with Pakke, however, began several years prior. When he was a lad just out of school, he began working at the Nameri West Camp as a beat guard, a ‘daily wage’ or ‘casual’ worker, earning Rs. 1,430 a month. “Uss time main bhaag gaya thha...” he says; “I ran away... I was terrified of living in the jungle.”

On April 19, 2007, Forest Guard P.D. Majhi was shot and killed in an encounter with poachers in Pakke. Young Tinku was among the frontline staff called to the scene. “I will never forget what I saw that day,” he says. “There was blood everywhere. Majhi sir’s body was all stiff, hunched over. One of the poachers had been captured. Jaimala [a matronly camp elephant] was called for and they took Majhi sir to the Range Office on her back. Four men marched the poacher back on foot.”

It was all too much for the boy. He left soon after, began a Bachelor’s degree in Political Science in 2010, got married in 2011. That he found himself back with the Forest Department in 2013 was, he feels, inevitable. “I needed a job and you don’t get many other opportunities out here.”

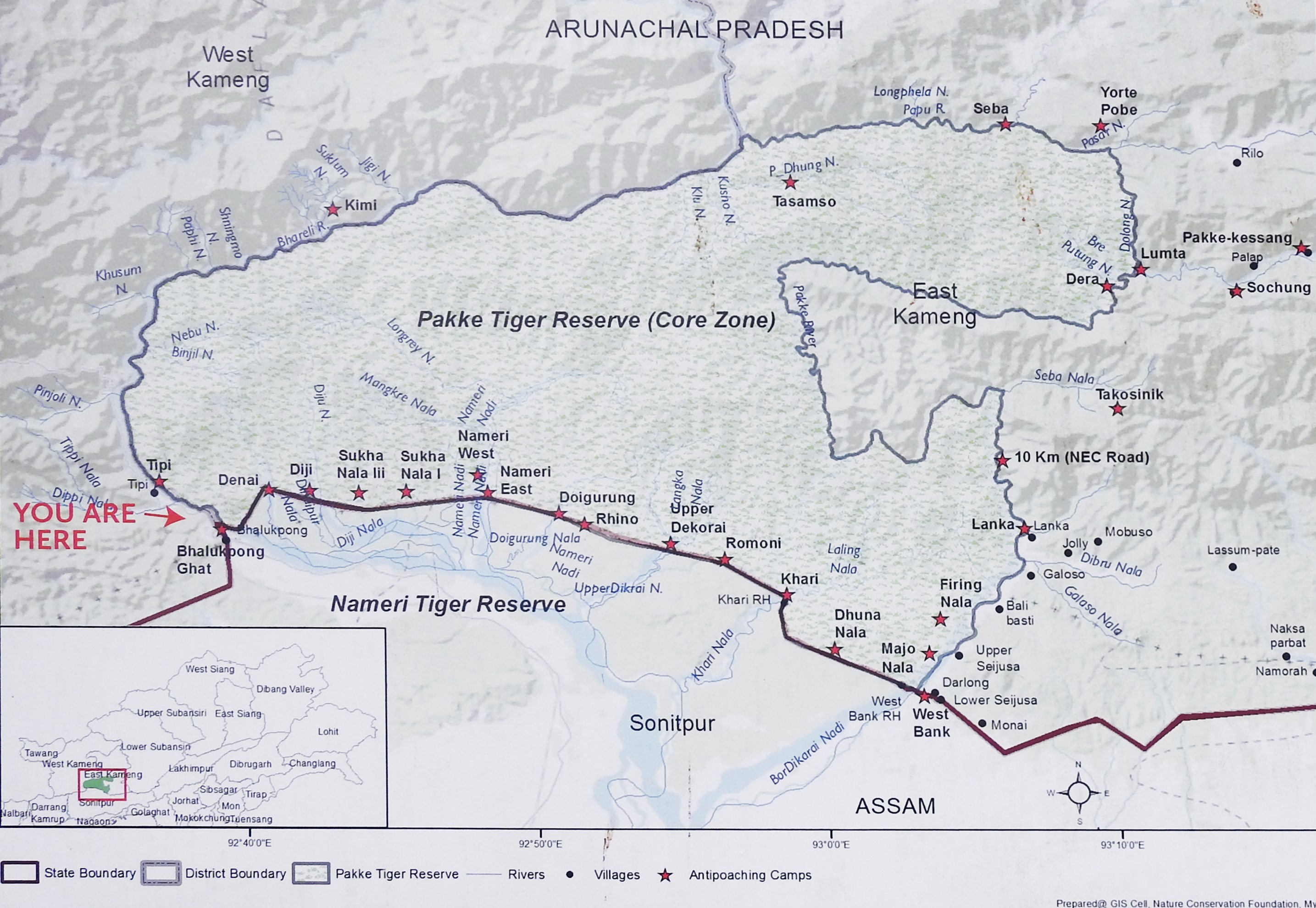

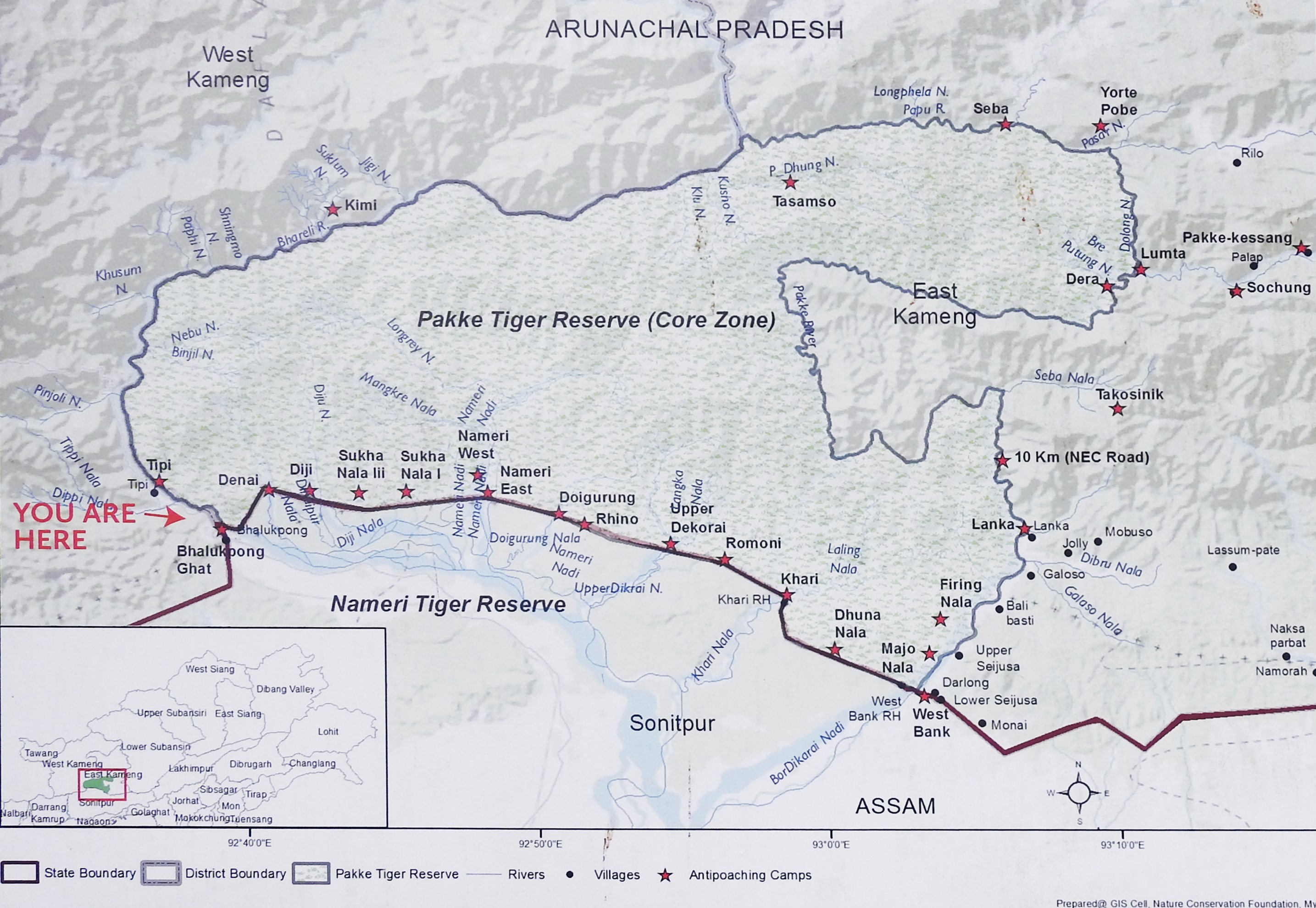

Map of the Pakke Tiger Reserve and neighbouring areas. Courtesy: Arunachal Pradesh Forest Department.

He has been in the STPF for over six years now but remains a casual worker. He earns just Rs. 14,000 a month, plus (inadequate) rice rations. His wages, often delayed by several months, are effectively paid by the kilometre, since STPF personnel must walk a minimum of 200 M-STrIPES-logged km. on patrol per month.

We walk 8.5 km. together on that late January morning. He tells me about his wife and five-year-old son and how fortunate he feels that they live just a kilometre from the West Bank gate. Some of the STPF guards, he says, have families far away and get to go home just twice or thrice a year. He asserts that he is no longer the frightened boy in the jungle, describing several encounters with Pakke’s famously aggressive makhnas (tuskless male elephants) and the time he saw a leopard at close quarters (“just a glimpse and it was gone”). He has learned that comradeship is at the heart of life in the jungle: “It’s not as if we never feel tired when we are out on patrol, or afraid when we encounter an animal or a poacher. But we keep each other’s spirits up. We look out for each other; we have each other’s back.”

As if to underscore that point, he stops me in my tracks as we emerge from that shortcut through the trees, just before we reach the water where, less than 10 m. away, a makhna stands midstream: massive, grey and glad to see us.

Although that last bit is probably not true – the erect elephantine member swinging between the makhna’s hindquarters has more to do with the pre-musth state he is in. A good reason to keep absolutely still.

“We’ve made him uneasy, he may charge,” Tinku whispers. But the makhna surveys us for a minute or 10, then lumbers into the tall grass and melts into the trees beyond. Giving him a wide berth, we carry on up the jungle.

%202.jpg(1)_1628508578.jpg)

The makhna the author encountered on patrol. Photo: Pranav Capila.

PART II: ALONG THE BACKBONE

Pakke is one of the last magical places on Earth. When I first came here five years ago, I was enchanted by its ancient, near-impenetrable rainforest. I listened to the night songs of elephants, and heard Great Hornbills barking at dawn, and spent my days witnessing the rewilding of a rescued bear cub. I also encountered Schrodinger’s elephant – a makhna who both did and didn’t chase me for a breathless kilometre down a jungle path (I never looked back to check).

No irate elephant ushers me through the jungle near the West Bank Range Office this morning. My only companion is Sanjay Tisso, who has worked in Pakke since 2007, first with the anti-poaching squad and subsequently with the STPF. (Sanjay is also something of an artist; his murals adorn the tourist centre at West Bank.) Waiting to accompany a VIP safari arriving from the Pakke Paga Hornbill Festival in nearby Seijosa, he is in full uniform, scrubbed and shining from cap to boots, and armed with a .315 rifle.

The Forest Department provides each STPF guard with a raincoat, a pair of jungle boots and enough cloth to get a shirt and a pair of trousers stitched. The uniform and boots, to be worn in field conditions day after day, are required to last a year. (Field staff hadn’t received replacements in two years when I visited). “Earlier we also used to get a torch, an umbrella and a mosquito net if there was a tiger or elephant census,” Sanjay says. “But not in recent years.” The headlamp he wears on night patrol, the dark green jacket with which he keeps out the winter chill – he bought them himself, from a local market.

Even firearms, it seems, aren’t always deemed essential: there has been a crippling shortage of weapons for Pakke’s frontline staff for several years now. And for once funds aren’t the issue; the state government hasn’t got around to clearing the purchase of weapons, despite repeated entreaties.

Like the other STPF guards Sanjay received six months of overdue wages just a day ago. STPF personnel get their wages through Project Tiger, a Centrally Sponsored Scheme. The issue seems to be that the state government, which has to contribute just 10 percent of the funds, holds up the entire disbursement until it can release its share. “It’s an impossible situation to be in,” Sanjay says. “Only we know how we run our households without a salary. Our children’s education suffers. We can’t even buy them a toy during the festive season.”

_1628506678.jpg)

Sanjay Tisso has worked in Pakke since 2007, initially with the antipoaching squad and subsequently with the STPF. An artist in his free time, he is seen here in full uniform armed with a .315 rifle at the Khari Camp. Pakke’s frontline staff have been faced with a shortage of firearms for several years, because the state government has not issued the requisite permissions for their purchase. Photo: Pranav Capila.

The Empty House

From West Bank to Khari to Upper Dekorai I go, past Tarzen and Rhino Camps and beyond Nameri West where an artificial salt lick attracts wild buffalo, sambar and elephants every afternoon. Through the singing Nameri river to the Nameri East Camp, located in a clearing at the tri-junction of jungle roads.

With its occupants out on patrol, Nameri East seems desolate; a study in concrete grey and rusted tin, solitary in its solar-fenced cocoon. There is a rudimentary kitchen amidst the 16 pillars on which the camp is perched. Four wooden benches, low enough to squat on, gather around a stonehenge stove top. It is here that the men will sit when they return in the early evening, here that they will cook and eat, and share their stories and songs.

The living quarters are up the stairs, beyond a heavy trapdoor. There is a storeroom for grain and other supplies, a tiny toilet, and two rooms with rough-hewn beds sidled into the corners. There are quilts and sleeping bags here, and clothes hanging off nails on the unpainted walls. There are toothbrushes and razor blades, a porcupine quill, a needle and thread, a bottle of Nivea face wash.

A ginger moggie pokes a paw out from under one of the doors, thinking its humans are home. Nothing else stirs.

(1)_1628508689.jpg)

The Nameri East anti-poaching camp. Photo: Pranav Capila.

PART III: TIPI TIPI TAPPED

Range Forest Officer Kime Rambia is worried about his ‘boys.’ This is not unusual, since Rambia is the kind of officer who is always worried about his boys, as he calls the field staff working in his Range. It is, indeed, the measure of the man – every conversation veers towards his boys and the hardships that they face in the field.

As we drive out from Nameri East past Sukha Nala I and II, Diji Camp and Denai Camp, Rambia tells me how delayed wages force the men into a cycle of debt and repayment. He tells me of the men who, disheartened and desperate, left Pakke never to return.

We reach Bhalukpong Ghat and cross the Tipi River by country boat, and he tells me of the men who died on duty – six in the six years that he has been in Pakke. Just yesterday, Ramesh Orang, a beat guard training to be an elephant helper, was killed by a captive elephant at Doigurung Camp in the Seijosa Range.

Rambia drops me off at the Tipi River Camp. When we speak again six months later, I ask him how he fared during the nationwide lockdown. “The lockdown was announced without warning and we had problems arranging rations for staff in the anti-poaching camps initially. We also had to step up night patrolling and there were a couple of encounters with poachers. The boys have had a tough time of it. Some of them haven’t seen their families in months,” he says worriedly. It is, indeed, the measure of the man.

STPF frontline workers are seen rafting across the Kameng river near the Tipi range on a route fraught with danger. Pakke is flanked by the Kameng river to the west and north, and the Pakke river to the east. Photo: Paro Natung.

By the Jade River

The Tipi River Camp stands on a rise next to the river. It is an austere structure, just three bare rooms and a toilet raised up on stilts. Field staff don’t reside here – this is a transit camp used to patrol some of the more inaccessible parts of the Tipi Range – so it lacks the lived-in feel (and furniture) of other camps.

Last night, the four STPF guards I’m with – Nabam Rakesh, Tangru Sangchoju, Lokhiram Ronghang and Chandan Patro – slept on the concrete floor in their sleeping bags. Now, at 6 a.m., they are reheating our dinner (potato curry, rice and a local saag-patta I can’t remember the name of) so we can have a bite before the day’s patrol.

Rakesh, who is 23 years old, has been with the STPF for six years. He shows me a camera-trap image he has on his phone: the leopard that nearly killed him three years ago. “He came up behind me when I went down to the river to collect water”, he recalls. “He had me in his jaws. I remember the blood and the pain. I don’t know how I got away.”

Never one to play second fiddle, Tangru (49 years old and a former hunter) also has a photo to show me. Not of the wild elephant that once trampled him, but of a high-rise in Delhi, which he recently visited for the premiere of an Animal Planet documentary he had a starring role in.

The men are in good spirits, having received their overdue wages. There is a palpable sense of relief, even though they know it will be short-lived. “We live on borrowings; we have debts to pay off with interest. The money will soon be gone,” Lokhiram says. But they shrug off their troubles and fears as they have a thousand times before and get to work. A rubber raft is unpacked, inflated and carried down to the river. We row across the jade water to a beach on the other side. The team’s details are entered into the M-STrIPES app and the day’s patrol begins.

This is the toughest jungle terrain I have ever walked: tripping, snarling creepers, squelching 60-degree ascents, and the kind of undergrowth your legs vanish into only to be found a kilometre later. We stop to examine camera traps at three pukris (ponds); the images show elephants a-chillin’, sambar deer a-wallowing and a family of civets feasting on frog eggs. I learn from Rakesh that placing dried elephant dung on a camera trap will keep animals from messing with it. I learn from Lokhiram that a leaf skilfully folded can become a cup to drink from a stream. I learn from Chandan that the creeper he calls ‘pani lota’ can be a source of fresh water in a pinch. And Tangru, like a proud parent showing off his rainforest’s repertoire, brings me an assemblage of plant items: junglee adrak Cheilocostus speciosus, the sweet and earthy bark of gonsorai Cinnamomum cecidodaphne and the stretchy resin from a giant ‘labber’ (rubber) tree Ficus sp.

_1628507928.jpg)

(Left) Tangru draws rubbery resin from a giant labber (rubber) tree. (Right) Chandan drinks freshwater stored in pani lota, a creeper. Photos: Pranav Capila.

We return to the camp in the afternoon along a treacherous rocky path I have labelled ‘Bouldersmort’ in my notes. An eight-kilometre patrol according to M-STrIPES, but I am totally leached, and leeched. At twilight, just as the hornbills start settling into the trees opposite the camp, I leave Pakke.

I leave, and gradually I forget. On my desk the labber loses its elasticity, the gonsorai bark loses its scent. I forget about Tinku and Sanjay, Tangru and Rakesh, Lokhiram and Chandan.

But forgotten or not, they walk. From daybreak till twilight, day after day, they walk out on patrol. And under the moonlight, they walk out on patrol. And through the pandemic and its lockdowns. Across riverbeds where pugmarks glisten in the soft blush of dawn. Through jungles so dense that every step is a negotiation. They walk, and returning to their camps, they cook and eat a modest meal, and sleep a weary sleep on creaking beds, or huddled together on a concrete floor.

The next day they walk again. Sometimes never to return, for death is a companion that accompanies them on patrol every day. They die by tooth and claw, in encounters with elephants, and by the poacher’s bullet. They die, too, by the slow strangle of our indifference. Under-equipped and poorly paid, sometimes unpaid for months on end.

And yet, they walk.

Ignored, unappreciated, invisible, they patrol this slice of paradise.

Regularising the STPF

%20Chandan%20Patro,%20Tangru%20Sangchoju,%20Lokhiram%20Ronkgkhang%20and%20Nabam%20Rakesh%20at%20Tipi%20River%20Camp%20(Photo%20-%20Pranav%20Capila)_1628507619.jpg) (From Left) Chandan Patro, Tangru Sangchoju, Lokhiram Ronkgkhang and Nabam Rakesh at Tipi River Camp. Photo: Pranav Capila.

(From Left) Chandan Patro, Tangru Sangchoju, Lokhiram Ronkgkhang and Nabam Rakesh at Tipi River Camp. Photo: Pranav Capila.

Despite the MoU signed between the National Tiger Conservation Authority (NTCA) and the State of Arunachal Pradesh (among other states) for ‘Raising, arming and deploying the Special Tiger Protection Force (STPF)’ in 2009, and although the

Arunachal Pradesh Forest and Special Tiger Protection Force Act was passed in 2012 (coming into effect vide Gazette Notification on 14/03/2013), the STPF has yet to be regularised in the state.

Thus, STPF personnel in Arunachal are still ‘temporary’ or ‘casual’ workers. They earn meagre amounts and are not issued the ration allowances that permanent staff like forest guards receive. They are also subject to the vagaries of wage disbursement that plague casual workers across the country. When I visited Pakke in January 2020, STPF personnel had not received wages in several months because the state government had not released the requisite funds. (A lump sum amount covering six months’ pay was credited to their accounts between January 18 and 20.) Sadly, this pattern continues and staff had not received wages for six months when they went on strike in June 2021.

Earlier, a series of representations were made to the Government of Arunachal Pradesh by the Pakke Tiger Reserve Casual Workers Welfare Association (in April 2017) and the Pakke Tiger Reserve Workers Union (in March 2019), to (a) initiate the STPF recruitment process and (b) secure 30 per cent reservation in the new, regularised force for casual workers already working in the STPF. As these were fruitless, a Writ Petition (WP 146 AP 2019) was filed before the Itanagar Bench of the Gauhati High Court in May 2019, seeking the same.

“Despite the central government having sanctioned these posts, the state government has not regularised them for a decade,” said advocate Nabum Rama, representing the STPF ‘irregulars’, when I spoke to him in March 2020. “The buck (for initiating recruitments) is being passed from the Forest Department to the police and vice versa. But we can expect a favourable verdict soon. Final arguments will be presented before the High Court by the end of the month.”

But by the end of March, the COVID-19 pandemic held sway. Hearings were scheduled in January and February 2021, but postponed. Final arguments have still not been heard and as of July 2021, the matter of ‘Shri Radhe Nabam & 42 Ors. versus State of AP & Ors.’ remains in limbo.

Pranav Capila is an editor and writer who tells stories about wildlife, wild spaces, and unsung heroes on the frontlines of conservation.

_1628505827.jpg)

%202.jpg(1)_1628508578.jpg)

_1628506678.jpg)

(1)_1628508689.jpg)

_1628507928.jpg)

%20Chandan%20Patro,%20Tangru%20Sangchoju,%20Lokhiram%20Ronkgkhang%20and%20Nabam%20Rakesh%20at%20Tipi%20River%20Camp%20(Photo%20-%20Pranav%20Capila)_1628507619.jpg)