Seeing red

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 35

No. 2,

February 2015

By V. Deepak

On January 12, 2007, Silamban, my field guide, and I were walking through a riparian patch in the Anamalai hills of Tamil Nadu. To our pleasant surprise, we encountered a massive mugger crocodile Crocodylus palustris basking on a sand bank of a rivulet. As we stopped to watch the mugger, a snake suddenly fell to the forest floor from a nearby tree. Rushing forward for a closer look, I identified the dead serpent as a coral snake. Although coral snakes are venomous, they are known to be hunted by raptors, and by a stroke of luck we happened to be at the point of delivery when an unidentified bird of prey had dropped its quarry. My knowledge of snake identification was a bit rudimentary at the time and I couldn’t identify the creature further. Consequently, I reached out to my friend and fellow herper, Harikrishnan, and after scrutinising photographs closely, we realised that the specimen represented one of the rarest coral snakes found in the Western Ghats, the Bibron’s coral snake Calliophis bibroni!

Coral hues

Although I was studying tortoises, observing and photographing rare and endemic snakes was a hobby. A year later, another companion and guide, 60-year-old Karuppasamy, picked up a tiny snake crossing the road and brought it to my base camp. It was a live coral snake hatchling with bright red hues on both its dorsum and its belly – another Bibron’s coral snake. In August 2008, I met Dr. Eric Smith, an authority on coral snakes who has travelled to museums across the world to study them. The samples he had thus far examined were historical specimens collected by G. Jan, Col. R. H. Beddome and Col. Frank Wall, renowned herpetologists of the 19th and 20th century.

Eric informed me that most of the smaller specimens he checked at the museums had less of the dark shades and more of the faded remnants of bright colours. It turns out they have remarkable colour variation during their development from hatchlings to adults, a trait that is probably unique to coral snakes. Most coral snakes have bright colours, which are thought to function as a warning (aposematic), while colour patterns matching the environment are thought to aid camouflage. Sometimes the patterns take the form of stripes or bars, with disruptive shades being particularly useful when the reptiles must make good an escape.

Coral snakes in India come in all shades. The Beddome’s coral snake, slender coral snake and striped coral snake (C. beddomei, C. melanurus and C. nigrescens respectively) have cryptic dorsal colours, with a disruptive pattern of lines and/or blotches, though some are unicoloured. Castoe’s coral snakes C. castoe, on the other hand, have a uniform colour on the dorsum, while Beddome’s coral snakes have two rows of dark spots with irregular margins on both sides of a vertebral line. The undersides of the slender coral snake, Castoe’s coral snake, striped coral snake and Beddome’s coral snake all possess bright colours.

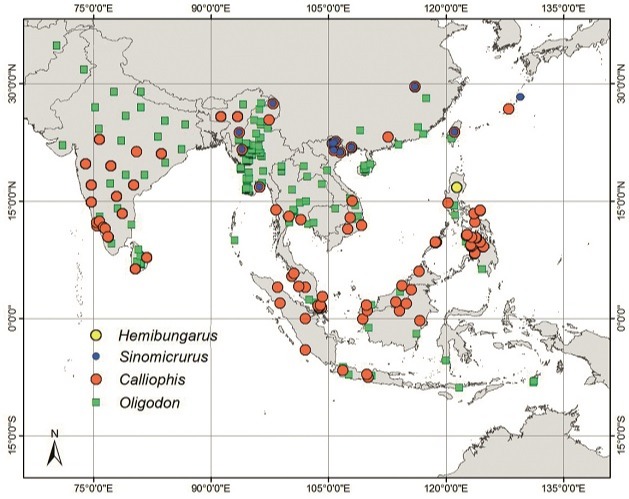

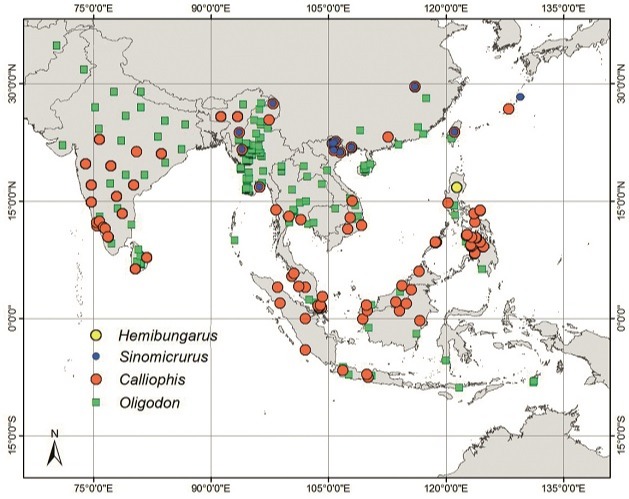

Range map depicting the old world distribution of different genus of coral snakes. (Most references included from the Global Biodiversity Information Facility portal)

A new coral snake species

In January 2009, I was back in the Anamalai hills to radio-track endemic turtles (the cane turtle and Travancore tortoise). On a misty morning, Silamban and I flushed a herd of gaur through the forest understory. Stepping back, we waited until there was no noise, before moving onward. A usual jump across a huge fallen log to my sampling site turned unusual, because this time there was a snake in my landing spot. Again, a dead adult Bibron’s coral snake, with puncture marks on the head. Finding the same rare species of snake in three consecutive years seemed almost too lucky to be true!

Dr. Varad Giri, one of India’s most respected herpetologists, says: “If you understand the known species, it is just a matter of time before you identify and describe new species.” Eric has just such a good understanding of the coral snakes of the world, and it was only therefore a matter of time before he honed in on a new species. Sure enough, he identified and described a new species from the broken pieces of a coral snake found in the 19th century collection at the Bombay Natural History Society Museum. We chose to name it Calliophis castoe after another renowned coral snake expert, Dr. Todd A. Castoe. Castus, a Latin word which also means pure, refers to the characteristic unmarked dorsum of the snake. This species occurs in Goa, Karnataka and Maharashtra, along the Malabar coast and adjacent Western Ghats.

The genus Sinomicrurus has six different species distributed through the Indo-Burmese region all the way to Japan. Currently, we have been able to identify one species in northeastern India, but very little is known about it. It sports a brightly-coloured dorsum (firebrick red) with black bands and a head with distinct cream-coloured marking. I am yet to see one, but some herpetologist friends have been generous enough to share their photographs.

An adult striped coral snake’s tail in a startling, characteristic defensive display (inset). Coral snakes have anatomically evolved to sport vivid colours and patterns that work well as an anti-predator feature. Photo Courtesy: Saunak Pal, Inset: Rohit Naniwadekar/ KNP

The Castoe’s coral snake was described recently in 2012 from western peninsular India. It is easily distinguishable from other Indian coral snakes by its unpatterned and unicoloured dorsal scales. Photo Courtesy: Hemant Ogale

Tail display, behaviour

and mimicry

Dr. Harry Greene, an ophiologist, did an extensive review on defensive tail displays of snakes and amphisbaenians (worm lizards or legless squamates). Coral snakes are known to display their tails so that they become unusually conspicuous. It is hypothesised that this could be a response to stress, such as a sudden tactile stimulus, and is probably an antipredator strategy. Rohit Naniwadekar and I once documented this behaviour in a striped coral snake while photographing it in Kudremukh, Karnataka. I have not seen any Calliophis melanurus exhibiting this tail display, but reptile enthusiasts from many parts of peninsular India have shared their observations. One such observation by Akshay Khandekar from Sangli is exceptionally notable. Akshay says that sometimes the snakes coil their tail, but at other times they just turn the tail to display the bright colours on the underside.

Tail coiling behaviour is observed in many snakes around the world, including some that mimic venomous snakes. Oligodon cyclurus, a kukri snake from northeastern India is an example of a non-venomous snake mimicking the venomous Sinomicrurus macclellandi (which exhibits similar displays). Oligodon dorsalis, another kukri snake from northeastern India coils its tail to display it and is so brightly coloured that it could be easily confused with a venomous coral snake. By contrast Oligodon albocinctus (Arindam Kishore’s observations), another species from northeastern India, lacks the brightly coloured tail but nevertheless does coil its tail for display.

Sherman Minton, a renowned herpetologist who undertook extensive studies on reptiles in Pakistan, notes that Oligodon taeniolatus, a widely distributed species of the Indian subcontinent, also curls its tail. A quick Google search reveals images of O. taeniatus from Bangkok,

O. octolineatus from Singapore and O. ornatus from Taiwan. All are kukri snakes that coil their tail and display bright colours. Coral snakes are, predictably, also found in this part of the world.

Photo Courtesy: Sandeep Das

Photo Courtesy: Abhijit Das

The non-venomous geographical co-habitant of the old world coral snakes – kukri snakes – have fascinatingly evolved similar behavioural as well as anatomical traits of the venomous coral snakes. The lesser-known, short-tailed kukri, is an interesting coral snake mimic. It sports stripes like that of a striped coral snake and its dorsal region is similar to the Bibron’s coral snake. A short-tailed kukri (Above) takes on its distinctive defensive stance with its head raised and body coiled sideways. Oligodon dorsalis, a kukri snake (below), though not as brightly adorned, mimics the tail coiling trait of the coral snakes.

DESIGNS FOR LIFE

As with several other species, the coral snakes’ colours are directly connected to their alternating roles as predator and prey. Many organisms use aposematic signals to warn predators of their unprofitability. Such signals include conspicuous colours, odour and sound. These characteristics have been observed as benefitting both predator and prey. Aposematic colours are so useful that some harmless organisms have even evolved to mimic aposematic species. Such patterns are known as Batesian mimicry named after the English naturalist Henry Walter Bates, who accompanied Alfred Russell Wallace on his famous voyage to the Amazon. Bates’ discovered that some of the butterflies of one family he had collected always had a number of practically indiscernible butterflies that belonged to another family. Bates’ findings on the Amazonian butterflies led him to hypothesise that many of the non-harmless species mimicked the poisonous ones. Around the same time a German naturalist named Fritz Müller proposed a concept; in which two or more poisonous species that may or may not be closely related and share one or more common predators, mimic each other’s warning signals. This pattern came to be known as Müllerian mimicry.

Bright colours and mimicry

Greene notes in his observations that “a kukri snake Oligodon cyclurus from Tam Do, Vietnam, possessed the same colourful pattern as that of Sinomicrurus macclellandi, the kukri also thrashed erratically and bit readily like S. macclellandi.” Oligodon cf. melanozonatus, a kukri snake from northeastern India has bright colours and bands similar to those of a MacClelland’s coral snake.

Mimicry of venomous snakes by non-venomous ones is one of the well-studied subjects in the new world tropics. However, in the old world only a little is known about this, that too from anecdotal records. Here, I’d like to share some of my own observations from the Western Ghats.

In the southern Western Ghats (Agasthyamalai), lives a lesser known snake called the short-tailed kukri Oligodon brevicauda. I went there with a team to monitor lion-tailed macaques. After the survey I moved around exploring the rainforest patch with one of my more reliable field guides, Rajamani. Within a few minutes Rajamani ran a few steps back and exclaimed pambu (snake)! For a second I missed the snake, the lines on their body can function as an optical illusion and they are fast moving, but I managed to catch it and took it back to the base camp to count scales and identify the species. It was a short-tailed kukri with stripes similar to those of a striped coral snake. The belly was very similar in colour to that of a Bibron’s coral snake! Few years after my observation, two herp enthusiasts from southern India recorded O. brevicauda from the same hill range. Seshadri and Sandeep Das also recorded an interesting display; the snakes coiled their body sideways and raised their head like a trinket snake. I suspect that this is also an attempt to display the aposematic colours on their ventrals when they perceive a threat.

Why kukri snakes?

Kukri snakes or snakes of the genus Oligodon co-occur with coral snakes in many parts of the old world. They have evidently evolved behavioural traits such as tail coiling, similar to those of a coral snake. Apart from behavioural traits, some kukri and coral snakes have remarkably similar colours. Their co-occurrence is not just geographic, they actually live in similar microhabitats! Like coral snakes, kukris are generally terrestrial. To my knowledge kukri snakes, which look similar to coral snakes, occur in many places from the Western Ghats to Taiwan. Therefore, it is compelling to call them mimics of their venomous kin.

Other snakes resembling coral snakes

Many amateur snake enthusiasts from peninsular India have mentioned that the Duméril’s black-headed snake Sibynophis subpunctatus is also a mimic of the slender coral snake. The black head marking and the dorsal colour are uncannily similar to the slender coral snake, though they do not exhibit any particular display. Their distribution almost exactly overlaps that of the slender coral snake in India and Sri Lanka. Apart from the black-headed snakes, several bright-coloured snakes resemble coral snakes in the old world, but I would need to undertake exhaustive literature research before I can write about them.

When I saw my first coral snake, I was surprised to learn that such colourful snakes exist in India. And the more I learned about them, the more fascinated I became. The fast-vanishing rainforests of India are home to an incredible diversity of magnificent creatures. I am trying to understand the life of just this one intriguing group of reptiles and hopefully the knowledge I disseminate about these snakes that I have come to love, will end up protecting them and their habitat.

As the Senegalese conservationist Baba Dioum so wisely states: “In the end we will conserve only what we love; we will love only what we understand; and we will understand only what we have been taught.”