Sijimali Rising: A People’s Resistance To Cultural And Ecological Devastation

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 44

No. 2,

February 2024

By Shatakshi Gawade

Nestled in a cave atop Sijimali is the abode of Tij Raja, the supreme deity of the hill, who locals believe watches over them and the land. The hill is the source of over a hundred perennial streams that irrigate surrounding lands for agriculture; it hosts vital herbs that the Adivasi and Dalit communities here use in their healing practices, and biodiverse forests that support livelihoods. Known locally as Tijmali and in government records as Sijimali, the hill is part of a series of peaks, all of which support the biodiversity, and culture of the people of Odisha. And buried inside Tij Raja’s home, with the potential to destroy his very existence and land, is bauxite, the source ore for aluminium. After decades of lying quietly in the belly of Sijimali, bauxite mining was initiated in 2023 when the technology conglomerate Vedanta Limited was chosen as the preferred bidder by the Government of Odisha’s Steel & Mines Department.

Forty five per cent of the mining lease area of Sijimali is covered by forests. (Image for representational purposes. Photo: Rajesh Kallaje.

We The People

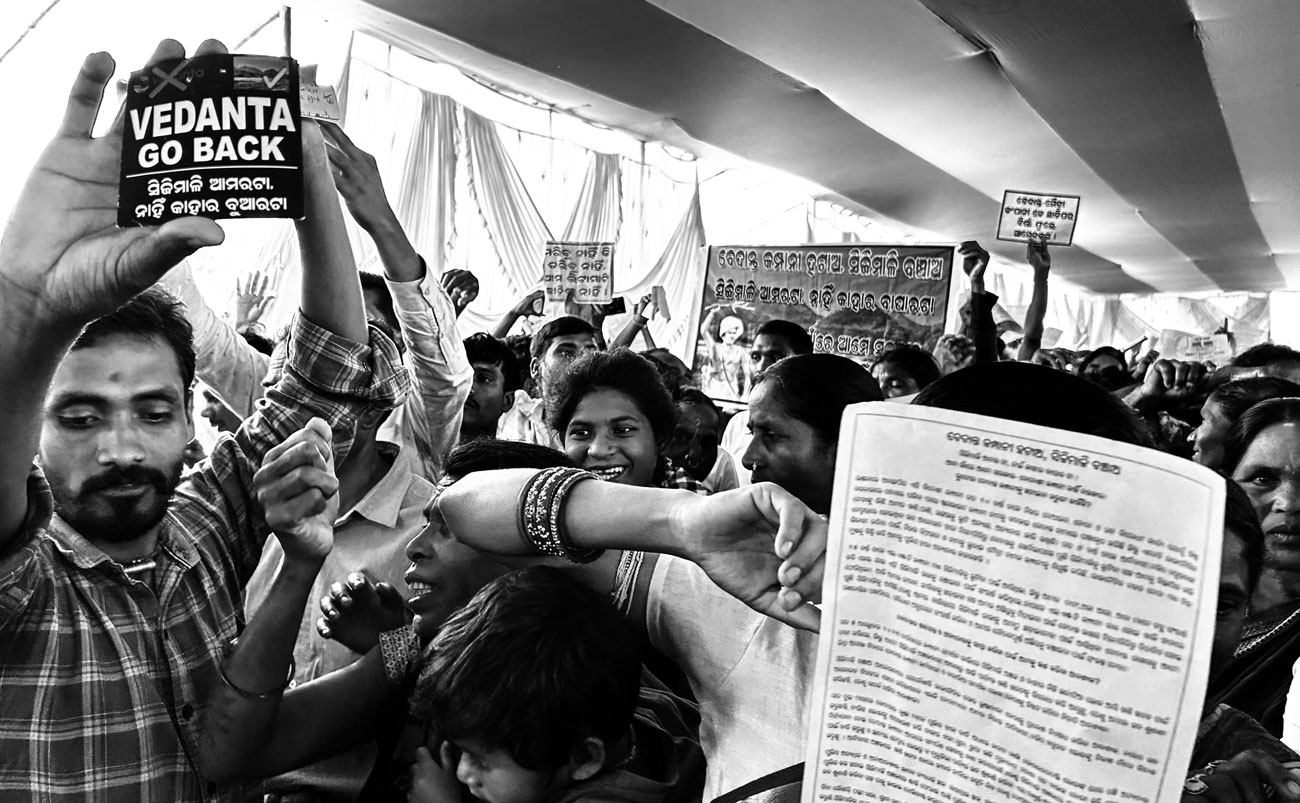

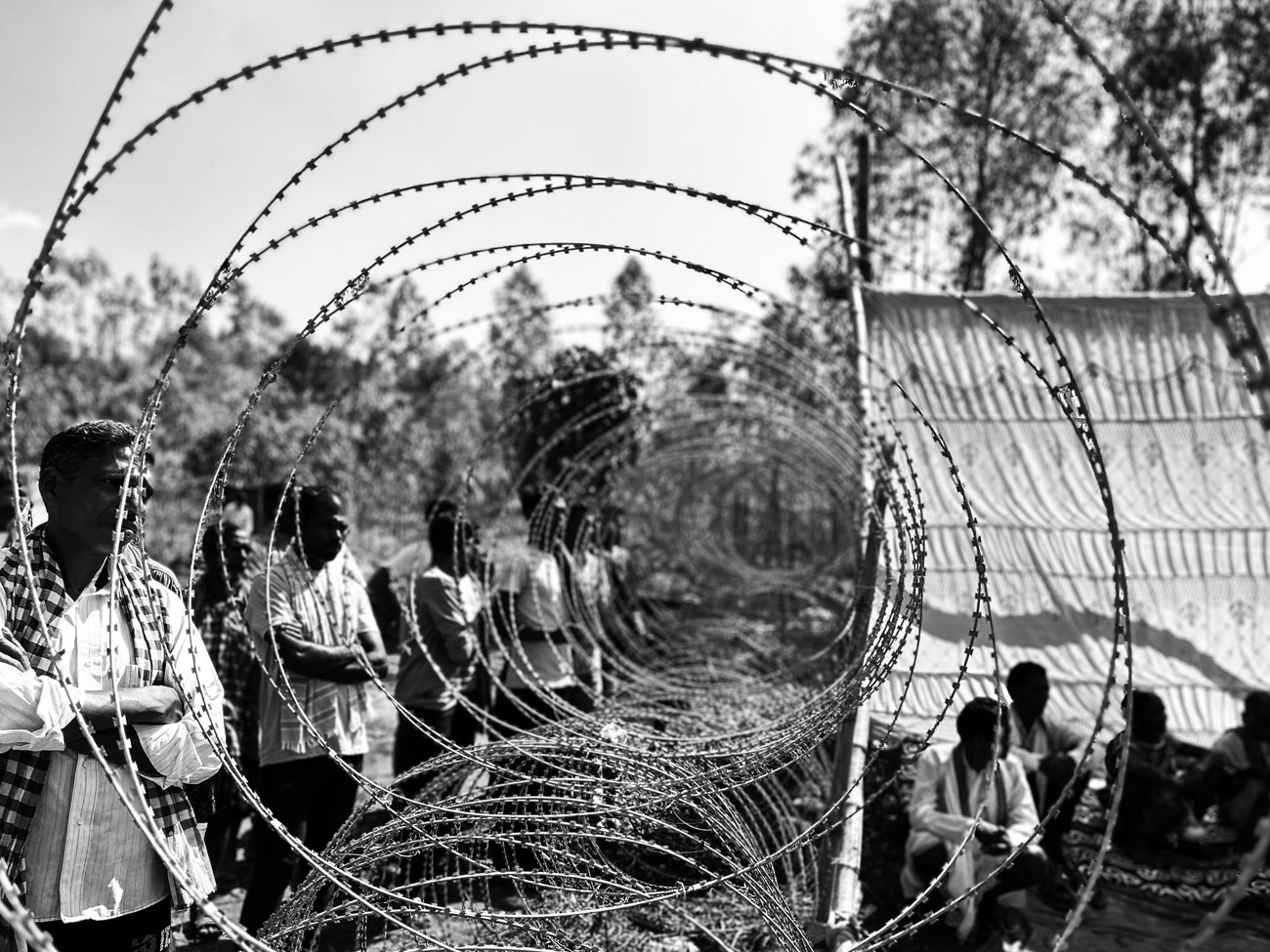

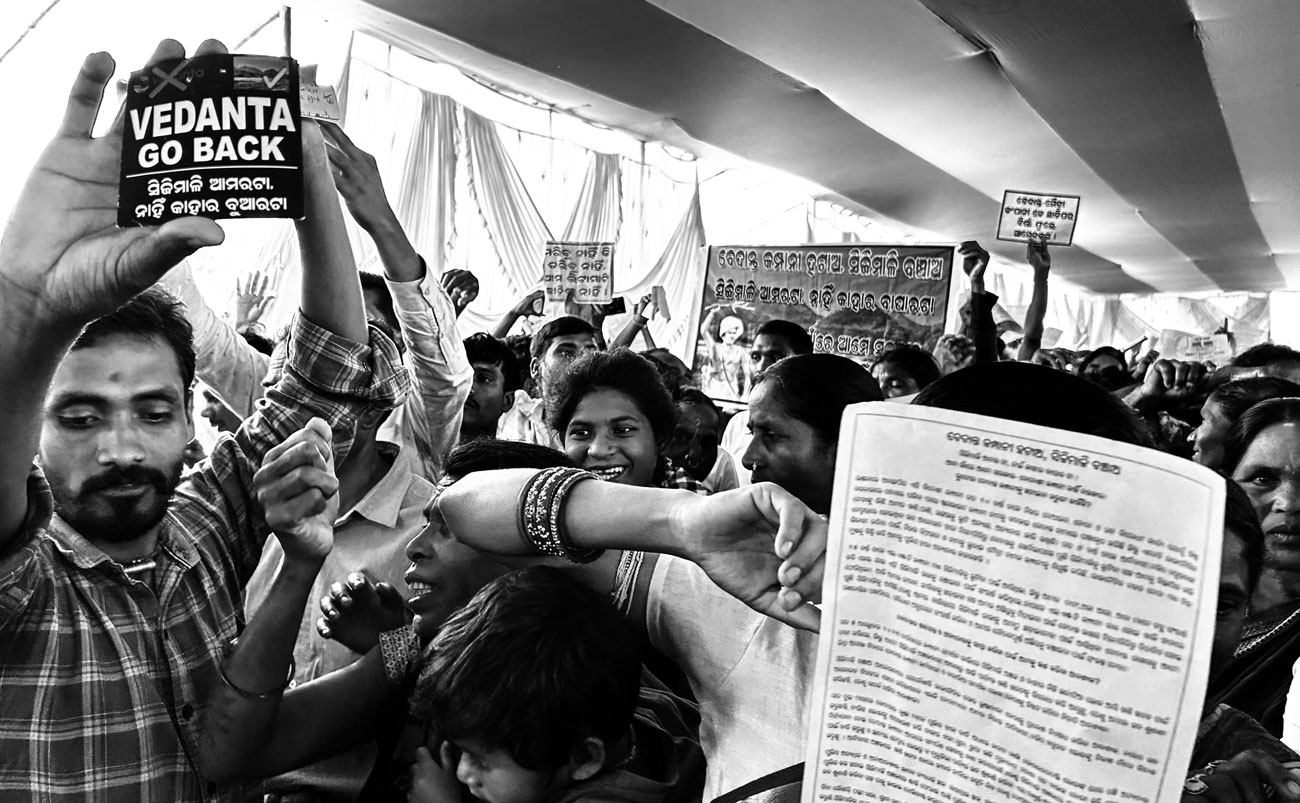

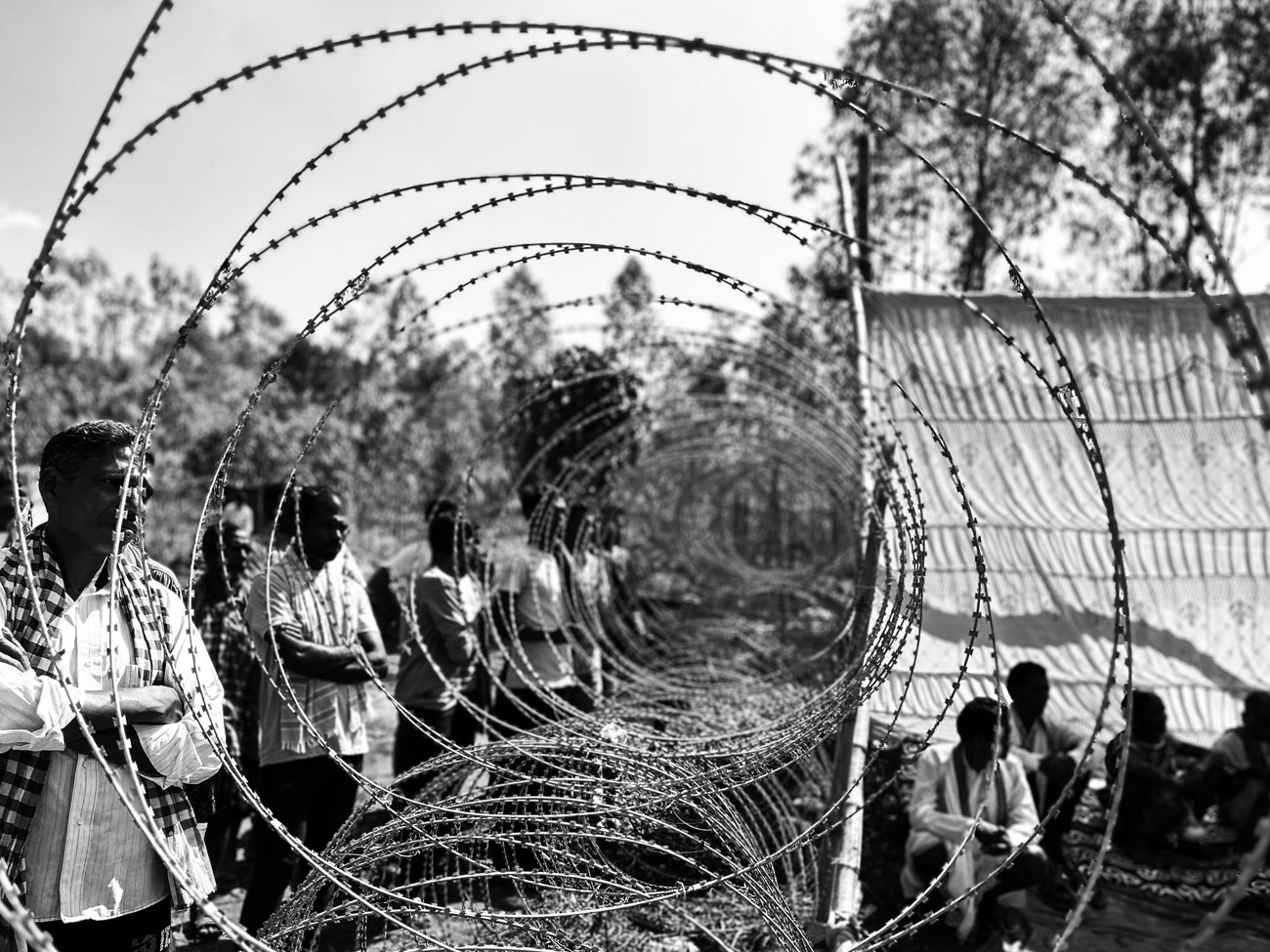

Since July 2023, villagers living in and around the mining lease area have resolutely opposed the bauxite mine, banding together to prevent access to their village or the Sijimali hilltop. Members from the villages of Sijimali have collectively demanded the cancellation of the mining lease given to M/S Vedanta Limited in July 2023, stating that: “Environmental clearance, if given, will completely destroy and shatter our ways of life, life-systems and our belief systems. We as Adivasi and Dalit communities will be pushed into permanent dispossession from our roots, i.e our lands, forests and streams, which are entwined with our everyday realities for generations.” As Gram Sabha meetings were held under the watch of armed police contingents, the community and experts were quoted as having objected to the coercion and intimidation.

Public consultations are a part of the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) process, while Gram Sabha consent proceedings are to be held as per the provisions of the Forest Rights Act (FRA). “Owing to recent regulatory changes, consent and consultations proceedings have been diluted. It is very hard to say what the legal mandate will be now,” said Radhika Chitkara, an Assistant Professor of Law at the National Law School of India University, Bengaluru, who has independently analysed the documents related to the Sijimali mine. She reiterated that the public hearings conducted in October in Sijimali did not uphold norms relating to free, prior and informed consent. “Given the environment in which the public hearings were conducted, with over 20 people in prison, several detained, and open-ended FIRs bringing within their fold several people, including one under the anti-terror law UAPA, there were apprehensions about whether people would raise their voice, when their public leaders and kin were being targeted. Despite all odds, the people expressed their objections very freely, and resisted unitedly.”

Ranjana Padhi, co-author of Resisting Dispossession: The Odisha Story, writes: “This region is extremely rich in natural resources. Both Adivasis and Dalits are dependent on cultivation as well as forest produce here. They have collectively challenged the illegality of the mining project. But because of the number of criminal charges foisted on them, it has become a risk for them to even travel to the district headquarters to draw the attention of the Collector or the press.”

Sharanya Nayak, a solidarity worker based in Koraput, shared that the women of the villages are constantly on the alert for any sign of the authorities out to detain the men of the community. But they are nevertheless determined to oppose anyone if they enter the village to detain the men, she said.

Prafulla Samantara, an anti-mining activist and Goldman Prize winner for his historic work in the Niyamgiri resistance, is unwavering about the importance of the resistance. “The forests are an integral part of people’s identity and livelihood here. They are crucial for clean air and water. Their destruction will be calamitous, and that is why there is a democratisation of the movement, with Adivasis and Dalits fighting shoulder to shoulder. The youth are also just as involved, as are the women,” he said. Samantara sees that if the area is mined, a new poverty zone will be created – only few people will make money, while the local population is displaced and dispossessed. “Since neighbouring areas of Sijimali are also either being mined or are about to be mined, the area will become barren. The cumulative effect will lead to socio-economic and ecological degradation. Our aim is to save the area,” he said with conviction.

Sharanya Nayak, a solidarity worker based in Koraput, shared that the women of the villages are constantly on the alert for any sign of the authorities out to detain the men of the community. Photo: Rajaraman Sundaresan.

The Mine In Figures

The Odisha government allocated the Sijimali bauxite mine, which spreads over 1,549 ha. of Odisha’s Kalahandi and Rayagada districts in the heart of the state’s bauxite belt, in March 2023 to Vedanta. This includes eight villages of Thuamul Rampur tehsil (Kalahandi) and 10 villages of Kashipur tehsil (Rayagada), which are dominated by a Scheduled Tribe population of Kondh and Parajas Adivasis, and Dom Dalit communities. Forty five per cent of the mining lease area is covered by forest, a mix of reserved as well as village forests.

Aluminium is being seen as the ‘metal of the future’ for its vast applications in industries such as electrical vehicles and renewable energy, infrastructure, transport, aviation and aerospace. Vedanta Aluminium, a business of Vedanta Limited, is reportedly India’s largest and among the world’s leading aluminium producers. Before Vedanta entered the scene, Larsen and Toubro had prospecting rights for Sijimali since the 1990s. According to a pre-feasibility report from 2020, they could potentially mine bauxite from Kutrumali hill, and they already had a prospecting licence for neighbouring Malipadar.

Friends of the Hills

The local fable says that Tij Raja is a friend of the people, Khandual Raja is an old, wise person, who will advise the people, and Niyam Raja looks over the laws of the land. People of Niyamgiri, along with praying to Niyam Raja, invoke Tij Raja. People of Sijimali invoke Niyam Raja, in addition to Tij Raja. There is a strong cultural connection between the people of these hills. Even physically – a two-hour walk through the forest will take one from Sijimali to Niyamgiri. And that is why people from these neighbouring villages are gathering to help with the resistance at Sijimali.

(Shared by the shaman of Niyamgiri with Rajaraman, a student of Indigenous movements and an Odisha special correspondent with Samadrusti media, Bhubaneswar.)

“People know that if Sijimali gets mined, it won’t be too long before the neighbouring peaks of Batlingmali, Khandualmali, Kutrumali, Majingmali and Sasubaumali are also mined and destroyed,” said Rajaraman.

Landscape And Biodiversity

The dry deciduous Sijimali forest has several riparian forests along its streams. Scats and spoor of small-clawed otters, one of only three otter species in India, mark the banks of almost all perennial hill streams of southern Odisha. Kalahandi and Rayagada are elephant habitats, with elephant presence observed in the locality of the identified mining area.

Dr. Randall Sequeira, who has worked in the region for the last six years on different traditional healing practices, has observed the interaction of the community with the landscape and its biodiversity. “The plateau on top of Sijimali is perfect for some unique plants, which traditional healers use in their practice. It is also used by the Kondh Adivasis for grazing their cattle,” he shares. Sijimali supports the Adivasis’ Sacred Groves, which are the home of their gods and goddesses. While their main Goddess is the Earth Goddess Dharani Penu, each village also has 15-20 deities dotting the hill, which are worshipped before sowing and harvest season. Some of these deities are really old trees, some are traditional border marks, and some are rocks. “The Adivasis believe that any harm to these deities will anger the gods,” said Dr. Sequeira.

The baseline study for the draft EIA was conducted in summer (March to May). However, such studies need to be conducted in other seasons, to get a clearer picture of water flows, biodiversity, and weather patterns. Significantly, the draft EIA by experts and locals made little mention of the sacred caves in the area, an integral part of the belief system and culture of Sijimali’s people. The analysis also identifies lacunae, including the lack of groundwater and aquifer studies.

As Gram Sabha meetings were held under the watch of armed police contingents, the community and experts were quoted as having objected to the coercion and intimidation. Photo: Rajaraman Sundaresan.

Nayak rues the fact that there is no law to understand and assess the loss of the ‘sacred’ and its centrality to the people’s ways of life. “And so while this forms the essence of why Adivasi people resist mining, it is dismissed as irrelevant to any form of impact assessment, whether social or environmental,” she says.

The Impacts

Opencast bauxite mining involves the creation of a massive pit, where layers of soil and earth are stripped and excavated to obtain the ore. The increase in mining operations in Odisha have led to forest loss – Kalahandi lost over 20 per cent of its forest cover and Rayagada, along with Koraput, recorded the highest loss, from 2001 to 2019. Sijimali is located in these districts.

Areas that undergo opencast mining undergo extensive and sudden landscape changes, such as habitat fragmentation. While the mine may create jobs in the short-term, the ecological value of land and its ability to sustain people in the long run will be greatly diminished. Across India, mines are often located in eco-sensitive zones, such as the Western and Eastern Ghats, which are the source of river systems. These lands are often occupied by the poorest and most marginalised communities.

Opencast mining causes air, water and soil pollution, during the operation of the mine, and for several years after mining operations cease. Blasting, drilling, loading and unloading, crushing and transportation add particulate matter, oxides of nitrogen and sulphur dioxide to the air. Inexplicably, the draft EIA reports that “There will be no discharge of wastewater outside the lease area”. However, in an age of extreme climatic events, rainwater could conceivably drain through ore piles, turn acidic, and transport heavy metals away from the mining area, risking surface and groundwater contamination. Since bauxite is porous, hundreds of streams originate in the Sijimali hills; these streams flow into two rivers – Nagavali and Vamsadhara, which are vital resources for agriculture in Odisha and Andhra Pradesh. The metal-carrying water could affect aquatic biodiversity in even far-off waterbodies.

Since July 2023, villagers living in and around the mining lease area (MLA) have resolutely opposed the bauxite mine, banding together to prevent access to their village or the Sijimali hilltop. Photo: Rajaraman Sundaresan.

On Legalities

Prof. Chitkara shared that the project was still at different stages of clearances, yet the project proponent has applied for the mandatory Environment Clearance under the Environment (Protection) Act, 1986, and Forest Clearance under the Forest (Conservation) Act, 1980. Interestingly, the Project Screening Committee had, at the first stage itself, rejected the proposal on 19 grounds, she shared, adding that the Environment Advisory Committee raised the issue of the proximity of the mine to the proposed Karlapat Wildlife Sanctuary.

Sijimali is the source of over a hundred perennial streams that irrigate surrounding lands for agriculture. Along with deciduous forests, the hill also has riparian forests along its streams. Photo: Rajaraman Sundaresan.

In conclusion Prof. Chitrakara opines that: “As far as a legal recourse is concerned, it is very challenging at this stage since people have very limited rights of participation. Clearances for such projects are guided by executive instruments, involving various Expert Committees – which review the project according to their mandates. It is crucial that these bodies discharge their duties according to the precautionary principle, and take into consideration the objections raised by affected communities.”

Shatakshi Gawade is an Assistant Editor at Sanctuary Asia. She has worked with mainstream media, as a freelancer, and as a researcher, campaigner and communication consultant with organisations that focus on the environment.