The Heir of the Queen Mother

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 37

No. 4,

April 2017

By Ashish Thakare

It has been almost two years, but I still remember it like it was yesterday. The sizzling summer temperatures did not wither our commitment as we patrolled the Kosambi beat, Awadgaon round of the South Bramhapuri Range. I was the first to spot the large tiger on the other side of the Ghosikhurd canal. On my instructions, the driver eased the engine and gradually made his way down as unobtrusively as possible. Not surprisingly, the alert tigress noticed and kept an eye on us as she slowly moved away. I identified her as T-8 and knew her three cubs would be nearby. The set-up camera-trap in that beat had regularly captured this tigress and her family hunting cattle.

I picked up my DSLR, placed my bean bag on the window, and began photographing her. As we approached a bridge we momentarily lost sight of her, but on crossing over, spotted her again, near a water tank. She then began walking confidently toward us in the direction of the canal. We reversed to allow her to cross the bridge constructed across the Ghosikhurd canal by the Forest Department for the safe passage of wild animals. Having crossed, the cat disappeared into the forest. Nothing could have demonstrated the need for well-designed passages across canals better. We hung around for a while, listening to the mother call out to her cubs, and then left the family in peace.

I followed T-8’s movements regularly, often through the camera-trap images shown to me by the ever-active Kosambi beat guard Zade, who had made it his mission to keep track of and protect the cat family.

Occasionally, I would receive a call from him confirming a sighting and one such revealed the three cubs gambolling near the Ghosikhurd canal. On our arrival, the mother peeked out from a nearby bush as if to let us know she was around and warning us to keep our distance. This was special, as it was my first sighting of a tigress with cubs.

Night encounters

After May 2015, we failed to obtain any camera-trap images of the family from the canal side of the forest, though occasional, unconfirmed reports from other parts of the forest would come through. Then, on a night-patrol in winter, near the canal, a slight movement caught my eye and in the beam of my torch, and to my utter delight, there they were… ‘my’ three sub-adult tigers, which the forest guard said were T-8’s cubs. We stayed quiet, observing them for two hours, with the young ones showing no sign of shyness. At one point, they actually approached our vehicle! I saw that one was a female and felt like a doting grandparent visiting his little ones after a long gap. I really did not want to move away. The next morning, my staff placed barricades to prevent human disturbance to the T-8 family.

Camera-trap images confirmed that the family had moved to the adjoining Awadgaon waterhole, deeper in the forest. A few days later I visited the waterhole one evening and was heartened to see a near-perfectly camouflaged tiger watching my every move. As darkness fell, we headed back, only to be presented with a view of two sub-adults near the waterhole. Looking in the direction they were staring, I saw the mother, T-8, who casually walked away towards the forest, followed by her obedient cubs. This was a careful mother, I thought to myself, protecting her cubs in the best possible way by teaching them to avoid humans.

It was a magical moment. Starting the vehicle to make our way back, to our absolute surprise, there was T-8 again, this time standing in our headlights, just 15 m. from us. Incredibly, her cubs too emerged; the four walking right up to our vehicle, then crossing over to the darkness of the forest on the other side. For some inexplicable reason we had been trusted. I shut my eyes and thought to myself ‘they were amber flames against the ground’. I will never forget that moment, as much for the sighting as the trust the mother seemed to display in us.

By early 2016, T-8’s cubs had started hunting along with ther mother. Subsequently, the Forest Department decided to radio collar the sub-adults and study their dispersal along with the Wildlife Institute of India (WII).Photo Courtesy:Ashish Thakare

Tracking tigers

The family became my family. As I went about performing routine duties as the Deputy Conservator Forests of the Bramhapuri division, I kept track of their daily movements. By early 2016, the cubs had begun hunting with their mother. I even once saw the female cub charging a wild pig.

The Bramhapuri Forest Division is densely occupied by tigers and leopards. I was therefore worried about the ability of the sub-adults to find territories for themselves when separated from their mother. In the summer of 2016, we decided to work with the Wildlife Institute of India (WII) to study their dispersal by radio collaring the sub-adults.

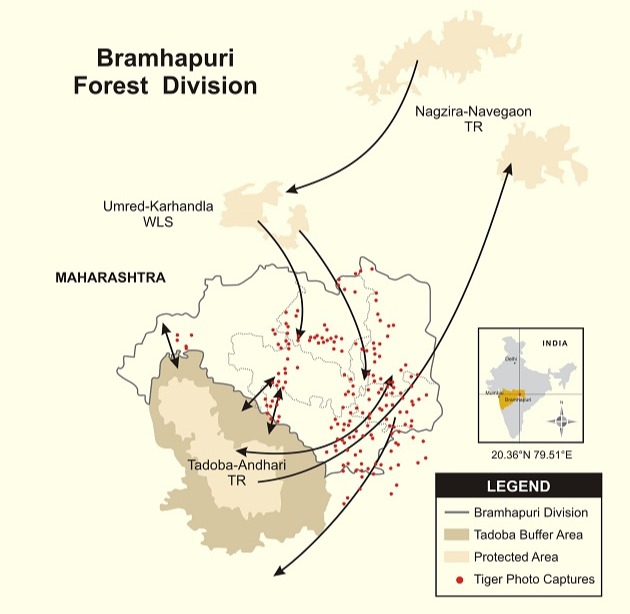

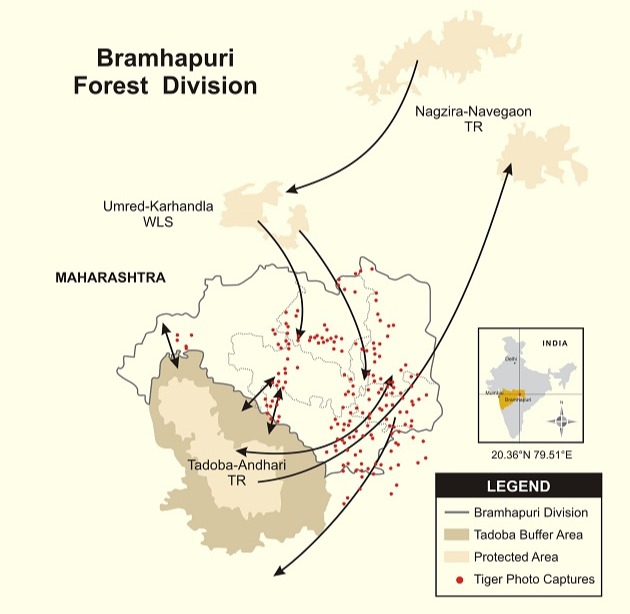

Bramhapuri is part of a vital corridor between the Tadoba Andhari Tiger Reserve (TATR)-Umred Karhandla Wildlife Sanctuary, TATR-Nagzira-Navegaon Tiger Reserve and TATR-Indravati Tiger Reserve. Source: Bramhapuri Forest Department

I headed one of the tracking teams and acting on a forest guard’s information, we approached a waterhole on foot in Halda beat of South Bramhapuri range, where we found fresh pugmarks. To avoid any risk, we immediately got into our vehicles and moved away from the area to the adjoining agricultural fields. Lo and behold! There was a tiger looking at us some distance from the field! We followed the magnificent cat, but could not get close enough to dart it. We returned the next day with veterinarian Dr. Parag Nigam and were fortunate enough to successfully collar the sub-adult female and one of the sub-adult males. We would now be able to track their movements from satellite data and ground staff.

A month later, camera-trap images of a male tiger turned up from Gadchiroli’s Wadsa Forest Division. Data analysis confirmed it was T-8’s sub-adult male. He had travelled 50 to 60 km. all the way to Wadsa, crossing the Wainganga river in the process. Unfortunately, we have not received any news of this male since then.

In August, I was at a human-animal conflict training camp at the Kerala Forest Research Institute in Thrissur, when I learnt that the collared male sub-adult had been killed by another tiger, not far from the forests in which his mother had brought him up. The young female was doing well, having taken over the territory of her mother, who had shifted to another compartment. We kept hearing of cattle kills in the young tigress’ territory, and people began to see her openly every second day in the villages of Kosambi, Murpar, Saigaon, Belgaon and Kalamgaon.

On September 9, 2016, the young female injured a young boy near Belgaon next to compartment no. 167. On September 23, 2016, she killed a woman in Saigaon and dragged her from the field to forest compartment no. 207. More cattle kills were reported from nearby villages, with one taking place in the presence of a farmer. That seemed to be the last straw, triggering pent up anger and fear in locals from the nearby villages.

We had no choice. The Chief Wildlife Warden issued orders to capture her with help from Tadoba’s expert veterinarian, Dr. Khobragade and Dr. Prashant Deshmukh of the Wildlife Conservation Trust (WCT). By now the monsoon had set in and the forest was difficult to access safely. We called for reinforcements in the form of trained elephants. Eventually, Dr. Parag Nigam and Dr. Bilal Habib from the WII pitched in and we successfully darted the cat. Her collar was changed by Dr. Habib, and on instructions from the Chief Wildlife Warden, she was released in the Chaprala Wildlife Sanctuary, the very same day to keep her duress to the minimum.

But since then, tracking her has not been possible as the satellite did not transmit data. Our only option was to hope for ground information through the VHF receiver. Hopefully, this anomaly will soon be rectified.

As anyone can imagine, it’s extremely difficult to monitor wild tigers, particularly if they are surrounded by populated villages. It is my hope that the Chaprala Sanctuary, which has a healthy population of herbivores, can offer T-8’s daughter sanctuary.

As I write this piece for Sanctuary Asia in March 2017, news comes in of T-8 having delivered still more cubs. I will follow them, protect them, but worry about their survival in such a conflict-ridden environment.

The author was witness to T-8 crossing a bridge constructed across the Ghosikhurd canal by the Forest Department for the safe passage of wild animals. Well-designed passages across canals such as these are invaluable for a tigress raising cubs on her own. Photo Courtesy:Ashish Thakare

Brahmapuri – A Vital Tiger Corridor

Bramhapuri is one of the three divisions located in the northeastern part of Chandrapur district (20036’55.38”N 79051’22.08”E) at an average elevation of 230 m. above sea-level. This forms part of the Chandrapur Forest Circle, touching the buffer of the Tadoba-Andhari Tiger Reserve (TATR) to the west and the Gadchiroli Forest Circle to the east. This is a part of a vital corridor between TATR-Umred Karhandla Wildlife Sanctuary, TATR-Nagzira-Navegaon Tiger Reserve and TATR-Indravati Tiger Reserve.

The Bramhapuri Forest Division spreads across 1,187.86 sq. km. of which 986.21 sq. km. is with the Territorial Division and 201.65 sq. km. with the Forest Development Corporation of Maharashtra (FDCM). The territorial area is further divided as Reserved Forest (64,395.109 ha.), Protected Forest (33,445.36 ha.) and Unclassified Forest

(780.98 ha.). The division has six ranges, 21 rounds, and 92 beats. The area also comprises 608 villages, of which 356 villages abut the forest.

The diversity of fauna documented includes tiger, leopard, sloth bear, sambar, nilgai, chital, gaur, wild dog, hyena, wolf, small Indian civet, jungle cat, honey badger and jackal. The population of tigers is relatively high. Reptiles here include rat snakes, Russel’s vipers, checkered keelbacks, Indian rock pythons and common monitor lizards.

In 2014-2015, the Wildlife Conservation Trust camera-trapped 27 adult tigers, 11 males and 16 females, plus three cubs. At the same time, between 80 to 85 leopards were also camera-trapped. In February 2016, as many as 47 different tigers were identified, 15 males, 20 females and 12 cubs.

It is the presence of human settlements and farmlands in the vicinity of so many large carnivores that is the root cause of conflict. And reducing this conflict is a key priority for wildlife managers.

| Year |

No. of humans killed |

No. of humans injured |

No. of cattle killed |

No. of cattle injured |

No. of crop damages |

| 2013-14 |

1 |

34 |

555 |

18 |

733 |

| 2014-15 |

4 |

30 |

556 |

24 |

732 |

| 2015-16 |

3 |

105 |

880 |

34 |

3,412 |

| 2016-17 |

5 |

36 |

602 |

12 |

2,164 |

| Total |

13 |

205 |

2,549 |

88 |

7,041 |

Open Wells

Spread over 1,100 sq. km., the buffer zone of the Tadoba-Andhari Tiger Reserve encircles Chandrapur and Brahmapuri and houses as many as 79 villages. The open wells that water these villages are often without barriers and several animals have lost their lives by accidentally falling into them. In one particularly tragic incident in 2011, a four-year-old tiger plunged to its death in an open well near Ratnapur village in the Brahmapuri forest division that adjoins the tiger reserve. That well, like most others, did not have a parapet wall and was concealed by thick shrubs. Over the years, such incidents more often than not take place at night, when chasing prey. Often this results in serious injuries that lead to death by drowning, after hours of desperate swimming to stay alive. Even when an animal is rescued, it may succumb to injuries sustained during the fall. What is more, many wells have narrow mouths, making rescue operations extremely difficult. The Tadoba-Andhari Tiger Reserve Conservation Foundation extends monetary support to Eco-Development Committees (EDCs) in buffer villages for individual and community development. A chunk of this is now earmarked for the construction of parapet walls for open wells. Copyright: The Tadoba Inheritance