The Last Stand Of The Little Florican

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 41

No. 12,

December 2021

By Nigel Collar

There is nothing like it. It is a monsoon apparition. Suddenly, as the grasslands of western India revive under the rains, there is an unexpected surprise. A black-and-white creature flutters vertically from the tall grass and instantly drops back out of sight. It does it again, and again. Up it goes, thrice the height of the vegetation screening it, with a flicker of wings and a little dry rattle at the apex, then straight down, wings folded, yellow legs outstretched – and gone. It takes less than two seconds. He keeps doing this all day.

He is a Lesser Florican or, as I prefer, Little Florican, because there is nothing lesser about him. In his black plumage, white-edged wings and gold-spangled back, he is a miracle of dandyism, the essence of dude. His moustaches twirl behind his head in wavy exuberance. You cannot find his like in the grasslands of North or South America, Europe, Africa or East Asia. He is, indeed, incomparable. If you want to see him and his extraordinary leaping display, there is nowhere in the world except India. But soon, there will be nowhere.

Male Lesser Floricans put on a spectacular display during the breeding season; the birds jump about two metres into the air, fluttering briefly above the grass, producing a croaking sound to attract a female. In a day, they average about 600 jumps!

Photo:Ashok Chaudhary

A HAUNTING PAST British ‘sportsmen’ used to shoot him when he was leaping through the air, because that was the only time they could find him. Their utter disregard for the code that proscribes killing animals in the breeding season led to serious prophecies of his extinction. Sálim Ali even witnessed such behaviour after Independence. But the British did a much worse thing for the florican: they called its grassland habitat ‘waste land’, land on which economically productive enterprises were to be encouraged. Regrettably, India has allowed this fallacious, prejudiced designation to undermine its conservation priorities right through to today. As a result, grasslands have been the most difficult wildlife habitats in India to defend. And everywhere they have disappeared – under the plough, under pasture, and under ‘progress’.

Perhaps it is because you only really get to see the Little Florican, a bird practising to be a skyrocket, as a brief, distant glimpse of fluttering feathers, that so few people noticed how badly it has been faring. Out of sight is out of mind – but this is how the floricans like it: their evolutionary circumstances mean they do not want to be noticed. They cannot roost in trees like storks or out in marshes like cranes, and they do not possess the formidable bills of storks and cranes to defend themselves.The floricans, like all bustards, have come to depend on hyper-vigilance, immense wariness and intricate camouflage for their survival. The females spend their lives pretending to be bunches of dry grass stems; and, but for the three months of the year when they assume their finery to compete for the females’ attention, the males do too. Studying such birds year-round, learning where they go, deducing what they need, is consequently a challenge that is still awaiting its champion.

Female Lesser Floricans have brown-patterned plumage and are often harder to spot amidst the grasslands.

Photo:M. Raghavendra

Even so, over two centuries of observations since the time of Dr.Jerdon, ornithologists have pieced together enough of the biological jigsaw to have a rudimentary picture of the florican’s life history. As a grassland species, it is too large to feed on seeds, and subsists on mid-sized to large invertebrates. It nests on the ground, with all duties falling to the females, which lay up to six eggs. It is a short to medium-distance migrant, its populations moving back and forth within the subcontinent, north-west to breed, south-east to winter, but rainfall seems to dictate its movements, so that in dry years it can stay put in central India or, in wet ones, pitch up far beyond its normal range, for example near Lahore or in the Nepali terai.

All these things – its size (however ‘little’ it is!), habitat, diet, nesting habits, opportunistic migrations and of course that immense wariness – set it at a disadvantage in the modern world. Its size makes it attractive to poachers, which has always been a problem. Its habitat has greatly diminished in both extent and quality. When it takes to cropland to breed, as it does around Ajmer in Rajasthan (evidently because the males find it sufficiently analogous to grasslands in the low lush green vegetation and there is nowhere else to go), the insect supply shrinks, first by the ploughing that creates the crops and then by the spraying that sanitises them. This is supremely bad for chick-rearing – you need a glut of grasshoppers to bring five or six youngsters to independence – and, if the crop comes to mechanical harvest before any young can hatch or indeed fly, it is a likely death sentence for any ground-nesting species. Worse still, if the monsoon is uneven, the birds that follow it may lose vital breeding years because they cannot find sufficiently well-watered patches of grassland. And, finally, if the patches of grassland they do find are too small, they will not be able to cater for the birds’ risk-averse need for seclusion. Recent research confirms it: floricans favour large areas of grassland.

Male Lesser Floricans put on a spectacular display during the breeding season; the birds jump about two metres into the air, fluttering briefly above the grass, producing a croaking sound to attract a female. In a day, they average about 600 jumps!

Photo:Gobind Sagar Bhardwaj

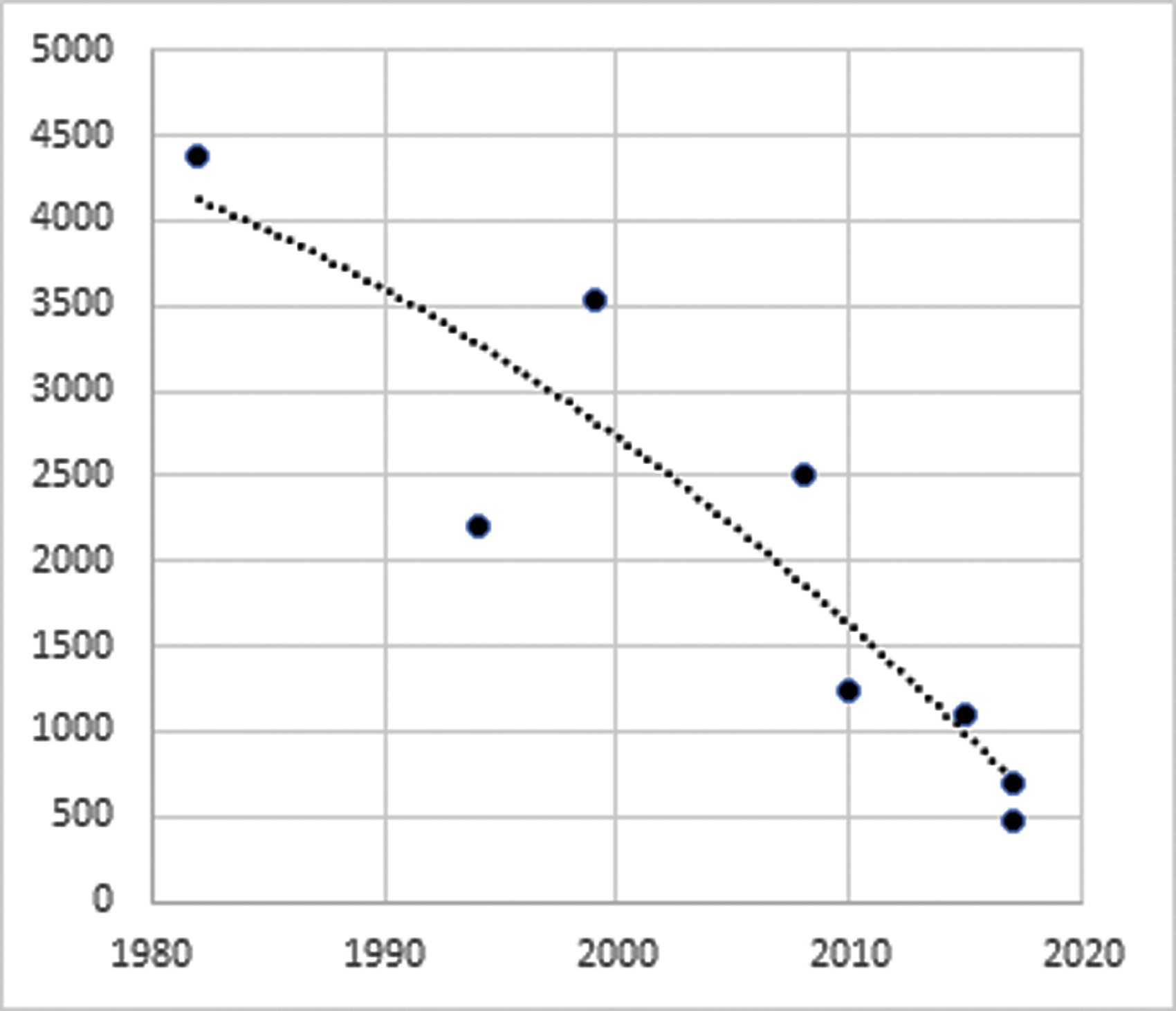

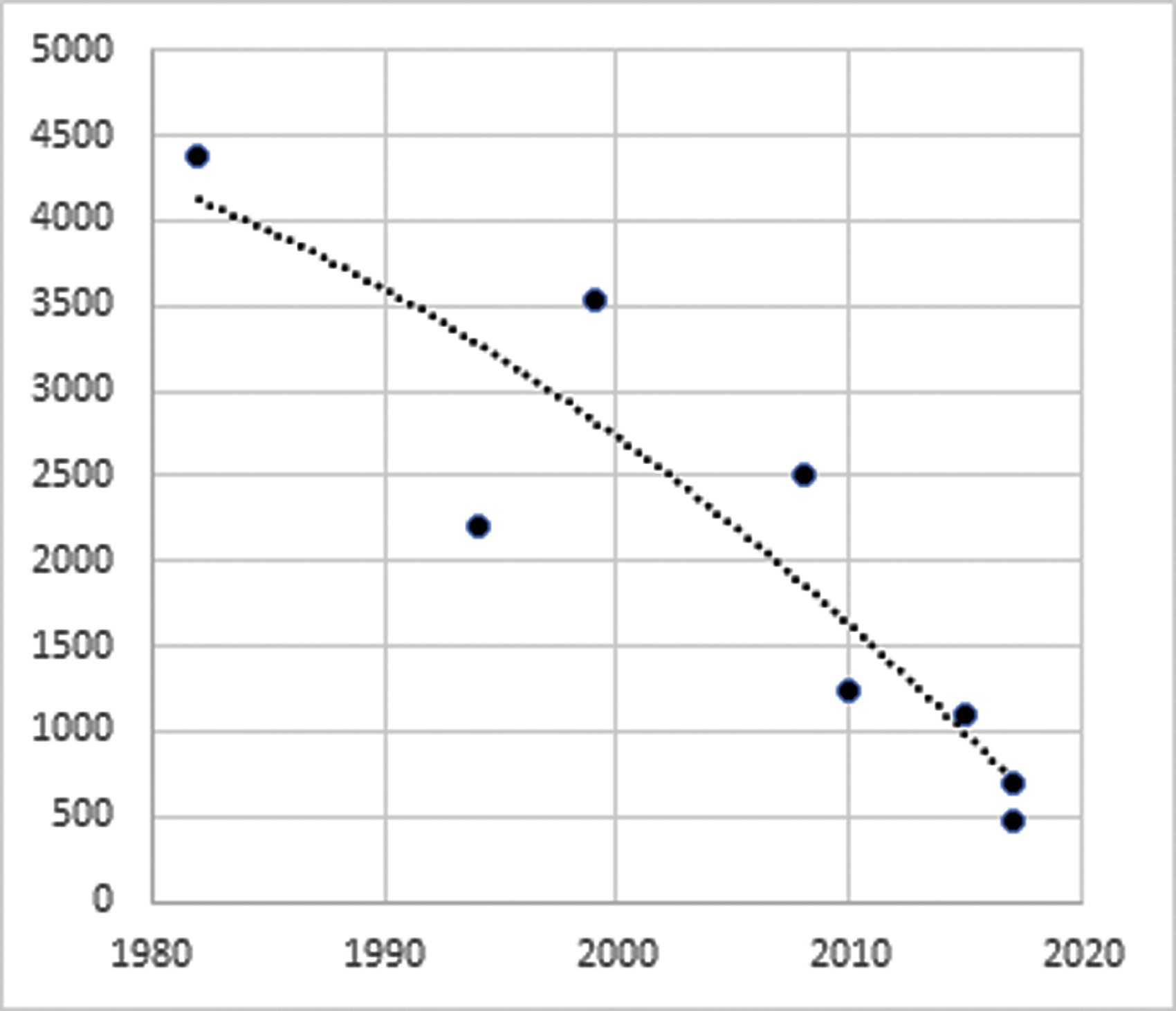

GOING, GOING, GONE? Clearly the worst of these influences is habitat loss. Every other influence, apart perhaps from the poaching, follows in its wake. Sálim Ali realised this, and created two ‘Lesser Florican Reserves’ for the species in Madhya Pradesh. These should have helped, but without proactive management, over time, their value to the floricans has been washed away like sandcastles in the tide. In any case, the species needed much more help than even two well-run reserves could have given. After a baseline assessment of 4,374 displaying males back in 1982, Ravi Sankaran conducted repeated samplings across the breeding range in Rajasthan, Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh and Maharashtra, encountering a wild fluctuation attributable to drought but plotting an inexorable decline. When in 2010 biologists attempted to replicate his 1999 survey, which estimated 3,530 males, the decline they documented equated to a population of only 1,246 males, while a survey in 2014-2015 yielded an estimate of 1,091, a quarter of the 1982 figure. Then, in 2017, a superb investigation organised by the Wildlife Institute of India (WII) under the scientific leadership of Sutirtha Dutta, with the participation of the Bombay Natural History Society (BNHS), The Corbett Foundation (TCF) and state Forest Departments, resulted in the shocking finding that the number of males in that year was below 500 (although 700 was also quoted informally).

A graph of the population trajectory of the Lesser Florican in India, from 1980 until 2020. This now Critically-Endangered bird is on the brink of extinction due to the degradation and loss of its grassland habitat.

Photo Courtesy:Nigel Collar

Whether 500 or 700, a line fitted to these figures predicts extinction for the Little Florican within the next five to ten years. If ever there was a time to hit the panic button, mid-2018, when Dutta’s report appeared, was it. Astonishingly, however, nothing has changed. Repeating and extending the many recommendations that had never been implemented since the species went on the International Red List in 1988, Dutta’s report called for new, strictly patrolled conservation areas, appropriate grassland management and consolidation, florican-friendly (organic) practices in areas where the species occupies crop lands, prevention and mitigation of florican-hostile infrastructure and other developments, networks of sympathisers, outreach programmes, dog controls, and more research. BNHS, already operating an excellent community programme in the farmland around Ajmer with BirdLife’s support, has not yet found the funding to broaden the scope of its work. TCF, likewise already undertaking similar work at Abdasa and Mandvi in Kutchh on behalf of both the florican and the Great Indian Bustard, has continued as best it can. Three state governments have opted for captive breeding but taken no serious steps to address the real issues.

The author was awarded the Sálim Ali Award for Nature Conservation in February 2009.

Photo Courtesy:BNHS

A CALL TO ACTION The most startling absence of action concerns the area around Velavadar, including ‘Blackbuck’ National Park, in Gujarat. Because it has a protected grassland as its focus and unprotected grasslands in adjacent terrain, this proves to be the single most important site for displaying floricans on the planet. An intensive programme of habitat defence, creation and consolidation is desperately needed to build up the population there – all the more so because of rapidly escalating developments in the region, including solar farms. The park itself hosts thousands of blackbucks, an iconic but secure species, Least Concern on the IUCN Red List, and an obvious measure is to manage the area at least as much for the florican as for any other wildlife, and preferably to rededicate it primarily for the florican.

A Lesser Florican male shows off his brilliant breeding plumage – entirely jet black except for a white covert on his shoulder and white band on his upper back, with black plumes with flattened broad tips sweeping back from his head.

Photo:Surendra Singh Chouhan

Authorities at national and state levels have been sleeping through the alarm bells ringing by their bedsides for two decades now, never louder than since 2018, and it is time to wake up and panic. We must marshal our human and financial resources immediately. We need a clear plan and an emergency committee to coordinate its implementation.

BirdLife and the IUCN SSC Bustard Specialist Group stand ready to support the effort. But this is India’s battle to win – and it is India’s reputation at stake.

The desperately urgent parts of the plan to secure the future of the Little Florican are right under our noses. Some recommendations:

• Start a major conservation programme at Velavadar

• Review all other grassland reserves, which could be repurposed for floricans

• Quadruple BNHS and TCF community work in Ajmer and Kutchh respectively

• Investigate the many potential florican areas identified in Dutta’s report

• Restore the florican reserves, Sailana and Sardarpur, in Madhya Pradesh.