The Rise Of The Mangrove Jackals: The Future Of Urban Wildness

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 45

No. 6,

June 2025

In the shadowy, shifting world of Mumbai’s mangroves, a quiet drama unfolds – one that few city dwellers even know exists. At the heart of this urban wilderness lives an unexpected predator: the golden jackal. Long overshadowed by larger carnivores, these elusive creatures have carved out a surprising existence in the brackish, tide-washed forests that hug the city’s edges. Nikit Surve takes you deep into the tangled roots and hidden clearings of Mumbai’s mangroves, where science, folklore, and conservation efforts converge to reveal the incredible story of the golden jackal’s survival – and what it means for the future of coexisting with wildlife in a rapidly urbanising world.

Through the tangled maze of pneumatophores, a sudden glint caught my eye – an unexpected pair of eyes peering back at me. A golden jackal Canis aureus. Just as startled by me as I was by it, the animal stood motionless for a moment in the mangroves of Pirotan, a small isle off the coast of Gujarat.

Golden jackals are no strangers to the Indian subcontinent. They roam across India and stretch into Pakistan, Bhutan, Myanmar, and Nepal. But here? In the salty, shifting tides of an intertidal mangrove? I hadn’t expected to find them in such an unforgiving, brackish world.

That night, as our team set up camp, guttural howls echoed through the dark – low, haunting calls that seemed to affirm what I’d seen. At first light, eager and restless, we combed the beach. The tide had pulled back just hours earlier, leaving behind soft, wet sand – and tracks. Distinct pugmarks: two adults, maybe a few pups. But a doubt lingered. Were they jackals? Or just stray dogs?

We pressed on, wading carefully through the swampy undergrowth, eyes scanning every corner. The mangroves squelched beneath our boots. Then, just 20 minutes in – we saw them. Still. Silent. Watching.

Their eyes met ours – wary, intelligent, and utterly wild. There was no mistaking them now. Golden jackals, living in the heart of the mangroves.

Golden jackals thrive in Mumbai’s tidal mangroves – a salty, shifting world that tests even the most adaptable. Proven survivors, they navigate this unstable wilderness – and encroaching city – with quiet resilience. Photo: Yogesh Durge/Sanctuary Photolibrary.

Will Adaptabilty Alone Be Enough?

The golden jackal wears many faces across its range – 14 subspecies, each adapted to its own corner of the world. In India, four subspecies of Canis aureus are found, but they remain poorly studied. Of all the wild canids in the country, golden jackals are the most adaptable, thriving in dense forests, windswept grasslands, farmlands, and even the chaotic edges of cities.

Their story is one of resilience – but also of reckoning. Once listed under Schedule II of the Wildlife (Protection) Act, golden jackals were moved to Schedule I in 2022, a belated recognition of their ecological role and the pressures they now face.

Mumbai’s relationship with the golden jackal goes back more than a century. Between 1904 and 1918, naturalists like Kothari and Chhapgar documented jackals weaving through the heart of the city, even being chased by free-ranging dogs from Charni Road Station to Marine Drive. In those days, they roamed freely in the southern reaches of the island city – in Colaba, near St. Xavier’s College, and beyond.

But that version of Mumbai is long gone. What remains is a sliver of wildness tucked into mangrove belts – one of the few urban sanctuaries for golden jackals. In a metropolis that’s grown taller, louder, and faster, their quiet persistence in the muddy, green edges of the city feels almost defiant.

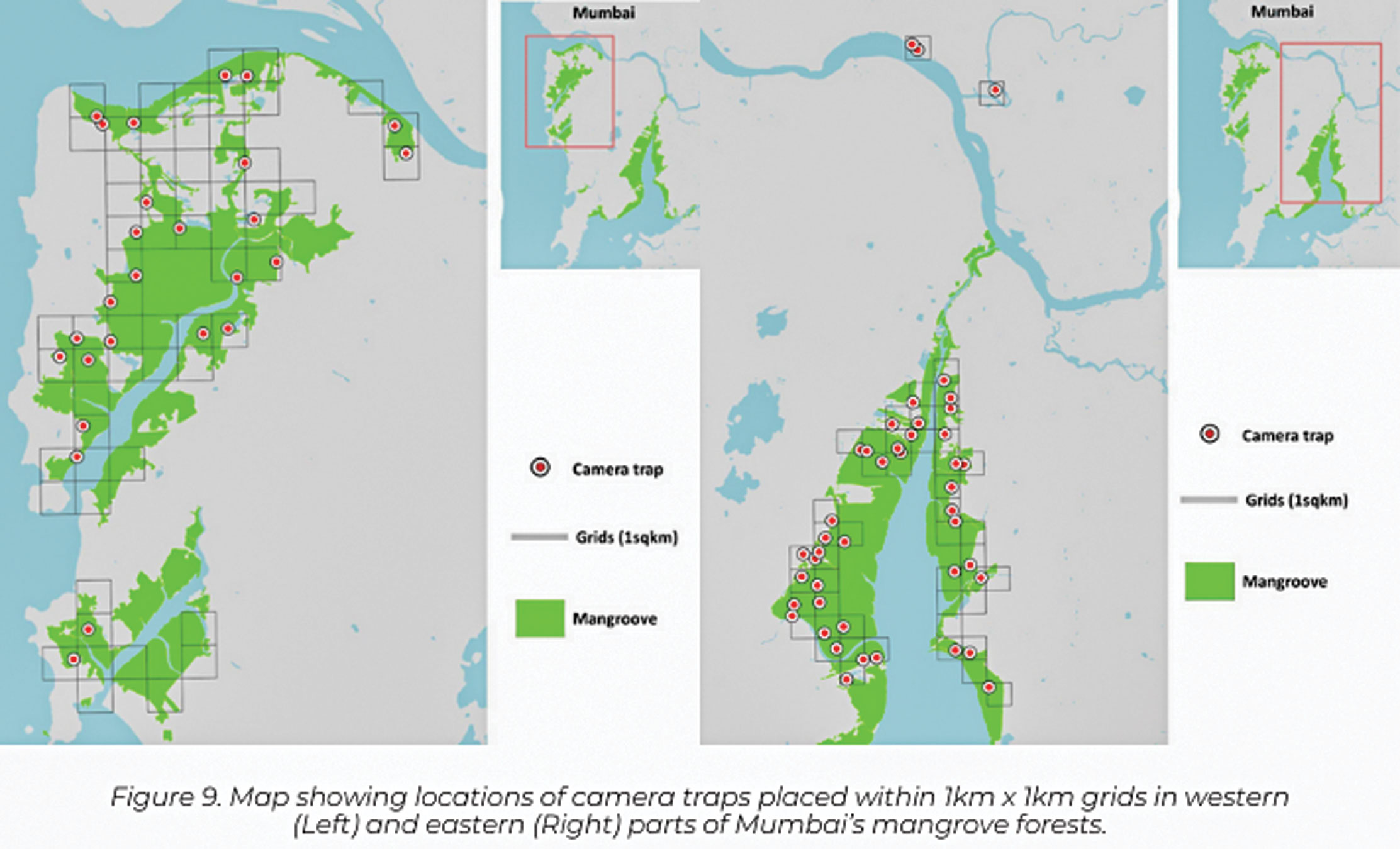

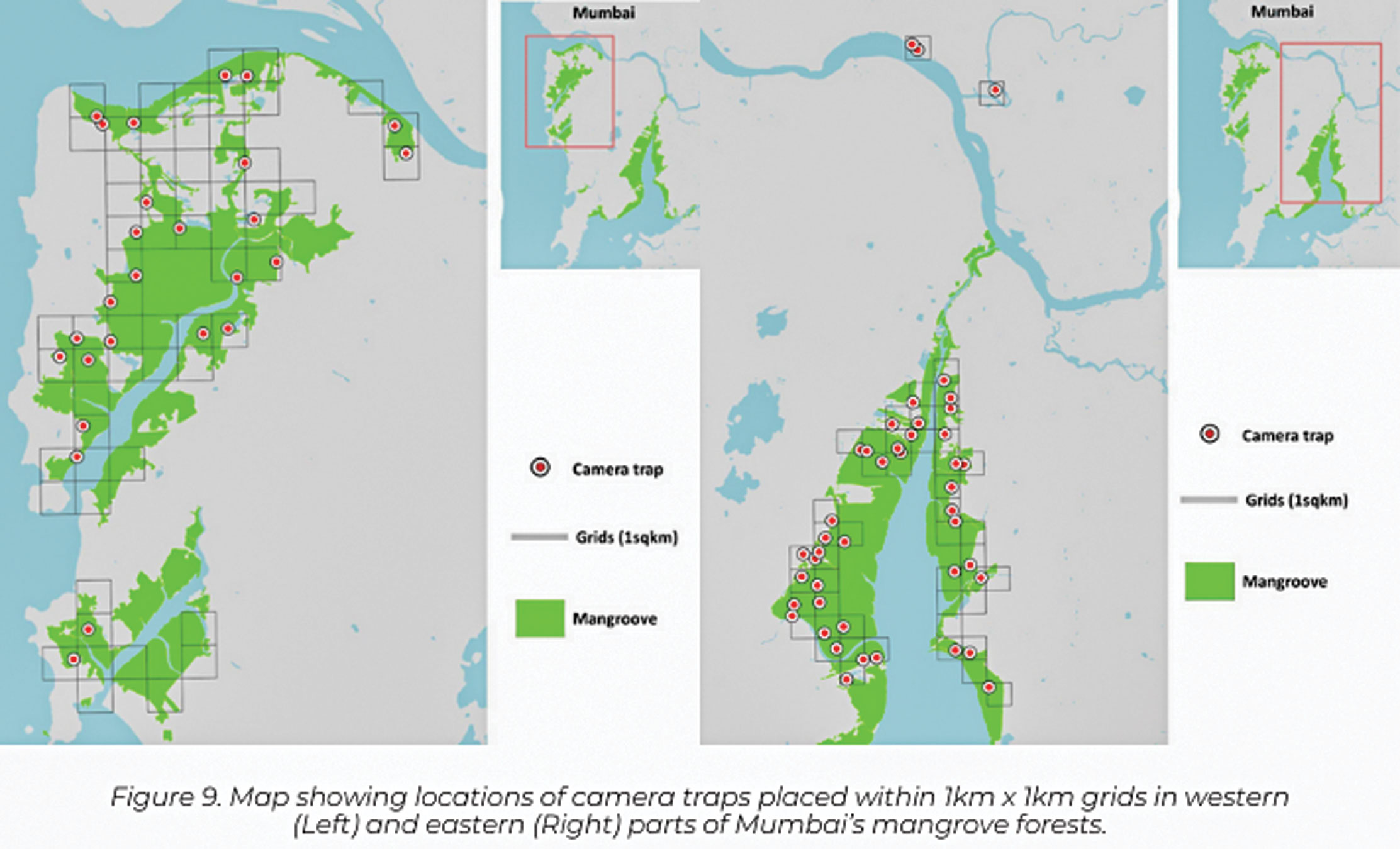

Maps showing locations of camera traps that were deployed within 1 km. × 1 km. grids in the western (left) and eastern (right) regions of Mumbai’s mangrove forests to detect the presence of golden jackals and other mammals. Photo: WCS-India.

From Folklore To Field Notes

It’s no surprise that the golden jackal often finds a place in children’s tales and folklore – clever, resilient, always a survivor. Stories such as Sher aur Siyaar cast them as wily underdogs, outsmarting even the mighty lion. But more often than not, golden jackals have been pushed to the margins of popular imagination. In Disney’s adaptation of The Jungle Book, Tabaqui, the cunning jackal from Kipling’s original, is all but erased – a ghost of the trickster he once was.

For me, though, the jackal was never a shadow. Its eerie, musical howls were the soundtrack of childhood nights in Thane, echoing through the scrub and mangroves around my uncle’s home. I remember lying in bed, wide-eyed, wondering what secret messages passed between them. Even then, I dismissed the old superstition that jackal calls foretold death or misfortune. To me, they made the night feel alive – adding something ancient and wild to the concrete sprawl.

Though golden jackals are famously adaptable – thriving in forests, grasslands, farmlands, and city fringes – the mangroves present a different kind of challenge. Salty, unstable, and constantly shifting with the tides, this ecosystem tests even the most flexible of species. Yet, here they are.

Despite their tenacity, golden jackals have rarely been the focus of scientific attention. Their wide distribution and generalist habits have often left them in the shadow of more charismatic carnivores. They were present in the data – but rarely the heart of the story.

Now, perhaps, it’s time they finally are.

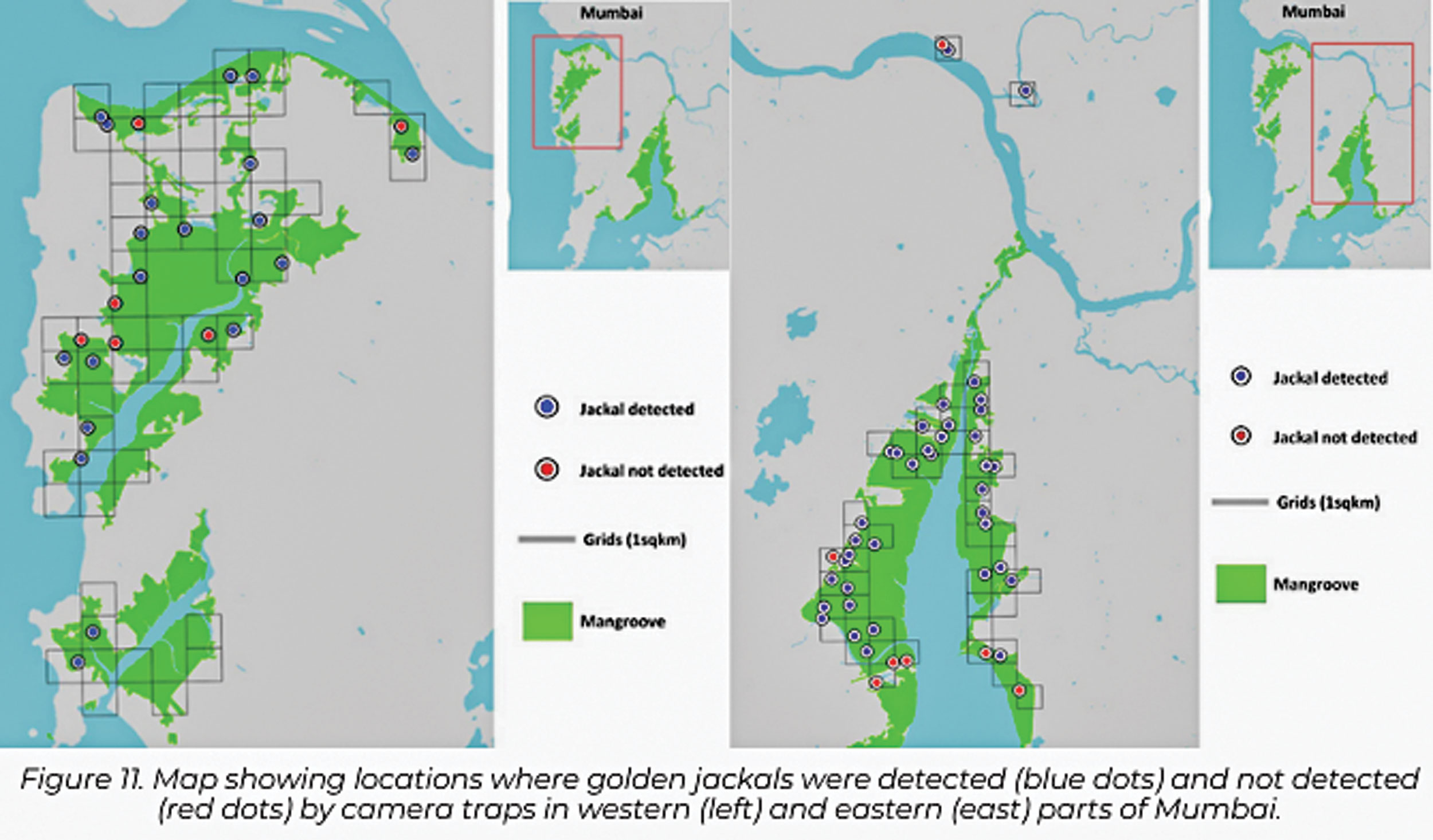

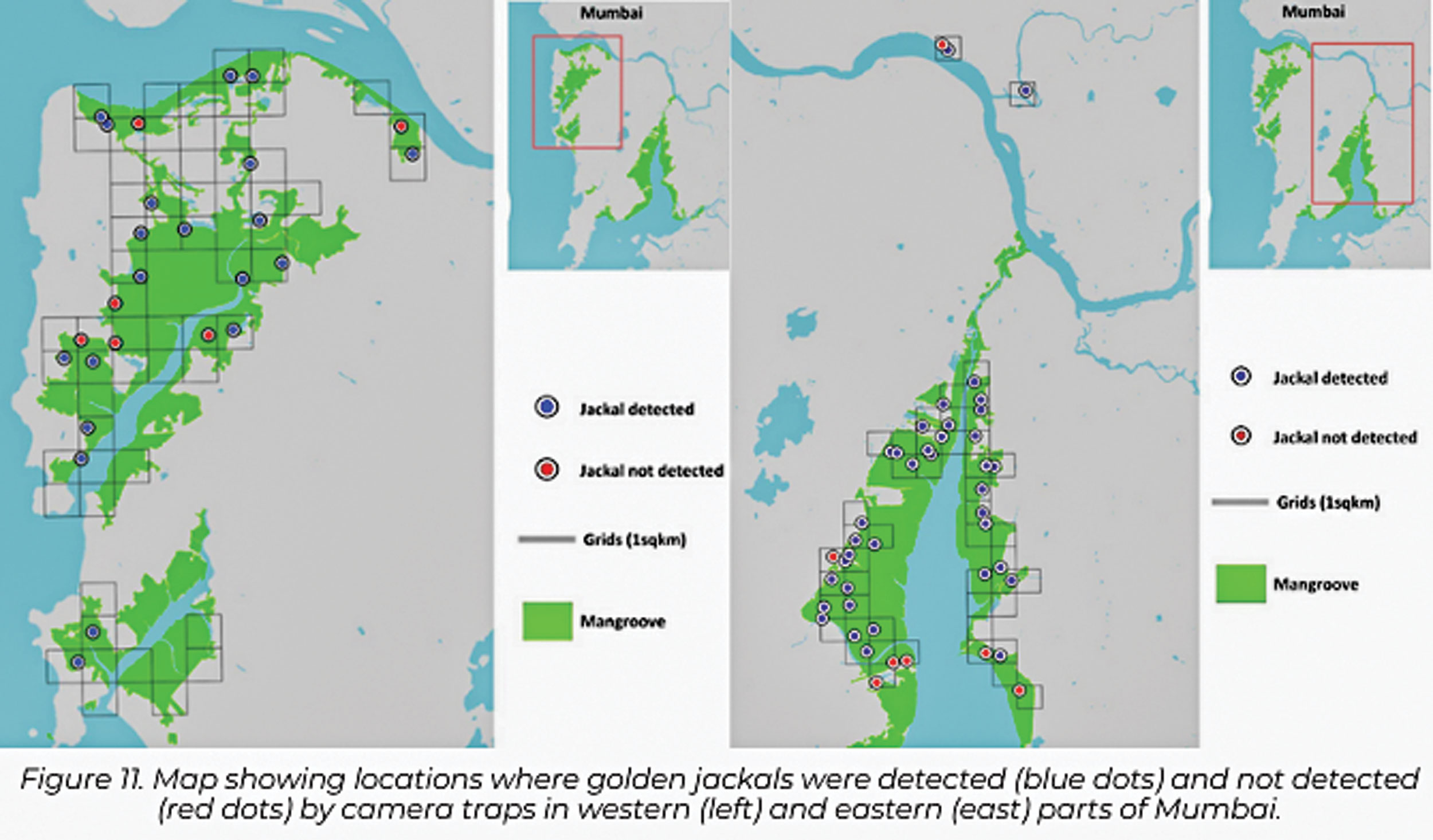

Maps showing locations where golden jackals were detected (blue dots) and were not detected (red dots) by camera traps in the western (left) and eastern (right) regions of Mumbai’s mangrove forests. Photo: WCS-India.

Tracking Jackals In The Mangroves

My journey as an ecologist eventually led me to study leopards – but the golden jackal never really left my mind. So when the Mangrove Cell offered me a chance to study the mammals of Mumbai’s mangrove forests in 2023, I didn’t hesitate. I saw an opportunity not just to return to a long-standing fascination, but to explore a landscape few associate with wild canids.

Our team was a blend of researchers, field technicians, and forest staff, united by curiosity and a shared commitment to the project. Over a year, we surveyed the ranges of the Mumbai Mangrove Conservation Unit (MMCU) across the vast Mumbai Metropolitan Region (MMR). Our work stretched from the western coastlines of Uttan, Gorai, and Manori, across the eastern reaches of Navi Mumbai near Vashi, and into the heart of the Thane Creek Flamingo Sanctuary, where dense mangroves spread like a green web around the tidal waters.

Our goals were simple yet ambitious: map the distribution of golden jackals across this fragmented mangrove landscape, and collect the first baseline data on their population and behaviour. Until then, their presence had only been whispered in anecdotes – rumours and scattered sightings… but no real data. We wanted to find out not just whether the jackals were there, but how they managed to survive.

From the outset, the discoveries surprised me. I had always associated golden jackals with forests, scrub, and grasslands – places such as the Sanjay Gandhi National Park (SGNP), on the edge of the city. Historical records and old management plans mentioned golden jackals there, often alongside hyenas. But in all the years I’d worked in SGNP, since 2011, I’d seen just one – a brief, flickering glimpse near Vasai Creek. By contrast, the mangroves told a different story. Not only were golden jackals present, they seemed to be flourishing! Their ability to adapt to such a harsh, brackish environment – a world ruled by tides – was remarkable.

Fieldwork here, however, was anything but easy. Mangroves are restless, shape-shifting ecosystems. There are no trails, only bunds – narrow earthen embankments built to regulate water. The ground sinks and shifts beneath your boots, and each tide erases the signs of the animals that passed hours earlier.

To observe the golden jackals without disturbing them, we relied on camera traps triggered by motion-activated sensors. But placing these in a fluid landscape posed constant challenges. A mis-timed tide meant wading back knee-deep in thick mud that sucked us in. Our boots would clog with wet sludge, turning short treks into grueling slogs. Every step demanded effort, patience and humility.

But despite the discomfort, the mangroves never stopped giving. There was wonder in the quiet. In the flash of movement between breathing roots. In the calls carried on the breeze. And most of all, in the presence of golden jackals – wild, elusive, and perfectly attuned to a world that so few people ever really see.

Photo: Dr. Yadvendradev Jhala.

Understanding Golden Jackals, with Dr. Y.V. Jhala

Photo: Dr. Yadvendradev Jhala.

Understanding Golden Jackals, with Dr. Y.V. Jhala

The population of golden jackals in India is likely to be between one and three lakh. While this may seem like a large number, considering India’s human population of 1.6 billion and dog population of 60 million, golden jackals are not particularly abundant. Historically, they thrived in agro-pastoral systems, feeding on insects, rodents, and livestock carcasses in village dump yards. However, these systems are disappearing.

Golden jackal populations in India are on a declining trend. Areas that had jackals a decade ago are now often devoid of these wild canids. The major reasons include

. Intensive agriculture: Loss of hedgerows and natural vegetation owing to fencing and pesticide use.

. Loss of denning and feeding sites: Modern farming leaves little space for jackals to raise their young.

. Infrastructure development: Roads lead to high mortality from vehicle collisions. Jackals can’t reproduce fast enough to sustain their numbers in such areas.

Globally, however, jackals are expanding, especially in Europe, where they have colonised parts of Eastern and Northern Europe owing to climate change, reduced persecution, and a decline of wolf populations, which are natural predators and competitors. This is also because golden jackals are highly generalist species, and can adapt to many environments. They tolerate a wide range of temperatures and habitats, from arid zones to tropical rainforests. They have a diverse diet that includes small mammals, insects, garbage, and more. This flexibility allows them to survive in rural, semi-urban, and even coastal environments.

And so, jackals are found in mangrove habitats because of their adaptability and generalist nature. However, population estimates in mangroves are not available, as jackals are not considered at risk and thus are not a monitoring priority. They are present in the Sundarban, where they live on various islands. They are also found in the mangroves of Pirotan island near Jamnagar, Gujarat. Golden jackals are strong swimmers, capable of colonising islands, such as one in the Aegean Sea (Greece), over two kilometres from the mainland.

Dr. Jhala is an eminent wildlife scientist. He retired as the Dean of the Wildlife Institute of India, and was also a prominent member of the National Tiger Conservation Authority.The Hidden Lives Of Mumbai’s Jackals

Over the course of our project, we installed camera traps at 68 different locations across the mangroves, amounting to a staggering 938 trap nights. Despite the relentless tides occasionally submerging a few of our cameras, the treasure trove of images and videos we gathered more than made up for the setbacks. As weeks turned into months, our team huddled together, scrolling through thousands of frames, scanning for glimpses of the elusive creatures we’d come to study – golden jackals, grey mongoose, and jungle cats. But amidst these fascinating shots, something else caught our attention: there was an unsettling number of images showing

free-ranging dogs and humans moving through the mangroves.

Using the data from these camera traps, we were able to estimate the relative abundance of the golden jackals in the area. What we discovered was eye-opening. Golden jackals emerged as the most abundant mammal species in the ecosystem, acting as the apex predators of the mangrove landscape. Of the 2,950 independent capture events recorded, 790 featured golden jackals – far outpacing other wild mammals such as the grey mongoose (92 captures) and the jungle cat (28 captures). On the other hand, human activity appeared in 1,666 images, overwhelmingly dominating the landscape. Free-ranging dogs also appeared frequently, with 374 captures.

An illustration depicting a scene described in an interview with locals, where a free-ranging dog chases a golden jackal, forcing it to escape through the creek water. Free-ranging dogs pose a significant threat to jackals. Photo: Aditi Rajan/WCS-India.

What was even more striking was their behaviour. Golden jackals, like many wild carnivores, were largely nocturnal. Their movements peaked at dawn and dusk – times when human activity was at its lowest. It was clear that the golden jackals had developed a sophisticated strategy to avoid humans, a pattern observed in many other species trying to navigate human-dominated spaces. But there was another, more troubling discovery. While golden jackals skillfully avoided direct contact with people, they frequently overlapped in both time and space with free-ranging dogs. Our camera traps captured footage showing the two species marking the same territories, or urinating at identical spots – small but significant signs of competition and interaction between the two.

Initially, we were fascinated by the resilience and adaptability of the golden jackals. But the deeper we dug, the more troubling the picture became. The overlap with free-ranging dogs raised serious concerns. It heightened the risk of hybridisation – something that’s been documented in other parts of the world. While hybridisation can sometimes offer evolutionary benefits, such as immunity to diseases or parasites from human food sources, it can also have detrimental effects on the health of wild populations. This includes the loss of genetic diversity and the potential spread of diseases between species. In fact, just a year ago, in Navi Mumbai, we witnessed direct interactions between domestic dogs and golden jackals. Tragically, there was a recent and confirmed outbreak of rabies among the golden jackals, claiming the lives of five individuals within weeks.

A camera trap image of a golden jackal pup emerging directly from the muddy mangrove waters. One of the most uplifting findings of our study was confirming a breeding population of golden jackals in the mangroves. Photo: WCS-India/Mangrove Cell.

But the dangers don’t end with disease. The mangroves themselves are under constant threat. Habitat destruction and the growing accumulation of waste within these delicate ecosystems might have devastating effects on the jackals’ survival. These once-productive areas are more threatened now, further endangering the already vulnerable species that call them home.

The Golden Jackal

The Indian subcontinent’s most widespread wild canid, golden jackals are believed to be modern-day descendants of the extinct Arno river dog – a canine species endemic to Mediterranean Europe during the Early Pleistocene, around 1.9 million years ago.

Unlike most of their canid cousins who are adept hunters, golden jackals are primarily scavengers, feeding on carrion and garbage. They occasionally hunt, sometimes even preying on poultry and other domestic animals, and also consume fruits and vegetables. This varied diet makes them versatile carnivores, helping them adapt to diverse environments and spread widely. Along with their ability to survive in a variety of habitats, this characteristic makes them ‘generalists’.

Despite being smaller than the Indian grey wolf, jackals – owing to their wolf-like appearance and widespread misinformation – have been beaten to death in areas with human-wolf conflict, including a recent case in Bahraich, Uttar Pradesh, where wolves killed and injured several people. Additionally, superstitions about wolf derivatives bringing good luck, along with their use in traditional medicine, have made them targets of the illegal wildlife trade.

Apex Predators In A Changing World

While Mumbai’s mangrove forests are gaining recognition for their ecological importance, few are aware that these tidal woodlands are home to the golden jackals – apex predators who have remarkably adapted to this unique ecosystem. Yet, despite their resilience, their world is becoming increasingly fragile.

Our research team deployed camera traps across the mangroves, capturing thousands of images, and complemented this with conversations with local communities. These interactions revealed fascinating insights into the cultural significance of the jackals. One story, shared by local fishermen, struck me as particularly interesting: the belief that jackals dip their tails in the water to hunt crabs. I had heard a similar tale during a visit to Pirotan island in Gujarat, and while we found no evidence to support the story, it certainly added a layer of charm to the mysteries surrounding these wild animals.

The communities we spoke with were largely Indigenous fisherfolk, who lived in close proximity to the mangroves. Their stories reflected how deeply wildlife is woven into the cultural fabric of daily life. One elder shared a striking belief: “When jackals howl, it’s seen as a good omen. In Marathi, we call it Kolha huki or buki.” For these people, the eerie calls of jackals echoing through the mangrove forests weren’t a cause for fear, but a sign of hope.

Camera trap images of golden jackal pups and pups with their pack, playing and exploring just outside their dens. Photo: WCS-India/Mangrove Cell.

Camera trap images of golden jackal pups and pups with their pack, playing and exploring just outside their dens. Photo: WCS-India/Mangrove Cell.

Another local resident offered a belief that seemed to serve as an informal conservation blessing: “If you catch sight of a jackal – especially its face – it means good luck for your business. It’s rare to see them, so it’s considered a sign of prosperity.” These beliefs painted a picture of golden jackals not just as wild creatures, but as symbols of fortune, entwined in the rhythms of life for those who share their habitat.

Despite the many challenges faced by these animals, one of the most uplifting findings of our study was the confirmation of a breeding population of golden jackals within the mangroves. Across the entire study landscape of MMR, we observed packs that included lactating females and young pups, clear evidence of a thriving and established community. One of the most memorable moments was when we captured footage of a pack of seven golden jackals, including pups.

There’s something universally joyful about seeing the young of any species, but witnessing golden jackal pups in such an urbanised environment felt particularly special. Even in smaller packs, we consistently found signs of pups and lactating females – strong indicators that the golden jackal population here was not just surviving, but reproducing, reinforcing the health of the local ecosystem.

Mangroves Of Mumbai

Mumbai, a chain of seven interconnected islets, is protected by a natural cushion of mangroves. More than 20 of the 35 mangrove species recorded in India are found along the city’s coast. Mumbai has the distinction of having the highest mangrove cover of any major metropolis in India.

They play a crucial role in protecting the shoreline and people from storm surges, coastal erosion, and tidal flooding. In a time of climate change-induced sea level rise and erratic weather, the mangroves have become ever more important as protection, and by being carbon sinks, for mitigation. They also provide other ecosystem services such as water quality maintenance and flood protection.

These evergreen forests are found in estuarine regions that have wide and gently sloping mud-flats. They also exist in the intertidal region of shallow bays and creeks. As complete ecosystems, they support a rich web of species of flora and fauna – over 300 flora species, more than 200 marine fauna species, over 122 bird species, as well as mammals, butterflies, and unique herpetofauna. Mangroves serve as nurseries to various species of fish, such as black pomfret and golden anchovy, which are economically important. Healthy mangrove forests remain at places such as Vasai, Thane Creek in Airoli, Sewri, Malad, Mahim-Bandra, Vikhroli and Versova, among a few other spots.

Despite their ecological and commercial value, mangrove habitats are vanishing owing to urbanisation, illegal encroachments, and industrial pollution. To safeguard Mumbai’s mangroves and their residents, it’s imperative to enforce existing environmental laws, promote community awareness, and integrate mangrove conservation into urban planning initiatives.

A team member and Forest Department staff inspect a camera trap deployed in Mumbai’s mangroves. Placing these in a fluid landscape posed constant challenges. A mis-timed tide meant wading back knee-deep in thick mud that sucked us in. Every step demanded effort, patience and humility. Photo: WCS-India.

Coexistence Is Possible – If We Choose It

Golden jackals may not be considered a charismatic species but it is one worth understanding. While common in many parts of the world, they remain elusive and enigmatic. In Mumbai, however, they’ve adapted remarkably to the rapidly changing urban landscape, offering a glimmer of hope and underscoring the urgent need for long-term, in-depth studies to better understand and protect both the golden jackals and their mangrove habitat. Future research should focus on their movement ecology, interactions with humans, hybridisation, and disease transmission dynamics amid ongoing urban development.

Our findings underscore the golden jackals’ incredible adaptability and highlight the critical importance of preserving the remaining urban wilderness. As Mumbai continues to expand, both vertically and horizontally, the story of the golden jackal reminds us that urban spaces and wildlife need not be mutually exclusive.

The continued survival of these apex predators in Mumbai’s mangroves is a testament to nature’s resilience. It also serves as a call to action. To protect these amazing animals, we must implement urgent and informed conservation strategies that blend scientific research, habitat protection, and public engagement. By choosing to safeguard such creatures, we are not just preserving a species; we are shaping the future of cities that harmonise with the wild heart still beating within them.

The Signs are Getting Harder to Ignore

Lately, I have been seeing a noticeable increase in golden jackal rescues, particularly cases showing symptoms of rabies. What’s concerning is that many of these cases are presenting symptoms of rabies and when tested post mortem, several have come back positive. These are ones where the furious form of rabies has been noticed; worryingly, we may not even get to know of animals presenting the dumb form. The Forest Department and local organisations have been actively responding to these reports, and capturing and removing the affected individuals from the landscape.

This rise is likely linked to the fact that jackals are increasingly interacting with free-ranging dogs, especially around feeding sites where they often scavenge side by side. The close proximity means there’s a much higher chance of disease transmission, and unfortunately, wildlife such as jackals have very little, if any, immunity to viruses like rabies. And it’s not just rabies. While cases are being reported from Mumbai, even in Pune’s surrounding areas we’re seeing jackals, hyenas, civets, and other canids showing up with signs of canine distemper virus (CDV) as well. Again, the common factor is the shared space between free-ranging dogs and wild carnivores in human-dominated landscapes, where the overlap makes these disease spillovers almost inevitable.

Neha Panchamia, Founder, ResQ Charitable Trust

Nikit Surve As Project Manager for the Urban Biodiversity Programme at the Wildlife Conservation Society – India, he brings over a decade of experience studying human-animal interactions in Mumbai’s urban landscape. His lifelong fascination with the natural world continues to drive his work in understanding and conserving urban biodiversity.