The Sanctuary Papers: June 2021

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 41

No. 6,

June 2021

By Abinaya Kalyanasundaram

Winter Heroes

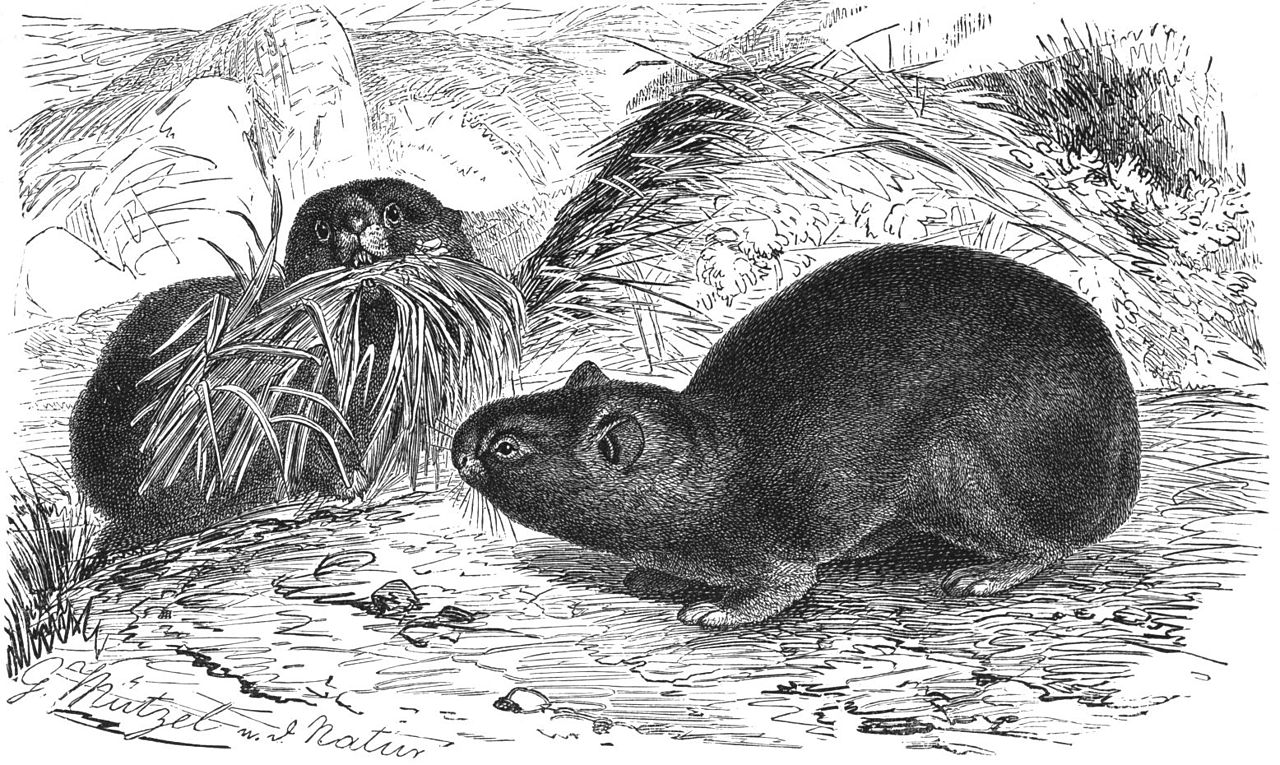

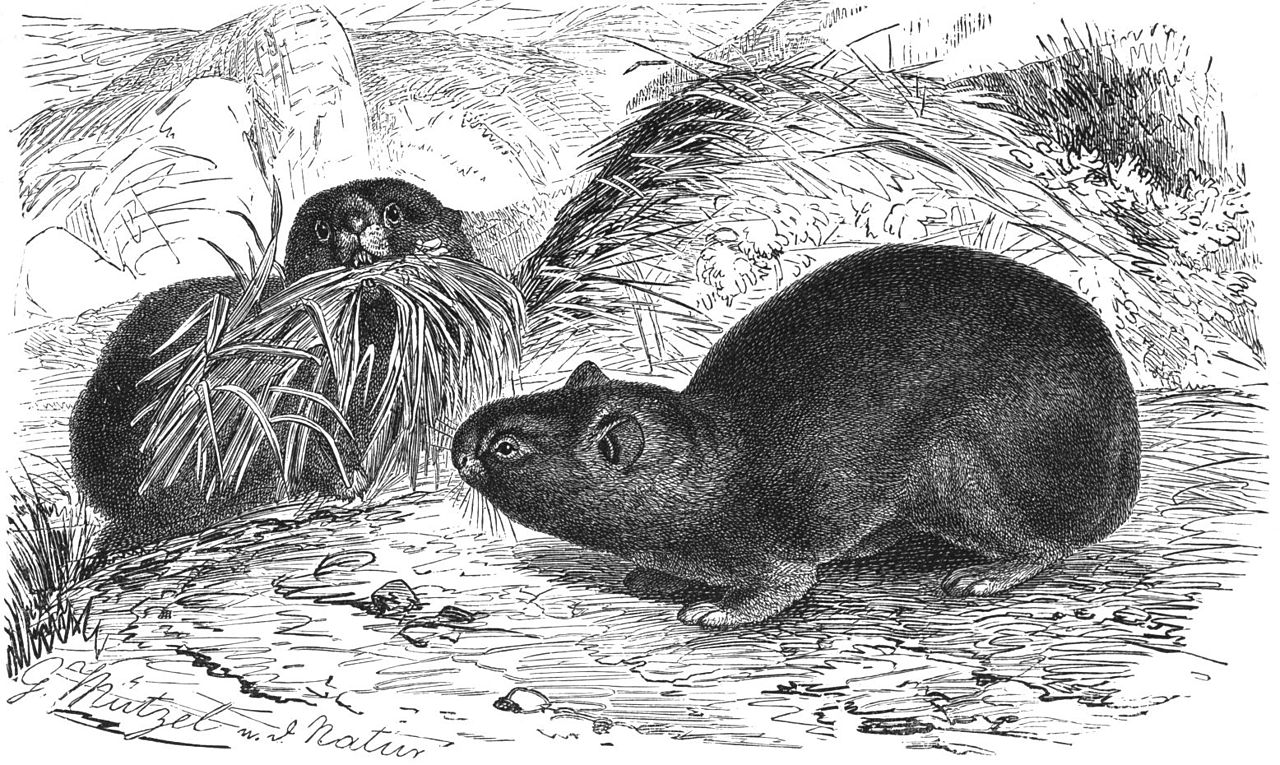

Illustration: Wikiwand/ Public Domain.

In the cold desert of Ladakh lives the pika. Resembling a mouse, but closer to rabbits, this tailless little rodent-like creature does not hibernate in winter. Of the 28 to 32 species worldwide, five are known to exist in India, all in Ladakh. Some use burrows in meadows and others use crevices of the talus (rocky patches). The largest is the Ladakh pika Ochotona ladacensis, weighing over 200 g. Even when deep snow blankets the landscape, the diurnal pika is active, often enjoying soaking in sunlight in late afternoons. Its fur grows thicker as winter approaches. It has also evolved a process called non-shivering thermogenesis to survive the bitter cold and turns its white adipose tissue to brown, to increase body temperature and aid metabolism. How does it find food with all the grass and plants buried under snow? An expert food-gatherer, it collects grasses and plants that will be sun-dried and then stockpiled in summer, ready to be gorged on in winter.

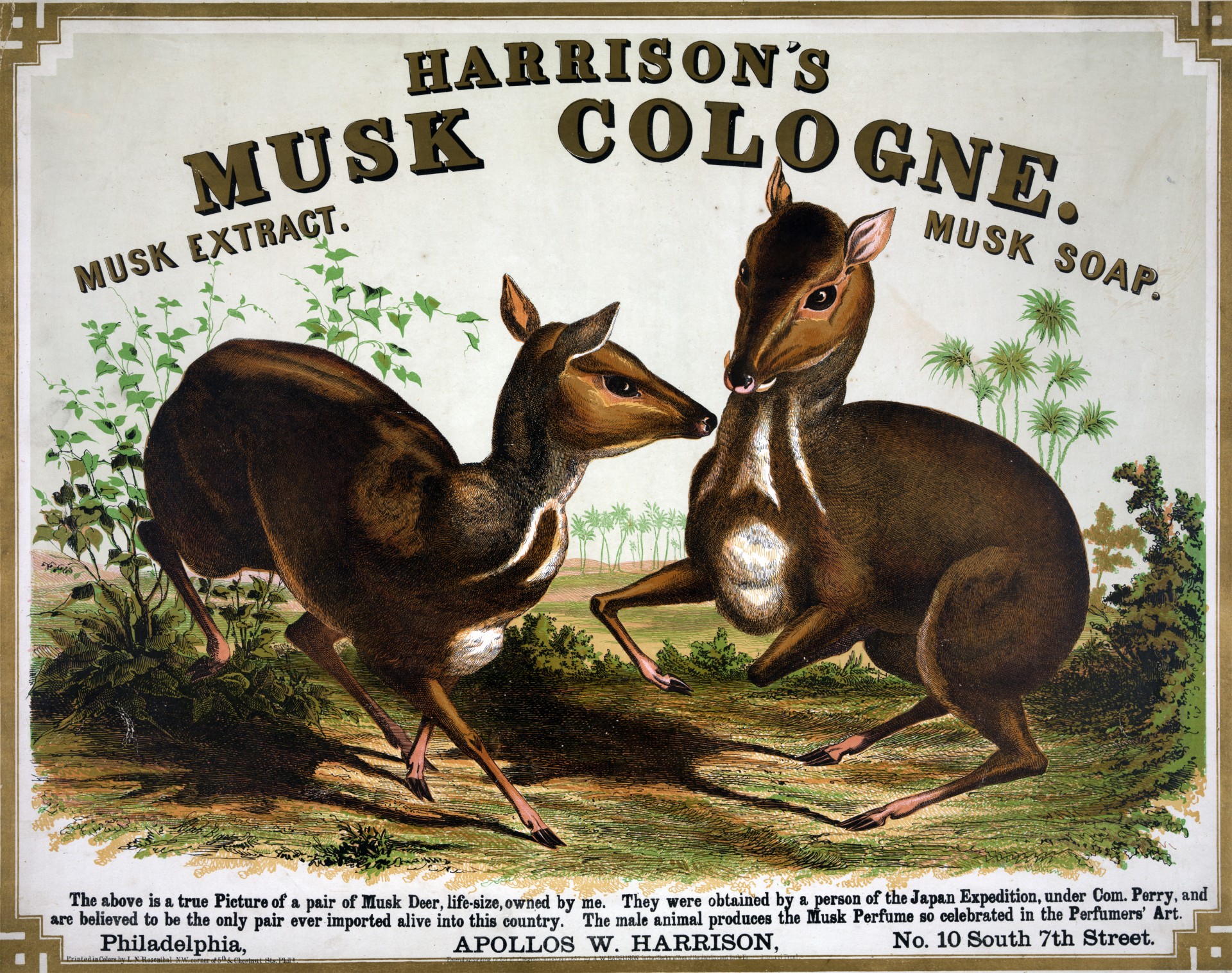

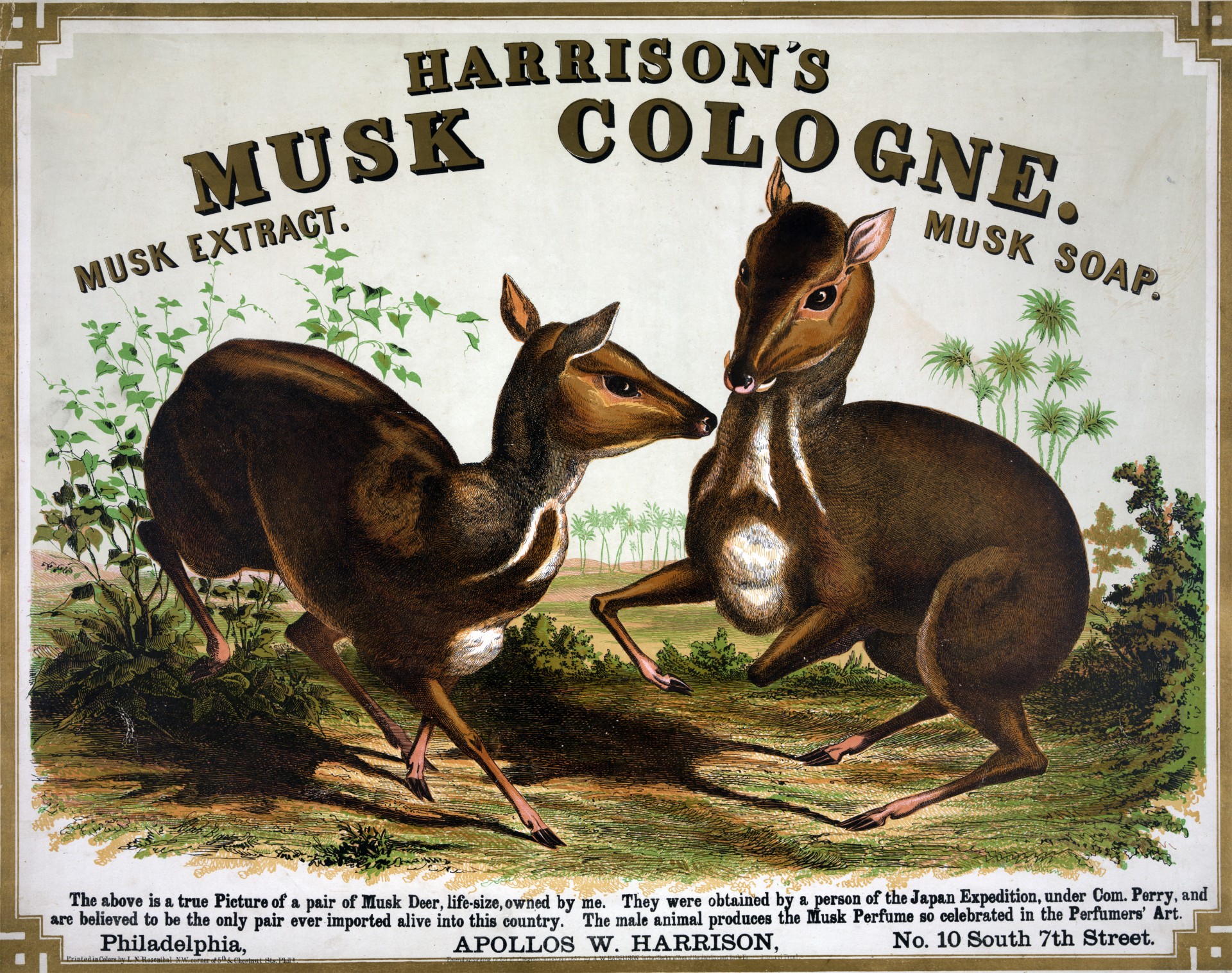

The Legend of Musk

Illustration: Public Domain.

Illustration: Public Domain.

In the mystical world of perfumery, the discovery of one scent back around 3,500 B.C. in China and India grabbed humans by the nose. Musk had a unique, distinctive fragrance, and quickly became every perfumer’s dream. Even today it is the base scent for many perfumes in the world. Universal and versatile though its scent may be, the way it is sourced is not quite pleasant. Sourcing of musk often involves killing the male deer for its caudal glands, obtained by trapping the deer from the wild. The glands are dried and the resultant black granular ‘musk grain’, is infused with alcohol. Musk deer are not true deer (cervids), in that they do not possess antlers, but sport small tusk-like canine teeth. They dwell in the forested and scrub mountain habitats across the Himalaya. Seven species are known to exist including the Kashmir musk deer Moschus cupreus. During the rutting season, males secrete the musk to attract females, and it is this scent that has led them to become victims of human exploitation. Highly prized, musk has been traded using the silk route in ancient times and is still unfortunately used in traditional medicine for its alleged stimulation and sedative properties. Synthetic alternatives exist and musk deer trade has been banned by the Convention on the International Trade in Endangered Species, or CITES, since 1979.

World’s Costliest Stigma

Illustration: Pierre-Joseph Redouté/ Public Domain.

The saffron crocus Crocus sativus may seem like any other beautiful flowering plant, but within its cup-shaped lilac petals, it holds a treasure coveted for its unique essence around the world – saffron. Saffron has long been considered the world’s costliest spice. The perennial herb is used for flavouring and colouring culinary dishes and in medicinal and pharmaceutical industries. India produces about seven per cent of the world’s saffron (Iran takes the top spot with 88 per cent), all of which is grown exclusively in Jammu and Kashmir, majorly Pampore village, 14 km. from Srinagar. Kashmir saffron, in particular, has a high crocin content and rich aroma, making it a premium variety, more than that of Spain and Iran. Just one kilogramme costs about Rs. 2,50,000! The extremely high cost seems justifiable considering the enormously labour-intensive process. Crocus sativus grows in Kashmir’s well-drained karewa soil, at elevations of about 1,500-2,000 masl. It needs extreme heat and dryness in summer and extreme cold during winter, and blooms only in the autumn months of October. The flowers have to be hand-picked and the red stigmas separated one by one, then carefully toasted dry on a charcoal fire. Over 1,50,000 flowers are thus picked and processed to produce just one kilogramme of saffron!

Trout Tales

Illustration: Public Domain.

Two trout species are found in Kashmir – the rainbow trout Salmo irideus (bottom) and brown trout Salmo fario (top). Interestingly, neither are native species, both having been introduced by anglers into the valley’s waterways a century ago by the British, from Northern Europe. It all began when Maharaja Pratap Singh, in 1899, sent a gift of a Kashmir stag to the Duke of Bedford, who courteously sent back 10,000 trout eggs as a token of gratitude. All perished enroute the long ship journey, but a second shipment, of 1,800 brown trout fry from Scotland in 1900 survived and reached Bombay aboard the P & O liner ‘Caledonia’. From here they were transported to a hatchery at Panchgam, where the Dachigam National Park now exists. Over the next few years, trout continued to be introduced in streams across the Kashmir valley and in 1912, rainbow trout joined the fray. Exotic species are a major threat to local flora and fauna and it is anyone’s guess what the impact of this introduced species has on local fish species. Conservationists now ask that, as with the Sheep Farm, the trout hatchery also be shifted out of Dachigam.

Of Territories and Symbols

Illustration: Public Domain.

Every state and union territory of India has its own symbolic tree, animal, bird and flower. The essence of this practice is to spur prideful conservation of the species to ensure its future survival. The Union Territories of Jammu and Kashmir, and Ladakh, however, are now faced with a strange dilemma. Prior to the Jammu and Kashmir State Reorganisation Act, 2019, the erstwhile J&K state animal was the hangul Cervus hanglu hanglu and state bird the Black-necked Crane Grus nigricollis. However, the bifurcations of the state into two Union Territories created a problem. The hangul exists only in J&K’s Dachigam National Park, while the Black-necked Crane is only found in Eastern Ladakh. J&K is now looking for a flagship bird – the Kashmir Flycatcher Ficedula subrubra, a small rare bird that breeds in Kashmir, is a strong contender. Considering that state animals and birds usually receive conservation priority, this could help save the vulnerable bird from extinction. As for Ladakh’s symbol animal, no strong contenders have been identified as of yet, though the snow leopard is likely to be the animal of choice.

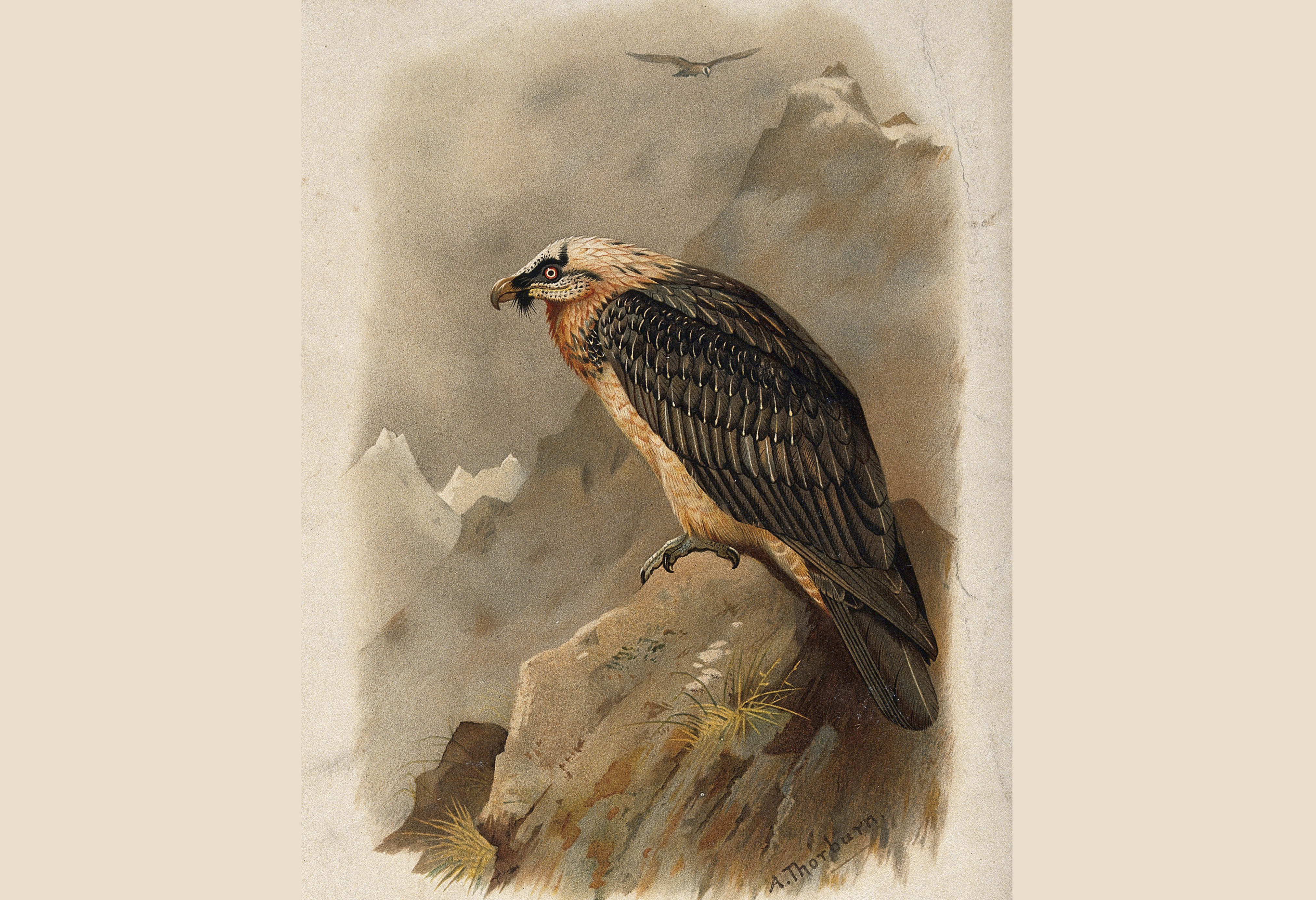

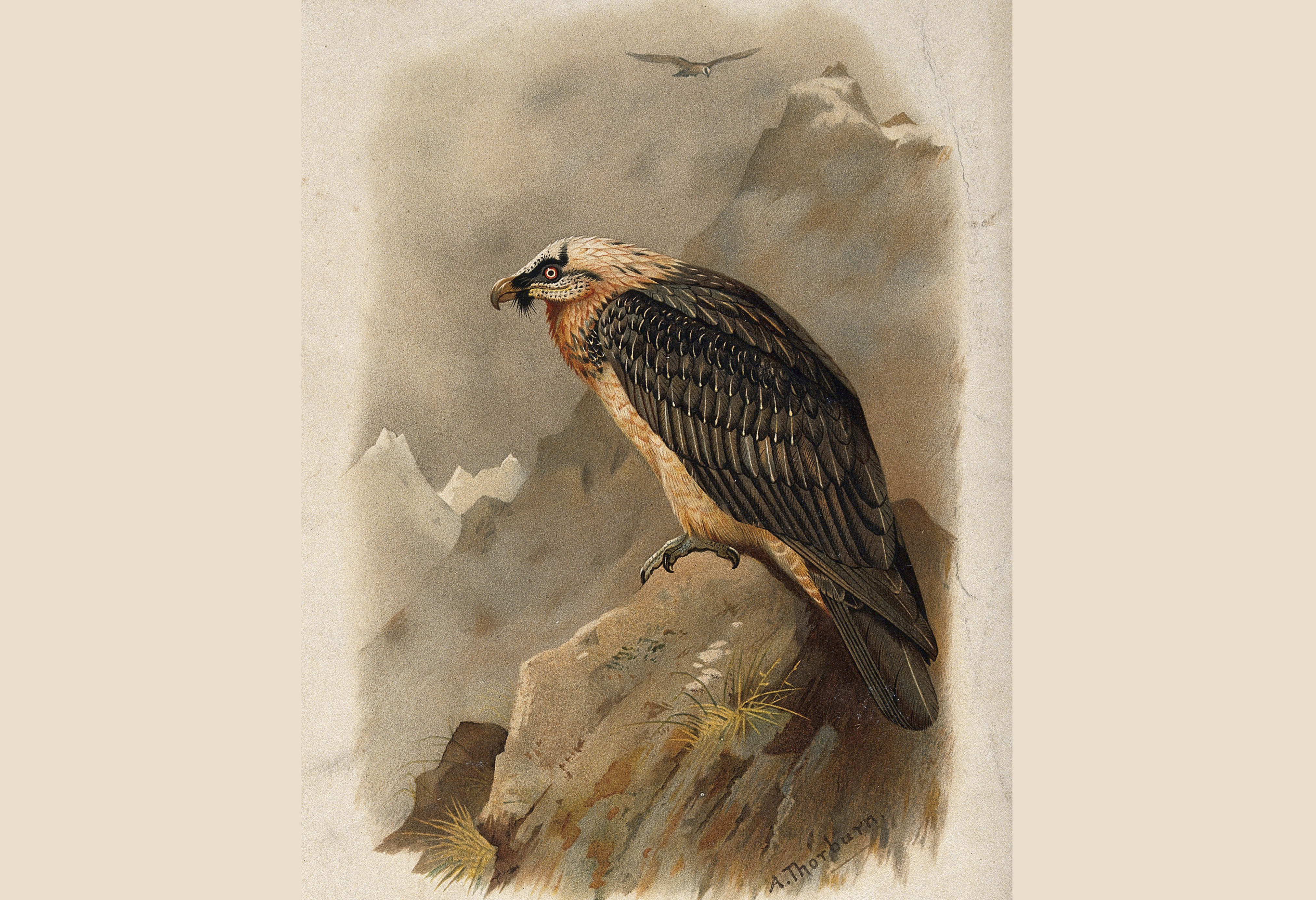

Bare Bones

Illustration: W.Wellcome/ Public Domain.

The Bearded Vulture or Lammergeier Gypaetus barbatus, is a resident avian, present in Himalayan habitats of J&K and Ladakh. It sports reddish-yellow and white feathers on its head and chest, while its wings and tail are an intense greyish black. Relatively small-headed, it has a thick neck and characteristic bristles below the beak giving the impression of a beard. Its most unique trait, however, is its feeding habits. It almost exclusively depends on bones, which can be digested by its strong gastric juices. The marrow that it gets to is also a highly nutritious source of energy. This is the world’s only species known to do so. This has caused the species to evolve differently from other vultures in that it is not ‘bald’ since it does not have blood and gore sticking to its head feathers. The Lammergeier forages over massive ranges, which may extend across 700 sq. km. in a day. It uses thermals to soar effortlessly in flight. When food is found, the bird strips the carcasses of bones, flies to considerable heights and drops the bones, sometimes repeatedly, until they shatter to expose the marrow within. The evolutionary advantage of its diet is the lack of competition for the food upon which it depends!

.png)

Illustration: Public Domain.

Illustration: Public Domain.