The Sanctuary Papers - December 2023

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 43

No. 12,

December 2023

Text By Shatakshi Gawade

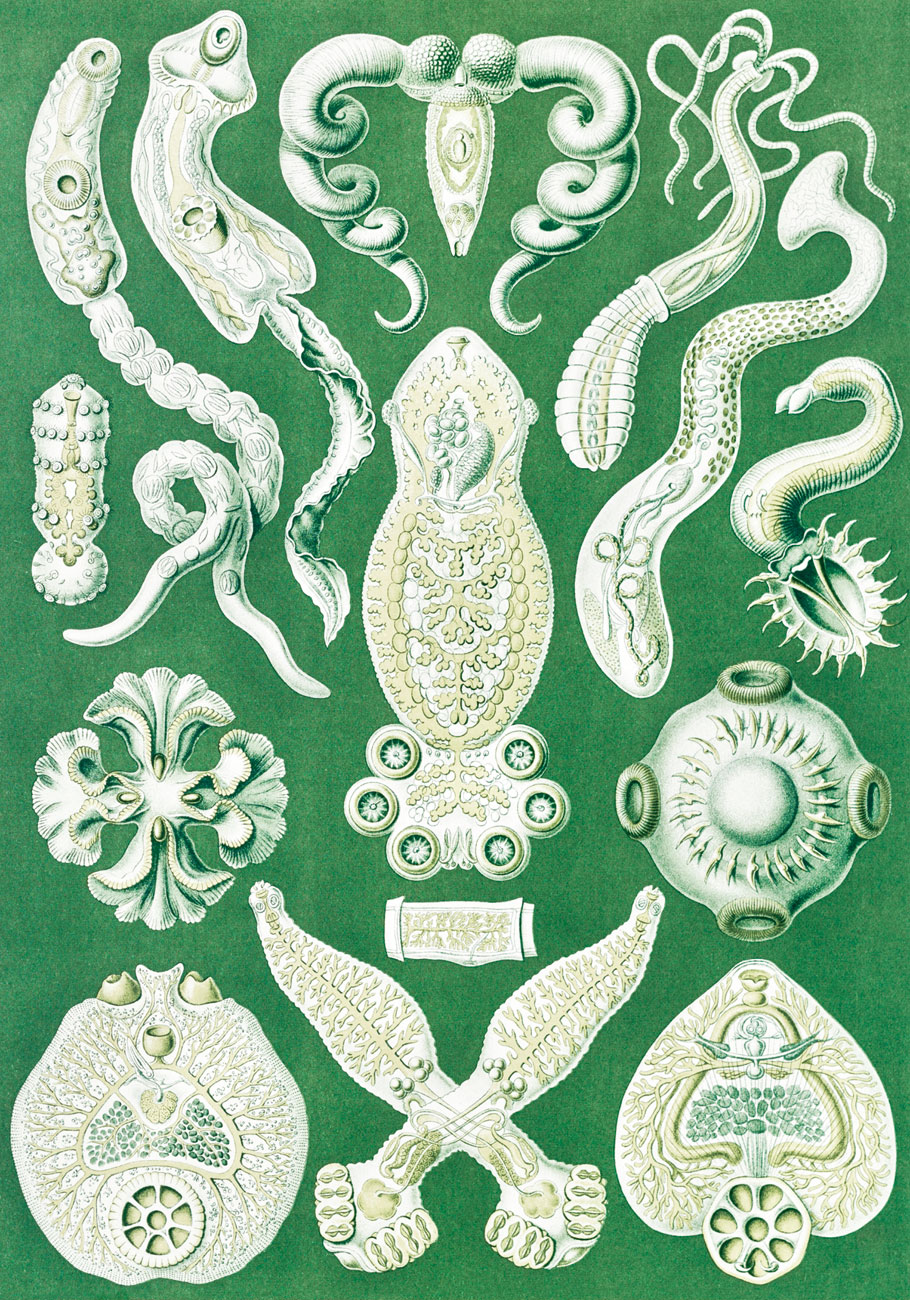

Saving Private Parasite

Photo: Public Domain/Rawpixel.

All species have parasites! The lemur and its parasite have likely evolved together over 60 million years! Parasites are ‘puppet masters’. For instance, to reach their ultimate host the trout, horsehair worms infect crickets and force them to drown. The cricket is an important food source for the trout. By ensuring access to food, the parasite must ensure that the endangered fish survives! Not enough studies have been done on how many parasites there are, and their associations. While we try to eradicate some dangerous ones such as the anopheles mosquito that causes malaria, scientists believe the time has come to embark on a mission to save parasites that might well be holding entire ecosystems together.

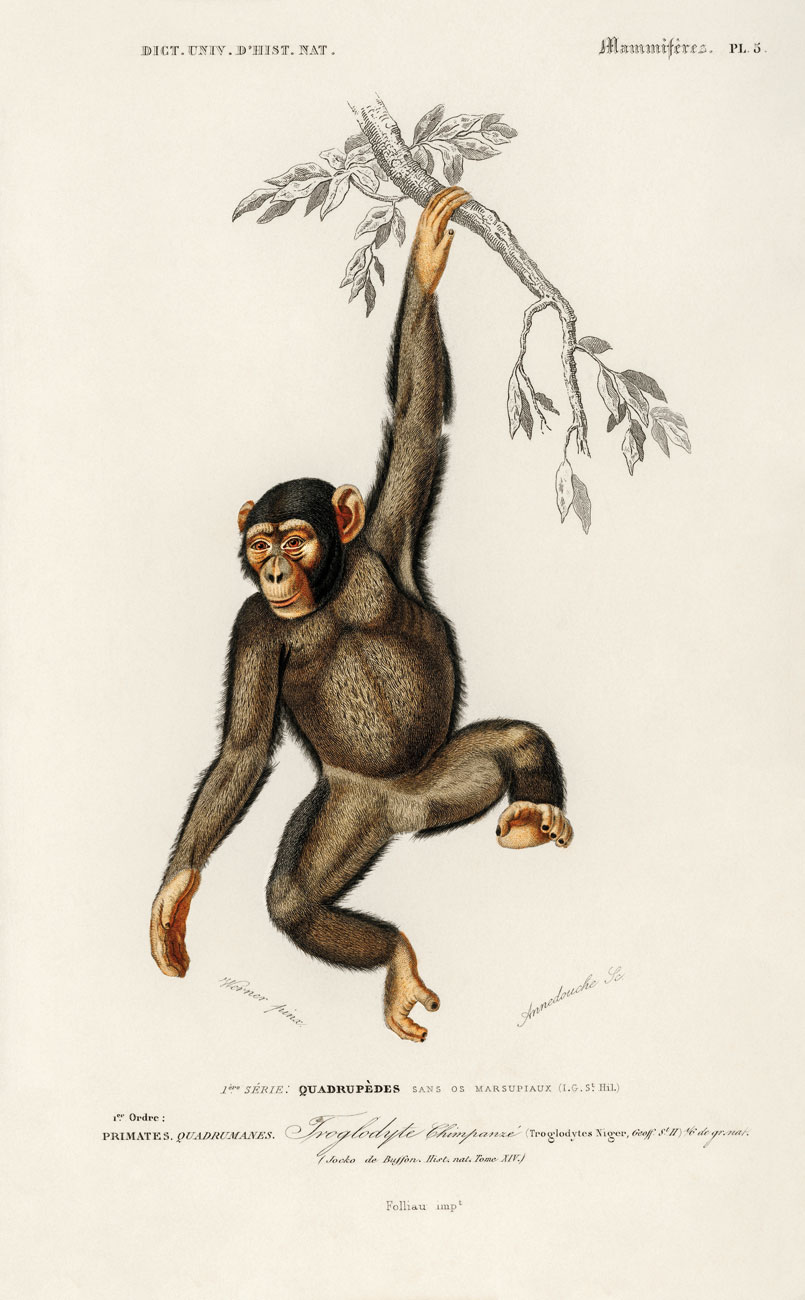

Grandmotherly Lives

Chimpanzees, with whom we share 98.8 per cent of our DNA, are like us in another aspect – females of the species experience menopause, and continue to live their lives as non-reproductive members of the group. This is unlike other species, where they remain fertile almost until their death. From 1995 to 2016, scientists followed 185 chimps Pan troglodytes of the Ngogo community in Kibale National Park, Uganda. On analysing their urine when it showered down from trees, they found a steady decline in the hormones that control ovulation and thickening of the uterine lining (oestrogen and progestin). The number of births among these primates began reducing after 30, ceased completely at 50, and they lived well into their 60s!

The grandmother hypothesis suggests that older females could help take care of their daughter’s baby, though this doesn’t apply to chimps as young females leave the group to mate and are thus separated from their mother. Another theory suggests an attempt at reducing competition for younger members. And finally, it is argued that females run out of high-quality mitochondria (which the male does not furnish), and thus stop ovulating and reproducing.

Photo: Public Domain/Rawpixel.

While this phenomenon of non-ovulation after a particular period is common among lab and zoo species, scientists have yet to determine whether this is the case for all chimps. Five other mammals, which have a long post-reproductive life are cetacean species such as the beluga whale Delphinapterus leucas, short-finned pilot whale Globicephala macrorhynchus, false killer whale Pseudorca crassidens, narwhal Monodon monoceros and orca Orcinus orca.

Smacking Good!

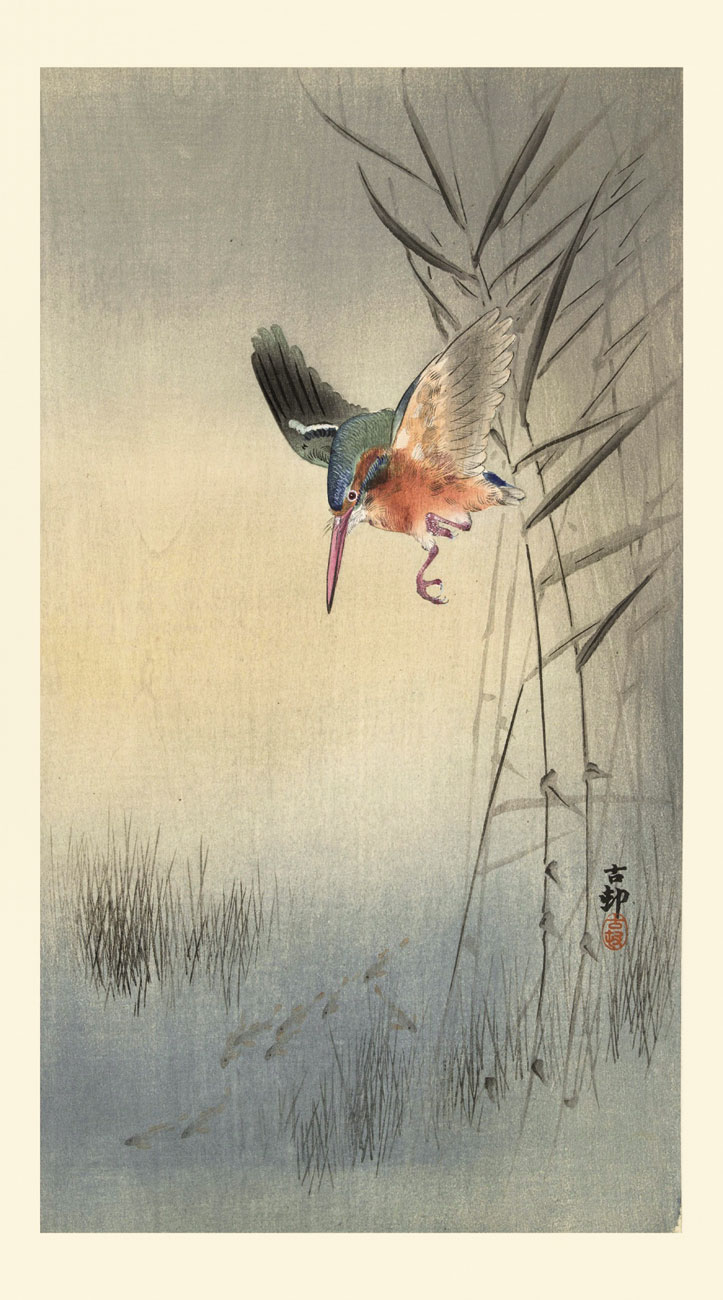

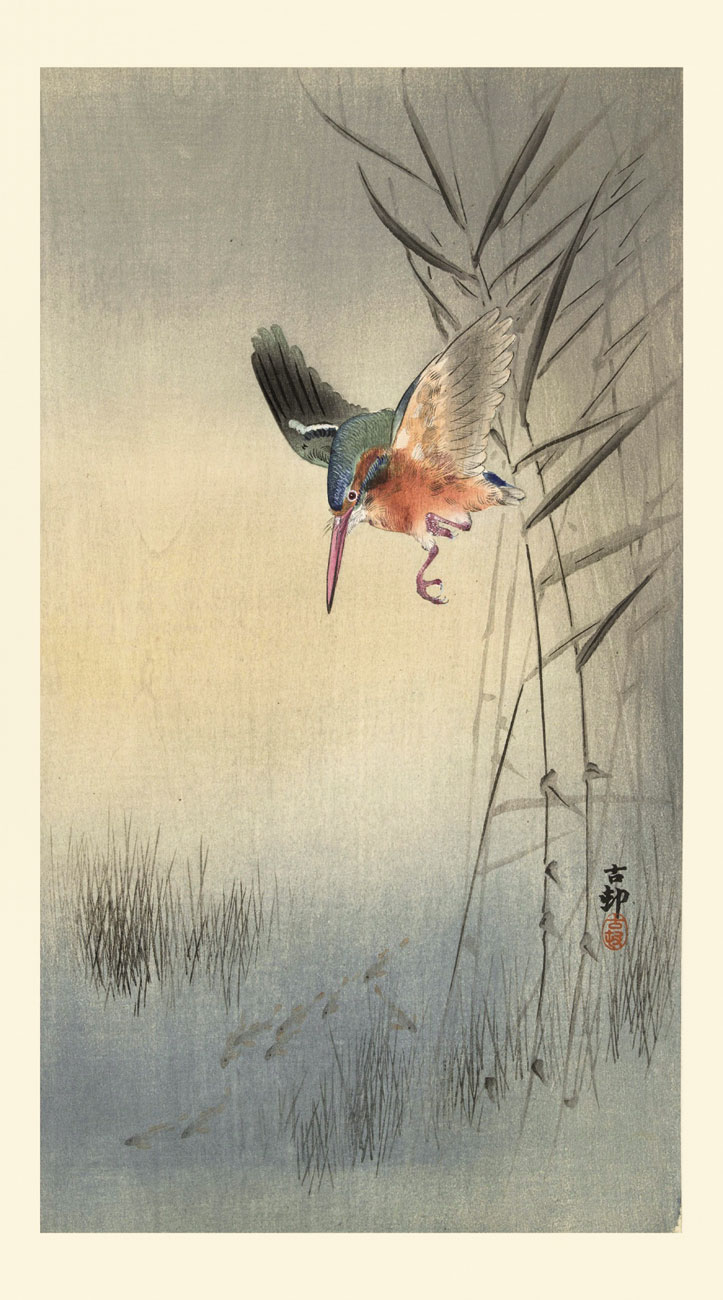

With its wings pinned to its body and feet tucked in, the kingfisher dive bombs into the water, zooming in at 40 kmph. to precisely zero in on its next meal. These dives put tremendous pressure on the bird’s beak, head and brain, and such a head-first jump into the water would give a human a concussion through the sheer force of the impact. The kingfisher, however, comes out unscathed after repeatedly hitting its head against the water’s surface. The key is in its genes – a tweak most likely protects the kingfisher from getting a concussion.

Photo: Public Domain.

Scientists studied museum specimens of 30 species of kingfishers (family Alcedinidae), of which some were diving species while others were not, to understand if there was genetic convergence. They found 93 genes that had changed, of which one was of particular importance. This change causes the gene to produce a protein called ‘tau’, which helps cells stabilise and could help the birds dive. Intriguingly, this same protein is found in humans who have either suffered many concussions or have neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s. In the bird’s case, the protein has been used to mitigate the effects of impacts.

Did You Know?

The mountain chicken frog Leptodactylus fallax population has shrunk to an alarming 21 individuals, from hundreds of thousands in Dominica. The devastating decline was caused by a chytrid fungus; 18 months after it arrived on the island, it destroyed 80 per cent of the frog's population. This is believed to be one of the ‘fastest extinctions’ of a wild animal on record. The frog grows to over a kilogramme, and was a staple in the country’s cuisine.

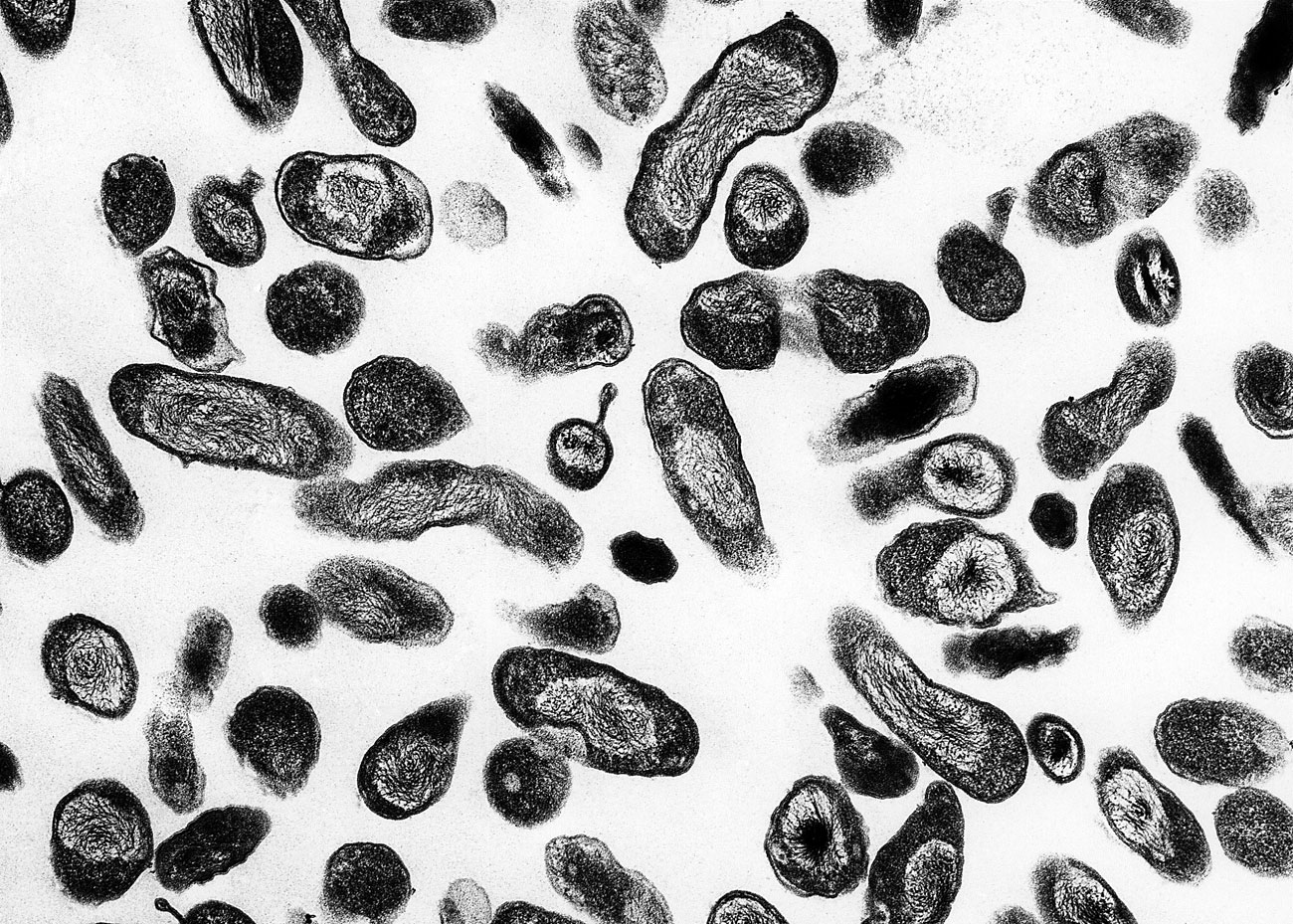

The World Under Our Feet

It’s definitely easy to assume that life above the soil has the most biodiversity. But look closer at what you are walking on, you might just have walked over hundreds of living beings – one teaspoon of soil can have one billion bacteria and over a kilometre of fungi strands! The soil is the most species-rich habitat on the planet, with 59 per cent of the Earth’s species living in this ubiquitous terrestrial habitat.

Photo: Public Domain/Rawpixel.

This finding is a big jump from the previous estimate of 25 per cent of life in the soil. Even with a 15 per cent error range for the estimate, which makes the number of species in soil vary from 44 to 74 per cent, soil is the most biodiverse habitat of all! Importantly, scientists feel that this figure could be higher considering that soil, home to an estimated 50 per cent of bacteria, 85 per cent of plants and 90 per cent of fungi, is extremely understudied. Despite knowing that 95 per cent of our food is grown in it, soil hasn’t featured much in conservation attempts owing to the paucity of information about it. Every year, 24 billion tonnes of fertile soil is lost to intensive farming. Researchers suggest that less intensive farming, habitat conservation and regulation of non-native species will help restore life in soil.

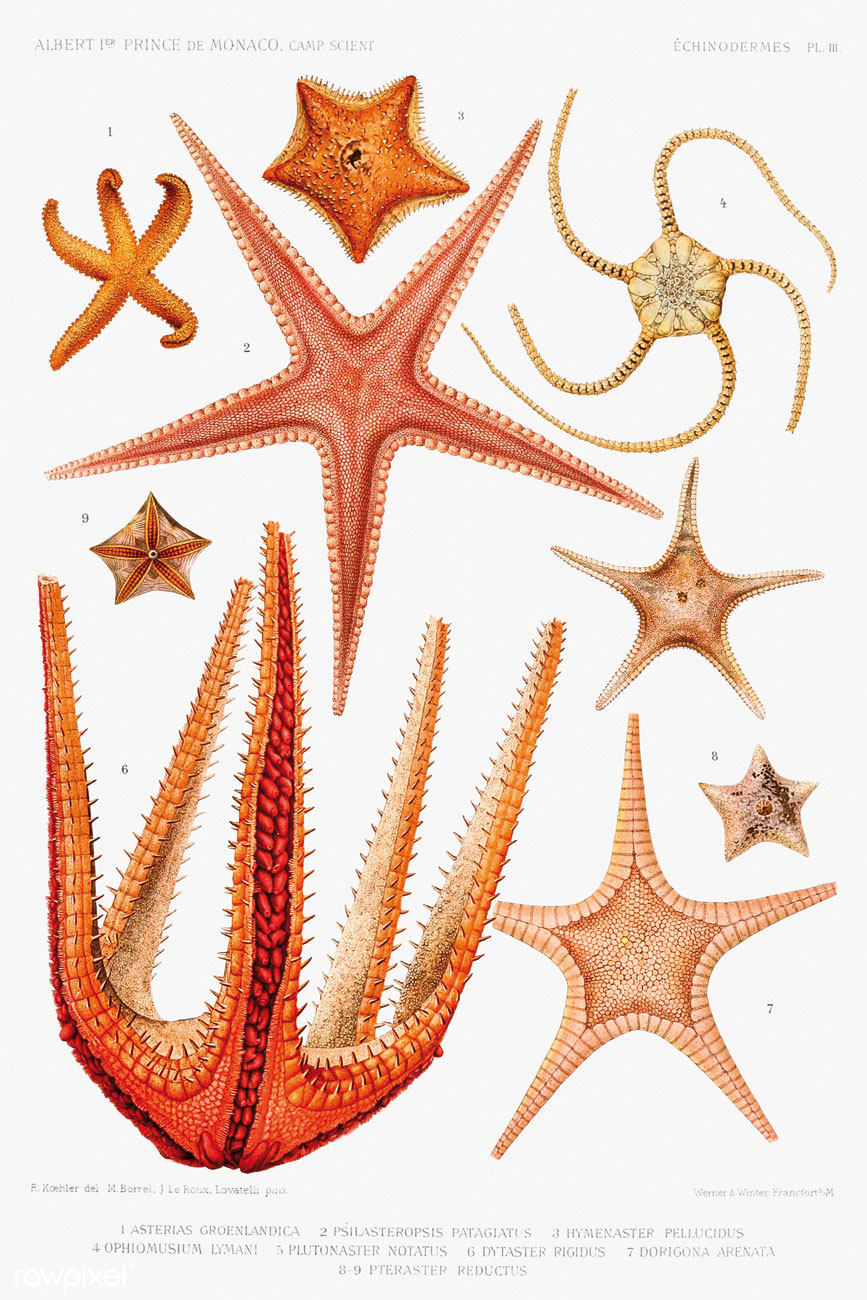

Dramatically Decoupled

The beautiful five-armed stars that occasionally wash onto sandy beaches are quite the enigmas for scientists, who haven’t been able to make head nor tail of its body, literally! Researchers have been wondering about its front and back, and if it has a head at all, until the latest genetic research suggested that the entire starfish is largely a head! The marine creature may have lost its torso, which can be seen in fossils, and tail along the evolutionary way. So essentially, the starfish is a head crawling and floating across the sea floor.

Photo: Public Domain/Rawpixel.

These echinoderms of the family Asteroidea begin life as eggs, from which larvae hatch and float in the water like plankton. These young starfish are still bilateral (where the body is divided symmetrically into two halves), just like their common ancestors. Once they settle on the floor, their body transforms into the star-shaped pentaradial body. This transition to such a different body structure had flummoxed researchers completely, who couldn’t relate the body of the starfish to any of its bilateral ancestors. When a 3D map was created using data revealed by in-depth genetic analysis, scientists found that the genes responsible for creation of the trunk were inactive, along with a 'dramatic decoupling' of the head and the trunk.

Did You Know?

The lungfish breaches the water’s surface to breathe air. When its watery abode dries out, it propels itself with its limbs and powerful jaws to a patch of mud. It will sleep underground here through the dry season, with a slowed-down metabolism. The lungfish, which belong to the class Sarcopterygii, can survive in this state for up to five years. It is a living fossil – it hasn’t changed since earlier geologic time, and seemingly with good reason!

How The Forest Grew

Nature exists in a pulsating rhythm, where the existence of one species is entangled with the other. Among plants, seeds go through a period called masting – the synchronous production of seeds among individuals of the same species in a region. This ‘boom and bust’ production is unpredictable, and has a profound effect on the survival of species dependent on the plant, and the plant species itself. A team of scientists analysed 12 million tree-years of observations globally to understand how seeds ensure their dispersal and survival, by avoiding predators and encouraging friends.

Photo: Public Domain/Rawpixel.

They found that trees that depend on animal dispersers the most avoid masting, as predators decimate the bulk of the seeds if the tree masts. Climate and nutrient availability affect masting too. In nutrient-rich, wet environments, trees have shorter intervals between years when there is very high seed production. Conversely, species that need fewer nutrients have lower variability in seed production, and masting is more common in colder areas. Firs and oaks in North America are bountiful masters. Meanwhile, trees with colourful and rich fruit do not have too many fluctuations in production. Understanding this cycle of boom and bust among different trees can help formulate conservation strategies. In years of low seed production, practitioners can plant trees to help support animal populations.

Beyond Birds And Bees

As the Izecksohn's Brazilian tree frog Xenohyla truncata intently slurps nectar and takes bites of the scrumptious fruit of the milk fruit tree, its shiny ochre body is covered completely in pollen from the flowers. Unwittingly, it becomes a pollinator for the tree, a discovery that changed the perception of the role of amphibians in their habitat. This is the first frog, indeed the first amphibian, known to science as a pollinator. More research is required to confirm this “unique and unforeseen interaction between amphibians and plants”. Along with it, a study found that in Brazil, 95.2 per cent of the vertebrate pollinators (such as reptiles) are yet to be recognised as pollinators.

The frog is endemic to the state of Rio de Janeiro in Brazil, and has been categorised as Near Threatened owing to its small habitat of less than 20,000 sq. km. and pressures such as habitat destruction. As a frugivore (as opposed to most frogs, which are insectivores), the frog thrives on different in-season fruit. And the seeds it defecates are likely viable to grow into plants… a second way it helps to propagate the plants it relies on. When threatened, the frog puffs up its body to distort its shape and protect itself!

Did You Know?

Octopuses have the unique ability to taste what they touch through chemotactile receptors (CRs) on their arms, which they use to explore the seafloor to find food. They can keep or reject prey using just these special sensors on their arms. While they do use their eyes, they use these CRs on their arms to reach into and probe cracks that are not visible.