The Sanctuary Papers October 2022

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 42

No. 10,

October 2022

By Shatakshi Gawade

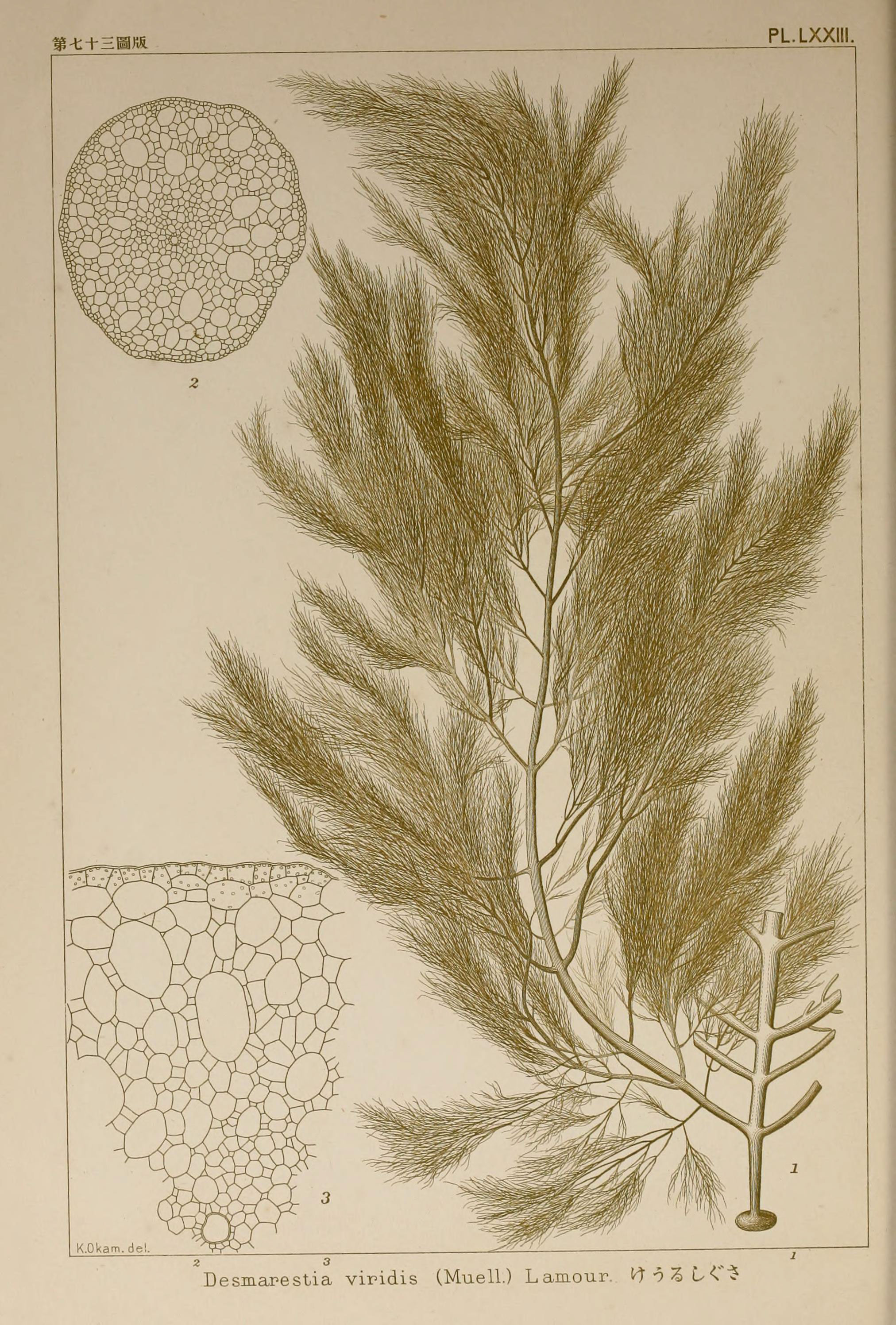

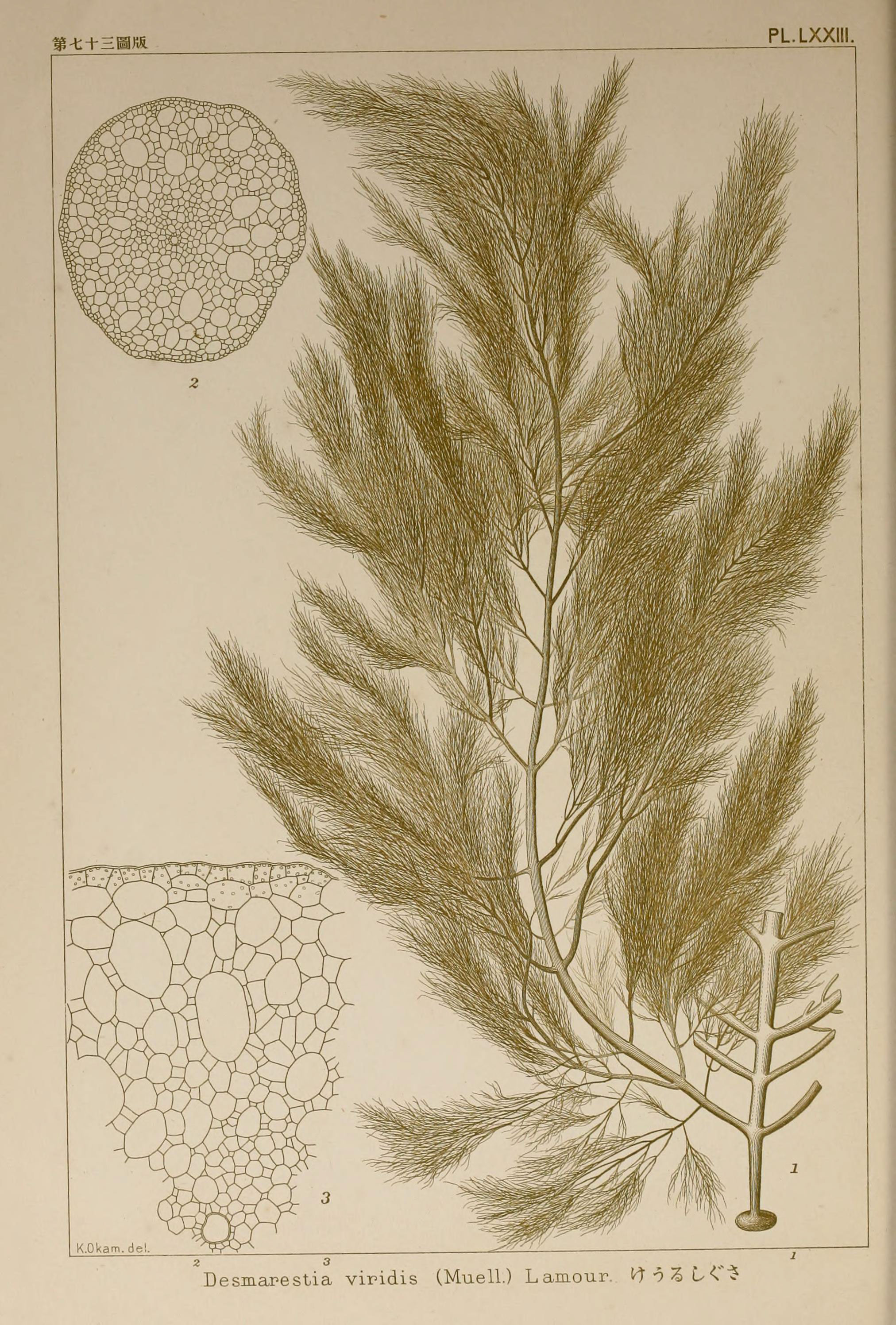

The brown seaweed Desmarestia viridis is a repellent of sorts for sea urchins that tend to consume less of the kelp A. esculenta when it is surrounded by this seaweed. D. viridis stores and produces sulphuric acid, which seems to trigger an escape response among sea urchins. Essentially, this gives kelp an extra layer of chemical protection, in addition to its mechanical protection. The presence of D virridis around kelp, which is actually an alga and not a plant as it appears to be, creates an environment with 39 per cent more species than barren areas in the ocean. These findings clarify how and why isolated kelp beds survive in different conditions, such as wave-sheltered sites.

Seaweed Desmarestia viridis. Image: Public domain

Beach Romp

Much like turtles that travel to a beach specifically to procreate, grunion fish come ashore to mate and lay eggs. The females burrow into the sand, their eyes and fins poking out, the males wrap themselves around the females, and the fun begins! Thousands of these fish flop their way to the beach, gathering so close that there is no space to walk among the glistening silver bodies. Once through, the fish wiggle their way back into the ocean, after the female lays close to 3,000 neon-orange eggs. When the tide is high, the eggs hatch, and a new batch of grunion make their way into the world. ‘Grunion runs’ were first described at the beginning of the 20th Century.

This rare species plays a vital role in the food chain on shore for birds such as herons, and in the ocean for seals, larger fish, dolphins, and more. Besides this, not much is known about their three to four year life span, and the ticking bomb of climate change is likely to shorten research opportunities. The fish are sensitive to the chemical composition of ocean water, which is becoming more acidic due to climate change. What is more, their eggs cannot survive high temperatures.

The grunion run, which occurs from California, U.S.A. all the way to Mexico, needs specific conditions – suitable sand coarseness, the moon and tides, and an absence of predators. Besides climate change, other threats to this species include beach erosion and the fish being picked as bait or snacks. Californian authorities have responded positively to these threats – activity is prohibited on the beach to give the amorous aquatic vertebrates an opportunity to complete their life cycle. Researchers such as biologist Karen Martin have encouraged citizen scientists to study the fish.

Grunion fish wiggle up the beach to mate, and the female lays close to 3,000 neon-orange eggs before heading back to the ocean. Image: Public domain

Winged Master Architect

Bald Eagles are skilful architects – they hold the record for building enormous nests! One such nest in Florida weighed 2,722 kg., was 6.1 m. deep and 2.9 m. wide. These birds of prey are also good planners; they build their nest three months in advance and add to the structure throughout the breeding season. To provide extra protection, they line the bottom of their nest with their own feathers. Both male and female bring material, though the female does most of the construction. While they prefer using sticks and branches from the vicinity, they are also known to hold branches in their talons and fly from a mile away. These are interwoven with soft materials such as grasses and mosses. They also reuse the same nest over several years! One nest was observed to be in use for 34 years, until the tree fell down.

The location for the nest is important too – they prefer building in the tallest coniferous deciduous tree, which gives them a sweeping view. The birds prefer a site near a waterbody to easily hunt fish for their young. But the absence of tall trees doesn’t deter some eagles that have been know to build their nests at secure locations in northern Canada and Alaska on the ground. Understandably, Bald Eagles will avoid heavily ‘developed’ areas.

Much like vultures in India, Bald Eagles used to be victims of pesticide use, which caused reproductive failures. They were also shot and trapped, and by the mid-to-late 1900s they were highly endangered. It took a the ban on DDT (dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane), a commonly used pesticide, coupled with proactive conservation actions to enable the iconic raptors to make a spectacular recovery.

Bald Eagles hold the record for building enormous nests! Image: Public domain

Did you know?

The oldest intact heart to be discovered is 380 million years old! Generally, only bones get fossilised. But the soft tissues – heart, stomach, intestine, liver – of the prehistoric Gogo fish survived on account of minerals in the rock formations where it was found in Western Australia. Interestingly, the specimen reveals a crucial step in human evolution, including our jaws and limbs. A ‘jaw-dropping’ discovery indeed!

Miracle Water Bear

Tardigrades can survive for decades without any water at all. These microscopic animals, aka water bears, gain this ability from unique proteins, which convert cells into a gel and prevent cell membranes from collapsing. Such a protein hasn’t been recorded in any other desiccation-tolerant organisms, nor has the strategy been seen in any other species.

Their segmented, bear-like appearance belies their tough outer cuticle, which serves as an exoskeleton. These plump, eight-legged animals expel water from their body, then turn into lifeless balls. In this state they can live without food and water for 30 years, and survive extreme temperatures and pressures. Aptly, they are known as ‘extremophiles’. When the environment becomes suitable, tardigrades un-ball themselves and continue with their life! This is known as cryobiosis, a state in which metabolic processes stop... only to be resumed later.

There are 1,300 species of tardigrades documented from vastly different ecosystems including the deep seas and sand dunes. They range in size from 0.05 to 1.2 mm. And scientists believe that tardigrades have existed on Earth for as long as 400 million years before dinosaurs made their appearance.

J.A.E. Goeze, who first described tardigrades in 1773, wrote, “Strange is this little animal, because of its exceptional and strange morphology and because it closely resembles a bear en miniature. That is the reason why I decided to call it little water bear.”

Tardigrades can survive for decades without any water because of unique proteins, which convert cells into a gel and prevent cell membranes from collapsing. Image: Public domain/DBCLS

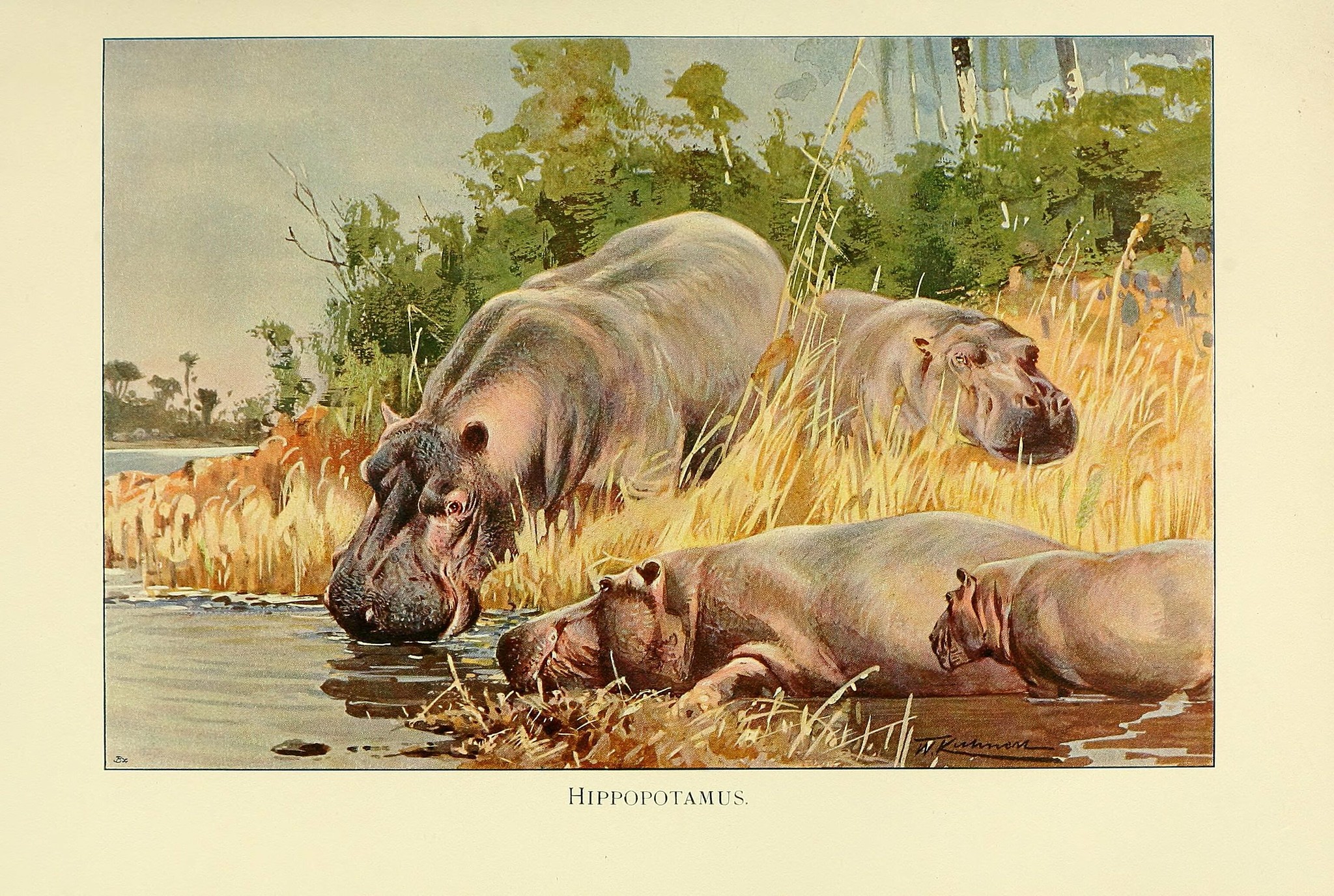

Hello Hippo

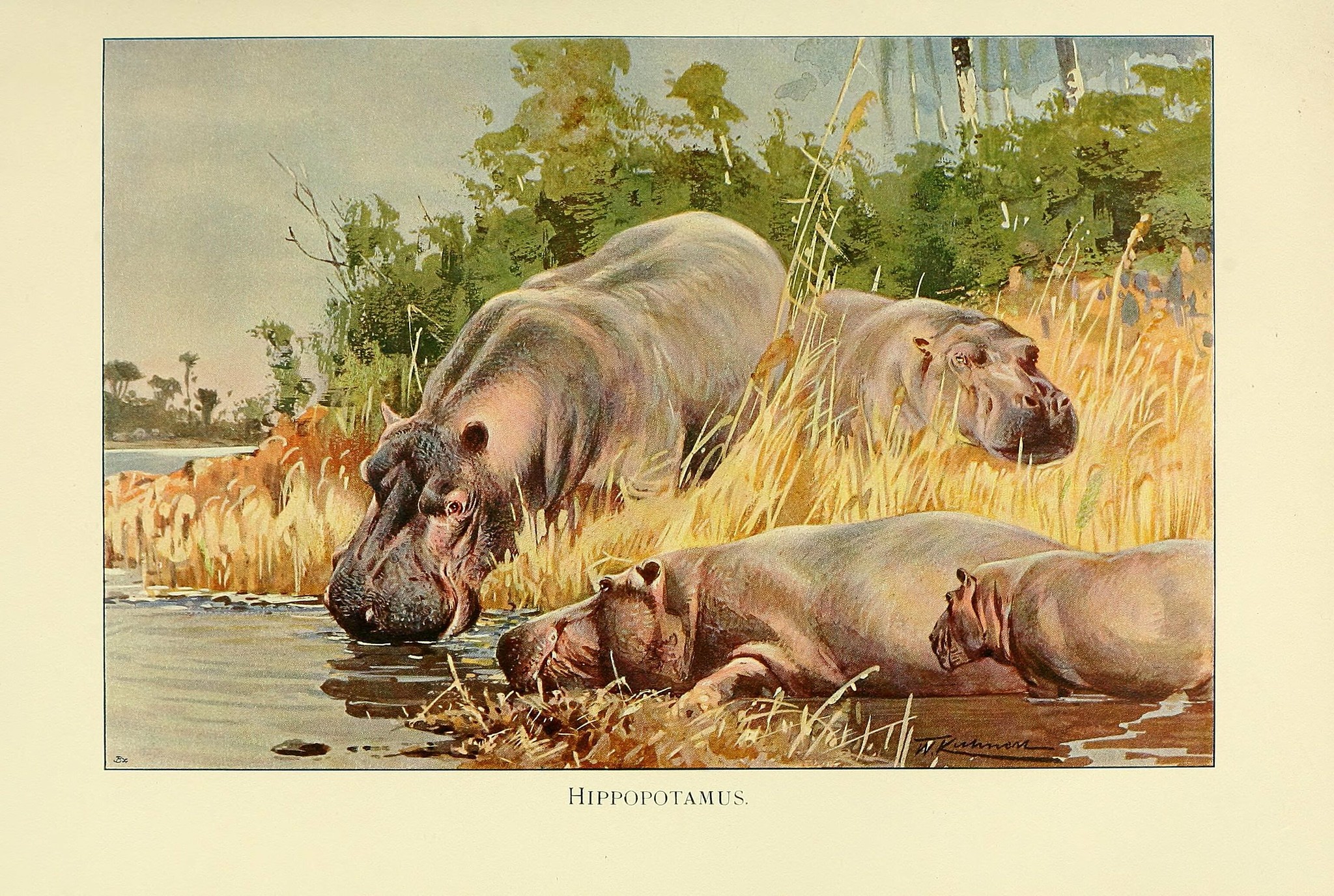

Turns out, the rotund hippopotamus is quite a talkative animal! They have a battery of sounds for communication and as identity signals. They call back when they hear from members of the same pod (group), but exhibit aggressive behaviour by spraying dung when they hear unfamiliar hippos. The study of their calls – squeals, grunts, wheeze-honks and, bellows – suggest that hippos are territorial. Their wheeze-honks can be heard upto one kilometre away. Understanding their vocalisations and perception of calls can be applied to conservation efforts... by familiarising hippos that are about to be relocated to the calls of individuals in the new area.

Another critical factor for hippo conservation is their movement pattern. Hippopotamuses, native to sub-Saharan Africa, stay dunked in water throughout the day to avoid the harsh sun and dehydration. They venture onto land at night to graze on grass. Researchers recommend buffer zones around rivers, to prevent human-hippo conflicts. Though they are herbivores, hippos are considered among Africa’s most dangerous animals. Conflicts between these semi-aquatic mammals and humans have resulted in the deaths of around people each year in Africa, according to a 2016 BBC report. That’s much more than deaths caused by lions.

Hippo populations are impacted by anthropogenic disturbances such as the over-extraction of water, which dries up their riverine ecosystems and forces them to migrate to waterholes. Waterbodies with a high density of hippos are loaded with a surplus of nutrients from their dung, which reduces insect and fish diversity. A cascading impact!

Understanding hippo vocalisations can be applied to conservation efforts... by familiarising hippos that are about to be relocated to the calls of individuals in the new area. Image: Public domain/F. Warne

Did you know?

A Burmese python can consume prey up to six times larger than similar-sized snakes. Apart from the size of its head and body, the evolution of super-stretchy skin between its jaws allows the reptile to open wide and swallow whole animals as large as deer. The bigger its prey, the more energy the python will derive from it. Pythons rarely attack humans.

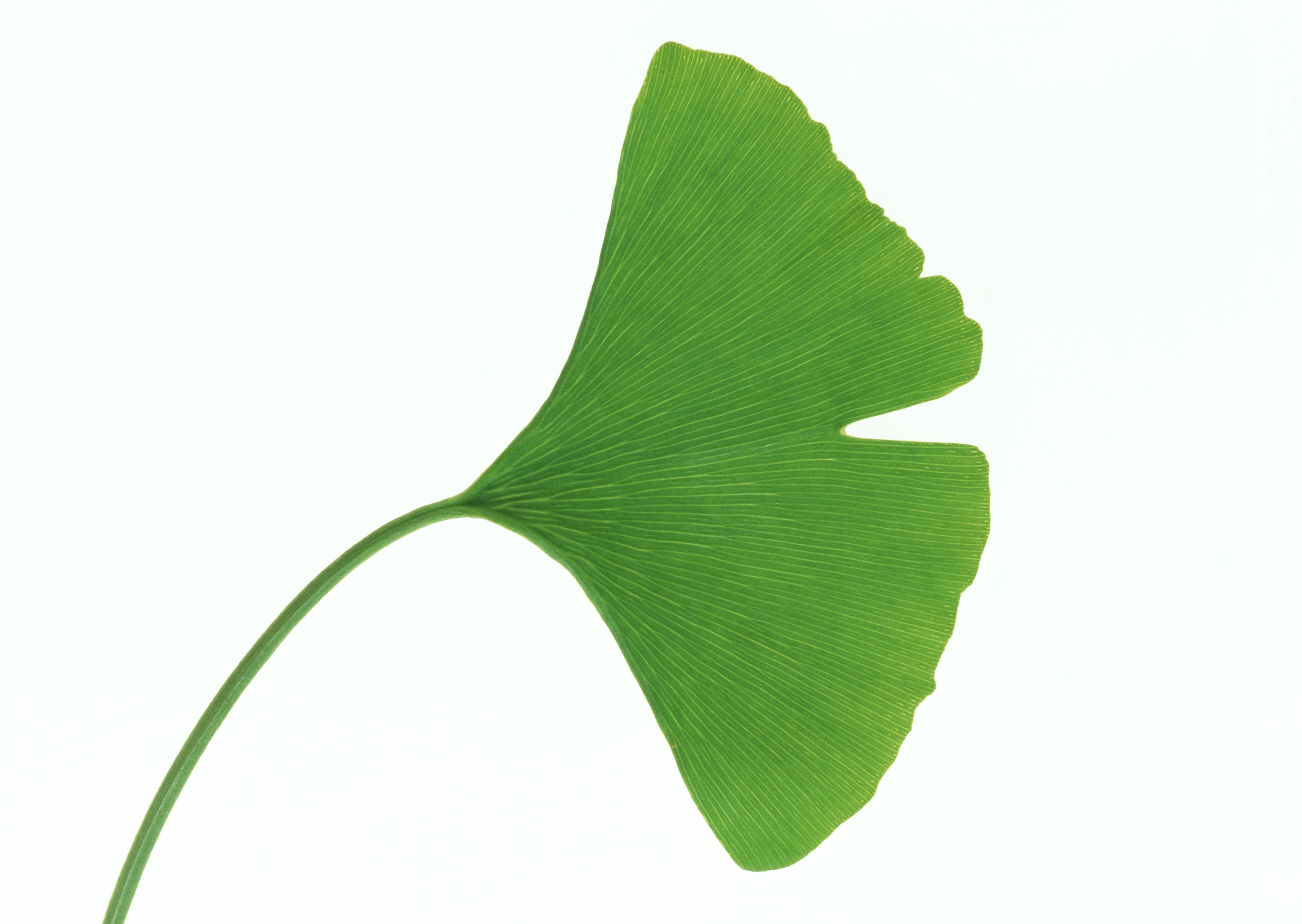

Unchanged by time

From living with dinosaurs to jostling with pedestrians, the Ginkgo biloba tree is unique – it is a ‘living fossil’, having remained unchanged from geologic times... like the horseshoe crab. The earliest fossil record of a ginkgo leaf is 270 million years ago. It is the only species in its phylum, and has no known relatives.

It’s not lonely by any means. Ginkgo biloba trees are found in China, all over Seoul and Tokyo, and also along Manhattan streets. However, the tree’s range in the wild has reduced drastically from being present worldwide to just two locations in Southern China. Cultivation in China’s temples 1,000 years ago and its travel to Europe and other parts of the world appear to have saved the tree from extinction.

The ginkgo tree has delicate, fan-shaped bright green leaves which turn golden yellow in fall. The spreading canopy of this attractive deciduous tree makes for good shade. It is a hardy species, resistant to environmental stresses including pollution, pests, lack of oxygen, and excess salinity. Some ginkgo trees are over 1,000 years old. The female ginkgo produces smelly seeds, which can be eaten, and are also used medically in China. In the West too, ginkgo leaves are consumed as health foods.

Ginkgo biloba trees are known as ‘living fossils’. The earliest fossil record of a ginkgo leaf is 270 million years ago. Image: Wikimedia Commons

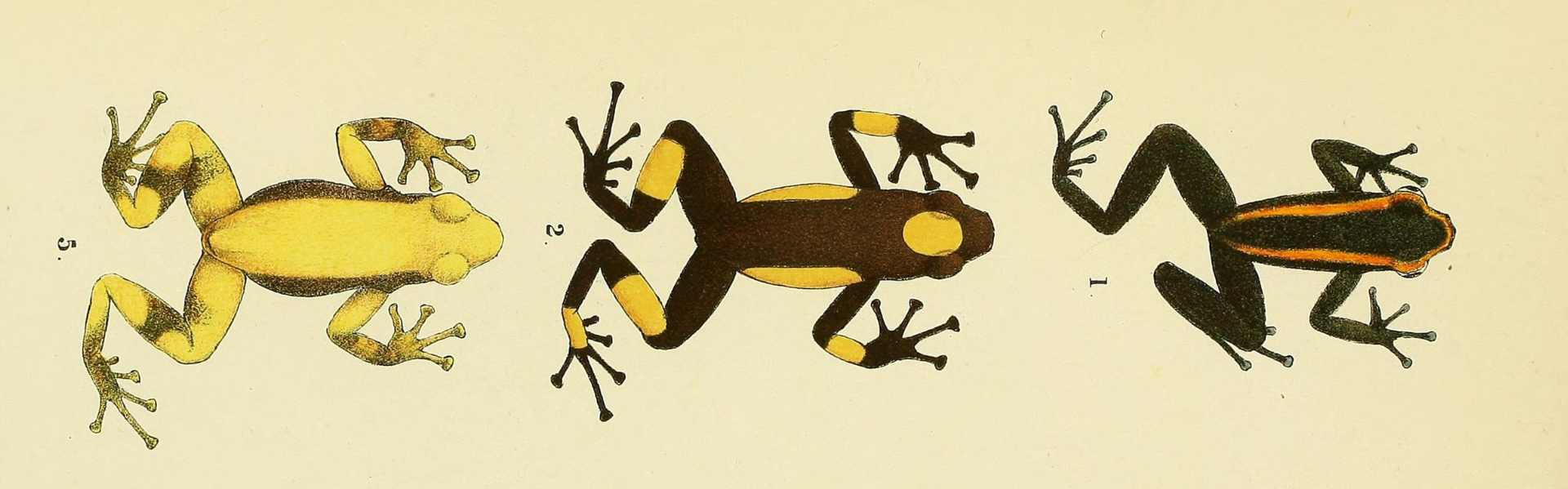

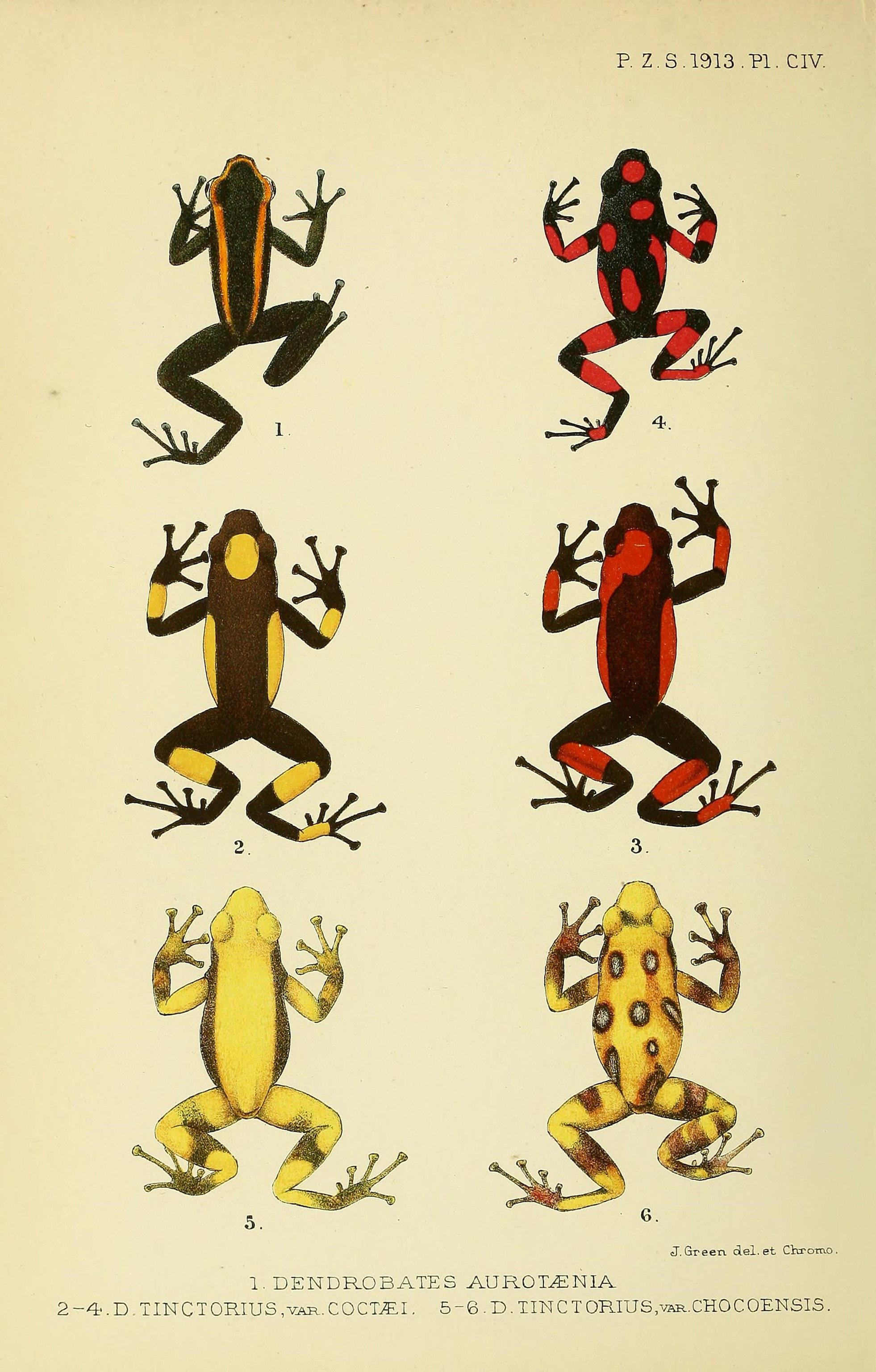

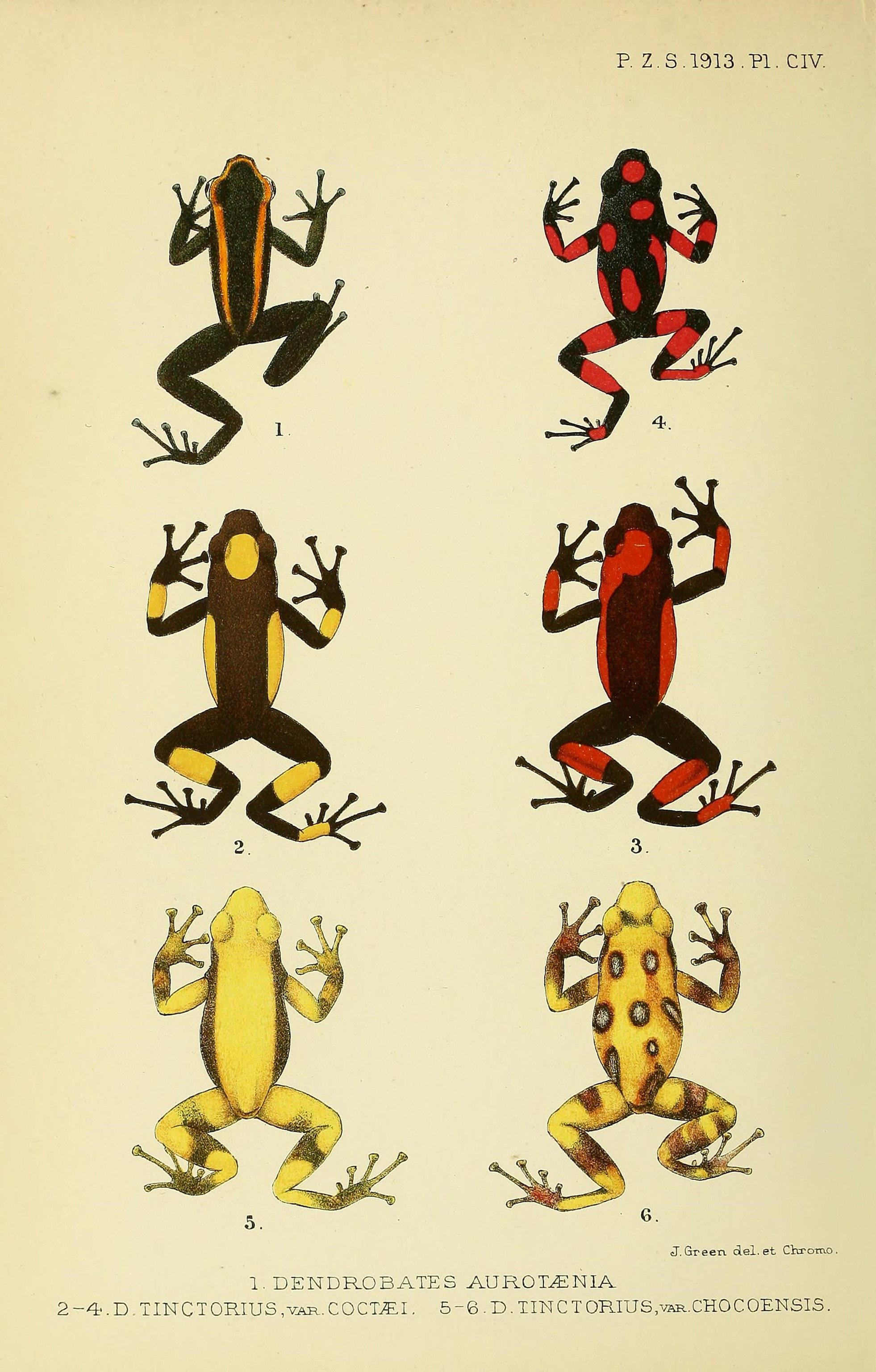

What’s your poison?

The fabulously coloured poison dart frogs stand out in foliage, using their colours to warn predators of their toxicity. The secret sauce of their poison is even smaller than the five centimetre amphibians – ants! These frogs, as well as Mantella poison frogs, can store the toxic alkaloid molecules found in ants, in their own skin glands with no harm to themselves.

Ants in turn, either make these alkaloids or obtain them from the plants they eat. Thus, captive frogs do not have this toxic defence in the absence of an ant diet, and the composition of the toxin varies based on their location. The compound is called ‘batrachotoxin’, and it interferes with the body’s nervous system.

There are more than 175 species of poison dart frogs, and they inhabit warm, moist rainforest floors in South and Central America. The frogs’ colourations vary from bright yellows, and blues to oranges, greens, and reds. This colour riot among different populations may have resulted from separation for 10,000 years.

Their lethal nature has been known to indigenous people in South and Central America who use the poison on dart tips for hunting. It is so potent that a dose of less than 0.1 μg. will cause muscle contraction, convulsions and death. Alkaloids from these frogs have also been used to make painkillers.

Poison dart frogs use their bright colours to warn predators of danger, and get their toxicity from the ants they eat. Image: Public domain/Zoological Society of London

Did you know?

European moles can shrink their brains. These small, subterranean mammals do this to save energy during the coldest months, especially when food supply is short. They can reduce the size of their brains (energy-expensive organs) by 11 per cent in winter and regrow it to four per cent by summer. Other mammals that possess this ability – known as the Dehnel's phenomenon – are weasels and stoats.