Treacherous Links

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 36

No. 10,

October 2016

By Nicole Benjamin-Fink

In the last couple of decades the illegal wildlife trade has begun to finance terrorism, insurrection and the mafia on a scale never before witnessed. The operatives for this bilious wildlife trade are common to the trades in narcotics, arms and human trafficking. Nicole Benjamin-Fink connects the dots using rhinos as her case study, while underscoring why cooperation between governments, the United Nations, local authorities, NGOs, law enforcement agencies and communities is vital to tackling this behemoth.

Photo: Vinayak Yardi.

From Al-Qaeda, to Boko Haram, to ISIS, and beyond, what interlinks the twin towers in New York city, coffee shops in Sydney, nightclubs in Paris and Orlando, airports in Istanbul, girls’ schools in Nigeria, and restaurants in Israel and Syria?

These have been ‘success’ stories of terrorist attacks.

Terrorist groups require manpower and resources; have you ever wondered about the source of these renewable resources? There is a global revolving door between the operative networks involved in the illegal trade of wildlife, arms, narcotics, and human trafficking. Terrorism utilises endangered animals as trade commodities for promoting violence and fear with the ultimate goal of eliminating entire cultures. But first, let me share with you the road that led me to seek to disentangle this linkage.

I spent four months collecting data to quantify the impact of various wildlife management policies on the probability of hybridisation between black and blue wildebeests in South Africa. During this time, I extracted DNA samples by bio-darting animals from a low-flying two-seater helicopter or the top of a baki. Because of the extreme South African heat, handling of wildlife is permitted only during the early hours of the day. Luckily, I was able to consume large amounts of coffee. At the end of a fortnight-long expedition, my research assistant, Theo, and I headed back with our samples to the genetics lab. As we left the private ranch in Mpumalanga, he asked me if I was interested in seeing “something”. I was keen.

Mpumalanga is composed of grassland alongside a network of hundreds of lakes and rivers. It encompasses two of South Africa’s primary rivers, the Vaal and Pongola. The time was about 17:00, and the sunset changed the colours of the landscape with every passing moment. I spotted in the distance two boulder-like features and assumed that we were on our way to watch an amazing sunset on the African savannah. Feeling the drop in temperature and enjoying the silence such moments have to offer, I only occasionally glanced through the windshield to glance at the grey boulders that became more and more distinct with proximity. We stopped within three metres of these ‘boulder-like’ images, situated in the golden Highveld Grassland. The huge boulders took the form of three distinct rhino silhouettes. The setting took my breath away, and I gazed at them in complete silence, appreciation, and humbleness while they grazed upon the golden grass, occasionally lifting their heads. This was the first of my many encounters with these majestic creators in their natural habitat. I would later learn that these very three white rhinos met a horrible fate - wildlife terrorism.

High Returns – a challenge

The term wildlife crime defines any activity that involves illegal trade in protected wildlife and plants. It is primarily driven by a multifaceted web of socioeconomic variables, political instability, and ineffective law enforcement. It is directly dependent on the black market. Although interlinked, wildlife terrorism is a completely different phenomenon. In the case of rhinos, it refers to the killing of individuals who have been dehorned (a conservation initiative designed to deter poachers by removing the driving factor that initiates the poaching process; the horn itself). The slaughter of a dehorned rhino does not yield any economic reward. It is driven by anger over lost income. It delivers a message to wildlife authorities, illuminating the difficulty in combating wildlife crime by preventative management strategies.

The rhino, an animal that has been 50 million years in the making, is on track to be wiped out during our generation. A correlation can be made between a decrease in demand for horn usage in Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) from 1990 to 2006, the relatively low supply (i.e., on average 23.25 rhinos were poached per year in India and 14.6 per year in South Africa during this same time period), and the drop in prices (US $200-500 per kg.). However, more than 200 greater one-horned rhinos were poached per year in India between 2007 and 2015; in South Africa, 688 black rhinos were poached in 2007 and 1,215 in 2014. The timing of these astronomical increases overlap with (and may therefore be considered a result of the market adjusting for) a prominent Vietnamese politician claiming that rhino horn consumption cured his cancer. His announcement resulted in the reestablishment of horn usage in TCM. These statistics are alarming, especially in light of governmental officials estimating that 10 per cent of all poaching events

go undocumented.

This year, Kenya hosted the largest-ever ivory burn that also saw the destruction of over one tonne of seized rhino horns. Photo: Mwangi Kirubi/Public Domain.

The Buyers’ Incentive, from India to Africa

The typical buyer’s incentive to acquire rhino horn is rooted in their belief system. Worth more than its weight in silver, gold, and even cocaine, rhino horn artifacts act as symbols of an exclusive socio-economic status in China, Vietnam, and Yemen (where it is used to make dagger handles). Rhino horns are also used in TCM, based on the belief that by consuming an animal of high potency, one gains its power. In addition to its claimed ability to cure cancer, it is perceived to act as an aphrodisiac, and when mixed with alcohol, it eliminates the effects of a hangover. This is despite the fact that the pharmaceutical industry has conducted extensive research and yet failed to identify any chemical component that supports these theories. In fact, the tissue structures that make up a rhino horn are keratinous, just like the papillary epidermis found in horse hooves or human fingernails. In other words, consuming rhino horn has the same medical benefits as chewing on one’s fingernails.

The greater one-horned rhino is a majestic animal; it has one horn and an armour that serves as a reminder of its ancient pedigree. When a plan to poach the horn of a greater one-horned rhino is put in motion, a chain of events unfolds. This includes timing, tracking, immobilising, and horn removal. The timing of the poaching itself is driven by one of two scenarios: (1) a client has been secured, or (2) circumstances are in favour of wildlife criminals not getting caught (in which case horns are stocked for future trading). For instance, during 2001 to 2005, poachers were able to infiltrate buffer zones in the Royal Chitwan and Royal Bardia National Parks, Nepal and slaughter 108 rhinos while Maoist rebel activity diverted military forces away from anti-poaching camps. More recently, in April 2016, two rhinos were poached in Kaziranga National Park, India, while park officials and guards were assigned to accompany the British royal couple. Ironically, the royal couple’s visit was designed to increase global awareness regarding rhino conservation challenges.

Rhino tracking methods differ significantly between India and Africa, largely because of local ecology and socio-economics. Kaziranga is home to the largest one-horned rhino population in the world, where rhinos live relatively close to human settlements, and, as such, poachers need not worry about tracking time or distance. In fact, the first time I spotted rhinos in Kaziranga, I was concerned about their (and my) safety, since similar abundance in South Africa can almost guarantee a dangerous encounter with poachers while game viewing. This is a country where poachers may track a single rhino for days.

Poachers in both Africa and the sub-continent employ brutal immobilisation methods, often connecting a suspended wire to a nearby high-voltage source to electrocute chased rhinos. Killing and horn removal methods vary. The cause of death of black rhinos in Southern Africa is not lead poisoning as sometimes suggested. According to captured poachers, the cost of ammo is an unwarranted item. Rhinos are chased through barbed wires that inflict painful cuts to their legs, causing immobilisation. A towel is immediately placed over its eyes, causing them to feel disorientated so that they do not attempt to get up. Finally, nooses or chainsaws hack through the rhino’s thick skin to remove the sub epidermis of the horn while the rhino is still alive. It takes a mere 48 hours for the horn to reach the black market. Sadly, it may take a long 48 hours for the rhino to die of its wounds. The slaughtering of a rhino in Kaziranga is equally disturbing. Although they live in higher densities, poachers do not risk killing more than a couple at a time because they use heavy arms that can be heard by anti-poaching guards. I was curious about how poachers can afford AK-47s, their weapon of choice. A simple search on Google reveals that these assault rifles are sold for anywhere between US $300–800 (INR 20,102–53,607), and the relevant ammunition for US $0.24 (INR 16.08). This is a worthwhile rate of return on investment (ROI) since a kilogram of rhino horn sells on the Vietnamese market for anywhere between US $65,000–100,000 (43.7–67.2 lakh rupees), and an average horn weighs between one and three kilogrammes.

Connecting the Dots

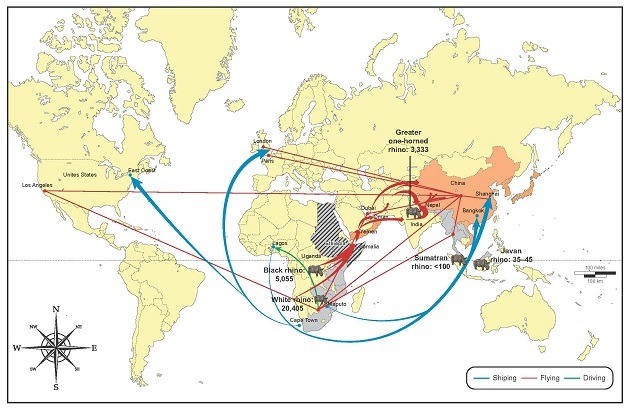

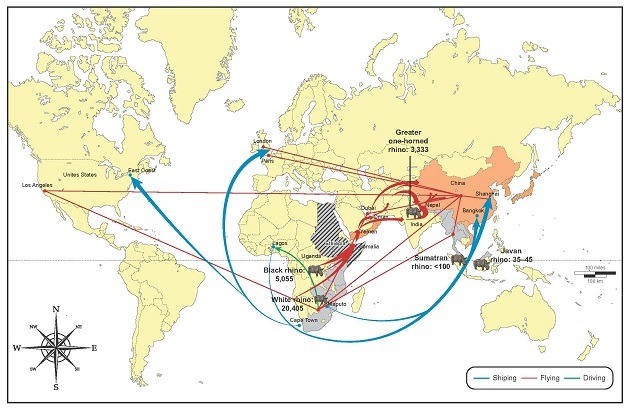

Rhino horns are smuggled to their final destination via air, sea, or overland transit (see map). There is a closed transportation network that safe-keeps its players by providing various handlers with incentivising payments at various ports. The political India-Nepal border does not act as a barrier to rhino horn smuggling. Rhinos are slaughtered in northern India and primarily smuggled overland into Nepal. The age-old societal caste system works in favour of criminal networks; traffickers are usually men who carry a portion of a rhino horn in their backpack. By then, they would have already traded part of the horn for illegal narcotics (i.e., heroin) so that the backpack will appear light to the untrained eye. To further lift suspicion, these men often travel with underage children kidnapped from proximate villages. Both man and child assume looks that are typical of a tribal or poor villager, thereby appearing inconspicuous to authorities or the common traveler. Sadly, these children are often sold to handlers within the underground sex trade.

The rhino poaching conservation problem may be approached, in part, as an economics problem formulated as a supply-and-demand equation. As long as there is a high demand, supply channels will adapt and provide the commodity, and prices will fluctuate accordingly. The poachers’ willingness to poach is driven by a delicate interplay between local socio-economics (essentially prices of food and household goods, number of children per family, feasibility of alternate livelihoods), motivation (poverty alleviation or equipping anti-government groups with illegal arms), and international socio-economics (for instance the buyers’ willingness to pay for rhino horn).

Game theory, anyone?

This caused me to ponder another important formula: cost-benefit analysis, or incentives versus punishment, if you are a game-theory enthusiast. The game is simple: how much of a risk is the reward worth? The answer lies in a complex hierarchical setting of poachers, middlemen (mainly utilised for horn handling, transport, and concealment), sellers, and, of course, the buyers. The higher the person is in the hierarchy, the higher the economic gain, while risks are diminished.

The illegal wildlife trade circulates US $7–10 billion per year (4656.925-6652.75 crore rupees); a high ROI is generated with low investment. This qualifies the slaughtering business as highly incentivising with low risk of punishment. The poachers’ dilemma is simple; is the probability (risk) of detection, capture, and conviction (punishment) worth the probability of alleviation from their socio-economic constraints (reward)? This equation is significantly biased if the poaching is driven by ideological values (as in the case of poaching for terrorism).

The punishment enforceable by law is complex. Parks in some countries, including Botswana, and Uganda, follow a ‘shoot-to-kill’ policy that states that all poachers spotted within its national and game reserves may be shot on the spot. The question of the ethics of the shoot-to-kill policy has been debated within the conservation community. Some argue that it would rather be advisable to capture such poachers to extract information and gather more intelligence to identify crime rings and leaders. However, Tanzania provides conclusive evidence that elephant poaching for ivory trade has risen dramatically since the shoot-to-kill policy was abandoned.

Conservation supporters participate in an anti-poaching awareness run in Kenya. Photo: JMK/Public Domain.

Capturing and convicting poachers is not without complexities. Under Indian law, poachers may be given up to seven years of jail time, which will weigh heavily on their families’ livelihoods. What, then, drives poachers’ willingness to risk their lives and their family’s welfare? Game theory predicts that such a high punishment will only be considered with an equal magnitude of incentives. Sadly, the extremely high ROI provides just that. Simply put, the punishment for the activity of poaching does not outweigh its incentives. An additional challenge to enforcement is the adaptive behaviour of poachers. Often, poachers will post bail and shortly thereafter change their identities and addresses, making it difficult for authorities to locate and prosecute them. Additionally, evidence gathering and documentation procedures vary, making the judicial process difficult.

The socio-economics of the poacher and the buyer

The poachers’ profit makes up a negligible percentage of the total profits, thereby making poachers themselves a disposable workforce. But who are these poachers? What are their incentives? If we identify the answers to these two questions, can we propose valid solutions to the heart-wrenching poaching phenomenon? The answer is unsatisfying to say the least. A snap shot into market forces and variability indicates that an increase in wealth in the demand countries drives the market for rhino horn more than poverty in the supply countries does. As such, poachers’ behaviour may be considered an adaptable response, rather than a driver.

Half of the world’s population lives in six countries: the USA, India, China, Brazil, Pakistan, and Indonesia. China is home to a fifth of the world’s population and the largest middle-class sector. From 2000-2015, twice as many Chinese as Americans have joined this societal sector (108.764 million middle-class people among a population of 1.4 billion), accounting for 10 per cent of global wealth. In fact, on average, a new billionaire emerged biweekly during the first quarter of 2015. Two million millionaires are estimated to emerge by 2020. Vietnam’s middle class is additionally growing at an accelerating rate and is estimated to include

30 million people by 2020. Both China and Vietnam’s role as a sink for rhino horn is predicted to expand though India and Africa clearly hold limited sources. Simple extrapolation indicates that rhino populations cannot sustain such growth in consumer demand. As such, demographics alone may be the tipping point for rhino populations that are already on the brink of extinction.

Three critically endangered white rhinos in the Highveld Grassland of Mpumalanga, South Africa. Tragically, all three individuals were subsequently killed in an act of ‘wildlife terrorism’. Photo: Nicole Benjamin-Fink.

The formula is simplistic; as wealth increases, a larger number of people can afford to buy horn commodities. However, what would happen if the demand were to decrease? It is misleading to assume that demand for this lucrative slaughter market sector are solely consumers in Asia; there is a multifaceted linkage between the low risk of punishment (ease at which rhino horn can be poached), high incentivising rewards (economic profit), and stimulating political instability. For example, in Mozambique, poachers are characteristically individuals from low-income jobs with no alternate livelihood opportunities who poach in Kruger National Park, South Africa. Their goal is to yield an economic profit and return home. Although, I must say that I am yet to hear about a retired poacher.

While poverty may be reduced by alternate livelihoods and the provision of governmental microfinancing for cottage industries, providing solutions for poachers who are driven by ‘idealistic’ terrorism is anything but straightforward. Poaching activities range from sophisticated and well-organised networks to individual, well-run criminal organisations. I have learned from personal communication that, when not fighting wars, the Sudanese militia poaches in the Central African Republic, and tribal warriors from Assam’s neighbouring states (for example Nagaland) poach in Kaziranga. These organised groups engage in the rhino horn trade with the goal to directly generate revenue to equip terrorists and anti-government groups with illegal arms, promote warlords’ agendas, and foster political instability.

Rhino horns, insurgency and cross-border terrorism

The darker side to the slaughter of rhinos is revealed by its money trail. Rhino poaching provides the financial underpinning needed for terrorists, militias, insurgents, and rebel groups in conflict hotspots across Asia, Africa, and the Middle East. Examples include Kashmir, Pakistan, Central African Republic, Eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo, Burundi, South Sudan and Darfur, Niger, Chad, Mali, Algeria, Libya, Egypt, and Israel. In fact, ISIS, a relatively young terrorist organisation with a global footprint operating primarily in Syria and Iraq, is partly funded by the oil trade and is predicted to learn from its peers; thereby, there is a high probability that ISIS will be trading in horn and ivory by the end of the decade.

The business of terrorism is straightforward: money is power. The odds for evolutionary survival are stacked against the rhino; the revolving door between armed conflicts aimed at facilitating political instability, maintained by a sophisticated global criminal network. AK-47s, RPGs, and minefields are among the long list of ammunition that takes a horrific toll on human life. Rhino horn and narcotics are utilised as currency in a reality of political instability that results in a need for arms that are unattainable through legitimate channels. Keeping in mind the low associated risk, the business of poaching is a perfect fit for terrorists who are looking to avoid detection, make a lot of money, and not face deterring consequences if they are caught.

The connection is tractable. Rhino horn smugglers crossing the India-Nepal border trade a portion of the horn for illegal narcotics. Terrorist groups like Hezbollah work with narco-traffickers. In fact, the Al-Qaeda-affiliated

Al-Shabaab group generated on average US $400,000 per month from the horn and ivory trade. The striking fact is that this accounted for 40 per cent of their annual operational budget. Such high rewards additionally encourage extreme behaviour. For example, in 2012, poachers were accused of murdering 60 African wildlife wardens.

Additional examples of terrorists financed by the rhino horn trade include Joseph Kony’s Lord’s Resistance Army in Central Africa, the Boko Haram network in Nigeria (who kidnapped and reportedly sold school girls for US $12), and Al-Qaeda in Pakistan (responsible for the attack on the Taj Mahal Palace Hotel and a Jewish Chabad house in Mumbai). Currently, rebels in Kashmir trade rhino horns for weapons to support their political agenda. As such, the national and international fight against terrorism needs strategies that effectively bring rhino poaching to a halt. Much to my relief, I have encountered good-willed people working hard in their fight against rhino poaching across India and Africa. However, explicit strategies are needed.

Ultimately, horn buyers in China and Vietnam finance terrorism. Simply put, if the government of India does not take action against organised wildlife criminal networks, rebels in Kashmir will continue to trade rhino horn for weapons to support their political agendas. Terrorist attacks often result in displaced people, human trafficking, child soldiers, killings and rapes, and genocide. Spillover effects are of vast magnitudes;

Al-Shabaab carried out a mall massacre in Nairobi, causing political instability and facilitating significant GDP economic implications due to decreased tourism. It is crucial that the rhino horn trade be curtailed in order to eliminate this lucrative source of finance for terrorist elements.

The act of rhino poaching additionally robs the people of India and Africa of their heritage. The intrinsic and monetary value placed on rhinos drives national and international tourism. In 2015, the tourism industry generated 6.3 per cent of India’s GDP, producing US $120 billion (79,833 crore rupees), by supporting 8.5 per cent of the workforce (approximately 40 million jobs). The tourism sector is predicted to grow by an average annual rate of 7.5 per cent (US $270 billion, or 179,624 crore rupees), accounting for 7.2 per cent of GDP by 2025. However, the fear of encountering poachers, coupled by the decreasing rhino populations, may decelerate such national growth.

Tracking the rhino horn trade: Smuggling methods and routes are illustrated by different-coloured lines. The chain of supply and demand is indicated by arrows. Rhino species and population numbers are positioned according to their location in the wild. Photo: Nicole Benjamin-Fink.

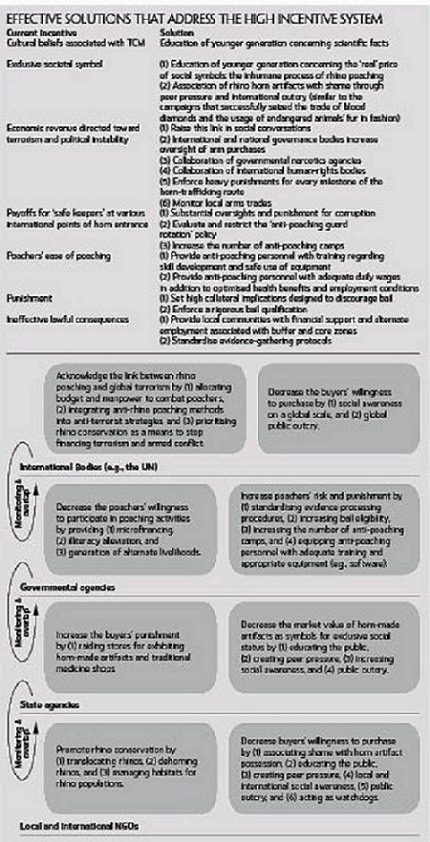

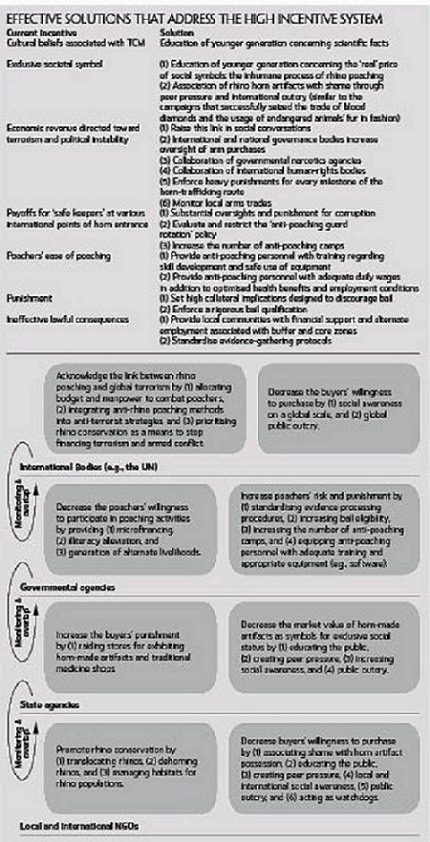

Solutions to the rhino poaching atrocity

Any plan to bring rhino horn trafficking to a halt must account for the large number of people generating demand and their motivations. Global terrorism is often combated by seizing funding sources. Rhino poaching and its by-products are too large for society as a whole, and governments in particular, to ignore. First, I caution against paths of no return. At the eye-watering prices of rhino horns on the black market, legalising the trade will most probably have a deleterious effect, as stockpiling would occur in anticipation of future scarcity. The war against poachers must be simultaneously combated on a number of parallel avenues while taking into account various motivations. These strategic guidelines should be undertaken by the appropriate bodies of various enforcement jurisdictions. Overlap in responsibility is designed to initiate dialogue and collaboration, as well as maintain transparency and accountability .

Governments can implement initiatives to promote tourism. In fact, the economic revenue generated by tourism strongly suggests that governments lead the fight against rhino poaching. Creating alternate livelihoods and providing governmental microfinancing for cottage industries, coupled with illiteracy eradication, can prove efficient at enabling poachers with alternatives to support their families financially, and thereby decrease their willingness to participate in poaching activities. Parallel to this, enforcement and prosecution should be more rigorous. This may be achieved by standardising evidence collection procedures and ensuring their implementation.

Perhaps the solution lies in the ease with which the buyers’ punishment is diminished (risk of apprehension and consequences) and at which bragging about owning a rhino horn artifact is socially accepted. The power of international public outcry should not be underestimated. Just as wearing the fur of endangered animals became unfashionable during the 1970s, and blood diamonds in 2003, so should flaunting the horn of a dead animal in 2016.

Solutions to poaching must engage with issues of broader regional stability within a wide political context. Revenue generated from rhino horn facilitates the trade of narcotics and illegal arms, promoting regional and global political instability. We can all agree that the process of hacking a horn is inhumane. Objectively speaking, the implications of the rhino horn trade are terrorism activities, displaced cultures and gross human rights violations. The path of generating revenue from rhino horns and directing it towards terrorism should be addressed at various levels. The fight against global terrorism is too dangerous to lose; it must include avenues to halt operational funding. Effective political and military strategies must include procedural steps towards stopping rhino poaching activities.

Have blood diamonds been replaced by blood horns?

Over the past nine years, I have teased out information from the complex and multilayered wildlife hunting and trafficking phenomenon. I have also learned that it makes for uncomfortable conversations at the occasional social gathering, perhaps because factual details are not widely known. A primary example of the impact of international outcry concerns blood diamonds. There is an established link between blood diamonds and the funding of warlord activities, armed conflicts, and civil wars across Africa (e.g., Sierra Leone, Liberia, Angola, Côte d’Ivoire, the Central African Republic, and the Democratic Republic of Congo). Funds generated from the blood diamond trade, much like those generated from the rhino horn trade, often result in gross violations of human rights by terrorist groups (as in Kashmir). Yet, it took two decades for the international community to be willing to acknowledge this link and to meet this problem head on. The act of continuously bringing this devastating linkage to the forefront of conversations was impactful; UN resolutions and the Kimberly Agreement in 2003 sought to halt the ease by which blood diamonds reached the international market through a procedural framework that requires diamond sellers to provide diamond buyers with documents verifying their legitimate origin. Society as a whole cannot afford to ignore its impactful footprint.