Washing Away The Subansiri Elephants

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 46

No. 2,

February 2026

By Neeraj Vagholikar

Power generation patterns from the massive 2,000 MW Subansiri Lower Hydro-electric Project will result in flash-floods downstream, running the risk of literally washing away elephants, human beings and other life-forms. A January 2024 report of the Wildlife Institute of India (WII) raised the alarm, which was inexplicably ignored by the Standing Committee of the National Board for Wildlife (SCNBWL) for two years. Meanwhile, the turbines in the project have begun commissioning phase-wise, starting December 2025.

We have to try our best to save lives… elephants, humans and other creatures,” Keshoba Krishna Chatradhara tells me with a sense of urgency. Bhai, as Chatradhara is popularly known, lives downstream of the 2,000 MW Subansiri Lower Project constructed at the border between Arunachal Pradesh and Assam. Arunachal Pradesh forests will primarily be submerged, while the dangerous, downstream effects will be suffered by the state of Assam.

Having spent over two decades raising concerns about the serious environmental and social impacts of this project on the Subansiri river and its surroundings, Bhai says, “Ideally the project should not have been built at this site, it is an environmental disaster. But now that it is here, we do not have the luxury to be mute spectators. We need to engage with decision-makers to mitigate the impacts to the extent possible.”

For example, he insists that at the very least, power should be generated while maintaining downstream flows as close to natural flow patterns as possible. Not in a manner it is currently planned, causing drastic water flow fluctuations in the immediate downstream on a daily basis, putting all those who have a relationship with the river at serious risk.

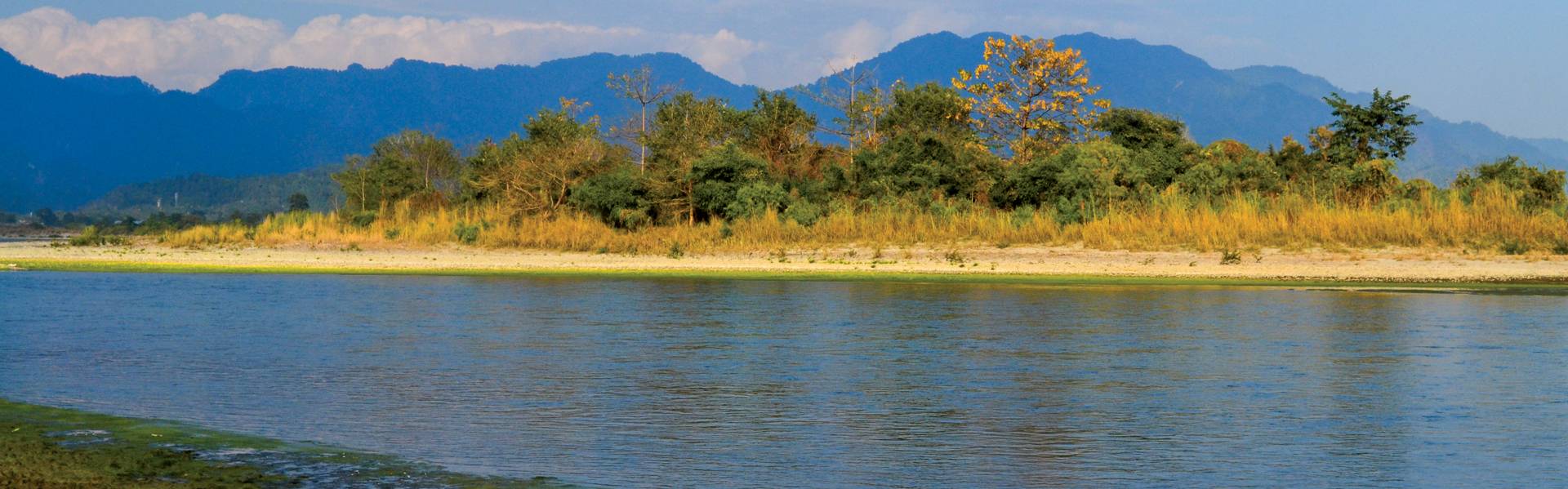

The 2,000 MW Subansiri Lower hydro-electric project, which has come up on the Assam - Arunachal Pradesh border after over two decades of environmental subversion. The first turbine of the project got commissioned in December 2025. The Dulung - Subansiri elephant corridor in the downstream (top of photograph) faces a serious threat from massive water flow fluctuations owing to power generation patterns. Photo: NHPC Ltd.

WII Alarm Falls On Deaf Ears

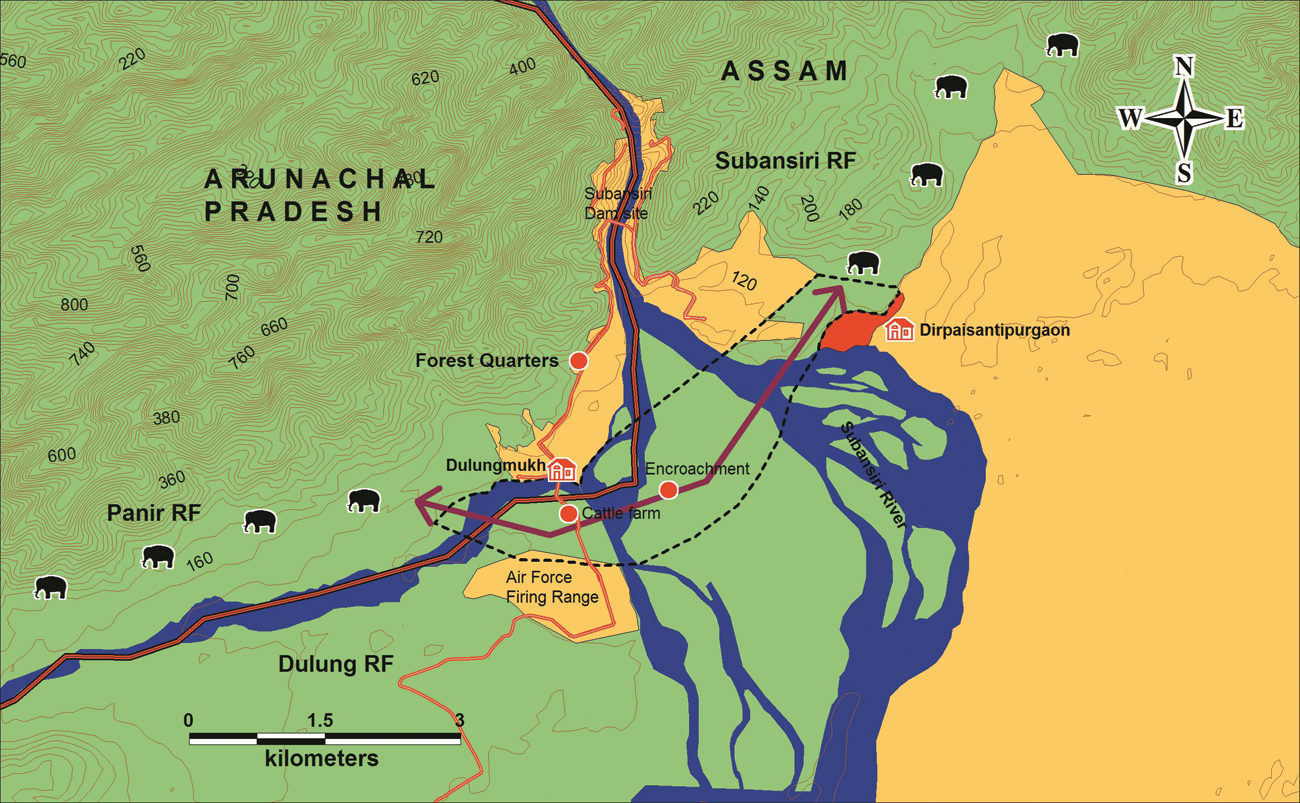

In January 2024 the Wildlife Institute of India (WII) submitted an important report to the Standing Committee of the National Board for Wildlife (SCNBWL). This outlines a plan for ensuring safe passage for elephants between the Panir and Dulung Reserved Forests (RF) on the west bank in Arunachal Pradesh and Assam respectively, and Subansiri RF on the east bank of the river in Assam, downstream of the Subansiri Lower Project. This passage across the Subansiri river is known as the Dulung – Subansiri elephant corridor. The last recommendation of this report rings alarm bells: “Drastic modulation of river flow does not appear conducive to the elephant corridor. Based on peaking scenarios shared by NHPC, it appears that hydro-peaking would be similar to flash floods. Thus, it could result in elephants (particularly calves) getting swept/separated away from the herds. A few incidents, such as calves getting swept in the river could possibly trigger behavioural avoidance in using the riverfront.

Further, the risks posed by modulation induced by hydro-peaking on river islets remain unknown. If peaking changes the chapori dynamics and affects their vegetation, the elephant corridor might be lost as some of the chaporis act as habitats. Hence it is recommended that the project proponent must restrain from hydro-peaking operations until a multi-seasonal hydrological modelling study in relation to impacts on elephants and its habitat are carried out.”

Hydro-power plants do indeed have the flexibility for quickly ramping up electricity generation to meet peak loads – the maximum electricity demand – at certain times of the day. Such operations are called ‘peaking’ or ‘hydro-peaking’. But as the WII report warns, it is a recipe for disaster in scenarios where ecologically sensitive areas are downstream. Both wildlife, such as elephants, and the habitat, such as the chaporis – riverine islands – will be impacted. WII’s mandate was to look at the impact on the elephant corridor, but such flow fluctuations will put at risk all life-forms, wild and domestic, as well as human beings, whose lives are intricately linked with the river. For example, in the case of the Subansiri Lower Project, hydro-peaking will take place during the non-monsoon period on a daily basis and downstream flows will fluctuate cyclically between 240 cumecs (cubic metres per second) during non-peaking hours, when one turbine runs at part-load, and a whopping 10-fold increase to 2,579 cumecs when all eight turbines are operated during hydro-peaking.

The up-ramping will cause water levels to go up by 1.5 to two metres (approximately 5 to 6.5 feet) in the first 40 km., with it being like a flash-flood in the near downstream, where the elephant corridor is. As the minutes of the 77th meeting of the SCNBWL held on January 30, 2024 record: “The Director, WII mentioned that during peaking, when all the eight turbines would be functioning, there would be a sudden increase in the flow of water from the dam up to 1.5 m. high, which would take away the elephants crossing the river.” But one day before this meeting of the SCNBWL, officials of the project developer, NHPC Ltd., met the Member Secretary of the wildlife board and “requested” that this vital recommendation of WII not be accepted. Two years down the line, as of the end of December 2025, the SCNBWL in its deliberations continues to maintain a stoic silence on this critical WII recommendation. Meanwhile, in December 2025, the project began phase-wise commissioning of its turbines. All eight turbines are expected to be commissioned in the financial year 2026-27.

Construction-related infrastructure and activities have fragmented the elephant corridor, which needs urgent restoration. But the big looming threat is the water flow fluctuations due to power generation patterns called hydro-peaking, which will cause a flash flood-like scenario in the immediate downstream. A 2024 WII report stated this will wash away elephants crossing the river. Photo: Rights of Passage 2017/Wildlife Trust of India.

The Subansiri Subversion

Much water has flown down the Subansiri river in the past two decades as it witnessed a pitched battle on different aspects of this project: its siting; impacts on forests, wildlife and biodiversity in the upstream and downstream; dam safety and design; geology and seismicity; flood control and livelihoods. With compromised green clearances, the project wove its way through: opposition from the downstream communities leading to stoppage of work; multiple expert panels reviewing it; changes in design and operation acknowledging a few flaws; dilution of stringent wildlife conditions after work was well underway; violations, and court-room drama.

While the nation celebrated the commissioning of the first of eight units of this massive hydro-power project as an engineering marvel in December 2025, the question to ask is: Have we stopped caring for revered and heritage animals such as elephants, which will lose territory, migratory routes and lives? Despite knowing that the same amount of power can still be generated throughout the day, without resorting to life-threatening hydro-peaking for a few hours in this specific project?

Assam-based conservationist Bimal Gogoi, writing to the SCNBWL on December 8, 2025, urging it to commission the hydrological study recommended by WII for the Subansiri Lower Project, gave examples of other hydro-power projects that will not carry out hydro-peaking for various reasons: “The same SCNBWL, while granting wildlife clearance to another mega hydro-power project proposed on the Lohit river, at the cultural heritage site Parshuram Kund in Arunachal Pradesh, the 1,750 MW Demwe Lower project, has disallowed peaking operations until detailed downstream impact assessment studies on sensitive downstream ecosystems and species, including the critically endangered Bengal Florican and Gangetic river dolphin, are carried out. Further owing to other technical and geological reasons, four hydro-power projects upstream of Demwe Lower on the Lohit river – Demwe Upper Stage I, Demwe Upper Stage II, Demwe Upper Stage III and Anjaw – will be barrage-based projects that carry out no hydro-peaking.”

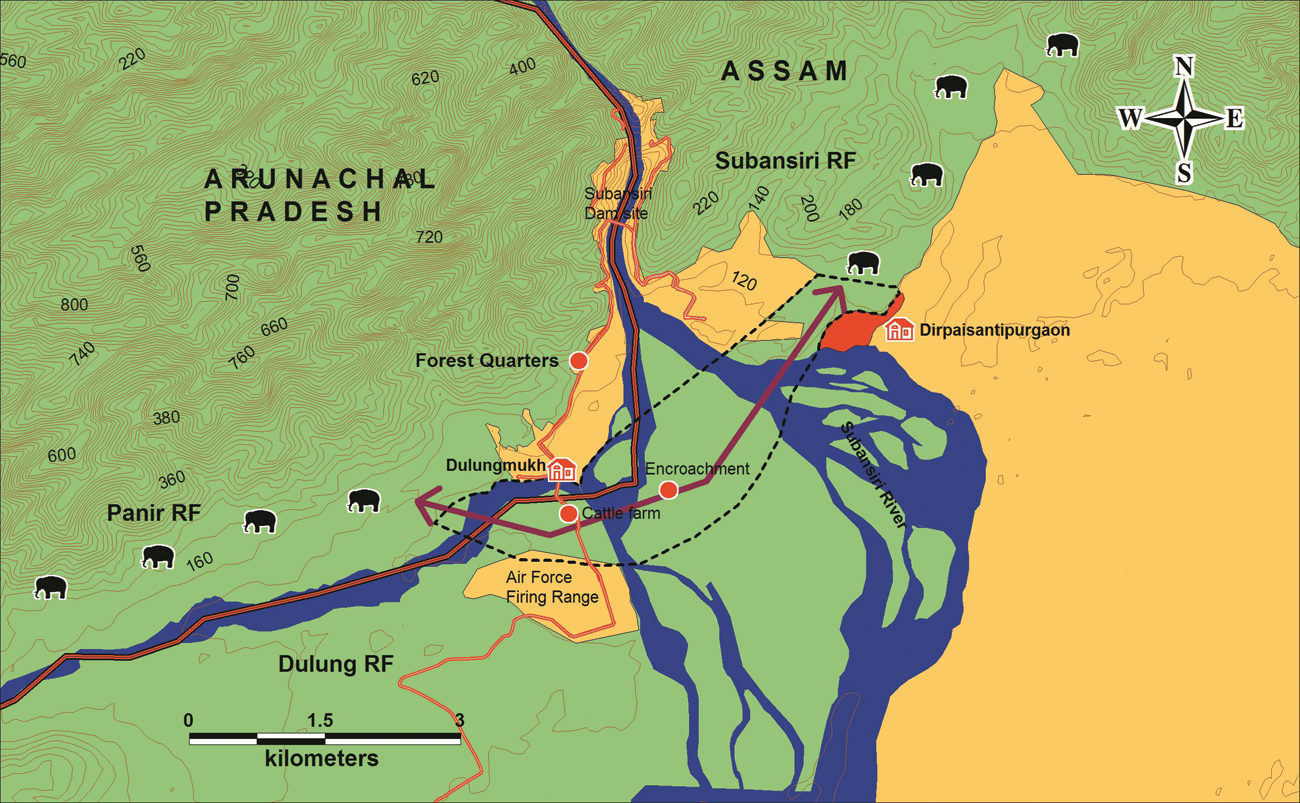

The Wildlife Institute of India has asked for operations to be restricted until they carry out a detailed multi-season hydrological modelling study to assess impact on elephants and their habitat. The Standing Committee of the National Board for Wildlife has sat on these recommendations for two years, even as the turbines have begun spinning in a phase-wise manner since December 2025. Photo: Neeraj Vagholikar.

Elephantine Lies

The physical obstructions to the elephant corridor because of ancillary infrastructure and activities of NHPC Ltd., and resulting human-elephant conflicts in surrounding areas, have been raised over the years in various official reports. However, the issue of hydro-peaking was not shared with decision-makers when the project received upfront environment, forest and wildlife clearances. Bittu Sahgal, conservationist and Founder-Editor of Sanctuary Asia, was part of the sub-committee of the erstwhile Indian Board for Wildlife (now NBWL), which conducted a site visit in 2002, before the 2003 wildlife clearance to the project. He says, “We were kept in the dark about the massive water flow fluctuations, which will take place downstream on account of power generation patterns. Neither was it in the Environment Impact Assessment report, nor was this shared with us during our site visit on behalf of the wildlife board.”

The nature of hydro-peaking in this project came to light only after huge public protests led to various expert review panels being set up, the last of which submitted its report in 2019, based on which work re-started on the project. The issue of very low flows got partially addressed, since the minimum flows were increased from six cumecs to 240 cumecs by asking one turbine to run at all times on part-load. However, the fact that drastic fluctuations between 240 cumecs and 2,579 cumecs would still be devastating for elephants crossing the river, as well as other life-forms, did not even find its way into official reports.

Until the January 2024 WII report, which shone a light on it, but NHPC has managed to stall its recommendation for two years. In a rejoinder to a 2005 article (Damning our Wildlife – Lower Subansiri; Vol. XXV No. 1, February 2005) written in this magazine by this author on the Subansiri Lower Project, NHPC argued: “Further, it reports the obstruction of the migratory route of elephants caused by project activities, labour colonies and boulder mining. This is inaccurate and not based on ground realities. The migratory route of elephants falls approximately five to seven kilometres downstream of the Project. At that point the river’s course is broad and its current is moderate enough to allow elephant crossings.”

It was apparently only a ‘minor detail’, well known to them, which was not disclosed by NHPC Ltd. That the moderate current will get transformed into a raging flash-flood during hydro-peaking. Something that could wash away elephants crossing the river. Irrespective of NHPC’s lies back then, SCNBWL can still ask that power is generated ensuring the ‘moderate current’, which NHPC promised us two decades ago. Will they do it?

Neeraj Vagholikar He has closely tracked environmental governance issues with respect to hydro-power projects in Northeast India for the past 25 years. He is passionate about rivers, wildlife and cultures in the region, and has authored the children’s story book ‘Saving the Dalai Lama’s Cranes.’