Wildlife Films - Voices Of Green-Heart Film Makers

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 46

No. 2,

February 2026

A Sanctuary Report

Wildlife films focused on nature have long shaped how we imagine nature – bringing fecund forests, elusive species, and fragile landscapes into our living rooms. In India, a country of stunning biodiversity and equally complex conservation challenges, these films hold great potential beyond entertainment. They can influence public perception, inspire policy conversations, and help bring focus on species and landscapes that must be protected. But do wildlife films still serve conservation in a meaningful way, or have they drifted toward spectacle at the cost of substance?

Here is what Bittu Sahgal, Editor of Sanctuary Asia, has to say about Sanctuary’s foray into the rough and tumble world of wildlife documentary production, with a focus on India.

“In the late-1980s, several years after the launch of Sanctuary Asia in 1981, Kailash Sankhala, the first Director of Project Tiger and Fateh Singh Rathore, the first Field Director of the Ranthambhore Tiger Reserve, suggested it was time for Sanctuary to reach a much wider audience. My late friend Valmik Thapar, famous for his direct one-liners, added: “How many magazines can you possibly sell? The only way to reach millions is through films.” That was the seed for Sanctuary Asia’s foray into film production. Apart from them, I was also encouraged by Hemu Panwar and a phenomenal scientist, Alan Rodgers, who advised me to focus on biogeography, not only on ‘the tiger’. I was then lucky to be taken underwing by virtually all the major wildlife conservation stalwarts of the day in India, without whom neither Sanctuary magazine nor its impactful offshoot, a 16-serial set of wildlife documentaries plainly titled: ‘Project Tiger’, would have seen the light of day.

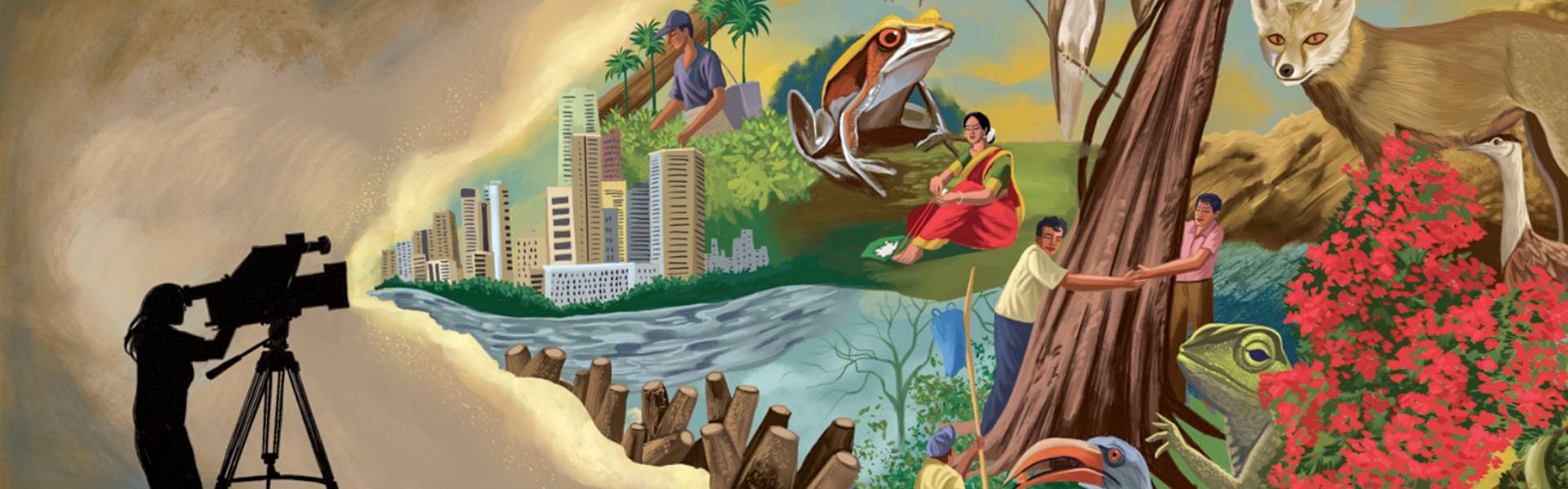

In India, a country of stunning biodiversity and equally complex conservation challenges, wildlife films hold great potential beyond entertainment. They can influence public perception, inspire policy conversations, and help bring focus on species and landscapes that must be protected. Photo: Sayan Mukherjee.

At the time, Doordarshan was the only Indian TV channel, led by Bhaskar Ghosh, a bureaucrat with a reputation for independent thinking, coupled with a rock-solid value system. I met him at his office and narrated the outline scripts I had personally written with help from my friend, the late Sunjoy Monga. I waited with bated breath for his decision for a week, then two and when I called Ghosh’s office, an assistant laughed good naturedly at my naivette and showed me a long, really long, list of producers who had been waiting for months for a slot on Doordarshan. Nevertheless, the same assistant called me back within the month saying, “Ghosh Saheb wants to meet you.” I flew down to Delhi from Bombay and in a matter of minutes Ghosh, who I met for the very first time, said: “I have checked and you have never ever produced a film. But this is precisely the kind of content that Doordarshan needs. Are you sure you can actually deliver the films on time because this is not an easy project you are taking on?” I replied: “That’s what I was asked by everyone when I started Sanctuary Asia magazine too. This is my life. I have no other purpose and I will not let you down.” Within two weeks I got a written letter approving the production of 16 documentaries plainly titled ‘Project Tiger’. I did not let him, or myself, down.

Looking back today, the production quality of our 16 documentaries was embarrassing, when compared to the BBC ‘Life on Earth’ films, presented by David Attenborough, or those produced by today’s incredibly talented Indian producers. In the event, Sanctuary’s ‘Project Tiger’ seemed to have filled a niche and the series won a viewership of 30 million people over 16 Sunday mornings (10 times lower than ‘Mahabharat’ or ‘Ramayan’!). Looking back, it was an audacious venture. Our available budgets were laughable! The money we had for cinematographers, sound engineers, editors, four Arriflex 16 mm. cameras, telephoto and block lenses, Nagra audio recorders and mikes, fluid head tripods, 16 mm. Kodak film negatives, positives, post-production, editing, and promotion was lower than the sound budget of just one BBC documentary of the day.

However, my hero, David Attenborough’s words remain etched in my heart and still drive my purpose: “No one will protect what they don’t care about and no one will care about what they have never experienced.”

I can think of no other medium that can communicate the imperative of protecting and the sheer magic of our natural heritage than film. And that is what you will hear from the handful, among hundreds of talented filmmakers on the pages that follow.

Few have reflected on wildlife filmmaking as candidly as filmmaker Shekar Dattatri, who, nearly two decades ago, in Sanctuary’s February 2007 issue, laid bare the realities behind the camera – realities far removed from the romance of the wild.

“In theory, wildlife filmmaking is quite simple. You come up with an interesting idea, write a proposal, convince someone to give you the money, obtain the necessary permits, and go off into the wilderness to shoot. When you’ve got all the footage you need, you edit the film, add music, sound effects and commentary, and voila! you have a film. In practice, however, it’s quite a different story altogether. Each one of the above steps can be absolutely grueling, and finding the funding is tough, no matter how good your track record has been or how long you’ve been in the business.

For all these reasons, and then some more, the specialised field of natural history filmmaking has never been easy to break into, no matter what your nationality is or which country you live in. The rate of attrition is extremely high and only the most persevering and talented can even gain a foothold. The odds are even higher for Indian filmmakers, who have to contend with a host of special difficulties. To survive and grow in this profession one must gain the acceptance of reputed international channels as a producer or cameraperson. But with no support of any kind, and lacking outlets for wildlife films on Indian television, filmmakers here have virtually no opportunities for gaining the experience and expertise needed to compete in the highly-crowded and intensely-competitive international arena. Although India now has a bewildering number of homegrown television channels, none of them commission wildlife programmes, which are highly expensive and time consuming to produce. Exorbitant government filming fees and highly restricted access to wildlife compound the problem, and are sounding the death knell for this filmmaking genre even before it has a chance to bloom properly.”

Dattatri’s words captured a moment when wildlife filmmaking in India stood on fragile ground – hampered by lack of funding, limited access, prohibitive costs, and almost no domestic broadcast support. His critique was not merely about logistics, but about a system that made sustained, ethical storytelling nearly impossible.

A Changing Landscape

Much of what Dattatri wrote remains relevant. Yet, in the years since, Indian wildlife filmmaking has evolved quietly but decisively. What was once a niche dominated by foreign broadcasters and educational formats has expanded into a more cinematic, emotionally layered form of storytelling, one that resonates with global audiences while remaining rooted in local realities.

Advances in technology, from lightweight 4K cameras to long-term field recording and drones, have widened creative possibilities while also encouraging more ethical practices. Streaming platforms have brought wildlife films into mainstream cultural conversation, and funding – once almost exclusively international – now flows from a mosaic of broadcasters, OTT platforms, philanthropic foundations, conservation grants, and select corporate partnerships.

This shift has empowered Indian filmmakers and production houses to tell their own stories with confidence and craft. Increasingly, the focus has moved away from exotic spectacle toward conservation impact – foregrounding coexistence, community voices, and ecological urgency. Indian wildlife cinema today sits at the intersection of art, advocacy, and accessibility, shaping not just how nature is seen, but how it is valued.

Cinematographer Madhu Ambat during the filming of ‘The Boy and the Crocodile (Dost Magarmachh)’. The film was released in 1990 and got the Silver Elephant Award at the 6th International Children’s Film Festival, New Delhi, and the UNICEF Best Feature Film Award at the International Centre for Films for Children and Young People. Photo Courtesy: Romulus Whitaker.

Learning From The Early Years

To understand how far the field has come, it helps to revisit its formative years, when filmmaking was as much about improvisation as intention, and passion often substituted for resources.

Romulus Whitaker, acclaimed herpetologist, filmmaker and wildlife conservationist, recalls his earliest experiences behind the camera, when wildlife films were built on curiosity, collaboration, and sheer persistence.

“I was involved in making ‘Snakebite’, about India’s ‘Big Four’ dangerous snakes, how to avoid getting bitten, and what to do if bitten. My mentors were John and Louise Riber, both from the same school as mine – the Kodaikanal International School, many years before. So there we were, in 1985, with a Bolex wind-up 16 mm. film camera and a simple DAT tape recorder for sound, a couple of reflectors and a rough storyboard to guide our effort to create an educational film. Luckily, the Ribers had already delved into filmmaking and so my colleague Shekar Dattatri, who, like me, worked at the Madras Crocodile Bank, was learning the art from them.

‘Snakebite’ was a ‘docudrama’, a documentary film with elements of staged scenes with ‘actors’, all of them friends from Vadanemmeli village, across the road from our Madras Crocodile Bank. We sent the completed film to the Missoula Film Festival in Montana, U.S.A. and were stunned that it got a Best Professional Film award. It also received a Gold Medal award from the British Medical Association.

This success encouraged Shekar and I to team up with our friend Revati Mukherjee, my brother Neel Chattopadhyaya who did sound, and Zai Whitaker, who wrote the scripts. Over the next few years we produced short films on the Irula snake catchers, on tree planting, and the research being undertaken at the Croc Bank. In 1989, I had this idea to produce a Tamil feature film and Zai wrote a touching story about a little village boy who befriends a crocodile. But as the story unwinds, the village is against it and in an exciting finale, the boy has to save the croc from getting killed by riding it into the sea. ‘The Boy and the Crocodile’ (Dost Magarmachh) was sponsored by the Children’s Film Society of India, and I remember visiting Bombay several times to have long conversations with Jaya Bachchan, who headed the Society in those days. Our cameraman was Madhu Ambat, who went to the U.S.A. to work for Disney, and my Associate Director was K. Hariharan, who I really relied on to hold the whole production together. The hero of the film was a teenage Irula boy, Yelmalai, and the rest of the cast was villagers except one young actress, Lakshmi, who played Yelmalai’s sister. I became obsessed with editing the film on a primitive Moviola I had bought, and would stay up almost all night viewing the rolls of film, picking out the best shots, cutting and splicing.

When ‘The Boy and the Crocodile’ was released in 1990, it got the Silver Elephant Award at the 6th International Children’s Film Festival, New Delhi and the UNICEF Best Feature Film Award at the International Centre for Films for Children and Young People. Zai and I were thrilled to be invited for the screening in Teheran and it was great to have two of the famous Irani radio announcers live-dub the voices in Farsi, and to see the reactions of the kids in the audience there. ‘Croc Boy’, as we call it, was shown at festivals in Beijing and Moscow, and televised on Christmas Eve in Norway and Sweden, what a trip!

Janaki Lenin and I went on to make a bunch more films for National Geographic, Nature/PBS and BBC and the biggest kick was the film that we made for Nat Geo in 1996 called ‘King Cobra’, which won an Emmy Award. After making our final film together in 2001 (Janaki just wanted to be a writer) called ‘Muggers of Spice Island’ in Sri Lanka, I continued my ‘big screen career’ as a presenter, doing films such as ‘Snake Hunter USA’, ‘One Million Snakebites’ and ‘Leopards – 21st Century Cats’.

All this was both hard work and a lot of fun. Today it’s all video and seemingly much simpler than those days, when we had to fight with the airport security dudes who wanted to x-ray our cans of film, and wait for days for the film to get processed to see what we had shot. Today the blue chip wildlife films are sometimes unbelievable for the fantastic macro photography and behavioural footage they get, cameramen going under the ice in the Arctic and way up into the forest canopy. But I don’t have any time for the sensational crap that some of the big channels now air on TV. I won’t mention any names, but it’s painful to sit and watch people wrestling animals, getting bitten and lost in the jungle, over-dramatising their boring adventures. As far as I’m concerned we were lucky to have done our films during the ‘golden age’, when all we needed to do was to show the world how animals behave naturally, and tell a good story.”

Whitaker’s recollection is not merely nostalgic; it maps the foundations of Indian wildlife cinema – hands-on learning, interdisciplinary collaboration, and storytelling driven by education rather than spectacle. From a wind-up Bolex camera to international film festival recognition, these early efforts demonstrated that powerful stories could emerge even from modest beginnings. Whitaker’s reflections also serve as a reminder of what has been gained, and what we risk losing, as technology advances and formats evolve.

Memory, Meaning, And Responsibility

Filmmaker Rajesh Bedi, another veteran of the field, echoes this sentiment while situating wildlife films within a broader cultural and ethical framework.

“Films and television have long been powerful storytellers for India’s wildlife. They carried jungles, rivers and elephants into people’s homes, awakening empathy and awareness. At a time when conservation was scarcely understood, visual media gave voice to voiceless species, inspiring public support and policy attention that written words alone could not achieve. When we began, there was little infrastructure, no funding, and scant recognition. Wildlife films were seen as indulgence rather than necessity. Today, the ecosystem is vibrant – festivals, awards, and audiences celebrate conservation cinema. More importantly, there is genuine curiosity and respect for nature’s stories, far beyond the trophies or accolades. Looking ahead, visual media must evolve into immersive experiences – connecting audiences emotionally whilst educating them scientifically. With habitats shrinking and human pressures increasing, films can bridge the gap between science and society, motivating communities to act. The challenge is to balance beauty with urgency, ensuring conservation remains a shared responsibility.”

Bedi’s perspective highlights how visual media once carried the burden of introducing conservation itself to the public. From a time when wildlife films were dismissed as indulgent to an era of festivals, awards, and informed audiences, he underscores a crucial shift: recognition that conservation storytelling is not a luxury, but a necessity.

Why Wildlife Films Matter

Beyond nostalgia and technological progress lies a deeper question: why do wildlife films matter at all?

Dr. Anish Andheria, President Wildlife Conservation Trust and jury member at ALT EFF 2025, offers a compelling answer on why wildlife films are powerful and pathbreaking. Through his reflections on films showcased at ALT EFF, he illustrates how environmental cinema can weave together ecology, social justice, gender, displacement, and development, making complex issues accessible without oversimplifying them.

“It was past midnight at my home in Mumbai, and I was completely engrossed in the story of two young women. One sought to conserve the Himalaya using the snow leopard as a flagship, while the other fought to escape an early marriage. Both conservation and women’s empowerment are deeply complex issues, yet the film ‘The Snow Leopard Sisters’ – winner of ‘Best of Festival Feature Film’ at ALT EFF 2025 – beautifully highlighted the plight of the snow leopard alongside the struggle against patriarchy. The filmmaker creatively used the majesty of the Himalaya to give a voice to the women of Nepal and the ongoing tension between development and conservation.

As a jury member for ALT EFF 2025, I had the privilege of viewing some of the world’s best environmental films. From ‘Panah’, which documented a family’s heart wrenching eviction for a highway project, to ‘Would You Still Love Me if I Was a Sticky Frog?’, an unusual romantic film that explored the strain of a long-distance relationship between a researcher in Borneo and a professional in London, the quality was exceptional. Another masterpiece, ‘How Mallah Women Fought Caste Hierarchy and Sex Slavery,’ showcased the incredible resilience of fisherwomen in Bihar. Despite my three decades in conservation, I found these films both moving and motivating.

I firmly believe storytelling is an essential part of a conservationist’s toolkit. At the Wildlife Conservation Trust (WCT), our projects are built on years of rigorous ecological and social data. However, data alone is not enough; findings must be narrated effectively to resonate with policymakers, Forest Departments, and local communities. Contextualising research allows stakeholders to digest and act upon the information, and we have seen firsthand how storytelling catalyses action.

This is why WCT has an in-house communications team that works closely with researchers to create documentaries that translate science into compelling narratives. We are about to launch a 15-minute film made by a renowned filmmaker to demystify human-wildlife conflict, an issue WCT has addressed for over a decade. Our goal was to create a crisp, light-hearted, and cinematically professional film that remains relevant to multiple audiences without diluting the underlying science.”

For conservation organisations such as the Wildlife Conservation Trust, storytelling is not an add-on but a strategic tool. Scientific data may inform policy, but it is narrative that mobilises people. Films, when done responsibly, translate research into empathy and action, bridging the gap between science, governance, and communities.

Expanding Voices, Expanding Reach

If storytelling is central to conservation, then who tells the story and in what language becomes equally important.

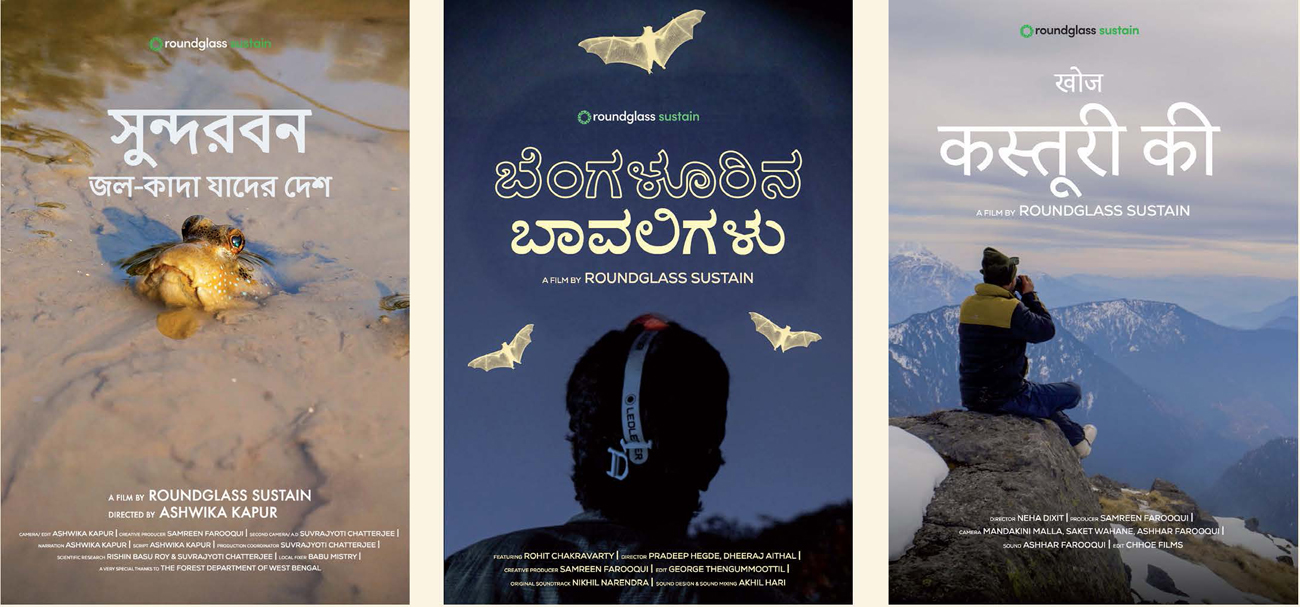

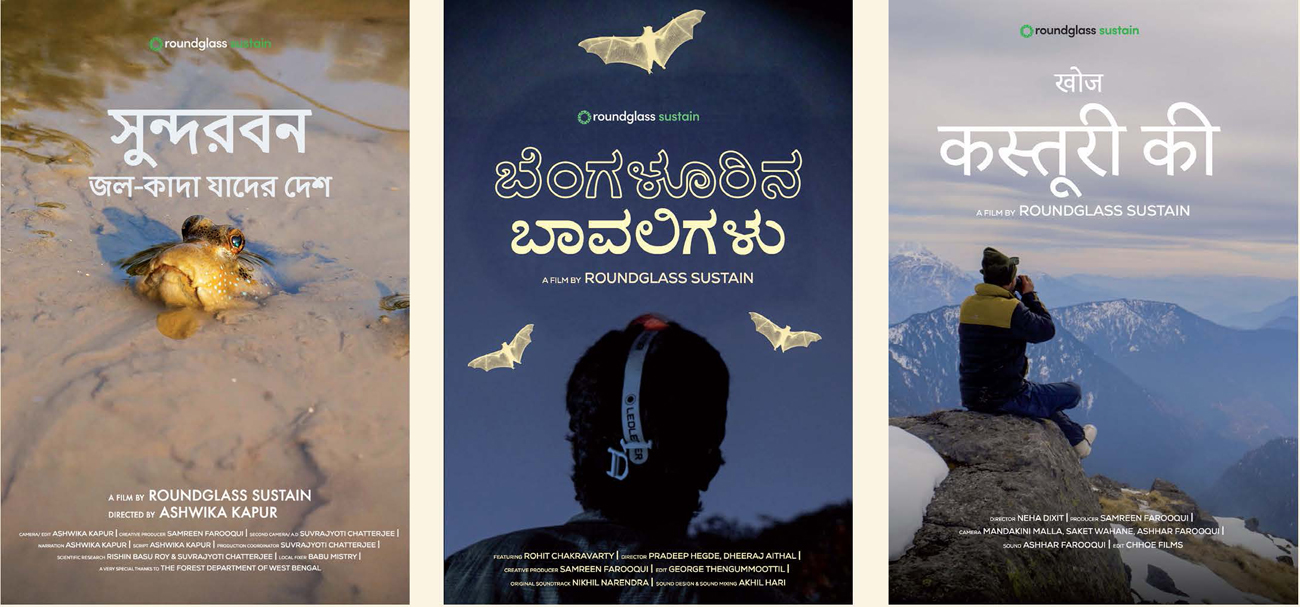

Samreen Farooqui, Head of Films at Roundglass Sustain, emphasises the transformative power of regional voices and linguistic inclusion.

She says, “Roundglass Sustain films create space for storytelling with a distinctly Indian voice. Stories that are inclusive, accessible and reimagine dominant narratives. We embrace a diversity of perspectives and do not shy away from the complexity inherent in India’s conservation realities. Thanks to our collaborations with filmmakers, sound artists, field researchers, conservation practitioners and local communities across India, we have released over 200 original short films that deepen public relationships with their natural world. But in a country as linguistically and culturally diverse as India, that relationship cannot be built in one language alone. Our work in translating and dubbing films into multiple regional languages is therefore not an add-on, it’s central to our philosophy. For me, the biggest win is that increasingly our films are being conceived and created in local languages, rather than being translated later from English.

When people watch their own stories in their own language, the film no longer feels distant, it becomes intimate and relevant. A Hindi or a local language film travels further, circulates longer and is shared widely within communities, schools and local networks. It allows conservation narratives to move beyond elite or urban audiences and reach those who are most closely connected to forests, rivers and biodiversity. For us, this is where real impact lies, in widening who gets to participate in environmental conversations and in ensuring that the voices of diverse communities are part of how we imagine and protect our natural world.”

Roundglass Sustain films create spaces for storytellers with distinctly Indian voices – to tell stories that are inclusive, accessible and reimagine dominant narratives. They embrace a diversity of perspectives and do not shy away from the complexity inherent in India’s conservation realities. Photo Courtesy: Roundglass Sustain.

Technology, Ethics, And The Road Ahead

As tools evolve, so do expectations. Award-winning filmmaker Kalyan Varma reflects on how technology continues to reshape both possibility and responsibility in wildlife filmmaking. He says, “Every few years, we use new technologies to tell wildlife stories. Pretty much every species and behaviour on Earth have been filmed before, and it is very hard to find new wildlife stories. This is where technology can help. You are able to show the animals and behaviours in a way which was not possible before. Two decades ago, films were shot in High Definition (HD) resolution. Over the years, we moved on to 4K resolution. Drones were born around the same time. We could show landscapes and animals from the air. The first generation of drones could only shoot landscapes as they had only a wide-angle lens; we had to go very close to shoot wildlife, which would disturb them. But in recent years, drones are being made with zoom features, and are able to film wildlife without disturbing them or sometimes, without them even knowing about it. The other important technological advancement has been equipment that allows filming in low-light or almost in no light conditions. Today, cameras can shoot in the light of a full moon, while thermal cameras (although the quality is still poor) can even see without any light. With these, we are able to showcase never-before-seen wildlife behaviour, which we could not do earlier. Wildlife filmmaking, more than any other forms, depends on advancement of technologies, and we must learn and adapt.

However, this progress only matters if it leads to better ethics, not just better images.

With newer technologies, we are also able to work quietly and less intrusively, a benefit for animals. Some, such as drones, are still an issue, and we have to regulate ourselves in not pushing them to the point where the animals and birds start fleeing because of their proximity. Thankfully, most Indian national parks do not willy-nilly allow drones, and we need special permissions to use them. Many people are apprehensive about camera traps, but they are in fact among the least intrusive ways to film wildlife.

Storytelling has evolved just as deeply as technology. For a long time, wildlife films relied on spectacles alone. Beautiful landscapes, rare animals, and dramatic hunts were expected to do all the emotional work. Today, that is no longer enough. If wildlife cinema is to matter beyond the screen, it must connect ecological stories to human lives. Most of us in the industry have been making films for western companies over the years. But with newer funding models, we are able to give an Indian gaze to our films, and also make films for Indian audiences. These are our films, shot by us and made for us.

Modern wildlife filmmaking also recognises that access is no longer limited to cinema halls and television slots. Streaming platforms, social media, mobile screens and regional language films have completely changed who gets to watch nature stories. A short film seen on a phone in a small town can sometimes do more for conservation awareness than a prime-time broadcast seen only by a niche audience.

This shift has encouraged filmmakers to think differently about form. Not every story needs to be 90 minutes long. Some ideas work best as 10-minute films, others as short social videos, and others still as immersive long-form documentaries. What matters is not the format, but whether the story reaches people in a way that feels honest and relevant.”

Rajesh Bedi also questions authenticity in an age of AI and digital manipulation arguing that no technology can replace patient fieldwork, ethical documentation, and lived experience in the wild. He says, “Ultimately the responsibility rests with the filmmaker. Genuine fieldwork and ethical documentation will remain irreplaceable. AI may assist, but it cannot substitute the patience, risk, and truth of witnessing nature in its raw form.”

From high-definition cameras to drones, thermal imaging, and low-light filming, technology has unlocked behaviours and perspectives once impossible to capture. Yet Varma is clear: progress must serve ethics, not just aesthetics.

ALT EFF

All Living Things Environmental Film Festival (ALT EFF) intentionally programmes films that push the traditional boundary on ‘wildlife’ or ‘climate’. We aim to showcase films that are entertaining and captivating, as much as they are educating. We believe this style of storytelling is the key to engaging new audiences that are outside of the silo of environmentalists and conservationists, which is, in turn, the key to building climate awareness at the scale needed to combat the issue.

For the first couple editions of ALT EFF, we found the international submissions to the programme to be consistently stronger. Each edition, we would have one breakout film from India, ‘All that Breathes’ for example, but rarely more. Now we are seeing the Indian shorts category as one of our toughest and most competitive! It is a brilliant evolution to watch.

Importantly, big names in the Bollywood industry are starting to get behind climate narratives, as we saw in our 2025 edition with Dia Mirza producing ‘Panha’, Zoya Akthar producing ‘Turtle Walker’ and Kiran Rao backing ‘Humans in the Loop’, which ultimately allowed it to get picked up by Netflix. Never before have we seen the weight of Bollywood thrown behind environmental cinema, and it’s very exciting.

This trend is not only in India; climate films internationally are increasingly human, increasingly creative and increasingly narrative-driven. Just last year in ALT EFF 2025, our Best of Festival Short film was awarded to ‘Would You Still Love Me if I Was a Sticky Frog’? This film, essentially a rom-com, depicts a long-distance phone conversation between a couple and splices in comparisons to rainforest-dwelling endangered species. It’s a film that Jury member Amoghavarsha said “breaks every model we’ve seen before on conservation films”.

Time will tell what creative directions environmental films take, but one thing is for sure, ALT EFF will keep programming them and showcasing them to as wide of audiences as possible, with the key goal being to engage new audiences (who are not yet ‘environmentally-inclined’), and allowing the films to do the talking.

Laura Christie is the producer and co-founder of the All Living Things Environmental Film Festival (ALT EFF), India’s premiere showcase of today’s climate stories.

The Future Of Wildlife Films

Sanctuary’s inhouse natural history and photography consultant Saurabh Sawant has worked on a wide range of film projects. He feels that while wildlife films have long inspired wonder and connection, their future impact in India depends on more responsible, ethical, and collaborative storytelling that helps society consciously decide what is worth saving in an age of ecological crisis, misinformation, and human-nature entanglement. He says, “Almost every filmmaker writing in this story, every naturalist, and every wildlife enthusiast has been influenced in one way or another by early wildlife films, their charisma, grandeur and excitement. For many, it began as romance: the pull of exotic biodiversity and the thrill of a world that felt distant and wild. Even today, visuals and sound remain among the most powerful ways to experience nature. In many ways, this is what has fuelled the exponential growth of social media as a medium. And yes, as much as we may want to curse TikTok and Instagram reels, we all end up indulging in them for the same reason. These platforms are tools. They can amplify nonsense, or they can carry more meaningful narratives. Wildlife films have therefore been important, even if we cannot always prove that they directly changed policy or delivered measurable conservation outcomes. Perhaps the next step is to document this better: which stories actually shifted decisions, changed public pressure, or strengthened protection on the ground? Some of this impact is already visible in how conservation organisations use films today. The Sanctuary Nature Foundation is already using strong wildlife films and visual storytelling, often through collaborators and partners, to influence young minds through its wide-reaching conservation programmes. When a child sees a forest as alive and worth defending, conservation stops being a ‘topic’ and becomes a relationship.

Throughout history the camera has helped bring distant forests into our homes and imaginations. But today, the distance is no longer just geographical. It is emotional, political and ecological. Climate change is altering habitats faster than our stories can keep up. Human-wildlife conflict is rising at the edges of Protected Areas. Rivers are being fragmented, grasslands are still being dismissed as “wastelands”, and species are disappearing quietly, without ever becoming a headline. The style of filmmaking has changed too, and much of that shift is welcome, but the noise has also increased. In this reality, the most meaningful wildlife films of the future will not simply show what is wild. They will help society decide what is worth saving.

What comes next, therefore, is not only a technological upgrade. It is a narrative one. Indian wildlife filmmaking is entering a phase where wonder must still exist, because wonder is how care begins, but where responsibility must sit at the centre of storytelling. Not every film needs to be a manifesto. Yet, every film carries consequences: what it amplifies, what it simplifies, what it leaves out, and who it makes visible. Technology will inevitably shape the next decade of this genre. Artificial Intelligence is already transforming how stories are researched, edited, translated and distributed. Used well, AI can reduce barriers for emerging filmmakers by speeding up transcripts, simplifying subtitling into Indian languages, searching archives efficiently, and supporting small teams with heavy post-production demands. But the same tools also raise an urgent question of trust. When images can be altered or generated with ease, the future of wildlife films will depend on ethical clarity: transparency about reconstructions, restraint in manipulation, and an honest distinction between cinematic enhancement and ecological truth. In conservation, credibility is not a stylistic choice. It is the foundation on which public belief is built. This matters even more because social media is already flooded with AI-generated clips that shape wildlife perception in unpredictable ways, especially around conflict. Some are bizarrely entertaining: a tiger ‘picks up’ a man from his porch, and the next clip shows the tiger bringing him back and placing him neatly in his chair, as if correcting a prank. It’s funny, but it’s also complicated. In a country like India, where the relationship with wildlife is emotionally charged and physically real, such content can quietly shape fear, hostility, or false confidence. Good storytelling now has to resist not only misinformation, but virality.

Through The Lens Of Care: Our Film Journey

When speed became the default language of our time, The Habitats Trust (THT) responded differently: by slowing down, watching closely, and letting films grow out of patience.

Our film journey has never been about spectacle or sensationalism. It has been about presence, and standing still long enough for ecosystems, species, and landscapes to reveal themselves without distortion.

We did not begin making films to impress or persuade, but because there were stories around us that were quiet, intricate and vulnerable, and that were not being seen. Our filmmaking emerged organically from time spent in the field: long hours of watching, listening, and learning how life unfolds when no one is trying to frame it for effect.

Over the years, this film journey has become an extension of our conservation work. Each film grows out of a specific landscape – a wetland breathing through the seasons, a grassland dismissed as empty, a forest sheltering species that survive without names or headlines. What unfolds on screen is never just biodiversity. It is the relationship between species and habitat, people and land, patience and understanding. We document not only natural history, but also the journeys of champions such as scientists, conservationists, filmmakers, community custodians, and on-ground practitioners whose work sustains these landscapes. Many of our films carry nuanced layers of culture, biodiversity, and stewardship, recognising that conservation is as much about people as it is about species.

As our films travelled beyond the field, something meaningful happened. They found their way into classrooms, community screenings, festivals, and conversations, where conservation is often discussed but rarely felt. Our audience encountered species they had never known and habitats they had never thought to value. We witnessed curiosity replace indifference, and attention replace assumption. Over time, this work has been recognised across national and international platforms, affirming the collective efforts of our filmmakers, directors, editors, cinematographers, and collaborators, each of whom has played a vital role in shaping these stories and deserve due credit.

In a world where biodiversity loss is accelerating faster than our collective attention, choosing to focus on lesser-known species feels essential. Conservation narratives often revolve around the iconic species and urgent debates. Yet what sustains ecosystems most often escapes the camera’s gaze. Small mammals, insects, amphibians, birds, grasses, and soil persist quietly while doing the work of balance. By attending to these lives, we hope to gently rethink what matters.

Foregrounding lesser-known species is especially vital today. Conservation storytelling has long been dominated by a handful of charismatic animals, while entire ecosystems and the species that sustain them remain invisible. By focusing on the overlooked, we quietly challenge this hierarchy of value. The message is subtle yet radical – survival is not reserved for the spectacular. Every species, however small or unnamed, holds ecological consequences.

We believe filmmaking is a form of stewardship. What we choose to document today becomes memory tomorrow, and memory shapes responsibility. Our films go beyond documentation; they are used as tools for policy advocacy, dialogue, and on-ground action, helping bridge the gap between field realities and decision-making spaces. In bearing witness to the fragile, the ordinary, and the unseen, our films seek to leave behind more than images. They aim to nurture empathy, humility, and hope.

What we choose to film, how we frame it, and whose stories we amplify ultimately shape what societies decide is worth saving. In that sense, these films are more than visual records. They hold memory with care, speak to audiences ranging from local communities to policymakers and decision-makers, and in doing so, suggest a gentler way of living together.

Kanak Angirish is Lead for Communications and Branding at THT. An author and strategist, her work spans public affairs, communications, and brand leadership. She holds a Master’s in English Literature and an Honours degree in English from the University of Delhi.

At the same time, a quieter contradiction is becoming impossible to ignore: the footprint of production itself. Large crews, repeated recces, long-distance travel and high-resource shoots can sit uncomfortably beside the habitats we claim to protect. The future may demand leaner and smarter methods, including smaller crews, local hiring, longer stays instead of repeated visits, and filmmaking models that treat landscapes with the same respect the camera seeks to portray. We also need stronger research into impact beyond viewership and box office, so massive-budget productions can be justified more honestly, or redesigned more responsibly.

Wildlife documentary posters by The Habitats Trust (THT), an organisation that believes in filmmaking as a powerful form of communication. THT uses film as a tool for policy advocacy, dialogue, and on-ground action, thus helping bridge the gap between field realities and decision-making. Photo Courtesy: The Habitats Trust.

Perhaps the biggest shift ahead will be collaboration. The most urgent conservation challenges in India are no longer single-species stories neatly contained within Protected Areas. They are complex, lived, and shaped by law, livelihood and land-use change. Films that matter most will increasingly be co-designed: scientists ensuring accuracy, Forest Departments offering context and legitimacy, NGOs bringing community linkages, and filmmakers shaping narrative craft. The result is not a film that becomes ‘technical’, but one that becomes trustworthy, cinematic storytelling built on lived truth. Even films on human-wildlife conflict can evolve beyond ‘problem animal’ narratives to stories of shared adaptation, coexistence and practical solutions. Here, research has to be deep. Ecology and behaviour are not optional details, because films shape public attitudes at scale. This is also where emerging technology becomes exciting, not just for polish, but for possibility. With strong scientific grounding, even limited documentation can become stunning visual storytelling. Big productions have shown how stories of evolution and prehistoric animals can engage massive audiences and still make them care about biodiversity today. Rare behaviours and unseen species can be shown through high-accuracy VFX, guided by scientific collaboration, with minimal disturbance on ground. Add immersive formats such as 3D, interactive experiences, and classroom-ready storytelling, and audiences can feel closer to wildlife than ever before.

Another important frontier is what we choose to call ‘wildlife’. India’s conservation future will be decided as much in farms, wetlands, coasts and grasslands as in tiger reserves. The next generation of filmmakers can broaden the frame: pollinators, amphibians, freshwater systems, soil biodiversity, invasive species, native grasslands and mangroves. New camera systems and filming tools will also keep revealing never-seen-before angles, behaviours and perspectives, and often at a faster pace than ever before. In an age of climate disruption, the most powerful films will help audiences see ecosystems not as scenery, but as infrastructure for survival. Regional filmmaking will be central to this shift, not just through language, but through worldview. Empowering regional storytellers must mean more than dubbing later. It means mentorship, fair access, safer permits, and sustained support where the story originates. For this impact to be truly felt on ground, the exclusivity around equipment, funding and access has to break.

The Impact Of Films

Films are without a doubt the most powerful tools, agents for change and transformation. Long before conservation became a commonly used word, visual storytelling helped people see, feel, and understand the fragile relationship between humans and nature.

Series such as ‘Earth Matters’ (a wildlife and environmental show that I created) that began airing in the late 90s and continued to reach people decades later, went beyond documentation and became catalysts for awareness, policy change, and shifts in public consciousness, impacting everyone from policymakers to grassroots communities.

When ‘Earth Matters’ first aired in 1999 on DD National, conservation was still on the margins. The series reached over 800 million viewers, inspired village-level action, and quietly shaped two generations. Even today, people across the country tell me they grew up watching it and found their values shaped by it. One young woman from Odisha once said, “Main ‘Earth Matters’ banungi (I will be ‘Earth Matters’).” She went on to study environmental science and later came to thank us for giving her direction in life.

Over the years, many of our films and of those by other filmmakers have directly influenced conservation outcomes. These films remind us that laws become meaningful only when stories carry them into people’s hearts and everyday lives.

Today, our planet faces unprecedented pressures from climate change to unchecked consumerism. In a world of shrinking attention spans and rapid technological change, storytelling must evolve, but its purpose remains the same: to reconnect people to the living world.

Forums such as greenstories, which we launched recently, are vital in this moment – supporting more voices from this part of the world, refining narratives, and offering our own deeply rooted perspectives to a global audience. Films remain our most powerful way to reach millions, inspire collective responsibility, and remind us that this planet is our only home – and still worth fighting for.

Mike H. Pandey is a globally renowned wildlife conservationist, filmmaker, educator, and communicator. He recently won the Jackson Wild’s Highest Honour – the 2024 Legacy Award, and has been a three-time Green Oscar winner. His films have led to five legislative changes in India, including the protection of whale sharks globally, vultures, horseshoe crabs, and elephants.

Finally, the future of wildlife films in India must bring communities from the margins of the frame to the centre of the process. People living closest to forests, rivers and coasts are often the first witnesses to ecological change. Their knowledge is frontline evidence. Films can create pathways to train local youth as camera assistants, field researchers, sound recordists, guides and co-producers, building dignified livelihoods linked to keeping nature alive. Citizen science can strengthen this ecosystem further. Wildlife films can invite audiences not only to watch but to act: document seasonal changes, track species, report threats, and support institutions that protect habitats. The most impactful films of the future will not end with inspiration alone. They will leave behind more engagement. In the end, the question is no longer whether wildlife films can move people. They already do. The question now is whether they can help society choose wiser futures, where conservation is not a luxury, but a shared commitment to life, livelihoods and landscapes.”

Kalyan Varma perched atop his jeep to get a viable angle while filming elephants in the tall grass of the Manas National Park. In his words, “Storytelling has evolved just as deeply as technology. For a long time, wildlife films relied on spectacles alone. Beautiful landscapes, rare animals, and dramatic hunts were expected to do all the emotional work. Today, that is no longer enough. If wildlife cinema is to be effective beyond the screen, it must connect ecological stories to human lives.” Photo Courtesy: Kalyan Varma.

Why Stories Matter!

Wildlife films can certainly help conservation in India, but only when they move beyond spectacle and engage honestly with complexity. India is one of the most biodiverse countries in the world, yet that diversity exists within landscapes under immense human pressure. Habitat loss remains one of the greatest threats, and as habitats shrink and fragment, conflict between people and wildlife becomes the space where conservation ultimately succeeds or fails.

This is where storytelling comes in. In a country like India, where conservation is deeply tied to livelihoods and coexistence, storytelling becomes a bridge – it transcends barriers, influences perspectives, and makes a long term impact. People protect what they connect with emotionally. Data alone doesn’t move people; stories and visuals do. Films allow us to make the unseen visible – to give faces and narratives to species and landscapes that would otherwise remain abstract ideas.

Historically, wildlife films were largely observational, documenting nature as something distant and untouched. Over time, both globally and in India, the medium evolved. Especially post-Independence, there was a gradual shift. Wildlife was no longer just meant to be admired from afar, but something deeply entangled with people, history, and politics. The camera moved from being a tool of record to a tool of responsibility. Globally too, this shift mirrored changing values – from showcasing untouched wilderness to acknowledging that very little wilderness exists without human influence. Modern conservation films no longer pretend humans aren’t part of the frame. Films began asking harder questions: Who shares this landscape? Who pays the cost of conservation? What happens when habitats shrink and boundaries blur?

One of the earliest and most powerful shifts in India came when films began influencing real-world outcomes. ‘Shores of Silence’, which documented the whale shark fishery in Gujarat, is a landmark example. It didn’t just show an animal; it told a story of culture, livelihoods, and the cost of exploitation. That film contributed directly to legal protection for the species. ‘Sahyadris: Mountains of the Monsoon’ (2008), my first film, introduced the mountain jungles of the Western Ghats to a global audience. Recognised as one of the world’s most significant biodiversity hotspots, the Western Ghats were designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2012, a process supported in part by the visibility created through such films. These moments demonstrate the potential of wildlife storytelling to influence policy and practice – not through outrage, but through understanding.

Yet impact cannot be measured only through legislation. The deeper value of wildlife films lies in connection. People cannot care about what they don’t see, and they will not protect what they don’t emotionally understand. In a country where many species live outside Protected Areas – in tea gardens, farmlands, and village edges – storytelling helps reframe conservation not as exclusion, but as shared responsibility.

The most effective wildlife films in India today are no longer just about admiration. They are about ethics, coexistence, and accountability. They shine a light on invisible species, overlooked ecosystems, and human-made landscapes, where wildlife persists against the odds. They ask difficult questions: How do animals adapt to human-made environments? What does coexistence really look like? And who bears the cost of conservation?

For me, wildlife filmmaking sits at the intersection of science and storytelling. The goal is not just to inform, but to create emotional entry points into scientific realities. A successful film leaves viewers with a sense of wonder – and responsibility. It’s about making people feel awe, but also discomfort, because both are necessary. If a film can make someone pause, reflect, and see themselves as part of the ecosystem rather than separate from it, then it has done its job.

So, are wildlife films helping conservation in India? I believe the impact of storytelling can last a lifetime – even generations. When films are honest, ethical, and rooted in real landscapes, they don’t offer easy answers. Instead, they start essential conversations, reminding us that nature is not separate from us. We are part of the story, and the future depends on how we choose to tell it.

Sandesh Kadur is an Indian wildlife filmmaker, conservation photographer and National Geographic Explorer known for award-winning natural history films and visual storytelling.

Beyond The Screen

Indian wildlife filmmaking today stands at a critical juncture. It is more visible, more technologically advanced, and more accessible than ever before. Yet its true measure lies not in awards or visuals, but in impact on attitudes, policies, and the fragile relationship between people and nature.

As these voices collectively reveal, wildlife films are no longer just about showing the wild. They are about asking difficult questions, amplifying unheard voices, and reminding us that conservation is not a distant cause, it is a shared responsibility, unfolding both on screen and in the wild.